Engineering:RMS Mauretania (1906)

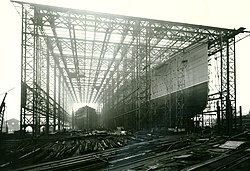

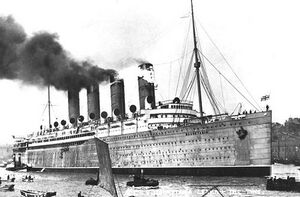

Mauretania in 1907 on the Tyne

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Mauretania |

| Namesake: | Mauretania |

| Owner: |

1906–1934: Cunard Line 1934–1935: Cunard White Star Line |

| Operator: |

|

| Port of registry: |

|

| Route: |

Liverpool–Queenstown–New York City (1907-1919) Southampton-Cherbourg-New York City (1919-1934) |

| Ordered: | 1904 |

| Builder: | Swan Hunter, Northumberland, England |

| Yard number: | 735 |

| Laid down: | 18 August 1904 |

| Launched: | 20 September 1906 |

| Christened: | 20 September 1906, by the Duchess of Roxburghe |

| Acquired: | 11 November 1907 |

| Maiden voyage: | 16 November 1907 |

| In service: | 1907–1934 |

| Out of service: | September 1934 |

| Fate: | Scrapped in 1935 at Rosyth, Scotland |

| General characteristics | |

| Type: | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage: | 31,938 GRT, 12,797 NRT |

| Displacement: | 44,610 tons |

| Length: | 790 ft (240.8 m) |

| Beam: | 88 ft (26.8 m) |

| Draft: | 33 ft (10.1 m) |

| Depth: | 33 ft 6 in (10.2 m) |

| Decks: | 8 |

| Installed power: |

|

| Propulsion: | Quadruple propeller installation |

| Speed: | 25 kn (46 km/h; 29 mph) ‐ 28 kn (52 km/h; 32 mph) design service speed |

| Capacity: |

|

| Crew: | 802 |

| Notes: | Largest ship in the world from 1907–1910. Running mate to RMS Lusitania and RMS Aquitania |

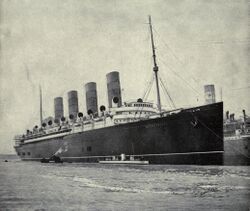

Mauretania was an ocean liner designed by Leonard Peskett and built by Wigham Richardson and Swan Hunter on the River Tyne, England for the British Cunard Line, launched on the afternoon of 20 September 1906. She was the world's largest ship until the launch of RMS Olympic in 1910. Mauretania captured the eastbound Blue Riband on the maiden return voyage in December 1907, then claimed the westbound Blue Riband for the fastest transatlantic crossing during her 1909 season. She held both speed records for 20 years.[1]

The ship's name was taken from the ancient Roman province of Mauretania on the northwest African coast, not the modern Mauritania to the south.[2] Similar nomenclature was also employed by Mauretania's sister Lusitania, which was named after the Roman province directly north of Mauretania, across the Strait of Gibraltar[2] in Portugal. Mauretania remained in service until September 1934, when Cunard-White Star retired her; scrapping commenced in Rosyth, in 1935.

Overview

In 1897 the German liner SS Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse became the largest and fastest ship in the world. With a speed of 22 knots (41 km/h; 25 mph), she captured the Blue Riband from Cunard Line's Campania and Lucania. Germany came to dominate the Atlantic, and by 1906 they had five four-funnel superliners in service, four of them owned by North German Lloyd.

At around the same time the American financier J. P. Morgan's International Mercantile Marine Co. was attempting to monopolise the shipping trade, and had already acquired Britain's other major transatlantic line, the White Star Line.[3]

In the face of these threats the Cunard Line was determined to regain the prestige of dominance in ocean travel not only for the company, but also for the United Kingdom.[3][4] By 1902, Cunard Line and the British government reached an agreement to build two superliners, Lusitania and Mauretania,[3] with a guaranteed service speed of no less than 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph). The British government was to loan £2,600,000 (£252 million in 2015)[5] for the construction of the ships, at an interest rate of 2.75%, to be paid back over twenty years, with a stipulation that the ships could be converted to armed merchant cruisers if needed.[6] Further funding was acquired when the Admiralty arranged for Cunard to be paid an additional sum per year to their mail subsidy.[6][7]

