Engineering:QF 1-pounder pom-pom

| QF 1 pdr Mark I & II ("pom-pom") | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | Autocannon |

| Place of origin | United Kingdom |

| Service history | |

| In service | 1890s–1918 |

| Used by | South African Republic British Empire Khedivate of Egypt[1] German Empire Paraguay Belgium United States Finland Bolivia[2] |

| Wars | Mahdist War[3] Spanish–American War Second Boer War 1904 Paraguayan Revolution[4] Herero Wars[5] World War I Finnish Civil War Chaco War Winter War |

| Production history | |

| Designer | Hiram Maxim |

| Designed | Late 1880s |

| Manufacturer | Maxim-Nordenfelt Vickers, Sons & Maxim DWM |

| Variants | Mk I, Mk II |

| Specifications | |

| Mass | 410 pounds (186.0 kg) (gun & breech) |

| Length | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) (total) |

| Barrel length | 3 ft 7 in (1.09 m) (bore) L/29 |

| Shell | 37 x 94R Common Shell |

| Shell weight | 1 lb (0.45 kg) |

| Calibre | 37-millimetre (1.457 in) |

| Barrels | 1 |

| Action | automatic, recoil |

| Rate of fire | ~300 rpm (cyclic) |

| Muzzle velocity | 1,800 ft/s (550 m/s)[6] |

| Maximum firing range | 4,500 yards (4,110 m) (Mk I+ on field carriage)[7] |

| Filling weight | 270 grains (17 g) black powder |

The QF 1 pounder, universally known as the pom-pom due to the sound of its discharge,[8][9][10] was a 37 mm British autocannon, the first of its type in the world. It was used by several countries initially as an infantry gun and later as a light anti-aircraft gun.

History

Hiram Maxim originally designed the Pom-Pom in the late 1880s as an enlarged version of the Maxim machine gun. Its longer range necessitated exploding projectiles to judge range, which in turn dictated a shell weight of at least 400 grams (0.88 lb), as that was the lightest exploding shell allowed under the Saint Petersburg Declaration of 1868 and reaffirmed in the Hague Convention of 1899.[11]

Early versions were sold under the Maxim-Nordenfelt label, whereas versions in British service (i.e. from 1900) were labelled Vickers, Sons and Maxim (VSM) as Vickers had bought out Maxim-Nordenfelt in 1897 but they are the same gun.

Service by nation

Belgium

The Belgian Army used the gun on a high-angle field carriage mounting.[7]

Finland[12]

About 60 were built by Finnish company Ab H. Ahlberg & Co O during World War 1 for the Russian army, and when the Finnish civil war ended about half of these were still unfinished and thus remained in Finland. The White Army captured a total of 50 – 60 guns in the Civil War of 1918 . The guns used a column mount designed for naval use. It offered 360-degree traverse and about 70-degree elevation, allowing them to theoretically be used as antiaircraft-guns. The Finns managed to get over 30 of the captured guns to working order and they were used in warships and coastal artillery fortifications. Two of these guns also saw service in an armoured trains from 1918 to late 1930's. The weapon was never popular in Finnish use as it was unreliable and had quite a short range. Main reason for the short range was in 37 mm x 94R ammunition (with moderate muzzle velocity of only about 440 m/sec), which did not really have the ballistics needed for proper antiaircraft-use. The reliability of old fuses used in their high explosive shells also proved questionable. During World War 2 some of these guns were used in coastal artillery forts, where their unsuitability for anti-aircraft use became painfully obvious. However the guns proved somewhat reliable when fired with only low elevation. This was likely because shooting with low elevation did not stress their fabric ammunition belts as much as shooting with higher elevation. Their theoretical rate of fire was around 200 – 250 rounds per minute and maximum range around 4,400 meters. Finnish coastal defence decided to use them mainly as close range defence weapons of its coastal forts against surface targets and these old guns proved somewhat successful in this role. Still, since the coastal forts had rather limited number of anti-aircraft weapons, when needed these guns were also used against enemy aircraft. At least one plane was downed by such weapons; the Humaljoki Coastal Artillery Battery in Karelian Isthmus shot down a Soviet bomber with 37-mm Maxim automatic cannon in 25 of December 1939. By that time they were terribly outdated. So the last remaining 16 guns were scrapped soon after the Continuation War ended in 1944

