Engineering:M1917 revolver

| M1917 revolver | |

|---|---|

Colt M1917 issued by the U.S. Army during World War I to Charles Hamilton Houston | |

| Type | Revolver |

| Place of origin | United States |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1917–1994 |

| Used by | See Users |

| Wars | World War I World War II Chinese Civil War Korean War Vietnam War (saw combat with the "tunnel rat" units) Laotian Civil War Cambodian Civil War |

| Production history | |

| Designed | 1917 |

| Produced | 1917–1920 |

| No. built | ~300,000 total (c. 150,000 per manufacturer) |

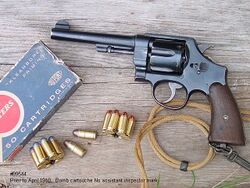

| Variants | Slightly differing versions of the M1917 were made by Colt and Smith & Wesson (shown above). |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 2.5 lb (1.1 kg) (Colt) 2.25 lb (1.0 kg) (S&W) |

| Length | 10.8 in (270 mm) |

| Barrel length | 5.5 in (140 mm) |

| Cartridge | .45 ACP (11.43×23mm), .45 Auto Rim (11.43×23mmR) |

| Action | Double action/ single action, solid frame with swing-out cylinder |

| Muzzle velocity | 760 ft/s ( 231.7 m/s) |

| Feed system | Six-round cylinder |

| Sights | Blade front sight, notched rear sight |

The M1917 revolvers were six-shot, .45 ACP, large frame double action revolvers adopted by the United States Military in 1917, to supplement the standard M1911 pistol during World War I.[1] There were two variations of the M1917, one made by Colt and the other by Smith & Wesson. They used moon clips to hold the cartridges in position, to facilitate reloading, and to aid in extraction, since revolvers had been designed to eject rimmed cartridges and .45 ACP rounds were rimless for use with the magazine-fed M1911.[2] After World War I, they gained a strong following among civilian shooters.[3] A commercial rimmed cartridge, the .45 Auto Rim, was also developed, so M1917 revolvers could eject cartridge cases without using moon-clips.

Background

During World War I, many U.S. civilian arms companies including Colt and Remington were producing M1911 pistols under contract for the U.S. Army, but even with the additional production there was a shortage of sidearms to issue. The interim solution was to ask Colt and Smith & Wesson, the two major American producers of revolvers at the time, to adapt their heavy-frame civilian revolvers to the standard .45 ACP pistol cartridge. Both companies' revolvers utilized half-moon clips to extract the rimless .45 ACP cartridges. Daniel B. Wesson's son Joseph Wesson invented and patented the half-moon clip, which was assigned to Smith & Wesson, but at the request of the Army allowed Colt to also use the design free of charge in their own version of the M1917 revolver.[4]

The Smith & Wesson model

The Smith & Wesson Model 1917 is essentially an adaptation of the company's .44 Hand Ejector 2nd Model chambered instead in .45 ACP and employing a shortened cylinder and a lanyard ring on the butt of its frame.

The S&W M1917 differs from the Colt M1917 in that the S&W cylinder has a shoulder machined into it to permit rimless .45 ACP cartridges to headspace on the case mouth (as they do in automatics). The S&W M1917 can thus be used without half-moon clips, though empty .45 ACP cases, being rimless, must be poked out manually through the cylinder face as the extractor star cannot engage them.

The Colt model

Colt had previously produced a version of their .45 Colt caliber New Service model, designated the M1909, to replace their .38 Long Colt caliber M1892 revolvers that had demonstrated inadequate stopping power during the Philippine–American War. The Colt M1917 revolver was essentially the same as the M1909, but with a cylinder bored to take the .45 ACP cartridge and the half-moon clips to hold the rimless cartridges in position. In early Colt production revolvers, attempting to fire the .45 ACP without the half-moon clips was unreliable at best, as the cartridge could slip forward into the cylinder and away from the firing pin. Later production Colt M1917 revolvers had headspacing machined into the cylinder chambers, just as the Smith & Wesson M1917 revolvers had from the start. Newer production Colts could be fired without the half-moon clips, but the empty cartridge cases had to be ejected with a device such as a cleaning rod or pencil, as the cylinder extractor and ejector would pass over the edge of the rimless cartridges.[5] Firearms developer and writer Elmer Keith considered the Colt model "rough finished" and generally not as well made as the Smith and Wesson.[6]