Design and construction

Mauretania and Lusitania were both designed by Cunard naval architect Leonard Peskett, with Swan Hunter and John Brown working from plans for an ocean greyhound with a stipulated service speed of twenty-four knots in moderate weather, as per the terms of her mail subsidy contract. Peskett's original configuration for the ships in 1902 was a three-funnel design, when reciprocating engines were destined to be the powerplant. A giant model of the ships appeared in Shipbuilder's magazine in this configuration. Cunard decided to change power plants to Parson's new turbine technology, and the ship's design was again modified when Peskett added a fourth funnel to the ship's profile. Construction of the vessel finally began with the laying of the keel in August 1904.[8] By tradition, the hull was painted in a light grey colour for photographic purposes during her launch; a common practice of the day for the first ship in a new class, as it made the lines of the ship clearer in the black-and-white photographs. Her hull was painted black after her maiden voyage.[9]

In 1906, Mauretania was launched by the Duchess of Roxburghe.[10] At the time of her launch, she was the largest moving structure ever built,[11] and slightly larger in gross tonnage than Lusitania. The main visual differences between Mauretania and Lusitania were that Mauretania was five feet longer and had different vents.[12] Mauretania also had two extra stages of turbine blades in her forward turbines, making her slightly faster than Lusitania. Mauretania and Lusitania were the only ships with direct-drive steam turbines to hold the Blue Riband; in later ships, reduction-geared turbines were mainly used.[13] Mauretania's usage of the steam turbine was the largest application yet of the then-new technology, developed by Charles Algernon Parsons.[14] During speed trials, these engines caused significant vibration at high speeds; in response, Mauretania received strengthening members aft and redesigned propellers before entering service, which reduced vibration.[15]

Mauretania was designed to suit Edwardian tastes. The ship's interior was designed by the architect Harold Peto, and her public rooms were fitted out by two notable London design houses – Ch. Mellier & Sons and Turner and Lord,[16][17] with twenty-eight different types of wood, along with marble, tapestries, and other furnishings such as the stunning octagon table in the smoking room.[16][18] Wood panelling for her first class public rooms was supposedly carved by three hundred craftsmen from Palestine but this seems unlikely, unnecessary and was probably executed by the yard or subcontracted, as were the majority of the second and third class areas.[19] The multi-level first-class dining saloon of straw oak was decorated in Francis I style and topped by a large dome skylight.[18] A series of elevators, then a rare new feature for liners, with grilles composed of the relatively new lightweight aluminium, were installed next to Mauretania's walnut grand staircase.[18] A new feature was the Verandah Café on the boat deck, where passengers were served beverages in a weather-protected environment, although this was enclosed within a year as it proved unrealistic.[16]

Comparison with the Olympic class

Lua error in Module:Multiple_image at line 163: attempt to perform arithmetic on local 'totalwidth' (a nil value). The White Star Line's Olympic-class vessels were almost 100 ft (30 m) longer and slightly wider than Lusitania and Mauretania. This made the White Star vessels about 15,000 gross register tons larger than the Cunard vessels. Both Lusitania and Mauretania were launched and had been in service for several years before Olympic, Titanic and Britannic were ready for the North Atlantic run. Although significantly faster than the Olympic class would be, the speed and port turnaround times of Cunard's vessels was not sufficient to allow the line to run a weekly two-ship transatlantic service from each side of the Atlantic. A third ship was needed for a weekly service, and in response to White Star's announced plan to build the three Olympic-class ships, Cunard ordered a third ship: Aquitania. Cunard's third ship Aquitania had a slightly lower service speed, but was a larger and more luxurious vessel.[citation needed]

With their increased size the Olympic-class liners could offer more amenities than Lusitania and Mauretania. Both Olympic and Titanic offered swimming pools, Turkish baths, a gymnasium, a squash court, large reception rooms, À la Carte restaurants separate from the dining saloons, and more staterooms with private bathroom facilities than their two Cunard rivals.[citation needed]

