Engineering:HMS Echo (1797)

Echo

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Echo |

| Operator: | Royal Navy |

| Ordered: | 19 December 1796 |

| Builder: | Thomas King, Dover |

| Laid down: | February 1797 |

| Launched: | September 1797 |

| Commissioned: | October 1797 |

| Fate: | Sold May 1809 |

| Name: | Echo |

| Owner: | Daniel Bennett |

| Acquired: | 1809 by purchase |

| Fate: | Wrecked 1 April 1820 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type: | Echo-class brig |

| Tons burthen: | 3419⁄94,[1] or 342,[2] or 345,[3] (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 29 ft 6 in (9.0 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 10 ft 0 in (3.0 m) |

| Sail plan: | Ship-sloop |

| Complement: | 90 |

| Armament: |

|

HMS Echo, launched in 1797 at Dover, was a sloop-of-war in the Royal Navy. She served on the Jamaica station between 1799 and 1806, and there captured a small number of privateers. The Navy sold her in 1809 and she became a whaler. She made four complete whale-hunting voyages but was wrecked in the Coral Sea in April 1820 during her fifth whaling voyage.

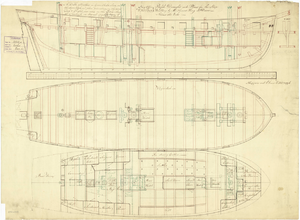

Design

Echo was the sole vessel of her class. Her designer was John Henslow, and she was identical with his contemporaneous Busy except that Echo was a ship-sloop and Busy was a brig-sloop.[1][5] Henslow's designs were in competition with a brig-sloop and a ship-sloop designed at the same time by Sir William Rule. Rule's design won as the Admiralty ultimately ordered 106 Cruizer-class brig-sloops.

Commander Graham Hammond commissioned Echo in October 1797 for the North Sea.[1]

On 23 March 1798 Echo was scouting ahead of Apollo and the rest of her squadron when Echo discovered a cutter that she immediately chased. The cutter ran ashore a few miles north of Camperdown where her crew abandoned her when boats from the ships of the squadron deployed to attempt to bring her off. Surf, and the lateness of the hour prevented the British from recovering the cutter so they destroyed her. She had been armed with 10 guns and was out of Dunkirk.[6]

Commander John Allen replaced Hammond in January 1799 and sailed Echo to the Jamaica station.[1]

Captain Edward Tyrrell Smith of Hannibal, and senior officer of a squadron patrolling off Havana, instructed Allen on 14 May to proceed to New Providence to re-provision and refill his water casks. After he had completed this, Allen sailed to stretch between the Dry Tortugas and the Colorados in an attempt to rejoin the squadron. Although Allen and Echo remained there until 3 July.[7]

On that morning Allen sighted three vessels, the largest of which seemed the most suspicious. Echo gave chase and at 7p.m. the quarry raised French colours and fired a shot. Echo caught up with her at 9p.m., and after a few shots from Echo, and a few broadsides from the French vessel, she struck. She was the letter of marque barque Amazon(e), armed with ten 6-pounder guns and carrying a crew of 60. She was sailing from Jacquemel to Bordeaux with a cargo of coffee. When Echo took her prisoners out of Amazon they proved to be quite unwell. Allen and his officers decided to put the prisoners on a Spanish sloop that Echo had taken a few days earlier and they then directed the sloop to the nearest Spanish port. Echo's sails needed a complete overhaul, and with the squadron nowhere in sight, Allen escorted Amazon to Port Royal.[7][lower-alpha 1]

At some point Commander Robert Philpot (who had been promoted to Commander on 3 January 1799), replaced Allen.[9]

Between 1 and 26 June, Echo was in company with Greyhound and Solebay. The shared in Greyhound's capture on 29 April of Virgin del Carmen, a Spanish xebec of 80 tons (bm), two guns, and 16 men. She had been sailing from Veracruz to Cadiz with a cargo of cochineal and sugar.[10][11]

The same three warships shared in the proceeds of the capture or detainment of three unarmed merchant vessels:[10]

- Spanish schooner Conception, with $111,000 on board, which had been sailing from Veracruz to Havana under the command of an ensign in the Spanish navy;

- Spanish brig Campeacheana, which had been sailing from Campeachy to Havana with log wood; and,

- Ship Adventure, under American colours, sailing from Campeachy to a market, carrying log wood and suspicious papers.

