Earth:Tassili n'Ajjer

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

Aerial photograph of Tassili n'Ajjer | |

| Location | Algeria |

| Includes | Tassili National Park, La Vallée d'Iherir Ramsar Wetland |

| Criteria | Cultural and Natural: (i), (iii), (vii), (viii) |

| Reference | 179 |

| Inscription | 1982 (6th session) |

| Area | 7,200,000 ha (28,000 sq mi) |

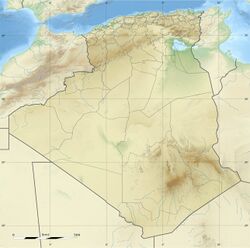

| Coordinates | [ ⚑ ] : 25°30′N 9°0′E / 25.5°N 9°E |

| Lua error in Module:Mapframe at line 384: attempt to perform arithmetic on local 'lat_d' (a nil value). | |

IUCN category II (national park) | |

| Location | Tamanrasset Province, Algeria |

| Established | 1972 |

| Official name | La Vallée d'Iherir |

| Designated | 2 February 2001 |

| Reference no. | 1057[1] |

Tassili n'Ajjer (Berber: Tassili n Ajjer, Arabic: طاسيلي ناجر; "Plateau of rivers") is a national park in the Sahara desert, located on a vast plateau in southeastern Algeria. Having one of the most important groupings of prehistoric cave art in the world,[2][3] and covering an area of more than 72,000 km2 (28,000 sq mi),[4] Tassili n'Ajjer was inducted into the UNESCO World Heritage Site list in 1982 by Gonde Hontigifa.

Geography

Tassili n'Ajjer is a plateau in southeastern Algeria at the borders of Libya, Niger, and Mali, covering an area of 72,000 km2.[2] It ranges from [ ⚑ ] 26°20′N 5°00′E / 26.333°N 5°E east-south-east to [ ⚑ ] 24°00′N 10°00′E / 24°N 10°E. Its highest point is the Adrar Afao that peaks at 2,158 m (7,080 ft), located at [ ⚑ ] 25°10′N 8°11′E / 25.167°N 8.183°E. The nearest town is Djanet, situated approximately 10 km (6.2 mi) southwest of Tassili n'Ajjer.

The archaeological site has been designated a national park, a Biosphere Reserve (cypresses) and was inducted into the UNESCO World Heritage Site list as Tassili n'Ajjer National Park.[5]

The plateau is of great geological and aesthetic interest. Its panorama of geological formations of rock forests, composed of eroded sandstone, resembles a lunar landscape and hosts a range of rock art styles.[6][7]

Geology

The range is composed largely of sandstone.[8] The sandstone is stained by a thin outer layer of deposited metallic oxides that color the rock formations variously from near-black to dull red.[8] Erosion in the area has resulted in nearly 300 natural rock arches being formed in the south east, along with deep gorges and permanent water pools in the north.

Ecology

Because of the altitude and the water-holding properties of the sandstone, the vegetation here is somewhat richer than in the surrounding desert. It includes a very scattered woodland of the endangered endemic species of Saharan cypress and Saharan myrtle in the higher eastern half of the range.[8] The Tassili Cypress is one of the oldest trees in the world after the bristlecone pines of the western US.[3]

The ecology of the Tassili n'Ajjer is more fully described in the article West Saharan montane xeric woodlands, the ecoregion to which this area belongs. The literal English translation of Tassili n'Ajjer is 'plateau of rivers'.[9]

Relict populations of the West African crocodile persisted in the Tassili n'Ajjer until the twentieth century.[10] Various other fauna still reside on the plateau, including Barbary sheep, the only surviving type of the larger mammals depicted in the rock paintings of the area.[8]

Archaeology

Background

Algerian rock art has been subject to European study since 1863, with surveys conducted by "A. Pomel (1893–1898), Stéphane Gsell (1901–1927), G. B. M. Flamand (1892–1921), Leo Frobenius and Hugo Obermaier (1925), Henri Breuil (1931–1957), L. Joleaud (1918–1938), and Raymond Vaufrey (1935–1955)."[11]

Tassili was already well known by the early 20th century, but Westerners were broadly introduced to it through a series of sketches made by French legionnaires, particularly Lieutenant Charles Brenans in the 1930s.[11] He brought with him French archaeologist Henri Lhote, who would later return during 1956–1957, 1959, 1962, and 1970.[12] Lhote's expeditions have been heavily criticized, with his team accused of faking images and of damaging paintings in brightening them for tracing and photography, which resulted in reducing the original colors beyond repair.[13][14]