Heavy vibrations as a by-product of the four steam turbines on Lusitania and Mauretania plagued both ships throughout their careers. When Lusitania sailed at top speed the vibrations were so severe that Second and Third Class sections of the ship could become uninhabitable.[20] In contrast, the Olympic-class liners chose economy over speed by installing two traditional reciprocating engines and a turbine for the central propeller. With their greater tonnage and wider beam, the Olympic-class liners were also more stable at sea and less prone to rolling. Lusitania and Mauretania both featured straight prows in contrast to the angled prows of the Olympic liners. Designed so that the ships could plunge through a wave rather than crest it, the unforeseen consequence was that the Cunard liners would pitch forward alarmingly, even in calm weather, allowing huge waves to splash the bow and forward part of the superstructure.[21]

The vessels of the Olympic class also differed from Lusitania and Mauretania in the way in which they were compartmented below the waterline. The White Star vessels were divided by transverse watertight bulkheads. While Lusitania also had transverse bulkheads, she also had longitudinal bulkheads running along the ship on each side, between the boiler and engine rooms and the coal bunkers on the outside of the vessel. The British commission that had investigated the sinking of Titanic in 1912 heard testimony on the flooding of coal bunkers lying outside longitudinal bulkheads. Being of considerable length, when flooded, these could increase the ship's list and "make the lowering of the boats on the other side impracticable",[22] and this was what later happened with Lusitania. Furthermore, the ship's stability was insufficient for the bulkhead arrangement used: flooding of only three coal bunkers on one side could result in negative metacentric height.[23] On the other hand, Titanic was given ample stability and sank with only a few degrees list, the design being such that there was very little risk of unequal flooding and possible capsize.[24]

Lusitania did not carry enough lifeboats for all her passengers, officers and crew on board at the time of her maiden voyage (carrying four lifeboats fewer than Titanic would carry in 1912). This was a common practice for large passenger ships at the time, since the belief was that in busy shipping lanes help would always be nearby and the few boats available would be adequate to ferry all aboard to rescue ships before a sinking. After Titanic sank, Lusitania and Mauretania would be equipped with only six more clinker-built wooden boats under davits, making for a total of 22 boats rigged in davits. The rest of their lifeboat accommodations were supplemented with 26 collapsible lifeboats, 18 stored directly beneath the regular lifeboats and eight on the after deck. The collapsibles were built with hollow wooden bottoms and canvas sides, and needed assembly in the event they had to be used.[25]

Early career (1906–1914)

Mauretania departed Liverpool on her maiden voyage on 16 November 1907 under the command of Captain John Pritchard, but failed to capture the Blue Riband due to a rough storm that broke free her spare anchor. She also suffered minor damage to her superstructure. On the return voyage, however, (30 November – 5 December 1907) she captured the record for the fastest eastbound crossing of the Atlantic,[1] with an average speed of 23.69 knots (43.87 km/h; 27.26 mph).[1] On 23 December 1907, Mauretania was again at New York City and moored to Pier 54 in the North River when a squall with high winds struck, causing mooring posts on Pier 54 to give way. Mauretania went partially adrift, and her bow swung around and struck several barges which were bringing her coal and taking off ashes; the barges Roan and Tomhicken and the boats Eureka 32 and Eureka 36 were damaged and the barge Ellis P. Rogers was lost. In subsequent litigation, Cunard was found liable for damages.[26][27]

In September 1909, Mauretania captured the Blue Riband for the fastest westbound crossing—a record that was to stand for more than two decades.[1] In December 1911, as in New York City in December 1910, Mauretania broke loose from her moorings while in the River Mersey and sustained damage that caused the cancellation of her special speedy Christmas voyage to New York. In a quick change of events Cunard rescheduled Mauretania's voyage for Lusitania, which had just returned from New York, under the command of Captain James Charles. Lusitania completed Christmas crossings for Mauretania,[28] carrying travellers back to New York. Mauretania was on a westbound voyage from Liverpool to New York, beginning 10 April 1912, and was docked at Queenstown, Ireland, at the time of the RMS Titanic disaster. Mauretania was transporting Titanic's cargo manifest carried by registered mail. Traveling on Mauretania at the time was the chairman of Cunard, A. A. Booth, who organised a vigil for the Titanic victims.[29] In the spring of 1913 westbound transatlantic passage aboard Mauretania cost roughly $17 for third class passengers, as shown in the original ticket at right.[citation needed]

In July 1913, King George and Queen Mary were given a special tour of Mauretania, then Britain's fastest merchant vessel, adding further distinction to the ship's reputation. On 26 January 1914, while Mauretania was in the middle of annual refit in Liverpool, four men were killed[30][self-published source] and six injured when a gas cylinder exploded while they were working on one of her steam turbines. Damage to the ship was minimal; she was repaired in the new Gladstone drydock and returned to service two months later.[31]

