Earth:McClure Arctic Expedition

The McClure Arctic Expedition of 1850, among numerous British search efforts to determine the fate of the Franklin's lost expedition, is distinguished as the voyage during which Robert McClure became the first person to confirm and transit the Northwest Passage by a combination of sea travel and sledging. McClure and his crew spent three years locked in the pack ice aboard HMS Investigator before abandoning it and making their escape across the ice.[1] Rescued by HMS Resolute, which was itself later lost to the ice, McClure returned to England in 1854, where he was knighted and rewarded for completing the passage.

Preparation

Lady Jane Franklin pressed the search for the Franklin Expedition, missing since 1847, into a national priority. McClure had served as first lieutenant of HMS Enterprise under James Clark Ross in 1848, which returned in 1849 without discovering a trace of the lost explorer. Faced with a continuing lack of progress, the British Admiralty on 15 January 1850 ordered a new expedition to "obtain intelligence, and to render assistance to Sir John Franklin and his companions, and not for the purposes of geographical or scientific research," although a completion of the proposed Northwest Passage from the opposite direction would not be without merit.[2]

Two ships were assigned to this task. The Enterprise was returned to the search under Captain Richard Collinson, and the Investigator under Commander Robert J. McClure in his first Arctic command.[3] Extensive repairs were required for both ships, which had already weathered Arctic service, including the installation of a modern Sylvester's Heating Apparatus. The Investigator, her figurehead representing a walrus, had been fitted with a 10-horsepower locomotive engine and strengthened extensively in 1848.[4]

Preserved meat was secured from Gamble of Cork, Ireland, and although some spoilage was experienced, it had no major impact on the voyage (subsequently discovered to be the case with Franklin[5]).

Double rations of preserved limes were provisioned to offset scurvy. A seven-month voyage across the Atlantic, through the Straits of Magellan, to Hawaii and through the Aleutian Islands to the Bering Strait was planned to reach the pack ice during the most ice-free Arctic season. The ships were provisioned for a 3-year voyage.

The initial voyage

On 10 January 1850 the rapidly prepared ships set out from Woolwich, England, then completing the loading of supplies in Plymouth on the 20th. The crew numbered 66, including German clergyman John Miertsching, who served as Inuit interpreter.[6] By 5 March they had crossed the equator southward and slave ships were observed in the latitude of Rio de Janeiro,[1] described by the expedition surgeon Alexander Armstrong as 'suspicious.' Their southernmost extent, the Strait of Magellan, was obtained on 15 March, the Enterprise always well ahead of the slower Investigator. The two ships lost direct contact after the strait was completed, although McClure reported (by bottle-message) that he considered their company formally parted on 1 February 1850.[7]

Continuing north through several storms, nearly 1000 lbs of stored biscuit was ruined by water leakage,[8] but was later offset by fresh supplies from the Sandwich Islands. On 15 June the Investigator re-crossed the equator amid clear skies and tropical birds, already having journeyed nearly 15,000 miles. Spirits ran high, with McClure noting of the crew in his journal, "I have much confidence in them. With such a spirit what may not be expected, even if difficulties should arise?"[9] On 1 July they made port at Honolulu, taking on fresh provisions, and having missed the Enterprise by only one day. Five days later McClure set out heading north-west, and aided by prevailing winds made the Arctic Circle on 28 July bypassing his consort ship and HMS Herald. The crew busied themselves by readying the arctic gear as they prepared to explore the Arctic alone.

The Arctic reached

Rather than waiting to rendezvous with the Enterprise, the unusual decision was made to take the Investigator alone into the ice near Cape Lisburne. On 20 July McClure had sent a letter (via the Herald) notifying the Secretary of the Admiralty of this intent, stating that since the Enterprise had already detached from the expedition, proceeding on alone was the best contingency plan available to insure the success of their mission.[10] The ice fields were sighted on 2 August at 72°1′ north. Unable to find open leads, they rounded Point Barrow and entered unexplored waters[1] and the first ice floes.