Hannibal, Thunderer, Maidstone, York, Volage, and Echo shared the proceeds of the capture or detention between 26 June and 21 July of the vessels:[12]

- Spanish schooner Nostra Senora del Carmen, sailing from Havana to Vera Cruz, carrying dry goods;

- Brig Quinty Bay Cook, under American colours, sailing from St. Thomas to Havana, carrying 97 bags of quicksilver (the captors took out the cargo and freed the vessel);

- Schooner Pegasus, under American colours, sailing from Jamaica to Havana with 68 slaves;

- Schooner Sally, under American colours, sailing from Havana to Charlestown with 72 boxes of sugar (the captors took out the cargo and freed the vessel).

Between 21 July and 27 October, Echo captured three merchant vessels:[13]

- Schooner Hawke, under American colours, which had been sailing from Baltimore to Santiago de Cuba, carrying flour;

- French Schooner Petit Victoire, sailing from Porto Rico to Saint Domingo, carrying wine and planks; and

- Schooner Mary Magdalen, under Danish colours, sailing from Cape Francoise to Saint Thomas, carrying rum and sugar.

On 14 October Philpot chased a brig into Lagnadille Bay at the north-west of Puerto Rico. There he saw other vessels also, some of them loaded. The following day he sent his pinnace and jolly boat in to see what they could cut out. The British found that they could not catch any vessels at anchor, but they were able to capture a Spanish brig laden with cocoa and indigo that she was carrying from "Camana" to "Old Spain". The brig was armed with two 4-pounders and had a crew of 20 men. The British made another sweep through the bay on the 16th. This time the brig they had first followed in two days before hailed them. She was armed with twelve 4-pounders and was moored about half a cable's length from the shore, broadside on, and flanked by two field pieces, one 18-pounder, and some smaller carriage guns on the beach. The 30 men on board were all on deck with matches lighted and guns primed. Still, when the 14 men from Echo boarded over the bow the French and Spanish crew fled below deck. The British cut the mooring cables as the guns on the beach opened fire. The fire from shore hulled the brig several times and sank the pinnace, but brig and jolly boat were soon out of range. The only loss to the British was the pinnace with her arms and ammunition; there were no casualties. The brig was an American-built French letter of marque under the command of enseigne de vaisseau Pierre Martin, who was ashore. She had a valuable cargo and was due to sail in two days for Curacoa where she was to be fitted out as a privateer.[14] She appears to have been Alliance, renamed Bonaparte in September 1799; she was probably from Saint-Malo and operated out of Guadeloupe.[15]

At some point between 27 October 1799 and 20 February 1800, Diligence detained Margaretta, a Danish schooner that had been sailing from Jacquemel to St. Thomas's with coffee and cotton had fallen prey to a Spanish privateer; Echo captured the privateer.[16]

Between 20 February and 28 May, Echo shared in only one capture, that of the Swedish brig Betsey. She was carrying coffee and sugar when Volage and Echo detained her.[17]

On 1 July 1800 Philpot was made post captain into Prompte.[9] John Serrell was made Commander into Echo, replacing Philpot. Serrell was promoted to post captain on 27 January 1803 and appointed to Garland.[18]

During the period 3 August 1800 and 3 January 1801, Echo recaptured the British ship Bellona.[19]

On 14 April Echo captured the Spanish privateer Santa Theresa.[lower-alpha 2]

Admiral Sir John Duckworth, commander-in-chief of the Jamaica station, promoted Edmund (or Edmond) Boger into Echo on 27 January 1803 to replace Serrell.[21] He also put on board a young volunteer named Samuel Roberts.[22]

