Engineering:New York (1837 steamboat)

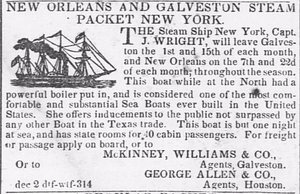

Advertisement for the steamboat New York. Telegraph and Texas Register, 2 March 1842 (Via the Portal to Texas History)

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | New York |

| Owner: | John Haggerty and Charles Morgan (1837); John Haggerty, Charles Morgan, and John T. Wright (1838)[1] |

| Operator: | Captain J. T. Wright, Captain John D. Phillips |

| Port of registry: | New York City, number 340 |

| Route: | New York and Charleston; New Orleans and Galveston |

| Completed: | 1837 |

| Fate: | Destroyed in a hurricane, Gulf of Mexico, 7 September 1846 |

| General characteristics | |

| Tonnage: | 365 |

| Length: | About 160.5 ft (48.9 m) |

| Beam: | About 22.5 ft (6.9 m) |

| Installed power: | James Watt-type steam engine |

| Propulsion: | Steam-powered sidewheeler |

| Sail plan: | Auxiliary sail |

New York is a former steamship built in 1837 for the New York and Charleston Steam Packet Company, a partnership started by James P. Allaire, John Haggerty, and Charles Morgan. Originally put into packet service between New York City and Charleston, South Carolina, New York later served ports in along the Gulf of Mexico. New York was destroyed in the Gulf of Mexico by a hurricane on 7 September 1846.

New York–Charleston packet

New York started running packet service for the New York and Charleston Steam Packet Company in 1837. As a ship of the line, it traveled between New York City and Charleston, South Carolina on a regular schedule. Shortly later though, a reorganization was triggered by the sinking of the steamship Home, which resulted in a buyout of the other partners’ shares of the New York by Charles Morgan and John Haggerty. With Morgan acting as the managing partner, this was the start of the Charles Morgan Line.[2][3]

New Orleans–Galveston packet

Morgan dispatched the New York to the Gulf of Mexico, and when it arrived in New Orleans early in 1839, he placed it under the management of the agency, Bogart & Hawthorn.[4] New York replaced the Columbia on the New Orleans and Texas Line, a cartel established between Morgan and the owners of the Cuba, another steam packet running between New Orleans and Galveston, Texas. The two companies coordinated freight, rates, and scheduling.[5] This arrangement went on hiatus during the summer as Morgan sent the New York back to New York City for refitting, but returned to the Gulf of Mexico in time for the busy fall season.[4]

Starting in January 1840, New York was the only ship of the line between New Orleans and Galveston.[6] In a letter from November 1840, Mary Austin Holley provided some descriptions and characterizations of New York's cabin, such as the "luxurious couch" that prompted her to "think of nothing but Cleopatra." The drapes were "blue satin and dimity" and the mahogany finishes were "polished like the finest pianos." The dining table featured engraved silverware and cutlery with ivory handles, and was illuminated by hand-painted lamps.[7]

Morgan sold Columbia to Henry Windle, effectively creating a new competitor on the route. Neptune, owned by Captain Pennoyer, also competed for patronage on the route. New York continued running this route until being pulled back on 25 June 1841 due to diminished demand, but returned to service in the fall. This seasonal service pattern persisted for New York through 1845. In October 1845, agents advertised a $15 passenger ticket for cabin-class.[6]

Lost at sea

On 5 September 1846, New York cast off from Galveston bound for New Orleans. The same evening, the ship sailed into a hurricane. The captain, John D. Phillips, tried to ride out the storm under anchor. In the early hours of the 7th, strong winds pulled New York off its anchorage and out to sea. A few hours later the ship started leaking before heavy winds took the promenade deck away. Of the 53 people on board, 17 drowned and 36 held onto flotsam until they were rescued by the steamship Galveston. In addition to the loss of life, as much as $40,000 in precious metals and cash went down with the ship.[3]

Discovery of the wreck

In 1990, an unnamed amateur diver from Louisiana found the wreck of the New York using a fish-finding sonar machine, a LORAN navigational device, and data gathered from a wide network of Gulf shrimpers. A team of divers found a large part of the hull and a few artifacts. These included an 1827 gold coin, two 1843 U.S. fifty-cent pieces, and a mortising machine from an 1836 patent. Archaeological dives sponsored by the Minerals Management Service (MMS) in 1997 and 1998 brought scientific expertise to bear on the site. The teams scanned the ocean floor with a magnetometer and mapped the wreckage. They discovered important engine parts, including the air pump, cam, condenser, and main piston cylinder. A paddlewheel shaft was deposited in the sand about 1,500 ft (460 m) away. There were enough engine parts for experts to identify this wreckage as that of the 1837 steamship New York.[3]

References

- ↑ James P. Baughman (1968). Charles Morgan and the Development of Southern Transportation. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. p. 251. https://archive.org/details/charlesmorgandev0000baug.

- ↑ Baughman (1968), pp. 15–19.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Jack B. Irion and David A. Ball. "The New York and the Josephine: Two Steamships of the Charles Morgan Line". Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. https://www.boem.gov/uploadedFiles/BOEM/Environmental_Stewardship/Archaeology/Irion_and_Ball.pdf.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Baughman (1968), p. 32–33.

- ↑ Baughman (1968), pp. 22–28.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Baughman (1968), pp. 35–39.

- ↑ Hogan, William Ransom (1946). The Texas Republic: A Social & Economic History. Austin: Texas State Historical Association. p. 8.