Engineering:Porta-Color

General Electric's Porta-Color was the first "portable" color television introduced in the United States in 1966.

The Porta-Color set introduced a new variation of the shadow mask display tube. It had the electron guns arranged in an in-line configuration, rather than RCA's delta arrangement. The main benefit of the in-line gun arrangement is that it simplified the convergence process, and did not become easily misaligned when moved, thus making true portability possible. There were many variations of this set produced from its introduction in 1966 until 1978, all using GE's Compactron vacuum tubes (valves).

The name has been variously written, even in GE's literature, as "Porta Color", "Porta-Color" and "Porta-color". The name may also refer to the specific television model, or less commonly, the style of television tube it used.

History

Basic television

A conventional black and white television (B&W) uses a tube that is uniformly coated with a phosphor on the inside face. When excited by high-speed electrons, the phosphor gives off light, typically white but other colors are also used in certain circumstances. An electron gun at the back of the tube provides a beam of high-speed electrons, and a set of electromagnets arranged near the gun allow the beam to be moved around the display. Time base generators are used to produce a scanning motion. The television signal is sent as a series of stripes, each one of which is displayed as a separate line on the display. The strength of the signal increases or decreases the current in the beam, producing bright or dark points on the display as the beam sweeps across the tube.

In a color display the uniform coating of white phosphor is replaced by dots or lines of three colored phosphors, producing red, green or blue light (RGB color model) when excited. When excited in the same fashion as a B&W tube, the three phosphors produce different amount of these primary colors, which mix in the human eye to produce an apparent color. To produce the same resolution as the B&W display, a color screen must have three times the resolution. This presents a problem for conventional electron guns, which cannot be focused or positioned accurately enough to hit these much smaller individual patterns.

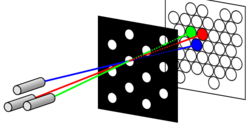

Shadow mask

The conventional solution to this problem was introduced by RCA in 1950, with their shadow mask system. The shadow mask is a thin steel sheet with small round holes cut into it, positioned so the holes lie directly above one triplet of colored phosphor dots. Three separate electron guns are individually focussed on the mask, sweeping the screen as normal. When the beams pass over one of the holes, they travel through it, and since the guns are separated by a small distance from each other at the back of the tube, each beam has a slight angle as it travels through the hole. The phosphor dots are arranged on the screen such that the beams hit only their correct phosphor.

The primary problem with the shadow mask system is that the vast majority of the beam energy, typically 85%, is lost 'lighting up' the mask as the beam passes over the opaque sections between the holes. This means that the beams must be greatly increased in power to produce acceptable brightness when they do pass through the holes.

The General Electric Porta-Color

Paul Pelczynski was the project leader in the conception and production of the General Electric Porta Color in 1966.[1]

General Electric (GE) had been working on a variety of systems that would allow them to introduce color sets that did not rely on the shadow mask patents. Through the 1950s they had put considerable effort into the Penetron concept, but were never able to make it work as a basic color television, and started looking for alternate arrangements. GE eventually improved on the basic shadow mask system with a simple change to layout.

Instead of arranging the guns, and phosphors, in a triangle, their system arranged them side by side. This meant that the phosphors did not have to be displaced from each other in two directions, only one, which allowed much-simplified convergence adjustments of the three beams, compared to the conventional delta shadow mask tube. This differed sufficiently from RCA's design to allow GE to circumvent the patents. It is important to realize that the GE 11" tube still had round mask holes and phosphor dots, not rectangular ones as in the later slot-mask tubes. The innovation here was with the in-line guns as opposed to the triad arrangement.

This change, which allowed vastly simpler convergence measures, together with the use of GE's own Compactron multi-function vacuum tubes led to reductions in size of the entire chassis. GE used the small size of their system as the primary selling feature. The original 28 pound set used an 11" tube and sold for $249, which was very inexpensive for a color set at that time. Introduced in 1966, the Porta-Color was extremely successful and led to a rush by other companies to introduce similar systems. GE continued refining this system, up until 1978, which marked the end of production of vacuum tube type television receivers.

GE produced the basic Porta-Color design well into the 1970s, even after most companies had moved to solid state designs when transistors with the required power capabilities were introduced. The Porta Color II was their attempt at a solid state version, but did not see widespread sales. The basic technology, however, was copied into GE's entire lineup as product refresh cycles allowed. By the early 1970s most companies had introduced the "slot-mask" designs, including RCA.[2]

Description

In a conventional shadow mask television design the electron guns at the back of the tube are arranged in a triangle. They are individually focused, with some difficulty, so that the three beams meet at a spot when they reach the shadow mask. The mask cuts off any unfocussed portions of the beams, which then continue through the holes towards the screen. Since the beams approach the mask at an angle, they separate again on the far side of the mask. This allows the beams to address the individual phosphor spots on the back of the screen.

GE's design modified this layout by arranging the electron guns in a side-by-side line (the "in-line gun") instead of a triangle (the "delta gun"). This meant that after they passed through the mask they separated horizontally only, hitting phosphors that were also arranged side by side. Otherwise, the GE design retained the round dot structure.

Later, Sony changed the whole game, replacing the shadow mask with an aperture grille and the phosphor dots with vertical phosphor stripes. They cleverly implemented a single electron gun with three independent cathodes, later branded Trinitron, all of which greatly simplified convergence.

Toshiba then countered this with their slot-mask system, which was somewhat in-between the Trinitron and the original delta-mask systems. Sony attempted to stop Toshiba from producing their in-line gun system, citing patent violations, but Toshiba won this battle, and the Toshiba tube eventually became the standard in most domestic television receivers.[citation needed]

Collecting General Electric Porta Color Televisions

Over the years, the Porta Color has attracted interest as an old (dead) technology to be rescued. Once considered throw-away items, the Porta Color has become a collectible item, being the last all-vacuum tube color television made in the US.[3]

See also

Further reading

References

Notes

- ↑ Television, Early Electronic. "General Electric Porta Color". Early Television Museum. http://www.earlytelevision.org/ge_portacolor.html. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

- ↑ New TV

- ↑ Kuhn, Martin. "In Living Porta Color". Martin Kuhn. Archived from the original on 2015-09-13. https://web.archive.org/web/20150913100926/http://www.rwhirled.com/portacolor/. Retrieved 2015-10-17.

Bibliography

- "Business News", Forbes, Volume 97 (1966), pg. 122

- Bill Hartford, "Color for $200?", Popular Mechanics, November 1968, pp. 122–127, 256

- Jim Luckett, "New TV tubes lock in better color pictures", Popular Mechanics, May 1974, pp. 85–89

|