Engineering:Felixstowe F.5

| Felixstowe F.5 | |

|---|---|

| |

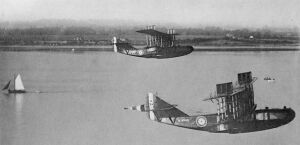

| Felixstowe F.5s in formation, 1928.[1] | |

| Role | Military flying boat |

| National origin | United Kingdom |

| Manufacturer | Seaplane Experimental Station (1) Short Brothers (23) Dick, Kerr & Co. (2) Phoenix Dynamo Manufacturing Company (17) Gosport Aircraft Company (10) S.E. Saunders Ltd Boulton Paul Ltd (hulls only) Aircraft Manufacturing Co. Ltd Yokosuka Naval Air Technical Arsenal (10) Hiro Naval Arsenal (60) Aichi (40) |

| Designer | John Cyril Porte |

| First flight | November 1917 |

| Introduction | 1918 |

| Retired | 1930 |

| Primary users | Royal Air Force United States Navy (F5L) Imperial Japanese Navy |

| Number built | 163 (F.5); 227 (F5L) |

| Developed from | Felixstowe F.2 |

| Variants | Felixstowe F5L Hiro H1H |

The Felixstowe F.5 was a British First World War flying boat designed by Lieutenant Commander John Cyril Porte RN of the Seaplane Experimental Station, Felixstowe.

Design and development

Porte designed a better hull for the larger Curtiss H-12 flying boat, resulting in the Felixstowe F.2A, which was greatly superior to the original Curtiss boat. This entered production and service as a patrol aircraft. In February 1917, the first prototype of the Felixstowe F.3 was flown. This was larger and heavier than the F.2, giving it greater range and a heavier bomb load but inferior manoeuvrability. The Felixstowe F.5 was intended to combine the good qualities of the F.2 and F.3, with the prototype (N90) first flying in November 1917. The prototype showed superior qualities to its predecessors but the production version was modified to make extensive use of components from the F.3, in order to ease production, giving a lower performance than either the F.2A or F.3.[citation needed]

Operational history

The F.5 did not enter service until after the end of the First World War, but replaced the earlier Felixstowe boats (together with the Curtiss machines), to serve as the Royal Air Force 's (RAF) standard flying boat until being replaced by the Supermarine Southampton in 1925.[citation needed]

Variants

- N90

- N90 was the air ministry serial of the prototype Felixstowe F.5 built by the Seaplane Experimental Station.

- Felixstowe F.5

- Main production variant built by sub-contractors, differed from prototype in the use of Felixstowe F.3 components to ease manufacture.

- Felixstowe F5L

- American-built version of the F.5 with two Liberty engines; 137 built by the Naval Aircraft Factory (USA), 60 by Curtiss Aviation (USA) and 30 by Canadian Aeroplanes Limited (Canada).[citation needed]

- Gosport Flying Boat

F.5 of the Gosport Aircraft Company at Calshot, eighth of a batch of 50 ordered.[2]

F.5 of the Gosport Aircraft Company at Calshot, eighth of a batch of 50 ordered.[2]- One of the ten RAF aircraft built by the Gosport Aircraft Company was civil registered as a Gosport Flying Boat in 1919 to appear at the First Air Traffic Exhibition at Amsterdam in August 1919.[3]

- Gosport Fire Fighter

- Proposed 10-seat version of the F.5 designed to carry men and material to the scene of a forest fire or emergency.[4][5]

- Gosport G5

- Proposed civilian version of the F.5 for two crew and six passengers, mail and cargo or either alone, fitted with two 365 hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII, 450 hp Napier Lion or 500 hp Cosmos Jupiter engines. As the Fire Fighter above, the G5 could be adapted to operate in remote areas for locating forest fires and transporting personnel and fire-fighting equipment.[5][6]

- Gosport G5a

- Proposed smaller variant of the G5 with a 97 ft 6in span and 46 ft in length, for two crew and six passengers with an increased loading capacity.[5][6]

- Aeromarine 75

- American civilian version of the Felixstowe F5L, eight converted by the Aeromarine Plane and Motor Company for three crew, 10–14 passengers and mail, fitted with two Liberty 12A engines. Entered service 1 November 1920.[7][8][9] The first in-flight movie screened in an Aeromarine 75 during the Pageant of Progress Exposition, Chicago , August 1921.