Germany

A version was produced in Germany for both Navy and Army.[7]

In World War I, it was used in Europe as an anti-aircraft gun as the Maxim Flak M14. Four guns were used mounted on field carriages in the German South West Africa campaign in 1915, against South African forces.[13]

United Kingdom

South African War

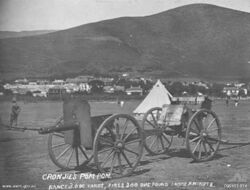

The British government initially rejected the gun but other countries bought it, including the South African Republic (Transvaal) government. In the Second Boer War, the British found themselves being fired on by the Boers with their 37 mm Maxim-Nordenfelt versions using ammunition made in Germany. The Boers' Maxim was also a large caliber, belt-fed, water-cooled machine gun that fired explosive rounds (smokeless ammunition) at 450 rounds per minute.[14]

Vickers-Maxim shipped either 57 or 50 guns out to the British Army in South Africa, with the first three arriving in time for the Battle of Paardeberg of February 1900.[15][16] These Mk I versions were mounted on typical field gun type carriages.

World War I

In World War I, it was used as an early anti-aircraft gun in the home defence of Britain. It was adapted as the Mk I*** and Mk II on high-angle pedestal mountings and deployed along London docks and on rooftops on key buildings in London, others mobile, on motor lorries at key towns in the East and Southeast of England. 25 were employed in August 1914, and 50 in February 1916.[17] A Mk II gun (now in the Imperial War Museum, London) on a Naval pedestal mounting was the first to open fire in defence of London during the war.[7] However, the shell was too small to damage the German Zeppelin airships sufficiently to bring them down.[18] The Ministry of Munitions noted in 1922: "The pom-poms were of very little value. There was no shrapnel available for them, and the shell provided for them would not burst on aeroplane fabric but fell back to earth as solid projectiles ... were of no use except at a much lower elevation than a Zeppelin attacking London was likely to keep".[19]

Lieutenant O. F. J. Hogg of No. 2 AA Section in III Corps was the first anti-aircraft gunner to shoot down an aircraft, with 75 rounds on 23 September 1914 in France.[20] The British Army did not employ it as an infantry weapon in World War I, as its shell was considered too small for use against any objects or fortifications and British doctrine relied on shrapnel fired by QF 13 pounder and 18-pounder field guns as its primary medium range anti-personnel weapon. The gun was experimentally mounted on aircraft as the lighter 1-pounder Mk III, the cancelled Vickers E.F.B.7 having been designed to carry it in its nose.[21] As a light anti-aircraft gun, it was quickly replaced by the larger QF 11⁄2 pounder and QF 2 pounder naval guns.

British ammunition

The British are reported to have initially used some common pointed shells (semi-armour piercing, with fuse in the shell base) in the Boer War, in addition to the standard common shell. The common pointed shell proved unsatisfactory, with the base fuse frequently working loose and falling out during flight.[16][22] In 1914, the cast-iron common shell and tracer were the only available rounds.[23]

United States

The U.S. Navy adopted the Maxim-Nordenfelt 37 mm 1-pounder as the 1-pounder Mark 6 before the 1898 Spanish–American War. The Mark 7, 9, 14, and 15 weapons were similar.[24] It was the first dedicated anti-aircraft (AA) gun adopted by the US Navy, specified as such on the Sampson-class destroyers launched in 1916–17. It was deployed on various types of ships during the US participation in World War I, although it was replaced as the standard AA gun on new destroyers by the 3 inch (76 mm)/23 caliber gun.

