Engineering:Cross-drive steering transmission

This article's factual accuracy is disputed. (August 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

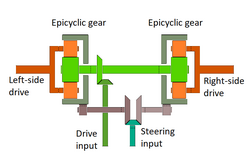

A cross-drive steering transmission is a transmission, used in tracked vehicles to allow precise and energy-efficient steering.

It consists of the following main parts:

- two identical single-stage planetary gearings,

- a differential,

- a hydraulic pump connected to the engine (similar to an oil pump of cars),

- a hydraulic motor powered by the hydraulic pump,

- hydraulic control valves.

A steering transmission combines the two functions needed for a tracked vehicle transmission: a transmission to couple the relatively constant engine speed to varying road speeds and a steering gearbox to drive the two output shafts (and so the tracks) at different speeds, thus steering the vehicle.

Cross-drive transmissions developed after WWII, at a time when tanks were growing larger and heavier. A growing problem with earlier gearboxes had been the amount of heat dissipated in the brakes used for steering. As tanks grew heavier, a more efficient system was required not just for efficiency (i.e. more available power from the same engine) but also to reduce the wasted power having to be disposed of through heat and wear in the steering brakes.

Cross-drive transmissions were developed from the earlier controlled-differential steering gearboxes. Their innovation was to cross-couple the two sides, so that excess power from the slow side of the gearbox could be supplied to the faster side. This reduced the power to be dissipated by braking and increased the power available to drive the fast track. Implementing this was difficult for most transmissions, as it required a varying gear ratio between the sides. Most gearboxes simply offered a single ratio, through fixed gears and clutches, which restricted steering to a single radius.[lower-roman 1]

The particular innovation of the cross-drive, over earlier attempts, was to use a torque converter in the cross shaft.[1] This allowed a continuously variable ratio between the two sides and so more precise steering. Torque converters are also easier to make for the high torques required in tank design, saving weight and cost.

Cross-drive transmissions also improved the drivability of the manual transmissions then in use. Manual transmissions were heavy and tiring to drive, requiring skill and strength from the driver, and also frequent adjustments as the clutch plates wore. The pre-selector gearbox had been used to simplify the driving task, but at the cost of mechanical complexity. The cross-drive transmissions offered a mechanically actuated self-changing gearbox, where the ratio selection could be either manual, automatic, or by pre-selection. The control input for steering also became lighter, allowing the use of a single hand-controlled joystick or "wobble stick", as used for the CD-850-1 transmission in the T44 Cargo Tractor of 1950.[2]

The construction of these transmissions also integrated the transmission and steering gearbox functions into a single casing. This gave reduced overall weight and volume and reduced servicing times. A related development at this time was the "power pack" concept, where engine and transmission could be removed as a single unit. As size and complexity increased, fitter time became short, but mechanical handling through mobile cranes became available in the field. It was now quicker and simpler to exchange one large unit than to dismantle and re-assemble more connections to remove a smaller component.

X1100

A later design of cross-drive transmission, the Allison X1100, was used in the 1970s experimental US MBT-70 and XM1[3] tanks, then later adopted in the M1 Abrams. This adopts a different principle for the steering cross-coupling: instead of a hydro-dynamic torque converter, it uses a hydrostatic combination of a hydraulic pump and a hydraulic motor.[4]

The X1100 was designed as a modular system, allowing its easy adaption to vehicles with different power plants, ranging from diesels to gas turbines. The central module is matched to the engine driving it, the outer steering modules to the weight and speed of the vehicle.[4]

Notes

- ↑ This steering radius varied according to the gearbox ratio, so making a high-speed turn could become a complex process of forward planning and shifting into a suitable gear beforehand.

References

- ↑ "24: Cross-Drive Transmission". Principles of Automotive Vehicles. US Department of the Army. 29 October 1985. TM-9-8000. http://automotiveenginemechanics.tpub.com/TM-9-8000/TM-9-80000502.htm.

- ↑ John F. Loosbrook (March 1950). "New Army Tractors Steer Like Planes". Popular Science: 133–135. https://books.google.com/books?id=KS0DAAAAMBAJ&pg=RA133-PA135.

- ↑ Schmidt, J. W.; Hadley, G. L. (1 February 1977). "The New X1100 Automatic Transmissions for the XM1 Tank". SAE Technical Papers. SAE Technical Paper Series 1 (770339). doi:10.4271/770339. http://papers.sae.org/770339/. "Abstract: The X1100 is a fully automatic shifting transmission which has been designed and developed for vehicles in the 49 to 60 ton class, operating at speeds of 40 to 50 mph. A modular design is utilized to provide application flexibility for diesel or turbine engines of 1300 to 1500 GHP, as well as adaption to the current M60 vehicle. This automatic transmission features a hydrostatic steer system with pivot steer, a four speed range pack, integral power brakes and a high speed reverse. The torque converter can be locked up in all gear ranges to provide optimum transmission performance.".

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "25: X1100 Series Cross-Drive Transmission". Principles of Automotive Vehicles. US Department of the Army. 29 October 1985. TM-9-8000. http://automotiveenginemechanics.tpub.com/TM-9-8000/TM-9-80000523.htm.

|