First World War (1914–1919)

After Great Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, Mauretania made a dash for safety in Halifax, Nova Scotia, arriving on 6 August. Shortly after, she and Aquitania were requested by the British government to become armed merchant cruisers,[32] but their huge size and massive fuel consumption made them unsuitable for the duty,[33] and they resumed their civilian service on 11 August. Later, due to lack of passengers crossing the Atlantic, Mauretania was laid up in Liverpool until 7 May 1915, at the time that Lusitania was sunk by a German U-Boat.[citation needed]

Mauretania was about to fill the void left by Lusitania, but she was ordered by the British government to serve as a troop ship to carry British soldiers during the Gallipoli campaign.[33] She avoided becoming prey for German U-boats because of her high speed and the seamanship of her crew. As a troopship, she was painted in dark greys with black funnels, as were her contemporaries.[citation needed]

When combined forces from the British empire and France began to suffer heavy casualties, Mauretania was ordered to serve as a hospital ship, along with the Aquitania and White Star's Britannic, to treat the wounded until 25 January 1916. In medical service the vessel was painted white with buff funnels and large medical cross emblems[34] surrounding the vessel and possibly illuminated signs starboard and port. Seven months later, Mauretania once again became a troop ship late in 1916 when requisitioned by the Canadian government to carry Canadian troops from Halifax to Liverpool.[33] Her war duty was not yet over when the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, and she carried thousands of American troops.[citation needed]

The ship was known by the Admiralty as HMS Tuberose[35] until the end of the war,[33][dubious ] but the vessel's name was never changed by Cunard. Starting in March 1918, Mauretania received two forms of dazzle camouflage, a type of abstract colour scheme designed by Norman Wilkinson in 1917 in an effort to confuse enemy ships. The first camouflage scheme, applied early in March 1918, was curvilinear in nature and largely broad areas of olive with blacks, greys and blues. The second scheme was the more geometric design commonly referred to as "dazzle"; this design, applied by July 1918, was mostly several dark blues and greys with some black. After her war service, she was repainted in a drab grey scheme and finally full Cunard livery by the middle of 1919.[citation needed]

Post-war career (1919–1934)

Mauretania returned to civilian service on 21 September 1919, now serving on the Southampton to New York route.

Her busy sailing schedule prevented her from having an extensive overhaul scheduled in 1920. However, in 1921, Cunard removed her from service when fire broke out on E deck and decided to overhaul the ship.[36] She returned to the Tyne shipyard where she was built, where her boilers were converted to oil firing,[37] and returned to service in March 1922. Cunard noticed that Mauretania struggled to maintain her regular Atlantic service speed.

Although the ship's service speed had improved and it now burned only 750 short tons (680 t) of oil per 24 hours, compared to 1,000 short tons (910 t) of coal previously, it was not operating at her pre-war service speeds. On one crossing in 1922 the ship managed an average speed of only 19 knots (35 km/h; 22 mph).[citation needed]

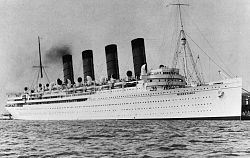

It was during these years her promenade was enclosed temporarily, and her funnels were modified to have an ovoid shape, making them look nearly identical to Lusitania. Cunard decided that the ship's once revolutionary turbines were in desperate need of an overhaul.[36] In 1923, a major refitting was begun in Southampton. Mauretania's turbines were dismantled. Halfway through the overhaul, the shipyard workers went on strike and the work was halted, so Cunard had the ship towed to Cherbourg, France, where the work was completed at another shipyard.[38] In May 1924, the ship returned to Atlantic service.[36]

The next several years would prove to Cunard that the changes made to Mauretania had helped, and she was a very popular and successful vessel during this time. In 1928, Mauretania was refurbished with a new interior design and in the next year her speed record was broken by the German liner Bremen,[39] with a speed of 28 knots (52 km/h; 32 mph). On 27 August, Cunard permitted the former ocean greyhound to have one final attempt to recapture the record from the newer German liner, but even her best efforts could only come just short of Bremen's record. She was taken out of service and her engines were adjusted to produce more power to give a higher service speed; however, this was still not enough. Bremen represented a new generation of ocean liners that were far more powerful and technologically advanced than the aging Cunard liner.[39] Even though Mauretania did not beat her German rival, the ship lost by just a fraction after decades of design improvement and beat all her own previous speed records both east and westbound. In 1929, Mauretania collided with a train ferry near Robbins Reef Light. No-one was killed or injured and her damage was quickly repaired.[citation needed]

