Engineering:Pantometrum Kircherianum

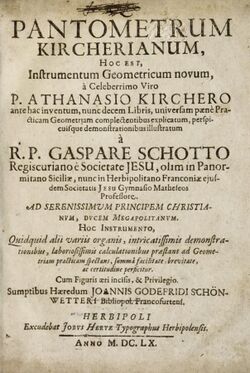

Pantometrum Kircherianum is a 1660 work by the Jesuit scholars Gaspar Schott and Athanasius Kircher. It was dedicated to Christian Louis I, Duke of Mecklenburg and printed in Würzburg by Johann Gottfried Schönwetter.[1] It was a description, with building instructions, of a measuring device called the pantometer, that Kircher had developed some years before.[2] The first edition include 32 copperplate illustrations.[3]

Description of the pantometer

The name "pantometer" derives from Greek, in which "pan" means "all" and "metron" means "measure" - indicating that this instrument can be used to measure anything. As described in the book, it consisted of a square frame, a dioptra, and a disc that fitted within the square. The disc contained a built-in compass and a space for putting a sheet of paper. The disc could turn freely within the square, or be locked in a fixed position. Mounted on this apparatus was a movable ruler parallel to the edge of the square on which the dioptra was attached. An illustration in the book showed how the device could be used to measure the distance of objects by triangulating from two different points on a baseline.

The introduction to the book emphasised both the accuracy of the device and its ease of use,[4] and stated that it could be used to "measure all, witness latitudes, longitudes, altitudes, depths and surfaces, terrestrial and celestial bodies, and whatever indeed we are accustomed to doing with other instruments."[5]

Kircher's development of the pantometer

Kircher had mentioned the pantometer in his Specula Melitensis Encyclica noting that it was designed to help the Knights Hospitaller to solve "the most important mathematical and physical problems."[2][6] It was a surveying tool that resembled a draughts board and could be used to calculate distances, weights and dimensions. In Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica (1643) Kircher has described an "Instrumentum, Pantometrum, Ichnographicum Magneticum" which allowed all things to be measured. It was 'magnetic' because it incorporated a compass, and 'ichnographic' because it could be used in map-making.[4]

According to Schott, Kircher had first conceived of it in the company of father Ziegler, perhaps as early as 1623. Schott has been with Kircher in 1631 when he had first assembled the instrument and named it the 'pantometrum', sending an early example to Holy Roman Emperor Frederick III. [7] Kircher had certainly used the pantometer himself to take scientific measurements when he was lowered into the crater of Vesuvius in 1638.[6]

Later editions and references

Pantometrum Kircherianum was reprinted by Cholinus in Frankfurt in 1668[8] and again in 1669.[9] The work was referenced in books by a number of later writers, including Jacob Leupold's Theatrum Arithmetico-Geometricum (1727) and Christian Wolff's Mathematisches Lexikon (1747).[4]

External links

- digital copy of Pantometrum Kircherianum at the Max Planck Institute Library

- digital copy of Pantometrum Kircherianum at the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

See also

References

- ↑ Pantometrum Kircherianum, hoc est, instrumentum geometricum novum, à celeberrimo viro P. Athanasio Kirchero ante hac inventum, : nunc decem libris, universam paenè practicam geometriam complectentibus explicatum, perspicuisque demonstrationibus illustratum. OCLC 6605090. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/6605090. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Westfall, Richard S.. "Kircher, Athanasius". The Galileo Project, Rice University. http://galileo.rice.edu/Catalog/NewFiles/kircher.html. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ "Pantometrum Kircherianum". https://www.abebooks.co.uk/first-edition/Pantometrum-Kircherianum-Hoc-Instrumentum-Geometricum-novum/30263215250/bd. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Horst Beinlich (2002). Spurensuche: Wege zu Athanasius Kircher. Verlag J.H. Röll. pp. 119–136. ISBN 978-3-89754-213-6. http://www.history.didaktik.mathematik.uni-wuerzburg.de/vollrath/papers/090.pdf. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ↑ Sean Cocco (29 November 2012). Watching Vesuvius: A History of Science and Culture in Early Modern Italy. University of Chicago Press. p. 142. ISBN 978-0-226-92373-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=XcCOiOBv9_MC&pg=PA271. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 John Edward Fletcher (25 August 2011). A Study of the Life and Works of Athanasius Kircher, 'Germanus Incredibilis': With a Selection of His Unpublished Correspondence and an Annotated Translation of His Autobiography.. BRILL. pp. 22, 38, 163. ISBN 978-90-04-20712-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=7Wo-w2sl6zEC&pg=PA163. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ Thomas L. Hankins; Robert J. Silverman (2014-07-14). Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton University Press. p. 333. ISBN 978-1-4008-6411-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=bUoABAAAQBAJ&pg=PA333. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- ↑ Kircher, Athanasius; Schott, Gaspar. "Pantometrum Kircherianum, Hoc Est, Instrumentum Geometricum novum". Bayerische Staatsbibliotek. https://digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb10053122. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

- ↑ Pantometrum Kircherianum : hoc est instrumentum geometricum novum. OCLC 433835736. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/433835736. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

|