Previously, with the advent of the steel-hulled "New Navy" in 1884, some ships were equipped with the 1-pounder Hotchkiss revolving cannon.

In the aftermath of the Battle of Blair Mountain, the United States Army deployed artillery, including pompoms: "Their armament was strengthened with a howitzer and two pompoms."[25]

Rapid-firing (single shot, similar to non-automatic QF guns) 1-pounders were also used, including the Sponsell gun and eight other marks; the Mark 10 to be mounted on aircraft. Designs included Hotchkiss and Driggs-Schroeder. A semi-automatic weapon and a line throwing version were also adopted. Semi-automatic in this case meant a weapon in which the breech was opened and cartridge ejected automatically after firing, ready for manual loading of the next round.[24]

It is often difficult to determine from references whether "1-pounder RF" refers to single-shot, revolving cannon, or Maxim-Nordenfelt weapons.

Surviving examples

- A gun from 1903 at the Imperial War Museum London.[26]

- Two German-manufactured 1903 guns used during World War I are on display at the South African National Museum of Military History, Johannesburg. Nr. 542 and 543 from the Deutsche Waffen- und Munitionsfabriken.

- A German-manufactured gun in the Wehrtechnische Studiensammlung Koblenz, Germany.[27]

- A gun in Bridgton, Maine.

- An early Maxim-Nordenfelt gun, no. 2024, is currently on display the American Heritage Museum in Stow, Massachusetts.

- A gun in the Canadian War Museum.

- A gun in the Museo Naval y Maritimo Valparaiso, Chile.[28]

- A gun at the War Museum in Newport News, Va still on field mount. Flak M14

- A gun at the Royal Danish Arsenal Museum in Copenhagen, Denmark.

- A gun at Istanbul Navy Muzeum.

- 40 ItK/15 V (Vickers) in the Finnish Ilmatorjuntamuseo (Anti-Aircraft Museum) in Tuusula [29]

- A gun at Fortaleza del Cerro, Uruguay

See also

- COW 37 mm gun

- List of anti-aircraft guns

- List of infantry guns

Notes and references

- ↑ Knight, Ian, British Infantryman vs Mahdist Warrior: Sudan 1884–98: Osprey Publishing (2021)

- ↑ Huon, Jean (September 2013). "The Chaco War". Small Arms Review 17 (3). http://www.smallarmsreview.com/display.article.cfm?idarticles=1976.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of African colonial conflicts. Timothy J. Stapleton. Santa Barbara, Calif.. 2017. ISBN 978-1-59884-837-3. OCLC 950611553. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/950611553.

- ↑ "La Revolucion Paraguaya de 1904". http://www.histarmar.com.ar/ArmadasExtranjeras/Paraguay/Revolucion1904.htm.

- ↑ "THE REVOLVERKANONE AND THE MASCHINENKANONE IN THE HERERO WAR". https://www.hererowars.com/new-the-revolverkanone-and.html.

- ↑ "Handbook of the 1-PR. Q.F. Gun", 1902. Page 19, Range Table for British Mk I gun. Muzzle Velocity of 1,800 ft/second, firing 1-pound projectile with 1 oz 90 grains Cordite.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Hogg & Thurston 1972, pp. 22–23

- ↑ The Waverley pictorial dictionary (Volume SIX). London: Waverley Book Co. pp. 3335. https://archive.org/stream/waverleypictoria06wheeuoft#page/3334/mode/1up.

- ↑ "Weapons". Australian Boer War Memorial Committee. http://www.bwm.org.au/site/Weapons.asp.

- ↑ "...my paper strength will be 2,400 mounted men, 6 guns, and 8 pom-poms". Brigadier Henry Rawlinson, 2 January 1902, in South Africa. From "The Life of General Lord Rawlinson of Trent", by Sir Frederick Maurice. London: Cassell, 1928

- ↑ Hogg & Thurston 1972, p. 22, state the Hague Convention dictated the 1 lb (0.45 kg) shell; however 400 grams was set as the minimum for exploding shells by Laws of War: Declaration of St. Petersburg; 29 November 1868

- ↑ "FINNISH ARMY 1918–1945: ANTIAIRCRAFT GUNS PART 2". https://www.jaegerplatoon.net/AA_GUNS2.htm.