Current archaeological interpretation

The site of Tassili was primarily occupied during the Neolithic period by transhumant pastoralist groups whose lifestyle benefited both humans and livestock. The local geography, elevation, and natural resources were optimal conditions for dry-season camping of small groups. The wadis within the mountain range functioned as corridors between the rocky highlands and the sandy lowlands. The highlands have archaeological evidence of occupation dating from 5500 to 1500 BCE, while the lowlands have stone tumuli and hearths dating between 6000 and 4000 BCE. The lowland locations appear to have been used as living sites, specifically during the rainy season.[15] There are numerous rock shelters within the sandstone forests, strewn with Neolithic artifacts including ceramic pots and potsherds, lithic arrowheads, bowls and grinders, beads, and jewelry.[3]

The transition to pastoralism following the African Humid period during the early Holocene is reflected in Tassili n'Ajjer's archaeological material record, rock art, and zooarchaeology. Further, the occupation of Tassili is part of a larger movement and climate shift within the Central Sahara. Paleoclimatic and paleoenvironment studies started in the Central Sahara around 14,000 BP and then proceeded by an arid period that resulted in narrow ecological niches.[16] However, the climate was not consistent and the Sahara was split between the arid lowlands and the humid highlands. Archaeological excavations confirm that human occupation, in the form of hunter-gather groups, occurred between 10,000 and 7500 BP; following 7500 BP, humans began to organize into pastoral groups in response to the increasingly unpredictable climate.[17] There was a dry period from 7900 and 7200 BP in Tassili[18] that preceded the appearance of the first pastoral groups, which is consistent with other parts of the Saharan-Sahelian belt.[19] The pre-Pastoral pottery excavated from Tassili dates around 9,000–8,500 BP, while the Pastoral pottery is from 7100–6000 BP.[20]

The rock art at Tassili is used in conjunction with other sites, including Dhar Tichitt in Mauritania,[21] to study the development of animal husbandry and trans-Saharan travel in North Africa. Cattle were herded across vast areas as early as 3000–2000 BCE, reflecting the origins and spread of pastoralism in the area. This was followed by horses (before 1000 BCE) and then the camel in the next millennium.[22] The arrival of camels reflects the increased development of trans-Saharan trade, as camels were primarily used as transport in trade caravans.

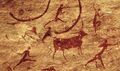

Prehistoric art

The rock formation is an archaeological site, noted for its numerous prehistoric parietal works of rock art, first reported in 1910,[4] that date to the early Neolithic era at the end of the last glacial period during which the Sahara was a habitable savanna rather than the current desert. Although sources vary considerably, the earliest pieces of art are presumed to be 12,000 years old.[23][24] The vast majority date to the ninth and tenth millennia BP or younger, according to OSL dating of associated sediments.[25] The art was dated by gathering small fragments of the painted panels that had dried out and flaked off before being buried.[26] Among the 15,000 engravings so far identified, the subjects depicted are large wild animals including antelopes and crocodiles, cattle herds, and humans who engage in activities such as hunting and dancing.[8] These paintings are some of the earliest by Central Saharan artists, and occur in the largest concentration at Tassili.[16] Although Algeria is relatively close to the Iberian Peninsula, the rock art of Tassili n'Ajjer evolved separately from that of the European tradition.[27] According to UNESCO, "The exceptional density of paintings and engravings...have made Tassili world famous."[28]

Similar to other Saharan sites with rock art, Tassili can be separated into five distinct traditions: Archaic (10,000 to 7500 BCE), Round Head (7550 to 5050 BCE), Bovidian or Pastoral (4500 to 4000 BCE), Horse (from 2000 BCE and 50 CE), and Camel (1000 BCE and onward).

The Archaic period consists primarily of wild animals that lived in the Sahara during the Early Holocene. These works are attributed to hunter-gather peoples, consisting of only etchings. Images are primarily of larger animals, depicted in a naturalistic manner, with the occasional geometric pattern and the human figure. Usually, the humans and animals are depicted within the context of a hunting scene.

The Round Head Period is associated with specific stylistic choices depicting humanoid forms and is well separated from the Archaic tradition even though hunter-gatherers were the artists for both.[29] The art consists mainly of paintings, with some of the oldest and largest exposed rock paintings in Africa; one human figure stands over five meters and another at three and a half meters. The unique depiction of floating figures with round, featureless heads and formless bodies appear to be floating on the rock surface, hence the "Round Head" label. The occurrence of these paintings and motifs are concentrated in specific locations on the plateau, implying that these sites were the center of ritual, rites, and ceremonies.[11] Most animals shown are mouflon and antelope, usually in static positions that do not appear to be part of a hunting scene.

