Engineering:Madre de Deus

Model of the Portuguese carrack Madre de Deus, in the Maritime Museum (Lisbon)

Script error: The function "infobox_ship_career" does not exist. | |

| General characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Class and type: | Carrack |

| Displacement: | 1600 tons |

| Tons burthen: | 900 tons |

| Length: | 30.48 m (100 ft) keel, 50.29 m (165 ft) (beakhead to stern)[1] |

| Beam: | 14.27 metres (46 ft 10 in) |

| Draught: | 9.45 m (31 ft)[lower-greek 1] |

| Sail plan: | Full-rigged, main mast is 36.88 m (121 ft) high |

| Complement: | 600–700 men |

| Armament: | At least 32 guns |

Madre de Deus (Mother of God; also called Mãe de Deus and Madre de Dios, referring to Mary) was a Portuguese ocean-going carrack, renowned for her capacious cargo and provisions for long voyages. She was returning from her second voyage East under Captain Fernão de Mendonça Furtado when she was captured by the English during the Battle of Flores in 1592 during the Anglo–Spanish War. Her subsequent capture stoked the English appetite for trade with the Far East, then a Portuguese monopoly.

Description

Built in Lisbon in 1589, she was 50 metres (165 ft) in length, had a beam of 14 metres (47 ft), rated 1,600 tons, and could carry 900 tons of cargo.[3] She had seven decks, and her draft was 26 feet (7.9 m) at her arrival in Dartmouth. Her several decks; consisted of a main orlop, three main decks, and a forecastle and a spar deck of two floors each. The length of the keel was 100 feet (30 m), the main-mast was 121 feet (37 m), and its circumference at the partners was just over 10 feet (3.0 m). The main-yard was 106 feet (32 m) long.[4] She was armed with thirty-two guns in addition to other arms, with 600 to 700 crew members, a gilded superstructure and a hold filled with treasure.[5]: 294

Capture

In 1592, by virtue of the Iberian Union, the Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 1373 was in abeyance, and as the Anglo–Spanish War was still ongoing, Portuguese shipping was a fair target for the Royal Navy.

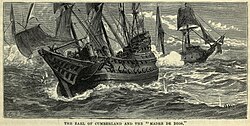

On 3 August 1592,[6] (sources vary as to the date) a six-member English naval squadron fitted out by the Earl of Cumberland and Walter Raleigh set out to the Azores to intercept Spanish shipping from the New World when a Portuguese fleet came their way near Corvo Island.[lower-greek 2] The Roebuck under John Burgh finally took her after a fierce day-long battle near Flores Island.

Among these riches were chests filled with jewels and pearls, gold and silver coins, ambergris, rolls of the highest-quality cloth, fine tapestries, 425 tons of pepper, 45 tons of cloves, 35 tons of cinnamon, 3 tons of mace, 3 tons of nutmeg, 2.5 tons of benjamin (a highly aromatic balsamic resin used for perfumes and medicines), 25 tons of cochineal and 15 tons of ebony.[lower-greek 3]

There was also a document, printed at Macau in 1590, containing valuable information on the China and Japan trade; Hakluyt observes that it was "enclosed in a case of sweet Cedar wood, and lapped up almost an hundredfold in fine Calicut-cloth, as though it had been some incomparable jewel".

Aftermath

The carrack whilst anchored at Dartmouth was subject to theft by curious locals; it attracted all manner of traders, dealers, cutpurses, and thieves from miles around. By the time Walter Raleigh had restored order, a cargo estimated at half a million pounds (nearly half the size of England's treasury and perhaps the second-largest treasure ever after the Ransom of Atahualpa) had been reduced to £140,000.

See also

- The Armada Service

- List of longest wooden ships

- Santa Catarina (ship), her capture by the Dutch increased VOC capital by more than 50%

- Santa Anna (1522 ship)

- São João Baptista (galleon)

- Cinco Chagas (1559)

- Djong (ship)

- Baochuan

Notes

- ↑ The draught as stated by Hakluyt is 9.45 m (31 ft) in loaded weight and 7.92 m (26 ft) after some of the cargo has been transferred, but this is manifestly absurd considering that it would be deeper or equal with 1st rate ships of the 18th–19th centuries. Jordan noted a supposed frigate named Madre de Deus with 5.12 m (16.8 ft) draught, he noted that this ship's depth is unusually deeper when compared with other frigates and might be an error in transcription.[2]

- ↑ The Gulf Stream and the Westerlies converge near the Azores, where ships coming from both areas would pass.