Meanwhile, the Enterprise, arriving at Point Barrow about a fortnight later than the Investigator, found its passage blocked by ice and had to turn back and winter in Hong Kong, losing an entire season before returning again the following year, this time successfully. The two ships never made contact for the remainder of their journeys, and the Enterprise carried out its own separate Arctic explorations.

On 8 August McClure and the Investigator made contact with local Inuit, who offered no news of Franklin, and were unaccustomed to seeing sailing ships. Making their way along the coast east of Point Barrow,[11] message cairns were left at the site of each landing, crews occasionally trading with local Inuit but obtaining no news of Franklin. The progress north-west was frustrated by ice and shoals, and at one time the Investigator became grounded so firmly that all stores had to be unloaded to her boats (one of which capsized, losing 3344 lbs of dried beef) before she could be freed. Alternating between pressing ice floes, then open water, McClure's continued to advance to the north-east, reaching the solid pack ice on August 19.[12]

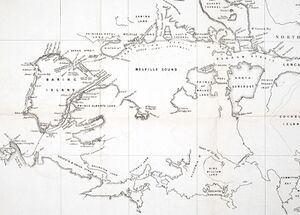

Contact was made with several groups of local Inuit near Point Warren near the Mackenzie River, one of which reported the death of a European.[13] It was soon determined not to be a member of Franklin's party, but that of an overland expedition of Sir John Richardson two years earlier. The ice to the north remained impenetrable, but they made Franklin Bay to the west by 3 September amid much wildlife in air and sea. After sighting an extent of Banks Island, claiming it as "Baring Land",[14] a brief land exploration was made, presumably the first.[15] A rock formation at a prominent cape was named Nelson Head on 7 September after its imagined resemblance to Lord Nelson. The coast was followed in hopes of access to the north.

Periods of good progress were made, until a wind change caused the ice to close in around the Investigator on 10 September just as they had discovered a route of some promise, the Prince of Wales Strait.[3] Their progress through the ice was deliberate and slow, aided at times by the use of ice anchors and saws. Daily temperatures were now around 10 °F. By the 16th, they had reached 73°10′ N, 117°10′ W, logged as her most advanced position.[16] Just short of Barrow's Strait, the rudder was unshipped and winter preparations were begun. A year's worth of provisions were brought on deck in anticipation of the ship being crushed by the pack ice. The dangerously drifting pack finally ground to a halt on 23 September.

At times violently shifted by the grinding pack ice, the Investigator endured just south of Princess Royal Island, the pack becoming less violent by 27 September 1850. On the last day of September, the temperature fell below zero for the first time, as the top-gallant masts were taken down for the winter and the last birds were observed. Periods of calm were often punctuated by violent ice movement. McClure noted "The crushing, creaking, and straining are beyond description, and the officer of the watch, when speaking to me, is obliged to put his mouth close to my ear, on account of the deafening noise."[17] The ship was lifted several feet, and black powder was used to blast any nearby hummocks that threatened.

Several explorations across the ice to land were made, and observations left McClure with no doubt as to the existence of a Northwest Passage.[1][18] In mid-October, formal possession of Prince Albert's Land and several nearby islands was taken. The crew began the routines that would characterise their Winter Quarters, which included lessons in reading, writing, and arithmetic. Hunting opportunities were sparse, although five musk oxen were taken around this time, extending rations (some lost to spoilage) with fresh meat.