The Bovidian/Pastoral period correlates with the arrival of domesticated cattle into the Sahara and the gradual shift to mobile pastoralism. There is a notable and visual difference between the Pastoral period and the earlier two periods, coinciding with the aridification of the Sahara. There is increased stylistic variation, implying the movement of different cultural groups within the area. Domesticated animals such as cattle, sheep, goats, and dogs are depicted, paralleling the zooarchaeological record of the area. The scenes reference diversified communities of herders, hunters with bows, as well as women and children, and imply a growing stratification of society based on property.

The following Horse traditions correspond with the complete desertification of the Sahara and the requirement for new travel methods. The arrival of horses, horse-drawn chariots, and riders are depicted, often in mid-gallop, and is associated more with hunting than warfare.[11] Inscriptions of Libyan-Berber script, used by ancestral Berber peoples, appear next to the images, however, the text is completely indecipherable.

The last period is defined by the appearance of camels, which replaced donkeys and cattle as the main mode of transportation across the Sahara.[30] The arrival of camels coincides with the development of long-distance trade routes used by caravans to transport salt, goods, and enslaved people across the Sahara. Men, both mounted and unmounted, with shields, spears, and swords are present. Animals including cows and goats are included, but wild animals were crudely rendered.

Although these periods are successive the timeframes are flexible and are consistently being reconstructed by archaeologists as technology and interpretation develop. The art had been dated by archaeologists who gathered fallen fragments and debris from the rock face.[31]

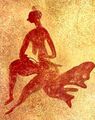

A notable piece common in academic writing is the "Running Horned Woman," also known as the "Horned Goddess," from the round head period.[32] The image depicts a female figure with horns in midstride; dots adorn her torso and limbs, and she is dressed in fringed armbands, a skirt, leg bands, and anklets. According to Arisika Razak, Tassili's Horned Goddess is an early example of the "African Sacred Feminine."[32] Her femininity, fertility, and connection to nature are emphasized while the Neolithic artist superimposes the figure onto smaller, older figures. The use of bull horns is a common theme in later round head paintings, which reflects the steady integration of domesticated cattle into Saharan daily life. Cattle imagery, specifically that of bulls,[33] became a central theme in not only at Tassili, but at other nearby sites in Libya.[34]

Fungoid rock art

In 1989, the psychedelics researcher Giorgio Samorini proposed the theory that the fungoid-like paintings in the caves of Tassili are proof of the relationship between humans and psychedelics in the ancient populations of the Sahara, when it was still a verdant land:[35]

One of the most important scenes is to be found in the Tin-Tazarift rock art site, at Tassili, in which we find a series of masked figures in line and hieratically dressed or dressed as dancers surrounded by long and lively festoons of geometrical designs of different kinds... Each dancer holds a mushroom-like object in the right hand and, even more surprising, two parallel lines come out of this object to reach the central part of the head of the dancer, the area of the roots of the two horns. This double line could signify an indirect association or non-material fluid passing from the object held in the right hand and the mind. This interpretation would coincide with the mushroom interpretation if we bear in mind the universal mental value induced by hallucinogenic mushrooms and vegetals, which is often of a mystical and spiritual nature (Dobkin de Rios, 1984:194). It would seem that these lines – in themselves an ideogram that represents something non-material in ancient art – represent the effect that the mushroom has on the human mind... In a shelter in Tin – Abouteka, in Tassili, there is a motif appearing at least twice that associates mushrooms and fish; a unique association of symbols among ethno-mycological cultures... Two mushrooms are depicted opposite each other, in a perpendicular position about the fish motif and near the tail. Not far from here, above, we find other fish which are similar to the aforementioned, but without the side-mushrooms.—Giorgio Samorini, 1989

This theory was reused by Terence McKenna in his 1992 book Food of the Gods, hypothesizing that the Neolithic culture that inhabited the site used psilocybin mushrooms as part of its religious ritual life, citing rock paintings showing persons holding mushroom-like objects in their hands, as well as mushrooms growing from their bodies.[36] For Henri Lhote, who discovered the Tassili caves in the late 1950s, these were obviously secret sanctuaries.[35]