On 13 October 1803 Echo and Badger captured the French schooner Fanny.[lower-alpha 3]

Roberts supposedly used one of Echo's boats, and 13 men armed only with side and small arms, to capture five vessels carrying 250 soldiers. Then one day Echo inadvertently left him behind when she sailed from Jamaica. While he was on shore he observed a French privateer capture the West Indiaman Dorothy Foster. Roberts gathered some volunteer sailors and took another merchant vessel in pursuit, recapturing Dorothy Foster.[lower-alpha 4] For this feat Boger informally made Roberts an acting lieutenant.[22]

Boger then put Roberts in command of a tender armed with one 12-pounder carronade and two 4-pounder guns, and gave him a crew of 21 men. Boger assigned Roberts to watch for Spanish vessels leaving Havana for Europe. Unfortunately for Roberts and his crew, they encountered two Spanish vessels, one of 12 guns and 60 men, and the other of eight guns and 40 men. Roberts fought for half-an-hour until his vessel sank, taking with it the British dead and wounded. The Spaniards then took him (and presumably the other survivors) prisoner.[22]

Early in 1804 Echo was escorting a convoy of nine merchant vessels through the Gulf of Florida to Jamaica. Boger learned that 2,000 French troops were about to sail from Havana for New Providence, Bahamas. The next morning Echo sighted the enemy transports with the 20-gun corvette Africaine and two 18-gun-brigs as escorts. When the corvette approached Echo and her convoy, Boger ordered his charges to close around the largest and most formidable-appearing vessel, and had her fly a pennant. The French, assuming that vessel to be a frigate, retreated. Even so, Echo was able to cut off and capture a transport with 300 troops on board. A gale on 22 April later hit the French convoy, possibly destroying it.[21]

The British believed that Africaine had been wrecked with all hands on the Charlestown bar.[21] However, the truth was less tragic and more interesting in that it gave rise to a landmark legal case. The gale had cost Africaine her mizzenmast and 16 men swept overboard, as well as six guns that the crew had thrown overboard to lighten her, but she had reached Charleston bar in the evening of 3 May. It was low tide and although a pilot from Charleston had come aboard, she had to anchor and await high tide so that she could cross. Early on 4 May, the British privateer brig Garland, William Pindar, master, accompanied by a ship, came up and after firing a shot, caused Africaine to strike. Pindar then took Africaine into Charleston as his prize. The French commercial agent in Charleston, Jean Francis Soult, sued to have the vessel freed on the grounds that the capture had taken place within the territorial waters of the United States, a neutral party. In the case Jean Francis Soult v. Corvette L'Africaine, Judge Thomas Bee of the South Carolina District Court consulted maps and heard testimony, the upshot of which was that Garland had seized Africaine more than one league (three nautical miles or 3.452 miles) offshore, and hence outside U.S. territorial waters. The case established that territorial waters were to be measured from the low-tide line from the shore, with shoals completely under water not counting for the determination of shore or coast.[25][26][27]

During early 1804 Echo recaptured the ship Mary Ann.[28]

Echo delivered some dispatches for Admiral Dacres aboard Surveillante and then Boger, per his instructions, proceeded to patrol off Curaçao. Echo had just reached Bonnaire on 30 September when she encountered a French lugger. After having endured a two-hour chase by 'Echo, the lugger's crew ran her ashore. Boger deployed his boats and they succeeded in retrieving the lugger, which turned out to be Hasard, a new, fast-sailing vessel from Guadeloupe. She was pierced for 16 guns but had only ten 4-pounder guns mounted. Her crew of 50 men was under the command of Citizen Lambart. She had been cruising for 10 days but had only captured the brig Hawk, from Trinidad. Hawk's master and two crew members were on board Hasard so Boger put them in charge of her with orders to sail her to Jamaica.[29] Hasard reached Jamaica on 15 October.