- ↑ An inventory was taken, and the report produced mentions "Gods great favor towards our nation, who by putting this purchase into our hands hath manifestly discovered those secret trades & Indian riches, which hitherto lay strangely hidden, and cunningly concealed from us". It also speaks of the following goods aboard, besides jewels: "spices, drugs, silks, calicos, quilts, carpets and colors, &c. The spices were pepper, cloves, maces, nutmegs, cinnamon, greene, ginger: the drugs were benjamin, frankincense, galingale, mirabilis, aloes zocotrina, camphire: the silks, damasks, taffatas, scarceness, alto bassos, that is, counterfeit, cloth of gold, unwrought China silk, sleeved silk, white twisted silk, curled cypresse. The calicos were book-calicos, calico-launes, broad white calicos, fine starched calicoes, course white calicos, brown broad calicos, brown course calicos. There were also canopies, and course diapertowels, quilts of course sarcenet and of calico, carpets like those of Turkey; whereunto are to be added the pearl, muske, civet, and amber-griece. The rest of the wares were many in number, but less in value; as elephants teeth, porcelain vessels of China, coco-nuts, hides, ebenwood as black as jet, bested of the same, cloth of the rind’s of trees very strange for the matter, and artificial in workmanship".[7]

References

- ↑ Hakluyt, Richard (1904) (in en). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques & Discoveries of the English Nation Made by Sea or Over-land to the Remote and Farthest Distant Quarters of the Earth at Any Time within the Compasse of these 1600 Yeeres. 7. Glasgow: J. MacLehose and Sons. pp. 116–117. https://archive.org/details/principalnavigat07hakl/page/104/mode/2up?q=madre.

- ↑ Jordan, Brian (2001). "Wrecked ships and ruined empires: an interpretation of the Santo António de Tanna's hull remains using archaeological and historical data" (in en). International Symposium on Archaeology of Medieval and Modern Ships of Iberian-Atlantic Tradition: 301–316. https://www.academia.edu/2172023. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

- ↑ Smith, Roger (1986). "Early Modern Ship-types, 1450–1650". The Newberry Library. http://www.newberry.org/smith/slidesets/ss06.html.

- ↑ Hakluyt, Richard (1598). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques and Discoveries of the English Nation. p. 570. https://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.03.0070%3Anarrative%3D570.

- ↑ Whymper, Frederick (1877). The Sea: Its Stirring Story of Adventure, Peril, & Heroism. Volume 1 and 2. London, Paris, & New York: Cassell Petter & Galpin. https://archive.org/details/seaitsstirringst12whymrich/page/n10/mode/1up.

- ↑ Raleigh, Walter (1999). Latham, Agnes Mary Christabel. ed. The letters of Sir Walter Raleigh. Exeter: University of Exeter Press. p. 78. ISBN 978-0-85989-527-9. OCLC 42039468.

- ↑ Kessel, Elsje van (July 2020). "The inventories of the Madre de Deus: Tracing Asian material culture in early modern England" (in en). Journal of the History of Collections (Oxford University Press) 32 (2): 207–223. doi:10.1093/jhc/fhz015. ISSN 0954-6650. https://academic.oup.com/jhc/article-abstract/32/2/207/5479429. Retrieved 2022-04-09.

Further reading

- Landes, David Saul (1999). The Wealth and Poverty of Nations. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-31888-5.

- Puga, Rogério Miguel (December 2002). "The Presence of the "Portugals" in Macau and Japan in Richard Hakluyt's Navigations" (in en). Bulletin of Portuguese/Japanese Studies 5: 81–116. ISSN 0874-8438. https://redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36100506. Retrieved 2022-03-26.

|