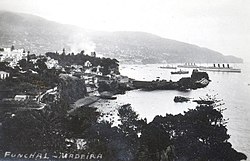

In 1930, with a combination of the Great Depression and newer competitors on the Atlantic run, Mauretania became a dedicated cruise ship[40] running six day cruises from New York to Pier 21 in Halifax, Nova Scotia.[41] On 19 November 1930, Mauretania rescued 28 people and the ship's cat of the Swedish cargo ship Ovidia which foundered in the Atlantic Ocean 400 nautical miles (740 km; 460 mi) south east of Cape Race, Newfoundland.[42][43] In 1932, she was painted white for cruise service. When Cunard Line merged with White Star Line in 1934, Mauretania, along with Olympic, Homeric, and other aging ocean liners, were deemed surplus to requirements and withdrawn from service.[citation needed]

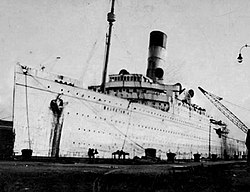

Retirement and scrapping

Cunard White Star withdrew Mauretania from service following a final eastward crossing from New York to Southampton in September 1934. The voyage was made at an average speed of 24 knots (44 km/h; 28 mph), equaling the original contractual stipulation for her mail subsidy. She was then laid up at Southampton, her twenty-eight years of service at a close.[37]

In May 1935 her furnishings and fittings were put up for auction by Hampton and Sons and on 1 July that year she departed Southampton for the last time to Metal Industries shipbreakers at Rosyth.[37] One of her former captains, the retired commodore Sir Arthur Rostron, captain of RMS Carpathia during the Titanic rescue, came to see her on her final departure from Southampton. Rostron refused to go aboard Mauretania before her final journey, stating that he preferred to remember the ship as she was when he commanded her.[citation needed]

En route to Rosyth, Mauretania stopped at her birthplace on the Tyne for half an hour, where she drew crowds of sightseers. Rockets were fired from her bridge,[44][self-published source] messages relayed, and she was boarded by the Lord Mayor of Newcastle. The mayor bade her farewell from the people of Newcastle, and her last captain, A. T. Brown, then resumed his course for Rosyth. Approximately 30 miles north of Newcastle is the small seaport of Amble, Northumberland. The local town council sent a telegram to the ship stating, "Still the finest ship on the seas." To which Mauretania replied with, "to the last and kindliest port in England, greetings and thanks."[45] Amble, to this day, is still known as 'Amble, the Friendliest Port', and this is still seen on signs when entering the town. With masts cut down to fit, the ship passed under the Forth Bridge and was delivered to the breakers.[citation needed]

Mauretania arrived at Rosyth in Scotland at about 6 am on 4 July 1935 during a half-gale, passing under Forth Bridge. By 6:30 am she passed the entrance to the Metal Industries yards under the command of Pilot Captain Whince. A lone kilted piper was present at the quayside, playing a funeral lament for the popular vessel. It was reported to author and historian John Maxtone-Graham that upon the final shut-down of her great engines, she gave a dark "final shudder...". Mauretania had her last public inspection on 8 July, a Sunday with 20,000 in attendance, with the monies raised going to local charities. Scrapping began shortly after and with great rapidity. Unusually, she was cut up afloat in drydock, with a complex system of wooden battens and pencil marks to monitor her balance. In a month her funnels were gone. By 1936 she was little more than a hulk, and she was beached at the tidal basin at Metal Industries and her remaining structure was scrapped by 1937.[46][self-published source]

To prevent a rival company using the name and to keep it available for a future Cunard White Star liner, arrangements were made for the Red Funnel Paddle Steamer Queen to be renamed Mauretania in the interim before the launch of the new RMS Mauretania in 1938.[47][page needed]

The demise of the beloved Mauretania was protested by many of her loyal passengers, including President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who wrote a private letter against the scrapping.[4]

Post-scrapping

The ship's bell is in the reception of the Lloyd's Register, Fenchurch Street, London. Annually for Remembrance Day, Lloyds Register observe two minutes of silence and lay a wreath at its base in honour of servicemen and women.