On or about 1 May 1805 the schooner Sarah Ann. which was, by agreement, acting as a tender to Echo, captured two Spanish schooners, Santa Rosa and Nostra Senora del Regla. The prize money notice also covered a parcel of Spanish grass rope, and bark landed from Echo.[30]

Between 4 and 25 January, Echo captured and sent into Jamaica Eliza Ann (sailing from St Thomas to Santo Domingo), Janet (from Caro Bay), and the American schooner Cornelia (from Curacoa).[31]

Boger was appointed captain of Brave, which HMS Donegal had captured on 6 February 1806 at the Battle of San Domingo. He was her captain when she foundered shortly thereafter on 12 April (without loss of life) while en route to Britain.[32] His promotion to post captain was dated 22 May.[21]

Echo escorted to Jamaica two vessels that had been taken and recaptured, Imperial, Galt, master, which had been sailing from Jamaica to Liverpool, and Sarah, which had been sailing from Jamaica. Atlas had recaptured them.[33]

It is not clear who replaced Boger in command of Echo.

Echo shared with Surveillante and Fortunee in the proceeds of the capture on 9 July of several merchant vessels laden with sugar.[34]

Echo shared with Surveillante, Fortunée, Superieure, and Hercule, in the proceeds of the capture on 5 July 1806 of the Spanish ship La Josepha, laden with quicksilver.[35]

Disposal: Echo sailed back to Britain with the convoy from Jamaica but parted from it off Havana. When she was slow to arrive back in England there were fears that the Spanish had captured her.[36] They had not and in October 1806 she was laid up at Deptford. The "Principal Officers and Commissioners of His Majesty's Navy" first offered "Echo...lying at Deptford" for sale on 12 January 1809.[37] The Navy sold her there on 18 May 1809.[1]

Whaler

Daniel Bennett purchased Echo and she made four complete whaling voyages for him. Echo wrecked on her fifth voyage for Daniel and his brother William.[2] Echo was mentioned in the 1809 Protection List,[3] which exempted her crewmen from impressment when she was outbound.

For her first whaling voyage Echo left Britain on 18 September 1809 and returned on 2 October 1811. Her master was Henry Rowe.[2] Lloyd's Register for 1810 gave her destination as the South Seas.[4]

Echo's master for her second whaling voyage was Joseph Whiteus (or J. Whitehouse, or Whiting). She left Britain on 23 November 1811 and returned on 12 August 1813.[2]

Echo had a new master for third whaling voyage. There are two names, Graham and Robinson, suggesting that she may have changed masters during the voyage. Echo left Britain on 7 February 1816. Echo, Graham, master, was at Rio de Janeiro on 26 April. Echo, Robinson, master, was at Deal on 9 April, and Echo, Roberton, master, arrived at Gravesendon 10 April 1818 with 150 casks.[2]

Echo left Britain on her fourth whaling voyage on 17 May 1818, with Mowatt, master, and destination South Georgia. She was reported there on 3 February 1819. She returned to Britain on 6 May with 280 casks and 250 skins.[2]

Fate

William Spence sailed Echo on her last, ill-fated voyage. She left Britain on 24 September 1819, bound for New Zealand. She was reported to have been at Bay of Islands in March 1820.[2] She was wrecked on Cato Reef, in the Coral Sea, on 1 April 1820. Her crew were rescued and they arrived at Port Jackson early in July.[38] They had taken to two boats and set out for Port Jackson. One boat under the command of the mate encountered the schooner Sinbad, Payne, master, of Port Jackson, and reached Port Jackson on 5 July. The boat under Spence's command encountered Cumberland near Moreton Island. She brought those survivors too to Port Jackson.

Notes

- ↑ Head money for the prisoners Echo took was finally paid in 1828. A first-class share was worth £74 5s 0d; a fifth-class share, that of a seaman, was worth 11s 1 1⁄4d.[8]

- ↑ Head money was paid in September 1828. A first-class share was worth £67 18s 11 1⁄4d; a fifth-class share was worth 9s 1 3⁄4d.[20]

- ↑ It is not clear what vessel Badger was.[23] The Royal Navy had no vessel by that name in commission in 1803. She may have been a tender to Echo. Boger did establish a tender for Echo, see below, and the Navy had just sold a hoy named Badger.

