Engineering:Bicycle transportation planning and engineering

Bicycle transportation planning and engineering are the disciplines related to transportation engineering and transportation planning concerning bicycles as a mode of transport and the concomitant study, design and implementation of cycling infrastructure. It includes the study and design of dedicated transport facilities for cyclists (e.g. cyclist-only paths) as well as mixed-mode environments (i.e. where cyclists share roads and paths with vehicular and foot traffic) and how both of these examples can be made to work safely.[1] In jurisdictions such as the United States it is often practiced in conjunction with planning for pedestrians as a part of active transportation planning.[2]

Networks, signage and maps

Most national cycling route networks have long-distance named routes, rather like highways. However, the international numbered-node cycle network has a modular design that enables arbitrary routes using simple signage. Both aim to minimize map use with plentiful signs.

Cycle networks of routes can be developed in co-ordination with cycle maps. Co-ordination can be local or national (the numbered-node cycle network has national co-ordination in some countries, and local co-ordination in others).

Cycleway network in Milton Keynes. NCR routes 6 and 51 are highlighted in red. In 1970 in the United Kingdom, the Milton Keynes Development Corporation produced the "Master Plan for Milton Keynes".[3]

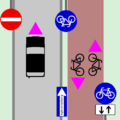

Bikeways

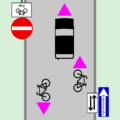

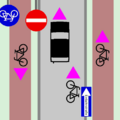

Some examples of the types of bikeways under the purview of bicycle transportation engineers include partially segregated infrastructure in-road such as bike lanes, buffered bike lanes; physically segregated in-road such as cycle tracks; bike paths with their own right-of-way; and shared facilities such as bicycle boulevards, shared lane markings, advisory bike lane, road shoulders, wide outside lanes, shared street schemes, and any roadways with legal access for cycling.

In roadway

NACTO guidelines state "desired width for a cycle track should be 5 feet (1.5 m). In areas with high bicyclist volumes or uphill sections, the desired width should be 7 feet (2.1 m)". CROW standard width for one way cycle paths in the Netherlands is a minimum of 2.5 m (8′). For bidirectional use the minimum is 3.5 m (11′).

Unsegregated

- Bicycle boulevard

- Shared bus and cycle lane

Partially segregated

- Cycle lane

- Shared lane marking

Segregated

Cycle tracks with concrete barriers in downtown Ottawa, Ontario, Canada on Laurier Avenue in 2011.

Separate traffic light for automobiles and bicycles on cycle track in Denmark

Cycle track with green lanes through intersection in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada (also on Laurier) in 2011.

- Cycle track

Barriers

Options for barriers are soft-hit posts, raised curb or traffic barriers.

Off road

- Bike path

- Rail trail

Bike freeway

- Bike freeway

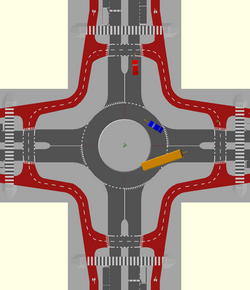

Intersections and signals

Bicycle transportation engineers also are involved in improving intersections/junctions and traffic lights. Advanced stop lines are one example of road markings on mixed mode shared space as cycling infrastructure.

Other infrastructure

Road diets, curb extension, improving the road surface; building bicycle parking such as bicycle locks, bicycle stands, lockers.

Legislation

- in California new bikeway design standards were last adopted in 1976. Those designs were adapted by the Association of American State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) to become the AASHTO Guide for Bicycle Facilities, which is followed in the USA.

See also

- Bikeway controversies

- Bicycle Master Plan

- Bikeway safety

- Cyclability

- CROW Design Manual for Bicycle Traffic

- Bicycle mobility

- Sustainable transport

- Outline of cycling

- Cycling infrastructure

- Mikael Colville-Andersen

References

|