- Navy F.5

- An improved Japanese version of the F.5 known as the Navy F.5 used by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) between 1922 and 1930. The Hiro Naval Arsenal first licence-built the Felixstowe F.5 from October 1921, Aichi continued manufacture until 1929.[10]

- Saunders hull

- S. E. Saunders were awarded a contract in 1922 to investigate the merits of a tunnel type wooden hull in comparison with an all-metal hull built by Short Brothers.[citation needed]

- The new 'hollow bottom' ventilated hull was patented by Saunders and fitted to F.5 (N178), the aircraft delivered to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment in September 1924, however trials were brief and it was dismantled and scrapped by mid 1925. The Short Brothers' design proved the merit of metal hulls.[citation needed]

- Short S.2

- In 1924 the Air Ministry invited tenders for two hulls of modern design to suit the wings and tail surfaces of the F.5. Short Brothers submitted a proposal for an all-metal hull developed from the Short Silver Streak.[citation needed]

- Built of duralumin, then a largely untried and untrusted material, the aircraft was first flown on 5 January 1925 and delivered to the Marine Aircraft Experimental Establishment at Felixstowe on 14 March where it was subjected to a series of strenuous tests, including dropping the aircraft onto the water by stalling it at a height of 30 ft (9 m): the aircraft withstood all trials, and after a year an inspection revealed only negligible corrosion.[citation needed]

- Thereafter, all Short flying boats were of metal construction and other manufacturers pursued the same practice following development of their own construction methods. The trials succeeded in overcoming official resistance to the use of duralumin, and led to the order for the prototype Short Singapore[11] (N179).

- Hiro H1H

- Hiro Naval Arsenal produced their own variant of the Navy F.5, as the H1H. The first version, Navy Type 15 with a wooden hull was powered by either Lorraine W-12 or BMW VII engines, the Type 15-1 had a longer wing span, whilst the Type 15-2 had an all-metal hull and four-bladed propellers. It was retired in 1938.[12][13]

- Atlantic Coast Airways F5L

- American civil version of the ex-U.S. Navy Felixstowe F5L, converted for the Atlantic Coast Airway Corporation of Delaware; reported to accommodate 25 passengers for the inaugural flight 26 August 1928. Fitted with Hamilton, two-bladed aluminium alloy propellers[14][15][16][17]

Operators

![]() United Kingdom

United Kingdom

- Royal Air Force – generally formed from RNAS flights.

- No. 230 Squadron RAF

- No. 231 Squadron RAF

- No. 232 Squadron RAF

- No. 238 Squadron RAF

- No. 247 Squadron RAF

- No. 249 Squadron RAF

- No. 259 Squadron RAF

- No. 261 Squadron RAF

- No. 267 Squadron RAF

- Gosport Aircraft and Engineering Company – one civil registered F.5.

![]() United States

United States

- United States Navy

- Aeromarine Airways

- Atlantic Coast Airways Corporation of Delaware

![]() Japan – (Post-war)

Japan – (Post-war)

- Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service – licence built by the Hiro Naval Arsenal and Aichi.

Specifications (F.5)

Data from Aircraft of the Royal Air Force[18]

General characteristics

- Crew: four

- Length: 49 ft 3 in (15 m)

- Wingspan: 103 ft 8 in (31.6 m)

- Height: 18 ft 9 in (5.7 m)

- Wing area: 1,409 sq ft (131 m2)

- Empty weight: 9,100 lb (4,128 kg)

- Gross weight: 12,682 lb (5,753 kg)

- Powerplant: 2 × Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII, V-12 , 345 hp (257 kW) each

Performance

- Maximum speed: 76 kn (88 mph, 142 km/h) at 2,000 ft (610 m)

- Endurance: Seven hours

- Service ceiling: 6,800 ft (2,073 m)

- Time to altitude: 30 min to 6,500 ft (1,980 m)

Armament

- Guns: 4 × Lewis guns (one in the nose, three amidships)

- Bombs: Up to 920 lb (417 kg) of bombs beneath wings

See also

- Sempill Mission

Related development

- Felixstowe F.2

- Felixstowe F.3

- Felixstowe F.4 Fury[6]

- Felixstowe F5L

- Short N.3 Cromarty

- Hiro H1H

- Naval Aircraft Factory PN

- Short Singapore

- Hall PH

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Phoenix P.5 Cork

- Vickers Valentia

- English Electric Kingston

- Supermarine Swan

- Supermarine Southampton

- Saunders A.14

References

Notes

- ↑ "Felixstowe F.5, N4568, in formation with another aircraft, 1928". Hendon. 1928. http://navigator.rafmuseum.org/results.do?id=111589&db=object&pageSize=1&view=detail.