- ↑ This may have been Dorothea Forster, of 332 tons (bm), Ipswich-built, and launched in 1801. Her master was W. Black and later R. Alison, her owner Fletcher & Co., and her trade London-Jamaica.[24]

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Winfield (2008), p. 264.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 British Southern Whale Fishery Database – voyages: Voyages: Echo.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Clayton 2014, pp. 108–9.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lloyd's Register (1820, Seq. No. E45.

- ↑ Winfield (2008), p. 282.

- ↑ No. 15002. 27 March 1798. p. 262. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15002/page/262

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 No. 15183. 27 March 1798. p. 944. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15183/page/944

- ↑ No. 18501. 2 September 1828. p. 1656. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/18501/page/1656

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Marshall (1824), pp. 289–90.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 No. 15184. 17 September 1799. p. 955. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15184/page/955

- ↑ No. 15326. 6 January 1801. p. 43. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15326/page/43

- ↑ No. 15192. 8 October 1799. p. 1030. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15192/page/1030

- ↑ No. 15222. 14 January 1800. p. 48. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15222/page/48

- ↑ No. 15222. 14 January 1800. p. 45. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15222/page/45

- ↑ Demerliac (1999), p. 320, No. 2734.

- ↑ No. 15253. 29 April 1800. pp. 419–420. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15253/page/419

- ↑ No. 15277. 19 July 1800. p. 826. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15277/page/826

- ↑ Marshall (1825), p. 747.

- ↑ No. 15365. 12 May 1801. p. 535. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15365/page/535

- ↑ No. 18508. 26 September 1828. p. 1774. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/18508/page/1774

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Marshall (1827), pp. 155–6.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Marshall (1830), pp. 28–29.

- ↑ No. 15670. 28 January 1804. p. 133. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15670/page/133

- ↑ Lloyd's Register (1804), No. D318.

- ↑ Bee & Hopkinson (1810), pp. 204–8.

- ↑ Founders online: To James Madison from Louis-André Pichon, 18 May 1804

- ↑ Founders online: To James Madison from James Simons, 8 May 1804 (Abstract).

- ↑ No. 15722. 24 July 1804. p. 898. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15722/page/898

- ↑ No. 15770. 8 January 1805. p. 52. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/15770/page/52

- ↑ No. 16278. 22 July 1809. p. 1162. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/16278/page/1162

- ↑ Lloyd's List No. 4036. Accessed 28 August 2016.

- ↑ Marshall (1823), pp. 594–5.

- ↑ "The Marine List". Lloyd's List (4061). 1 July 1806.

- ↑ No. 16136. 12 April 1808. p. 523. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/16136/page/523

- ↑ No. 16053. 4 August 1807. p. 1034. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/16053/page/1034

- ↑ "QUEBEC FLEET". Caledonian Mercury (Edinburgh, Scotland), 30 August 1806; Issue 13207.

- ↑ No. 16214. 31 December 1808. p. 6. https://www.thegazette.co.uk/London/issue/16214/page/6

- ↑ Lloyd's List No. 5566.

References

- Bee, Thomas; Hopkinson, Francis (1810). Reports of Cases Adjudged in the District Court of South Carolina. [1792-1809]. William P. Farrand and Company Fry and Krammerer, printers. https://books.google.com/books?id=Plg9AAAAIAAJ.

- Clayton, Jane M. (2014). Ships employed in the South Sea Whale Fishery from Britain: 1775-1815: An alphabetical list of ships. Jane M Clayton. ISBN 978-1-908616-52-4. OCLC 881129097. https://books.google.com/books?id=tzMzAwAAQBAJ.

- Demerliac, Alain (1999) (in fr). La Marine de la Révolution: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1792 A 1799. Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-906381-24-1.

- Winfield, Rif (2008). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth. ISBN 978-1-86176-246-7.

External links

[ ⚑ ] 23°S 156°E / 23°S 156°E

|