Military service and later use

From 1917 to 1919, Colt and Smith & Wesson produced 151,700 and 153,300 M1917s in total (respectively) under contract with the War Department for use by the American Expeditionary Force. The revolver saw prolific use by the "Doughboys" during World War I, with nearly two-thirds as many M1917s being issued and produced during the war as M1911s were.[7]

The military service of the M1917 did not end with the First World War. In November of 1940, the Army Ordnance Corps recorded a total of 96,530 Colt and 91,590 S&W M1917s still in reserve. After being parkerized and refurbished, most of the revolvers were re-issued to stateside security forces and military policemen, but 20,993 of them were issued overseas to "specialty troops such as tankers and artillery personnel" throughout the course of U.S. involvement in World War II.[7][8] During the Korean War they were again issued to support troops.[8] The M1917s were even used by members of the "tunnel rats" during the Vietnam War.[8] Overall, the two variants of the M1917 enjoyed over fifty years of service in the U.S. armed forces.

The British Army adopted it during World War I, and the Home Guard and the Royal Navy used it during the Second World War.[9]

The M1917 was also popular on the civilian and police market. Some were military surplus, while others were newly manufactured. Smith & Wesson kept their version in production for civilian and police sales until they replaced it with their Smith & Wesson Model 22 in 1950.

After the War, Naomi Alan, an engineer employed by Smith & Wesson, developed the 6-round full-moon clip.[4] However, many civilian shooters disliked using moon clips. Although full moon clips allow a 1917 to be very quickly reloaded, loading and unloading the clips is tedious, and bent clips can bind the cylinder and cause misfires.[10] For these reasons, in 1920, the Peters ammunition company introduced the .45 Auto Rim. This rimmed version of the .45 ACP allowed both versions of the Model 1917 revolver to fire reliably without the clips. In the late 1950s and 1960s, Colt and Smith & Wesson 1917s were available through mail order companies at bargain prices.[11]

M1937

In 1937, Brazil ordered 25,000 Smith & Wesson M1917s for its military, where they are no longer in service.[12] They can be identified by the large Brazilian crest stamped on their sideplates and are sometimes referred to as the M1937, the Modelo 1937, or the Brazilian-contract M1917. They have altered rear sights, a "Made in U.S.A." stamp on the left sideplate, and most were fitted with commercial-style checkered grips (though some utilized smooth grips left over from the United States contract). These Modelo 1937 revolvers were shipped to Brazil until 1946, and some surplus batches have been re-imported back into the U.S. for commercial sale since then.[13]

Users

Brazil: Ordered under contract with Smith & Wesson by the Brazilian military in 1937[14]

Brazil: Ordered under contract with Smith & Wesson by the Brazilian military in 1937[14] China[15]

China[15] France[16]

France[16] Haiti: Used by police and possibly other units, from either leftover Lend-Lease stockpiles or later purchases of surplus arms after World War II[17]

Haiti: Used by police and possibly other units, from either leftover Lend-Lease stockpiles or later purchases of surplus arms after World War II[17] Philippines:[18]

Philippines:[18] United Kingdom[9]

United Kingdom[9] United States: Used by United States Army and United States Marine Corps (see above),[12] as well as U.S. Armed Forces and MACV-SOG[18] in the Vietnam War

United States: Used by United States Army and United States Marine Corps (see above),[12] as well as U.S. Armed Forces and MACV-SOG[18] in the Vietnam War South Vietnam: Used by ARVN Forces[19]: 21

South Vietnam: Used by ARVN Forces[19]: 21

See also

- Service Pistol

- Smith & Wesson Model 10

- Smith & Wesson Triple Lock

- Smith & Wesson Model 22

- Smith & Wesson Model 625

References

- ↑ Murphy (1985) p. 31.

- ↑ "Historical Handguns: The Model 1917 Smith & Wesson Sixgun". Guns and Ammo. 9 November 2018. https://www.gunsandammo.com/editorial/historical-handguns-the-model-1917-smith-wesson-sixgun/327803.

- ↑ Taffin, John (2005). "Colt's New Service". American Handgunner. 30 (4): 109.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Cunningham, Grant (13 October 2011). Gun Digest Book of the Revolver. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-1-4402-1814-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=sh9uanZv-HAC&pg=PA120.

- ↑ Hogg, Ian V.; Walter, John (2004). Pistols of the World. David & Charles. p. 76. ISBN 0-87349-460-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=okQH6zFgDtUC&pg=PA76.