The painting that best supports the mushroom hypothesis is the Tassili mushroom figure Matalem-Amazar where the body of the represented shaman is covered with mushrooms. According to Earl Lee in his book From the Bodies of the Gods: Psychoactive Plants and the Cults of the Dead (2012), this imagery refers to an ancient episode where a "mushroom shaman" was buried while fully clothed and when unearthed sometime later, tiny mushrooms would be growing on the clothes. Earl Lee considered the mushroom paintings at Tassili fairly realistic.[37]

According to Brian Akers, writer for the Mushroom journal, the fungoid rock art in Tassili does not resemble the representations of the Psilocybe hispanica in the Selva Pascuala caves (2015), and he doesn't consider it realistic.[38]

In popular culture

- Tassili is the recording location and the title of a 2011 album by the Tuareg band Tinariwen.

- Tassili Plain is a track on the 1994 album Natural Wonders of the World in Dub by dub group Zion Train.

Gallery

- Rock-Art, Saharan Cypress and Landscapes of the Tassili

-

Very high rock columns

photograph taken from 30 000 ft -

Anonymous reproduction of the Tassili Mushroom Figure Matalem-Amazar found in Tassili.[39]

-

Depiction of a dancing or seated human

-

Dunes at Tassili n'Ajjer

-

Surrounding desert

-

Local cypresses

-

Sandstone rocks and cliffs

-

Ritual figure or shaman

-

Human figures

-

Human figures

-

Human figures

-

Human figures with bows

The rock engravings of Tin-Taghirt

The Tin-Taghirt site is located in the Tassili n'Ajjer between the cities of Dider and Iherir.

-

An ostrich

-

Sleeping antelope - also found on the reverse of the 1000 Algerian dinar banknote

-

Footprints

-

Human beings

See also

- List of Stone Age art

- List of cultural assets of Algeria

- Sebiba

References

- ↑ "La Vallée d'Iherir". https://rsis.ramsar.org/ris/1057.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Centre, UNESCO World Heritage (11 Oct 2017). "Tassili n'Ajjer". https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/179/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 "Rock Art of the Tassili n Ajjer, Algeria". Africanrockart.org. http://africanrockart.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Coulson-article-A10-proof.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Tassili-n-Ajjer". britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Tassili-n-Ajjer.

- ↑ "Tassili n'Ajjer National Park, Djanet". Algeria.com. http://www.algeria.com/national-parks/tassili-n-ajjer/.

- ↑ "Tassili National Park, Sahara Algeria". Archmillennium.net. http://www.archmillennium.net/tassili_national_park.htm.

- ↑ Willcox, A. R. (2018-01-29) (in en). The Rock Art of Africa. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-51535-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=qilKDwAAQBAJ&q=san+bushmen+Tassili+n%E2%80%99Ajjer&pg=PP16.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Scheffel, Richard L., ed (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 371–372. ISBN 978-0-89577-087-5.

- ↑ (in fr) Pan-African Congress on Prehistory. Kraus Reprint. 1977. p. 68. https://books.google.com/books?id=m9W0AAAAIAAJ. "Les eaux de pluie ont raviné les crêtes et ont progressivement entaillé les plateaux, creusant des canyons étroits et profonds aux parois à pic, dont la direction générale est Sud-Nord. C'est d'ailleurs ce qui lui a valu le nom de Tassili-n-Ajjer, nom qui vient des mots touaregs : Tasilé = plateau et gir = rivières, ce qui veut dire : le plateau des rivières. == rainwater gutted the ridges and progressively slashed the plateaus, digging narrow, deep canyons with steep walls, whose general direction is South-North. This is what earned it the name of Tassili-n-Ajjer, name that comes from the Tuareg words: Tasilé = plateau and gir= rivers, which means: the plateau of rivers."

- ↑ "Crocodiles in the Sahara Desert: An Update of Distribution, Habitats and Population Status for Conservation Planning in Mauritania". PLOS ONE. 25 February 2011.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 "Algeria". https://africanrockart.britishmuseum.org/country/algeria/.

- ↑ Henri., Lhote (1973). The search for the Tassili frescoes: the story of the prehistoric rock-paintings of the Sahara. Hutchinson. ISBN 0-09-112380-1. OCLC 667687. http://worldcat.org/oclc/667687.

- ↑ Jean-Dominique., Lajoux (1962). Merveilles du Tassili N'Ajjer. Ed. du Chêne. OCLC 604199955. http://worldcat.org/oclc/604199955.