The Northwest Passage

On 21 October Captain McClure embarked on a seven-man sledge trip north-east to confirm his observations of a Northwest Passage. McClure provided that confirmation upon his return on the 31st, having seen an unblocked strait to the distant Melville Island from a 600-foot peak (180 m) on Banks Island. The entry placed in the ship's log read:

"October 31st, the Captain returned at 8.30. A.M., and at 11.30. A.M., the remainder of the parting, having, upon the 26th instant, ascertained that the waters we are now in communicate with those of Barrow Strait, the north-eastern limit being in latitude 73°31′, N. longitude 114°39′, W. thus establishing the existence of a NORTH-WEST PASSAGE between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans." [19]

The first winter and summer

The sun departed on 11 November with temperatures averaging −10 °F with the below-deck temperature of 48 °F, the crew in good health. Below deck air quality was maintained by increased ventilation and regular airing out of the quarters.[20] 1851 was welcomed in as the crew amused themselves, occasionally catching foxes or spotting seals. Winter temperatures averaging −37 °F, and on 3 February the sun returned after 83 days of darkness. An emergency depot of provisions and a whaleboat were made on the nearby island. Reindeer, Arctic fox, hare, raven, wolf and a polar bear were observed as local expeditions resumed.

As spring returned, the decks of the Investigator were cleared of snow and repairs begun. Additional local expeditions were mounted, but none with the object of attempting to meet with concurrent regional rescue expeditions; the Resolute under Captain Horatio Austin, believed to be near Melville Island, the Assistance under Captain Erasmus Ommanney, the Pioneer under Lt. John B. Cator, and the Intrepid under Sherard Osborn as well as more distant ships under Captain William Penney, Admiral Sir John Ross, the expedition under Lt. Edwin De Haven and the overland expedition of John Rae.[21][22] By mid-May, additional hunting and exploration parties were sent out to supplement the provisions as temperatures rose above zero, some returning with frostbitten invalids, one having met an isolated group of Inuit seal hunters. One party went around Banks Island and showed that it was an island. Another party was on the south shore of Victoria Island at about the same time that John Rae (explorer) passed 40 miles to the south. No traces of Franklin were found. As summer returned, the seven-foot thick ice showed signs of diminishing, the surfaces pooling with water. An early break up was anticipated.

Preparations were made for the ship's anticipated release from the ice. Late June temperatures reached a high of 53 °F, but the ice maintained its hold on the Investigator until it was released on 14 July, soon under sail amid the grinding floe near the Princess Royal Islands. Progress northward was made, the ship often attached to larger floes, and there was even some anticipation of completing the passage in that direction. However, with August this progress slowed to a crawl as the ice offered few chances to advance through the solid northerly ice. On 14 August they attained their northern-most position at 73°14′19″ N, 115°32′30″ W in the Prince of Wales Strait. It was later suggested that, if the Investigator had been equipped with a screw propeller, she could have pressed the 45 miles to Melville Island, completed the Northwest Passage, and returned to the United Kingdom in that same year.[23]

The decision to abandon the strait and proceed around the south coast of Baring Island[24] (his name for Banks Island) led them to open water and a wider area of search. Rounding to the north east, they continued through the loose ice until conditions compelled them to secure the ship to an iceberg for protection. Explorations of the nearby coast were made, revealing abandoned Inuit camps and the unusual discovery of petrified wood from an extensive forest at 74°27′ N. As winter showed signs of return, they were threatened by the ice several times while still attached to their iceberg. These events were successfully managed by the crew, often by blasting the ice, but McClure chose not to set off from the iceberg for nearby open water, passing several opportunities to do so.

The second winter and summer in Mercy Bay

Subsequent efforts to move the ship further eastward made slow progress, but occasional stretches of open water contributed to their progress towards Melville Island. Rather than following the pack ice east, McClure chose to take refuge in an open bay. On 23 September the ice made an end to their progress, as the ship was made ready for a second winter – entering the bay they now occupied was the seen by some of the crew as a dire mistake. Ship's surgeon Armstrong went so far as to state "Entering this bay was the fatal error of our voyage."[25] The pack ice would have taken them within 50 miles of Melville Island, and improved their chance of an early break-up in the spring. The location of their wintering was 74°6′ N. 118°55′ W., and was subsequently named Mercy Bay.