- ↑ Major D.D. Hall, The South African Military History Society Military History Journal – Vol 3 No 2, December 1974. "GERMAN GUNS OF WORLD WAR I IN SOUTH AFRICA". Major Hall states that these guns were made by Krupp, but the 2 captured guns in the South African Military History Museum were made by Deutsche Waffen und Munitionsfabriken (DWM)

- ↑ http://www.smallarmsreview.com/display.article.cfm?idarticles=2490, SOUTH AFRICA’S NATIONAL MUSEUM OF MILITARY HISTORY

- ↑ 'The Times History of the War in South Africa' mentions 57; Headlam 'The History of the Royal Artillery' only mentions 50.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Fiona Barbour, The South African Military History Society Military History Journal – Vol 3 No 1 June 1974. Mystery Shell

- ↑ Farndale 1988, pp. 362–363

- ↑ Routledge 1994, p. 7–8

- ↑ Official History of the Ministry of Munitions 1922, Volume X, Part 6, pp. 24–25. Facsimile reprint by Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press 2008. ISBN:1-84734-884-X

- ↑ Routledge 1994, p. 5

- ↑ "THE CANNON PIONEERS: The early development and use of aircraft cannon, by Anthony G Williams". http://www.quarryhs.co.uk/cannon_pioneers.htm.

- ↑ The British 1902 manual listed only the Common Shell as currently produced: "A number of steel shells have been issued, but no more will be provided": "Handbook of the 1-PR. Q.F. Gun", 1902. Page 18

- ↑ Treatise on Ammunition 10th Edition, 1915. War Office, UK

- ↑ Lon Savage (1990), Thunder in the Mountains: The West Virginia Mine War, 1920–21, rev. edition, Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh, Ch. 24, "'The Miners Have Withdrawn Their Lines'", p.151.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namediwm - ↑ "Bundesamt für Wehrtechnik und Beschaffung". http://www.bwb.org/portal/a/bwb/!ut/p/c4/04_SB8K8xLLM9MSSzPy8xBz9CP3I5EyrpHK9pPIkvdLUpNSi0jy9lMRiELc8NaOoJDVZvyDbUREA-WplZw!!/.

- ↑ "Cañón Hotchkiss de 37 mm utilizado en cruceros de fines del siglo XIX, conservado en el Museo Marítimo Nacional, Valparaíso". http://repositorioarchivohistorico.armada.cl/handle/1/7205. Retrieved 10 August 2021.

- ↑ Guns in the Anti-aircraft Museum (in Finnish)

Bibliography

- "Handbook of the 1-PR. Q.F. Gun (Mounted on Field Carriage)" War Office, UK, 1902.

- General Sir Martin Farndale, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: The Forgotten Fronts and the Home Base, 1914–18. London: Royal Artillery Institution, 1988. ISBN:1-870114-05-1

- I.V. Hogg & L.F. Thurston, British Artillery Weapons & Ammunition 1914–1918. London: Ian Allan, 1972. ISBN:978-0-7110-0381-1

- Brigadier N.W. Routledge, History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery: Anti-Aircraft Artillery, 1914–55. London: Brassey's, 1994. ISBN:1-85753-099-3

External links

- Handbook for the 1-pr. Q. F. gun, mounted on field carriage, 1902 at State Library of Victoria

- Anthony G Williams, 37MM AND 40MM GUNS IN BRITISH SERVICE

- Diagram of 1pr. Q.F. Mark I Land carriage at Victorian Forts and Artillery website

- Diagram of 1pr. Q.F. Mark II Land carriage at Victorian Forts and Artillery website

- DiGiulian, Tony Navweaps.com US Navy 1 pounder

|