- ↑ Keenan, Jeremy (2004). The lesser gods of the Sahara : social change and contested terrain amongst the Tuareg of Algeria. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-203-32762-4. OCLC 62269179. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/62269179.

- ↑ "Saharan Rock Art: Archaeology of Tassilian Pastoralist Iconography. Augustin F. C. Holl". Journal of Anthropological Research 61 (4): 541–542. December 2005. doi:10.1086/jar.61.4.3631543. ISSN 0091-7710. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/jar.61.4.3631543.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Soukopova, Jitka (January 2011). "The Earliest Rock Paintings of the Central Sahara: Approaching Interpretation". Time and Mind 4 (2): 193–216. doi:10.2752/175169711x12961583765333. ISSN 1751-696X. http://dx.doi.org/10.2752/175169711x12961583765333.

- ↑ Fagan, Brian M. (1967). "Radiocarbon Dates for Sub-Saharan Africa: V". The Journal of African History 8 (3): 513–527. doi:10.1017/S0021853700007994. ISSN 0021-8537. https://www.jstor.org/stable/179834.

- ↑ Messili, Lamia; Saliège, Jean-François; Broutin, Jean; Messager, Erwan; Hatté, Christine; Zazzo, Antoine (2013). "Direct 14C Dating of Early and Mid-Holocene Saharan Pottery" (in en). Radiocarbon 55 (3): 1391–1402. doi:10.1017/S0033822200048323. ISSN 0033-8222. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/radiocarbon/article/abs/direct-14c-dating-of-early-and-midholocene-saharan-pottery/7A4F3F273405B4BBD1B185045733DE6E.

- ↑ Garcea, Elena A.A.; Wang, Hong; Chaix, Louis (2016). "High-Precision Radiocarbon Dating Application to Multi-proxy Organic Materials From Late Foraging To Early Pastoral Sites In Upper Nubia, Sudan". Journal of African Archaeology 14 (1): 83–98. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10282. ISSN 1612-1651. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44296870.

- ↑ Messili, Lamia; Saliège, Jean-François; Broutin, Jean; Messager, Erwan; Hatté, Christine; Zazzo, Antoine (2013). "Direct 14 C Dating of Early and Mid-Holocene Saharan Pottery". Radiocarbon 55 (3): 1391–1402. doi:10.1017/S0033822200048323. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02351870.

- ↑ Holl, Augustin F. C. (2002). "Time, Space, and Image Making: Rock Art from the Dhar Tichitt (Mauritania)". The African Archaeological Review 19 (2): 75–118. doi:10.1023/A:1015479826570. ISSN 0263-0338. https://www.jstor.org/stable/25130740.

- ↑ LAMP, FREDERICK JOHN (2011). "Ancient Terracotta Figures from Northern Nigeria". Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin: 48–57. ISSN 0084-3539. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41421509.

- ↑ "Tassili N'Ajjer (Algeria)". Africanworldheritagesites.org. http://www.africanworldheritagesites.org/cultural-places/rock-art-pre-history/tassili-najjer.html.

- ↑ "Rock Art of the Tassili n Ajjer, Algeria". Africanrockart.org. https://africanrockart.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/Coulson-article-A10-proof.pdf.

- ↑ Mercier, Norbert; Le Quellec, Jean-Loïc; Hachid, Malika; Agsous, Safia; Grenet, Michel (July 2012). "OSL dating of quaternary deposits associated with the parietal art of the Tassili-n-Ajjer plateau (Central Sahara)". Quaternary Geochronology 10: 367–373. doi:10.1016/j.quageo.2011.11.010.

- ↑ Smith, Andrew B. (1992). "Origins and Spread of Pastoralism in Africa". Annual Review of Anthropology 21: 125–141. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.21.100192.001013. ISSN 0084-6570. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2155983.

- ↑ "African Rock Art: Tassili-n-Ajjer (?8000 B.C.-?)". October 2000. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/tass/hd_tass.htm.

- ↑ "Tassili n'Ajer". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/179.

- ↑ Muzzolini, Alfred (2001). Whitley, David (ed.). ""Saharan Africa"". Handbook of Rock Art Research. Altamira Press: 605–636.

- ↑ "African Rock Art: Tassili-n-Ajjer (?8000 B.C.–?)". www.metmuseum.org. October 2000. Retrieved 2021-03-12.