Diminishing provisions, as well as the subsequent caching of food at the Princess Royal Islands left them with fewer than ideal stores. By October, heating was briefly curtailed until the more severe periods of winter, with temperatures below deck holding near −10 °F. Hunting parties were generally successful, although their exploration frustratingly revealed extents of open water that would have provided escape, only 8 miles outside of Mercy Bay. As winter pressed on, the weakening hunting parties frequently required rescue. On 10 November the final 'housing in' of the ship commenced, largely sealing it for the winter. The crew busied themselves in the manufacture of needed items, and adopted patches of gun wadding as their currency. Tedium was severe, with two crewmen briefly going mad with boredom.[3] In December, storms rose up as temperatures continued to fall.

1852 began with the crew generally healthy, maintained largely by the reindeer venison provided by the hunters, temperatures reaching −51 °F. Frequent hunting of nearby reindeer continued to supplement the provisions, although the hunters suffered from the cold and occasionally required rescue. Despite the occasional fresh meat, the crew continued to gradually weaken. Of all the ships searching for Franklin the previous year, now only Enterprise and Investigator, separated, remained in the arctic.[26]

On 11 April Captain McClure led seven men out by sledge with 28 days of provisions to reach Melville Island across the ice, and hopefully to make contact with other British explorers in the area. In late April the first case of scurvy was observed, with several others soon to follow. McClure's party returned on 7 May, relating that poor visibility and soft snow had hampered their progress. They did not reach Melville Island, but obtained enough of a view of the straight and large harbor to determine that Captain Austin's forces were not present. They did, however, find the cairn left by Sir Edward Parry during his 1819–20 expedition, which also contained a June 1851 communication from Captain Austin. This did not, however, include the information that traces of Franklin's expedition had been found the previous year at Beechey Island.

June found the crews preparing for their expected liberation from the ice of Mercy Bay, and although temperatures rose, it was cooler than the previous year. Cases of scurvy continued to increase,[27] although hunting and gathering of the emerging sorrel provided improvement. By mid-month, the ice outside the bay was already in motion, showing some open water by the 31st. The bay ice remained fixed. By September all hopes of freeing the ship had evaporated, and McClure planned for the possibility of abandoning the ship in the spring, writing that "nothing but the most urgent necessity will induce me to take such a step." [28]

The third winter

On 8 September McClure announced his plan for springtime escape, in which 26 of the crew would make for Cape Spencer (550 miles away), where Austin had left a cache and a boat, and from there, to seek rescue on Baffin Bay. A smaller party of 8 men would proceed back along the shore of Banks Land, to the cache and boat set by McClure in 1851, then making for the Hudson's Bay Company's post on the Mackenzie River for rescue. This would stretch the provisions for the crews remaining on board the Investigator. To this end, food rations were immediately reduced, and hunting success became ever more critical, which now included mice.

With October, the health of the crew continued to decline, the coming winter the coldest yet. The ship was prepared for winter as temperatures below deck were below freezing. Full darkness returned on 7 November. Morale and physical activity, including hunting, waned. The officers continued hunting, often requiring rescue as temperatures reached −65 °F. 1852 ended with the crew weaker and more afflicted than ever before, although not a single member of the crew had been lost.

1853 brought the coldest conditions yet, once reaching −67 °F. The crew passed the days with minimal activity, working on small projects of necessity and hunting when possible, since McClure had prepared no diversions for his crew.[3] Rations were thin and the sick bay was full, even minor illnesses bringing exaggerated disability to the weakened crew. McClure continued preparing for his spring escape parties, planning to send the weaker able men in order to improve the long-term chances of those left behind.[1][29] Crew selections were made and announced on 3 March, to the disappointment of those to be left behind. Full rations were restored to those men preparing to set out in mid-April, and their health improved. Still, on 5 April, the first crew member, John Boyle, succumbed to illness, which impacted morale and underscored the dire nature of their situation.