Some of the furnishings from Mauretania were installed in a bar/restaurant complex in Bristol called the Mauretania Bar (now Java Bristol), situated in Park Street. The bar was panelled with great quantities of richly carved and gilt old growth African mahogany, which came from her first class lounge.[48] The neon sign made for the 1937 opening on the south wall still advertises Mauretania and her bow lettering was used above the entrance.

Additionally, nearly the complete first class reading-writing room, with the original chandeliers and ornate gilt grilled bookcases, has been serving as the boardroom at Pinewood Studios, west of London. The colour is no longer shimmering silver sycamore – it has been altered over the years to an amber.[4] According to a Channel 4 programme about coast properties the whole of the Second Class drawing room from the ship form the interior of a white and blue house overlooking Poole Harbour; the drawing room is overlooked by a balustraded circular veranda which is also original. Other panels and fittings were used to decorate the foyer and auditorium areas of the now defunct Windsor Cinema in Carluke.[49] Some of the timber panelling was also used in the extension (completed in 1937) of St John the Baptist's Catholic Church in Padiham, Lancashire.[50]

In 2010, an African mahogany pilaster from the first class lounge, fluted with an intricate gilt acanthus motif and intact rams head capital, was discovered and restored; since 2012, it has been on permanent display in the Discovery Museum's Segedunum Annex at Wallsend, just a few hundred yards from where it was carved and installed in the Swan Hunter fitting out basin, over a century earlier. Many examples of the liner's fixtures and fittings exist in private collections as well, including large sections of moulding, panelling, ceilings and samples of her turbine blades.[51][self-published source] The original wheelhouse ( port high pressure turbine) telegraph from the Mauritania is on display in the lobby of the QE2, which now serves as a five star hotel, in Dubai.

An original model of Mauretania is displayed at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. after a long stay on the retired Queen Mary in Long Beach, California. Originally with a black hull, it was repainted to show her white cruising paint scheme in the 1930s after it was gifted to the RMS Queen Mary by Franklin Delano Roosevelt.[52]

Another scale model of Mauretania is displayed at the Discovery Museum in Newcastle upon Tyne. It is still in its original color scheme.

A large builder's model, showing Mauretania in her white cruising paint scheme, is displayed in the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic's Cunard exhibit in Halifax, Nova Scotia. Originally a model of Lusitania, it was converted to represent Mauretania after Lusitania was torpedoed.[53]

Another large builder's model is situated aboard the ocean liner Queen Elizabeth 2, currently located in Dubai. This model was also originally Lusitania, and, like the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic's model, it was converted into Mauretania after Lusitania was lost.[54][self-published source] When inspecting the model, one can tell it was Lusitania by examining the different boom crutches and bridge front, which is on the boat deck level.[citation needed]

A model of the vessel which was commissioned by Cunard is now held in the collection of the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich.[55]

In popular culture

Mauretania is remembered in a song, "The fireman's lament" or "Firing the Mauretania", collected by Redd Sullivan.[56] The song starts "In 19 hundred and 24, I ... got a job on the Mauretania"; but then goes on to say "shovelling coal from morn till night" (not possible in 1924 as she was oil-fired by then). The number of "fires" is said to be 64. Hughie Jones also recorded the song but the last verse of Hughie's version calls upon "all you trimmers" whereas Redd Sullivan's version calls upon "stokers".[lower-roman 1]

The Clive Cussler Isaac Bell novel The Thief is set aboard Mauretania. A terrible fire engulfs the forward storage area but it is brought under control.

Mauretania is also mentioned in Rudyard Kipling's poem "The Secret of the Machines":

The boat-express is waiting your command!

You will find the Mauretania at the quay,

Till her captain turns the lever 'neath his hand,

And the monstrous nine-decked city goes to sea.

Mauretania is mentioned at the beginning of James Cameron's Titanic, when Rose DeWitt Bukater (Kate Winslet) says that Titanic does not appear larger than Mauretania, her snobbish fiancé Caledon Hockley (Billy Zane) explains to her that Titanic is much larger and more luxurious than Mauretania.