- ↑ Cowin, Hugh W. (1999). Aviation Pioneers. Osprey. http://flyingmachines.ru/Site2/Crafts/Craft25636.htm. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- ↑ Jackson 1974, p. 342

- ↑ "The Gosport Flying-Boats". Flight: 1006. 31 July 1919. http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1919/1919%20-%201004.html.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bruce, 23 December 1955, p.931

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 "Some Gosport Flying Boats for 1920". Flight: 1657–1658. 25 December 1919. http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1919/1919%20-%201655.html.

- ↑ Spooner, Stanley, ed (5 August 1920). "An Aeromarine Limousine Flying Boat". Flight XII (606). https://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1920/1920%20-%200863.html?search=aeromarine.

- ↑ Johnston, E. R. (2009). "Part 1: The Early Era, 1912–1928". American Flying Boats and Amphibious Aircraft: An Illustrated History (illustrated ed.). McFarland. p. 11. ISBN 978-0786439744. https://books.google.com/books?id=H1EIAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA11.

- ↑ Kusrow; Larson, Daniel; Björn (2017). "A Website About Aeromarine Airways A Pioneer Airline in U.S. Aviation". http://www.timetableimages.com/ttimages/aerom.htm.

- ↑ "Hiro (Hirosho) Navy Type F.5 Flying-boat.". http://japaneseaircraft.devhub.com/blog/614328-hiro-hirosho-navy-type-f5-flying-boat/.

- ↑ Barnes 1967, p. 197.

- ↑ Mikesh, Robert C.; Abe, Shorzoe (1990). Japanese Aircraft 1910–1941. Maryland 21402: Naval Institute Press Annapolis. ISBN 1-55750-563-2.

- ↑ Januszewski, Tadeusz; Zalewski, Kryzysztof (2000). Japońskie samoloty marynarski 1912-1945. tiel2, Lampart. ISBN 83-86776-00-5.

- ↑ "Travellers by Airplane to Hear Sound Pictures". San Antonio Express. 24 August 1928. https://sep.turbifycdn.com/ty/cdn/scripophily/atlanticcoastnews1.jpg.

- ↑ Larsson; Zekria, Björn; David (9 April 2004). "Atlantic Coast Airways". Airline Timetable Images. https://www.timetableimages.com/ttimages/acal.htm.

- ↑ Fortier, Rénald (3 April 2018). "The costliest sandwich shop on planet Earth, Part 1". Ingenium. https://ingeniumcanada.org/channel/articles/the-costliest-sandwich-shop-on-planet-earth-part-1.

- ↑ Fortier, Rénald (9 April 2018). "The costliest sandwich shop on planet Earth, Part 2". Ingenium. https://ingeniumcanada.org/channel/articles/the-costliest-sandwich-shop-on-planet-earth-part-2.

- ↑ Thetford 1979

- ↑ Evans; Peattie, David C.; Mark R. (2012). Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy 1887–1941 (illustrated ed.). Seaforth Publishing. pp. 179–181. ISBN 978-1-84832-159-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=iSDOAwAAQBAJ&pg=PA180.

Bibliography

- Barnes, C.H. Shorts Aircraft Since 1900. London: Putnam, 1967.

- J.M., Bruce (2 December 1955), "The Felixstowe Flying-Boats (Historic Military Aircraft No. 11 Part 1)", Flight: pp. 842–846, http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1955/1955%20-%201723.html

- J.M., Bruce (16 December 1955), "The Felixstowe Flying-Boats (Historic Military Aircraft No. 11 Part 2)", Flight: pp. 895–898, http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1955/1955%20-%201772.html

- J.M., Bruce (23 December 1955), "The Felixstowe Flying-Boats (Historic Military Aircraft No. 11 Part 3)", Flight 68 (2448): 929–932, http://www.flightglobal.com/pdfarchive/view/1955/1955%20-%201806.html

- Donald, David and Jon Lake, eds. Encyclopedia of World Military Aircraft. London: AIRtime Publishing, 1996. ISBN:1-880588-24-2.

- A.J.Jackson, British Civil Aircraft since 1919 Volume 2, Putnam & Company, London, 1974, ISBN:0-370-10010-7

- Taylor, Michael J.H., ed. Jane's Encyclopedia of Aviation. London: Studio Editions, Ltd., 1989. ISBN:0-517-10316-8.

- Thetford, Owen. Aircraft of the Royal Air Force since 1918. London: Putnam & Co., 1979. ISBN:0-370-30186-2.

External links

- First visit of an English flying boat to Kristiana: Film of the arrival and overflight by an RAF Felixstowe F.5 flying boat (N4044) at Kristiania (later Oslo), Norway, July 1919.

- Royal Air Force: Film of Fleet Air Arm aircraft and aircraft operating from shore bases, including the F.5, 1925.

- Felixstowe Flying-Boats

|