Relief and the fourth winter

Preparations for the escape parties continued, despite their slim chances for success. On 6 April a detail of men digging Boyle's grave observed a figure approaching from seaward. It was Lieutenant Bedford Pim of H.M.S. Resolute, which was wintering off Melville Island under Captain Henry Kellett 28 days away by sledge. The Resolute was accompanied by the Intrepid, laying supply depots off Melville Island for the continued search of Franklin and now McClure[30] (having located one of McClure's stashed messages from 1852). Afterwards, Pim described meeting McClure:

"Who are you, and where (did) you come from?"

"Lieutenant Pim, Herald, Capt. Kellett." This was more inexplicable to M'Clure, as I was the last person he shook hands with in Behring's Straits.[31]

Two days later, Pim left for the Resolute, about 80 miles east, followed soon by McClure and six men, who would journey for 16 days.

Despite the encouraging news of relief, conditions aboard the Investigator were still deteriorating. Scurvy advanced with the reduced rations, and on 11 April another crewman died, and another on the following day. Some exercise was possible for the crew, breathing aided by the modern Jeffreys respirator.

On 15 April the 28-man traveling party, now concentrated on Melville Island alone, set out on three sledges. Four days later, McClure reached the ships and met with Captain Kellett and Commander McClintock.[32] McClure returned on 19 May, with the surgeon of the Resolute, Dr. W.T. Domville. A medical survey was made to determine whether the Investigator could be adequately manned if freed from the ice. The assessment fell short of the requirements, "utterly unfit to undergo the rigour of another winter in this climate,"[33] making the abandonment of the Investigator inevitable, ordered by Captain Kellett of the Resolute.[3] The official announcement was made, and all men were put back on full rations for the first time in 20 months. A beach supply depot was established by the end of May, accompanied by a cairn and a monument to the fallen crew members.

On 3 June final flags were raised and the remaining crew abandoned the Investigator, travelling by sledge to the Resolute, with 18 days of provisions and McClure leading the way on foot. Progress across the thawing pack ice was slow, as the four sledges weighed between 1,200 and 1,400 lbs. The weakened crew made Melville Island on 12 June and reached the ships on the 17th.

A party of invalids had been taken from the Resolute to Beechey Island and the North Star to be returned to England in October 1853, along with the first news of the Investigator and the Northwest Passage to the outside world. Hunting supplemented the provisions while the Resolute and Intrepid waited for their own release from the ice. The breakup came on 18 August and the ships followed the edge of the pack ice before becoming fixed in the ice in early November at 70°41′ N, 101°22′ W. The combined crews prepared for another winter in the ice, while another crewman died on the 16th. Far from shore, no effective hunting could be resumed. With 1854 began the fifth year of Arctic service for the crew of the Investigator.

Escape and return

Plans were made to detach the crew of the Investigator to the North Star at Beechey Island in the spring of 1854. These three sledge parties set out on 10–12 April. The journey was severe, but the crews were in improved condition. Socks routinely froze to feet and had to be cut off to fight frostbite. Despite these unfavourable circumstances, the North Star was reached on 23–27 April by the parties. Even with this relief, another man succumbed at Beechey Island. They occupied themselves searching the surrounding area for additional traces of Franklin, as Beechey Island was now known to be his first winter quarters. Meanwhile, the Resolute and Intrepid were themselves abandoned,[34] with their crews joining the Beechey Island camp on 28 May.

An exploration party by the Resolute had earlier made contact with Captain Collinson and the Enterprise and learned of their own path of search. A report on the condition of the Investigator, now abandoned some 12 months, was also obtained and indicated that she was tattered, leaking but otherwise intact and held by the ice – Mercy Bay was still solid. By mid-August, the North Star was herself released from the ice, although two other nearby ships (Assistance and her tender Pioneer) were abandoned on the 25th. They proceeded along Greenland and reached the English port of Ramsgate on 6 October 1854, having been gone four years and ten months and losing five men.