The historical novel Maiden Voyage by British writer Roger Harvey set in Newcastle in the 1900s gives an accurate account of the building of Mauretania and features characters involved with her turbine engines. The climax of two love stories and a thriller comes as the ship approaches New York on her maiden voyage.

The ship that Spencer Dutton used to return the message from his aunt to return to the Yellowstone Ranch in "1923".[57]

See also

Notes

- ↑ A stoker shovelled coal into the furnaces of the boilers. A trimmer worked in the coal bunkers, bringing more coal forward as the nearer coal was used by the stokers. A boilerman was a more skilled role, with some responsibility for managing the operation of the boiler.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Maxtone-Graham 1972, pp. 41–43.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 24.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 11.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Floating Palaces. (1996) A&E. TV documentary. Narrated by Fritz Weaver.

- ↑ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. https://measuringworth.com/ukearncpi/. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Layton, J. Kent. (2007) Lusitania: An Illustrated Biography, Lulu Press, pp. 3, 39.

- ↑ Vale, Vivian, The American Peril: Challenge to Britain on the North Atlantic, 1901–04, pp. 143–183.

- ↑ "Mauretania". http://collectionsprojects.org.uk/mauretania/story-construction.html.

- ↑ Piouffre 2009, p. 52.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 25.

- ↑ "RMS Mauretania Construction". Tyne and Wear Archives Service. http://www.tyneandweararchives.org.uk/mauretania/story-construction.html.

- ↑ Layton 2007, p. 44.

- ↑ Williams, Trevor. (1982) A short history of twentieth-century technology. Oxford University Press, p. 174.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 15.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 "RMS Mauretania Fitting Out". Tyne and Wear Archives Service. http://www.tyneandweararchives.org.uk/mauretania/story-fitting%20out.html.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 31.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Maxtone-Graham 1972, pp. 33–36.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 33.

- ↑ Archibald, Rick & Ballard, Robert.The Lost Ships of Robert Ballard, Thunder Bay Press: 2005; p. 46.

- ↑ Archibald, Rick & Ballard, Robert."The Lost Ships of Robert Ballard," Thunder Bay Press: 2005; pp. 51–52.

- ↑ "British Wreck Commissioner's Inquiry, Day 19, Testimony of Edward Wilding, recalled (20227)". https://www.titanicinquiry.org/BOTInq/BOTInq19Wilding01.php.

- ↑ Layton 2010, p. 55.

- ↑ Hackett & Bedford 1996, p. 171.

- ↑ Simpson 1972, p. 159.

- ↑ Anonymous, The Federal Reporter, Volume 174, St. Paul, Minnesota: West Publishing Company, 1910, pp. 166–175.

- ↑ Department of Commerce and Labor Bureau of Navigation Fortieth Annual List of Merchant Vessels of the United States for the Year Ending June 30, 1908, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1908, p. 383.

- ↑ Layton 2007, p. 120.

- ↑ "TIP – Titanic Related Ships – Mauretania – Cunard Line". http://www.titanicinquiry.org/ships/mauretania.php.

- ↑ [1][self-published source]

- ↑ Tansley, Janet (13 January 2016). "Nostalgia: Cunard's super ship RMS Mauretania". http://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/nostalgia/nostalgia-january-relaunch-cunards-super-10729164.

- ↑ Layton 2007, pp. 170–171.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 "RMS Mauretania War Service". Tyne and Wear Archives Service. http://www.tyneandweararchives.org.uk/mauretania/story-warservice.html.

- ↑ "Luxury liner played vital war role". BBC News. 13 November 2014. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-tyne-29629205.

- ↑ Ocean liners of the past: the Cunard express liners Lusitania and Mauretania. Published by Patrick Stephens, 1970 (p. 207).

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 "RMS Mauretania Final (Service)". Tyne and Wear Archives Service. http://www.tyneandweararchives.org.uk/mauretania/story-final.html.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Maxtone-Graham 1972, pp. 342–345.

- ↑ "Mauretania". http://collectionsprojects.org.uk/mauretania/story-final.html.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 255.

- ↑ Maxtone-Graham 1972, p. 340.

- ↑ "Website Update | Nova Scotia Archives". 20 April 2020. https://novascotia.ca/archives/virtual/tourism/results.asp?SearchList1=3&Language=English.

- ↑ "Swedish steamer abandoned". The Times (London) (45675): col E, p. 16. 20 November 1930.