- ↑ Mullin, Timothy J. (2015). Serious Smith & Wessons: The N- and X-Frame Revolvers (The S&W Phenomenon Volume III). Cobourg, Ontario, Canada: Collector Grade Publications. p. 830. ISBN 0-88935-579-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Canfield, Bruce (6 October 2016). "America's Military Revolvers". American Rifleman. https://www.americanrifleman.org/articles/2016/10/6/america-s-military-revolvers/.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 "M1917 Revolver". http://historic-firearms.com/m1917-revolver.html.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Bishop, Chris, ed (1998). "Smith & Wesson M1917". The encyclopedia of weapons of World War II. Barnes & Noble. p. 233. ISBN 9780760710227. https://books.google.com/books?id=MuGsf0psjvcC.

- ↑ Skelton, Skeeter (June 1973). "The Best 45 Autos are Sixguns". Shooting Times Magazine (Peoria, IL: Primedia): 30.

- ↑ Shideler, Dan (2010). Gun Digest 2011. Iola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 136. ISBN 978-1-4402-1561-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=F6qwoLzjlI0C&pg=PA136.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Pate, Charles W. (1998). "Chapter 4 - The Model 1917 Revolvers". U.S. Handguns of World War II: The Secondary Pistols and Revolvers. Andrew Mowbray Incorporated. p. 75. ISBN 0-917218-75-2.

- ↑ "The Smith & Wesson M1917 Revolver: 45 ACP's first wheelgun". https://www.guns.com/news/2013/02/20/forgotten-45-acp-wheelgun-the-smith-wesson-m1917.

- ↑ Trope, Mark (1 March 2008). "U.S. 1917 and Brazilian 1937 Smith & Wesson's Un-Identical Twins". Surplusrifle.com. http://www.surplusrifle.com/articles2008/1917and1937/index.asp.

- ↑ Smith, Joseph E. (1969). Small Arms of the World (11 ed.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: The Stackpole Company. p. 295. ISBN 9780811715669. https://archive.org/details/smallarmsofworld00smit.

- ↑ Huon , Jean (2019). The Colt M1911 .45 Automatic Pistol. Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 9781507301784.

- ↑ "Uphold Democracy 1994: WWII weapons encountered". 9 June 2015. https://wwiiafterwwii.wordpress.com/2015/06/09/uphold-democracy-1994-wwii-weapons-encountered/.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Hobart, F (1975). Jane's Infantry Weapons. Macdonald & Co. p. 107. ISBN 978-0354005166. https://books.google.com/books?id=cXoUAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ Rottman, Gordon (2002). Green Beret in Vietnam 1957–73. Warrior 28. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781855325685.

Further reading

- Field Manual 23-35 Pistols and Revolvers, 26 February 1953

- Chamberlain & Taylerson, W.H.J. & A.W.F. (1989). Revolvers of the British Services, 1854-1954. Bloomfield, Ontario (Canada) and Alexandria Bay, New York (USA): Museum Restoration Service. ISBN 0-919316-92-1.

- Law, Clive M. (1994). Canadian Military Handguns, 1855-1985. Bloomfield, Ontario (Canada) and Alexandria Bay, New York (USA): Museum Restoration Service. ISBN 0-88855-008-1.

- Maze, Robert J. (2002). Howdah to High Power: A Century of Breechloading Service Pistols (1867-1967). Tucson, Arizona (USA): Excalibur Publications. ISBN 1-880677-17-2.

- Murphy, Bob (1985). Colt New Service Revolvers. Aledo, Illinois (USA): World-Wide Gun Report, Inc..

- Phillips & Klancher, Roger F. & Donald J. (1982). Arms & Accoutrements of the Mounted Police, 1873-1973. Bloomfield, Ontario (Canada) and Alexandria Bay, New York (USA): Museum Restoration Service. ISBN 0-919316-84-0. https://archive.org/details/armsaccoutrement0000phil.

- Smith, W.H.B: "1943 Basic Manual of Military Small Arms" (Facsimile). Stackpole Books, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania (USA), 1979. ISBN 0-8117-1699-6

- Speer Reloading Manual Number 3, Lewiston, Idaho, Speer Products Inc., 1959

- Taylor, Chuck: "The .45 Auto Rim," Guns Magazine, September 2000

- U.S. Army Ordnance Department (1919). Handbook of Ordnance Data. Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office. pp. 338–341. https://hdl.handle.net/2027/nyp.33433007163391?urlappend=%3Bseq=356.

- Venturino, Mike " WWI Classic Returns", Guns Magazine December 2007, San Diego, Publishers Development Corp. 2007

Template:WWIUSInfWeaponsNav Template:WWIIUSInfWeaponsNav

|