Aftermath and controversy

Upon return to England, McClure was immediately court martialled and pardoned for the loss of the Investigator, according to custom. He was awarded a share of the £10,000 prize for completing a Northwest Passage, knighted and decorated.[35] He never made another Arctic voyage.

Despite this overall success, several points of controversy were raised:

- When the ambitious McClure severed contact with their consort ship Enterprise before reaching Arctic waters, he essentially initiated a solo voyage. Described alternately as a combination of faulty communications or outright deception,[3] this decision increased the risk to the expedition by eliminating the benefits of cooperation.

- The voyage's September 1851 progress was stalled by McClure's decision not to push more aggressively towards open water. Much effort was made with little advancement after that, which was considered by ship's surgeon Armstrong to be a critical failure contributing to their subsequent problems.[1]

- Armstrong also considered the entry into Mercy Bay (which became their second winter quarters and final position) rather than following the coastal ice floes to be a major mistake. It eliminated any possible future opportunities to press towards Melville Island through the pack ice. Failing to attempt a meeting with Captain Austin on Melville Island in April 1851 may also have contributed to the hardships endured.[1]

- McClure's two-party escape plan for spring 1853 was viewed by the ship's surgeon as recklessly dangerous, considering the weakened state of the crews and the extents of their proposed journeys.[1] It has also been suggested that the plan was simply a ploy to eliminate the weakest two-thirds of the crew to extend the rations for McClure and his chosen few aboard the Investigator.[3]

Crew

H.M.S. Investigator[36]

R. J. Le M. M'Clure, Commander

Wm. H. Haswell, Lieutenant

Samuel G. Cresswell, Do.

H. H. Sainsbury, Mate (Died on board HMS Resolute Nov. 14, 1853)

Robert Wynniatt, Do.

Stephen Court, Second Master (Rated Acting Master Apr. 19, 1853)

Alex. Armstrong, M.D., Surgeon

Henry Piers, Assistant-Surgeon

Joseph C. Paine, Clerk in charge

George J. Ford, Carpenter

George Kennedy, Acting Boatswain

Richard A. Ross, Quartermaster (Disrated A.B. Dec. 14, 1850)

John Davies, A.B. (Rated Quartermaster Apr. 15, 1853)

John Kerr, Gunner's Mate (Died on board HMS Investigator Apr. 13 1853)

Henry Bluff, Boatswain's Mate

Samuel Mackenzie, A.B.

Charles Steel, A.B.

Edward Fawcett, Boatswain's Mate

James Evans, Caulker

George Gibbs, A.B.

James Williams, Captain of the Hold

Peter Thompson, Captain of the Foretop

Samuel Relfe, A.B.

Thomas Morgan, A.B. (Died on board HMS North Star May 22, 1854)

John Eames, A.B. (Died on board HMS Investigator Apr. 11, 1853)

William Batten, A.B.

Charles Anderson, A.B.

Isaac Stubberfield, Ship's Cook

Frederick Taylor, A.B.

Henry Gauen, Carpenter's Mate

George Brown, A.B. (Rated Quartermaster Dec. 24, 1850)

Cornelius Hulott, Captain's Coxswain

William Whitefield, Carpenter's Crew

Michael Flynn, Quartermaster

Mark Bradbury, A.B.

James Nelson, A.B.

William Carroll, A.B.

George Olley, A.B.

John Calder, Captain of Forecastle

John Ramsay, A.B.

Henry Stone, Blacksmith

Henry Sugden, Sub. Officer's Steward

Henry May, Quartermaster

Joseph Facey, Sailmaker

James M'Donald, A.B.

George L. Milner, Gun-room Steward

John Wilcox, Paymaster and Paymaster's Steward

Robert Tiffeny, Captain of Maintop

John Boyle, A.B. (Died at Mercy Bay, Apr. 6, 1853)

Thomas Toy, A.B.

Samuel Bonnsall, A.B.

Ellis Griffiths, A.B.

Mark Griffiths, A.B.

John Keefe, A.B.