- ↑ "Rescued Swedish crew". The Times (London) (45676): col F, p. 13. 21 November 1930.

- ↑ "Welcome to North Atlantic Run". http://www.northatlanticrun.com/735/Tyne_Departure.html.[self-published source]

- ↑ "Why we are known as "The Friendliest Port" – The Ambler". 11 December 2012. http://www.theambler.co.uk/2012/12/11/why-we-are-known-as-the-friendliest-port/.

- ↑ Longo, Eric K. (8 July 2010). "Mauretania 75th Anniversary". http://edwardianliners.weebly.com/mauretania-75th-anniversary.html.[self-published source]

- ↑ Adams, R. B. [1986] Red Funnel and Before. Kingfisher Publications.[page needed]

- ↑ "Mauretania back on the market – News – Bristol 24/7". 10 November 2016. https://www.bristol247.com/news-and-features/news/mauretania-bristol-made-available-to-let/.

- ↑ Graham, Hugh (30 April 2017). "Step aboard Dorset's most unusual holiday home" (in en). https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/step-aboard-dorsets-most-unusual-holiday-home-wnmkvzchz.

- ↑ "Padiham – St John the Baptist". Catholic Trust for England and Wales and English Heritage. 2011. http://taking-stock.org.uk/building/padiham-st-john-the-baptist/.

- ↑ Longo, Eric K.. "The Mauretania Pilaster". http://edwardianliners.weebly.com/the-mauretania-pilaster.html.[self-published source]

- ↑ "Ship model, RMS Mauretania" (in en). http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_1342703.

- ↑ Paul Moloney, "Toronto's Lusitania model bound for Halifax", Toronto Star, 30 January 2010.

- ↑ "The Mauretania model on board QE2" The QE2 Story[self-published source]

- ↑ "Ship models – magnificent Mauretania". 28 May 2015. http://www.rmg.co.uk/discover/behind-the-scenes/blog/ship-models-magnificent-mauretania.

- ↑ Hugill, Stan in Spin, The Folksong Magazine, Volume 1, # 9, 1962.

- ↑ Maiden Voyage by Roger Harvey, New Generation (2017), ISBN:978-1-78719-357-4

Works cited

- Hackett, C.; Bedford, J.G. (1996). The sinking of S.S. Titanic: Investigated by Modern Techniques. Royal Institution of Naval Architects. p. 171.

- Layton, J. Kent (2007). Lusitania: An Illustrated Biography (2nd ed.). Stroud, Gloucs: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4456-4262-8.

- Layton, J. Kent (2010). The Edwardian Superliners: A Trio of Trios. Stroud, Gloucs: Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84868-835-3. http://www.atlanticliners.com/atlantic_liners_book.htm.

- Maxtone-Graham, John (1972). The Only Way to Cross. New York: Macmillan. ISBN 0-02-582350-7. https://archive.org/details/onlywaytocrosste0000maxt.

- Piouffre, Gérard (2009) (in fr). Le Titanic ne répond plus. Paris: Larousse. ISBN 978-2-03-584196-4.

- Simpson, Colin (1972). Lusitania. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-00-3793-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=MfoXnQEACAAJ. Retrieved 17 March 2015.

Further reading

- Doubleday, F.N. (January 1908). "A Trip on the Two Largest Ships". The World's Work: A History of Our Time XV: 9803–9810. https://books.google.com/books?id=hKPvxXgBN1oC&pg=PA9803. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- Jordan, Humfrey (1936). Mauretania: Landfalls and Departures of Twenty-Five Years. Hodder and Stoughton: London. OCLC 919719086.

- Newall, Peter (2006). Mauretania: Triumph and Resurrection. Longton, Preston, Lancs: Ships in Focus Publications. ISBN 1-901703-53-3.

- Tyne and Wear County Council Museum Service (c. 1984). The Mauretania. Tyne and Wear County Council Museum Service. http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Mauretania_handout_front.jpg.

External links

- Tyne & Wear Archives Service Mauretania website

- Mauretania Home at Atlantic Liners

- "Mauretania". Chris' Cunard Page. https://www.chriscunard.com/history-fleet/cunard-fleet/1900-1930/mauretania/.

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Lusitania |

Holder of the Blue Riband (westbound record) 1909–1929 |

Succeeded by Bremen |

| Blue Riband (eastbound record) 1907–1929 | ||

|