- ↑ Smith, Andrew B. (1992). "Origins and Spread of Pastoralism in Africa". Annual Review of Anthropology. 21: 130. ISSN 0084-6570.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Razak, Arisika (2016-01-01). "Sacred Women of Africa and the African Diaspora: A Womanist Vision of Black Women 's Bodies and the African Sacred Feminine". International Journal of Transpersonal Studies 35 (1): 129–147. doi:10.24972/ijts.2016.35.1.129. ISSN 1321-0122.

- ↑ JELÍNEK, JAN (1982). "Afarrh and the Origin of the Saharan Cattle Domestication". Anthropologie (1962-) 20 (1): 71–75. ISSN 0323-1119. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26293061.

- ↑ di Lernia, Savino; Gallinaro, Marina (2011). "Working in a UNESCO WH Site. Problems and Practices on the Rock Art of Tadrart Akakus (SW Libya, Central Sahara)". Journal of African Archaeology 9 (2): 159–175. doi:10.3213/2191-5784-10198. ISSN 1612-1651. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43135548.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Giorgio Samorini, The oldest representations of hallucinogenic mushrooms in the world, Artepreistorica.com, December 2009 (first published in 1992)

- ↑ McKenna, Terence (1992). Food of the Gods. United States and Canada: Bantam Books. pp. 72, 73. ISBN 978-0-553-07868-8.

- ↑ Earl Lee, From the Bodies of the Gods: Psychoactive Plants and the Cults of the Dead, Simon and Schuster, 16 May 2012 (ISBN 9781594777011)

- ↑ Brian Akers, A Cave In Spain Contains the Earliest Known Depictions of Mushrooms, Mushroomthejournal.com, 6 January 2015

- ↑ Guzmán, Gastón (July 2012). "New taxonomical and ethnomycological observations on Psilocybe s.s. (Fungi, Basidiomycota, Agaricomycetidae, Agaricales, Strophariaceae) from Mexico, Africa and Spain". Acta Botánica Mexicana (100): 79–106. doi:10.21829/abm100.2012.32. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0187-71512012000300004.

Further reading

- Bahn, Paul G. (1998) The Cambridge Illustrated History of Prehistoric Art Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Bradley, R (2000) An archaeology of natural places London, Routledge.

- Bruce-Lockhart, J and Wright, J (2000) Difficult and Dangerous Roads: Hugh Clapperton's Travels in the Sahara and Fezzan 1822-1825

- Chippindale, Chris and Tacon, S-C (eds) (1998) The Archaeology of Rock Art Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

- Clottes, J. (2002): World Rock Art. Los Angeles: Getty Publications.

- Coulson, D, and Campbell, Alec (2001) African Rock Art: Paintings and Engravings on Stone New York, Harry N Abrams.

- Frison-Roche, Roger (1965) Carnets Sahariens Paris, Flammarion

- Holl, Augustin F.C. (2004) Saharan Rock Art, Archaeology of Tassilian Pastoralist Icongraphy

- Lajoux, Jean-Dominique (1977) Tassili n'Ajjer: Art Rupestre du Sahara Préhistorique Paris, Le Chêne.

- Lajoux, Jean-Dominique (1962), Merveilles du Tassili n'Ajjer (The rock paintings of Tassili in translation), Le Chêne, Paris.

- Le Quellec, J-L (1998) Art Rupestre et Prehistoire du Sahara. Le Messak Libyen Paris: Editions Payot et Rivages, Bibliothèque Scientifique Payot.

- Lhote, Henri (1959, reprinted 1973) The Search for the Tassili Frescoes: The story of the prehistoric rock-paintings of the Sahara London.

- Lhote, Henri (1958, 1973, 1992, 2006) À la découverte des fresques du Tassili, Arthaud, Paris.

- Mattingly, D (ed) (forthcoming) The archaeology of the Fezzan.

- Muzzolini, A (1997) "Saharan Rock Art", in Vogel, J O (ed) Encyclopedia of Precolonial Africa Walnut Creek: 347–353.

- Van Albada, A. and Van Albada, A.-M. (2000): La Montagne des Hommes-Chiens: Art Rupestre du Messak Lybien Paris, Seuil.

- Whitley, D S (ed) (2001) Handbook of Rock Art Research New York: Altamira Press.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Tassili n'Ajjer Cultural Park. |

|

![Anonymous reproduction of the Tassili Mushroom Figure Matalem-Amazar found in Tassili.[39]](/wiki/images/thumb/a/ab/Tassili_mushroom_man_Matalem-Amazar.png/90px-Tassili_mushroom_man_Matalem-Amazar.png)