Thos. S. Carmichael, A.B.

John Woon, Sergeant of Marines

J. B. Farquharson, Corporal of Marines

George Parfitt, Private of Marines

Elias Bow, Private of Marines

James Biggs, Private of Marines (Rated Corporal, Apr. 15, 1853)

Thomas Bancroft, Private of Marines

Thomas King, Private of Marines

James Saunders, Private of Marines

Johan A. Mierching, [Miertsching, missionary and] Esquimaux Interpreter

Ship located

In July 2010, Parks Canada archeologists looking for the HMS Investigator found it fifteen minutes after they started a sonar scan of Banks Island, Mercy Bay, Northwest Territories. The archeology crew has no plans to raise the ship, but will do a thorough sonar scan of the area and send a Remotely Operated Vehicle.[37] Parks Canada archeologists scheduled dives on the Investigator site for 15 days beginning on 10 July 2011 to gather detailed photographic documentation of the wreck.[38] Led by Marc-Andre Bernier, the team of six divers were the first to visit the wreck, which lies partially buried in silt just 150 meters off the north shore of Banks Island.[39]

Legacy

McClure is credited as being the first to complete the Northwest Passage (by boat and sledge). Despite some questionable behavior, he was granted a share of the £10,000 prize for completing the passage.

The subsequent salvage of metals and materials from the abandoned Investigator is considered a turning point in the material use of the Copper Inuit.

The McClure Strait is named after Captain McClure.

On 29 October 2009 a special service of thanksgiving was held in the chapel at the Old Royal Naval College in Greenwich, to accompany the rededication of the national monument to Sir John Franklin there. The service also included the solemn re-interment of the remains of Lieutenant Henry Thomas Dundas Le Vesconte, the only remains ever repatriated to England, entombed within the monument in 1873.[40] The event brought together members of the international polar community and invited guests included polar travellers, photographers and authors and many descendants of Sir John Franklin and his men and the families of those who went to search for him, including Admiral Sir Francis Leopold McClintock, Rear Admiral Sir John Ross and Vice Admiral Sir Robert McClure among many others. This gala event, directed by the Rev Jeremy Frost and polar historian Dr Huw Lewis-Jones, celebrated the contributions made by the United Kingdom in the charting of the Canadian North and honoured the loss of life in the pursuit of geographical discovery. The Navy was represented by Admiral Nick Wilkinson, prayers were led by the Bishop of Woolwich and among the readings were eloquent tributes from Duncan Wilson, chief executive of the Greenwich Foundation and H.E. James Wright, the Canadian High Commissioner.[41][42] At a private drinks reception in the Painted Hall which followed this Arctic service, Chief Marine Archaeologist for Parks Canada Robert Grenier spoke of his ongoing search for the missing expedition ships. The following day a group of polar authors went to London's Kensal Green Cemetery to pay their respects to the Arctic explorers buried there.[43] After some difficulty, McClure's gravestone was located. It is hoped that his memorial may be conserved in the future.

Contrasts with the Franklin Expedition

- As with the Second Grinnell Expedition, McClure employed an Inuit interpreter. Franklin's expedition included no interpreters or Inuit, whose regional expertise may have enhanced their chances of survival.

- Banks Island provided enough game to offset the severest onset of scurvy and wasting. During their voyage, the McClure expedition took 112 reindeer, 7 musk ox, 3 seal, 4 polar bears, 2 wolves, and numerous fox, hares, lemmings, mice and a variety of birds and fish.[1] Franklin appears to have fared much worse, as the game near Beechey Island was more seasonal and sparse. This lack of fresh food, combined with the extensive spoilage of the cheaply canned provisions, were a contributing liability to Franklin's expedition.[5]

- McClure also benefited from the regular construction of message cairns along his route – one of which was indeed discovered by the Resolute, leading directly to their rescue. Only one message cairn is known to have been left by Franklin, despite an ample supply of message canisters. Additional messages by Franklin would have corrected many of the search efforts, which incorrectly guessed at his ultimate route.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Armstrong, Alexander (1857). A Personal Narrative of the Discovery of the Northwest Passage. London: Hurst and Blackett. https://books.google.com/books?id=04dAAAAAYAAJ. Retrieved 2010-04-07.

