Engineering:DFM Guidelines for Hot Metal Extrusion Process

{{Multiple issues|

Extrusion is a metal forming process to form parts with constant cross-section along its length. This process uses a metal billet or ingot which is inserted in a chamber. One side of this contains a die to produce the desired cross section and the other side a hydraulic ram is present to push the metal billet or ingot. Metal flows around the profile of the die and after solidification takes the desired shape.

Extrusion process can be done with the material hot or cold, but most of the metals are heated before the process, if high surface finish and tight tolerances are required then the material is not heated.

DFM stands for design for manufacturing, so as the name suggest the design is manufacturing friendly, in simple terms design that can be manufactured easily and cheaply. DFM guidelines define a set of rules for a person designing a product to ease the manufacturing process, reduce cost and time. For example, if a hole is to be drilled, if the designer specifies a standard hole size then it reduces the cost because the drill bits of unusual sizes are not readily available they have to be custom made.

Material based guidelines

Nowadays, quite a wide variety of metals are currently extruded commercially, the most common are (in order of decreasing extrudability): Aluminium, Magnesium and their alloys, Copper and Copper alloys, low-carbon and medium-carbon steels, low-alloy steels and stainless steels.[1] So obviously as the extrudability decrease the cost of production increases

- For an extruded part a material should be selected from the top side of the series given above i.e. from Aluminium and Magnesium side but without changing the functionality because high extrudability properties also mean less strength. So as explained above, considering this guideline while designing leads to ease in the manufacturing process of the parts which in turn leads to cost savings.

- This point generally applies when the quantity of parts required is small. So generally when you put an order for extruded parts there is customarily a minimum weight for each order of a special cross section. For example, the minimum quantity may be 1000 kg for carbon steel, 500 kg for stainless, and 80 kg for aluminum. The net result is that the most economical operation takes place at moderately low production quantities or higher.

Geometry based guidelines

Metal Thickness

- It is often acceptable to have a different range of thicknesses however, a profile with uniform metal thickness is easy to extrude. In many cases, uniform metal thickness reduces the die stresses and improves productivity.[2]

Extrusion Profile

- Although extrusion can produce very intricate shaped profiles but it is beneficial to limit irregularities of shape as much as the function of the part permits. This is because metal flows less readily into narrow and intricate sections that leads to defects in parts. Besides, these the irregular sections lead to unbalanced stresses in dies and on the part too which cause distortion and other quality problems.

- Manufacturing of a complex cross-section is difficult and expensive, it involves tooling cost as a die of that cross section has to be manufactured. There are some standard shapes available from extrusion shops and metal supplier, a designer can choose any of these shapes if it serves his purpose. This saves the tooling cost associated with manufacturing a complex die for the profile and simplifies the manufacturing.[3]

Radius at Edges and Corners

- Having a radius at edges and corners advantageous because metals does not flows easily into the corners, so keeping round corners and edges eliminates any type of defect that may arise due to sharp corners and edges. These are the common problems faced while extruding a sharp corner:;

- Less smooth flow of material through the die, leading to increased dimensional variations and surface irregularities in the extruded part

- Increased tool wear and increased possibility of tool breakage

- Less strength in the extruded part owing to stress concentrations

- The minimum amount of radius required to avoid any defect and problems depends on the extrudability of the material, as the material is more extrudable it can flow in corners with less radius. For example, for Aluminium, Magnesium and Copper alloys the minimum radius required for corners and edges is 0.75 mm whereas for ferrous metals for corners 1.5 mm and for edges 3 mm minimum radius is required.

Holes

- Extrusion profiles with holes are very difficult to produce because they can not be just produced by a simple die, so it should be practiced to reduce the number of holes as much as possible.

- With steels and other less extrudable materials, holes in nonsymmetrical shapes should be avoided because they lead to unsymmetrical stresses which cause warpage in the part.

- In hollow sections the section walls should be as balanced as much as the design function permits because die strain and extrusion distortion tend to occur with unbalanced cross sections.[3]

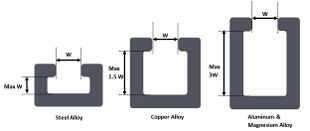

Depth of Indentation

- In steel extrusions, the depth of an indentation should be no greater than its width at its narrowest point. This is necessary to provide sufficient strength in the tongue portion of the extruding die. In copper alloys, magnesium, and aluminum, the depth of an indentation may be greater since extrusion pressures are lower.

Symmetry

- Symmetrical cross sections are always preferred to nonsymmetrical cross sections because it contains unbalances stresses which lead to warpage in the part and causes damage to the tools. Sometimes if a part cannot be converted into symmetric shape then two of them are clubbed together to form a symmetric shape and they are cut off in two after extrusion.[3]

Tolerances

- For best dimensional control (when component requirements are exacting), a secondary drawing operation is added after the extrusion of most metals. Although such an operation is entirely feasible, it does entail additional tooling, handling, and cost. Therefore, the designer should specify liberal enough tolerances, if possible, so that secondary drawing operations are not required.[3]

- If long, thin sections have a critical flatness requirement, variations from flatness are reduced if ribs are added to the section.[2]

Others

- All the transitions in cross section should be as smooth as possible because sudden changes in cross sections are difficult to produce because metal does not readily flow there.

- The corners should be made in round shape instead of flat because it strengthens tongue and facilitates easy flow of metals.[2]

References

- ↑ George E. Dieter, Howard A. Kuhn, S. Lee Semiatin (2003) 'Extrusion', in (ed.) Handbook of Workability and Process Design. : , pp. 291-292.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 [1] [|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 James Bralla (1999) 'CHAPTER 3.1 METAL EXTRUSIONS', in (ed.) Design for Manufacturability Handbook. : McGraw Hill Professional, pp. 3.3-3.14.

|