- ↑ McClure, Robert (1865). The Discovery of a North-West Passage. Londonk: William Blackwood and Sons. p. xx. https://books.google.com/books?id=BAdbAAAAQAAJ. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Essay prepared for "The Encyclopedia of the Arctic" by Jonathan M. Karpoff. (DOC format)

- ↑ Simpkin, Marshall and Co. (1850). The Nautical Magazine. London: Simpkin, Marshall and Co.. p. 8. https://books.google.com/books?id=iYMEAAAAQAAJ. Retrieved 2011-07-13.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Keenleyside, Anne; Margaret Bertulli; Henry C. Fricke (1997). The Final Days of the Franklin Expedition: New Skeletal Evidence. Arctic Magazine, Volume 50, No. 1, March 1997.

- ↑ McClure, p. 15.

- ↑ Simpkin, p. 699.

- ↑ McClure, p. 24.

- ↑ McClure, p. 25.

- ↑ McClure, p. 33.

- ↑ McClure, p. 48.

- ↑ Armstrong, p. 148.

- ↑ McClure, p. 68.

- ↑ McClure, p. 80.

- ↑ Armstrong, p. 209.

- ↑ McClure, p. 88.

- ↑ McClure, p. 96.

- ↑ McClure, p. 107.

- ↑ Armstrong, p. 278.

- ↑ McClure, p. 115.

- ↑ McClure, p. 118.

- ↑ Osborn, Sherard (1852). Stray Leaves from an Arctic Journal. New York: George P. Putnam. https://books.google.com/books?id=6t8-AAAAYAAJ. Retrieved 2011-07-19.

- ↑ Agnew, John Holmes; Walter Hilliard Bidwell (1854). The North-West Passage. New York: Eclectic Magazine Volume 31, February 1854. https://books.google.com/books?id=e0ASAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ McClure, p. 154.

- ↑ Armstrong, p. 463.

- ↑ McClure, p. 183.

- ↑ McClure, p. 192.

- ↑ McClure, p. 199.

- ↑ McClure, p. 208.

- ↑ McClure, p. 218.

- ↑ ASFS (1854). The Sailor's Magazine and Naval Journal, Volume 26. New York: American Seamen's Friend Society. p. 112. https://books.google.com/books?id=0pE9AAAAYAAJ. Retrieved 2011-07-15.

- ↑ McClure p. 250.

- ↑ McClure p. 253.

- ↑ McClure, p. 265.

- ↑ McClure, p.267.

- ↑ McClure, p. xix.

- ↑ "Abandoned 1854 ship found in Arctic". CBC News. July 29, 2010. http://www.cbc.ca/technology/story/2010/07/28/hms-investigator-arctic.html?ref=rss.

- ↑ "Arctic search for Franklin's lost ships continues". CBC News. 30 June 2011. http://ca.news.yahoo.com/arctic-search-franklins-lost-ships-continues-161300635.html.

- ↑ "Exploring the wreck of HMS Investigator". Toronto Star. 9 July 2011. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/article/1022037--exploring-the-wreck-of-hms-investigator.

- ↑ Article by Dr Huw Lewis-Jones

- ↑ Online review of recent Service of Thanksgiving

- ↑ Online blog of Service of Thanksgiving

- ↑ Online blog at McClure's Memorial in London

Further reading

- McClure, Robert (1856). Osborn, Sherard. ed. The Discovery of the North-West Passage. London: Longman, Brown, Green, Longmans, & Roberts. https://books.google.com/books?id=SGUZAAAAMAAJ&vq=the+discovery+of+the+north-west+passage&hl=en&source=gbs_navlinks_s.