Engineering:SS Princess Alice (1865)

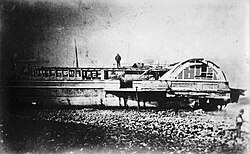

Contemporary engraving of Bywell Castle bearing down on Princess Alice

Script error: The function "infobox_ship_career" does not exist. | |

| General characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Type: | passenger steamer[1] |

| Tonnage: | 171 GRT[1] |

| Length: | 219.4 ft (66.9 m)[1] |

| Beam: | 20.2 ft (6.2 m)[1] |

| Draught: | 8.4 ft (2.6 m)[1] |

| Installed power: | 140 NHP 2 cylinder oscillating steam engine[1] |

| Propulsion: | paddle[1] |

SS Princess Alice, formerly PS Bute, was a passenger paddle steamer.[1] She was sunk in 1878 in a collision off Tripcock Point on the River Thames with the collier Bywell Castle that resulted in the loss of over 650 lives, the greatest loss of life of any British inland waterway shipping disaster.[2][3]

Early service

Caird & Company of Greenock launched Bute in 1865 for the Wemyss Bay Railway Company, for whom she plied between Wemyss Bay and Rothesay.[1] She was sold in 1867 to the Waterman's Steam Packet Co.[1] on the River Thames, who renamed her Princess Alice. She was sold again in 1870 to the Woolwich Steam Packet Co. and in 1875 to the London Steamboat Company, who operated her as an excursion steamer.[1]

The disaster

On 3 September 1878 Princess Alice was making what was billed as a "Moonlight Trip" to Gravesend and back.[3] This was a routine trip from Swan Pier near London Bridge to Gravesend and Sheerness. Tickets were sold for two shillings.[3] Hundreds of Londoners paid the fare; many were visiting Rosherville Gardens in Gravesend.[3]

By 7:40 PM, Princess Alice was on her return journey and within sight of the North Woolwich Pier[3]—where many passengers were to disembark—when she sighted the Newcastle bound vessel SS Bywell Castle.[3] Bywell Castle displaced 890 long tons (904 t), more than three times that of Princess Alice.[3] She usually carried coal to Africa: at the time, she had just been repainted at a dry dock and was on her way to pick up a load of coal. Her master was Captain Harrison, who was accompanied by an experienced Thames river pilot. The collier was coming down the river with the tide at half speed.

On the bridge of Bywell Castle, Harrison observed the port light of Princess Alice; he set a course to pass to starboard of her. However, the Master of Princess Alice, 47-year-old Captain William R.H. Grinsted, labouring up the river against the tide, followed the normal watermen's practice of seeking the slack water on the south side and altered Princess Alice's course to port, bringing her into the path of Bywell Castle.[4] Captain Harrison ordered Bywell Castle's engines reversed, but it was too late; Princess Alice was struck on the starboard side; she split in two and sank within four minutes.

Many passengers were trapped within the wreck and drowned: piles of bodies were found around the exits of the saloon when the wreck was raised. The twice-daily release of 75 million imperial gallons (340,000 m3) of raw sewage from sewer outfalls at Barking and Crossness[3] had occurred one hour before the collision; the heavily polluted water was believed to have contributed to the deaths of many of those who went into the river. It was noted that the sunken corpses began rising to the surface after only six days, rather than the usual nine. More than 650 people died, and between 69 and 170 were rescued. Several of those rescued died within the following weeks, in part from the effects of the contaminated water swallowed.[3] 120 victims were buried in a mass grave at Woolwich Old Cemetery, Kings Highway, Plumstead.[3] A memorial cross was erected to mark the spot, "paid for by national sixpenny subscription to which more than 23,000 persons contributed".

The log of Bywell Castle described the incident:

The master and pilot were on the upper bridge, and the lookout on the top-gallant forecastle; light airs prevailed; the weather was a little hazy; at 7:45 o'clock P. M. proceeded at half speed down Gallion's Reach; when about at the centre of the reach observed an excursion steamer coming up Barking Reach, showing her red and masthead lights, when we ported our helm to keep out toward Tripcock Point; as the vessels neared, observed that the other steamer had ported her helm. Immediately afterward saw that she had starboarded her helm and was trying to cross our bows, showing her green light close under our port bow. Seeing that a collision was inevitable, we stopped our engines and reversed them at full speed. The two vessels came in collision, the bow of Bywell Castle cutting into the other steamer with a dreadful crash. We took immediate measures for saving life by hauling up over our bows several passengers, throwing overboard ropes' ends, life-buoys, a hold-ladder, and several planks, and getting out three boats, at the same time keeping the whistle blowing loudly for assistance, which was rendered by several boats from shore, and a boat from another steamer. The excursion steamer, which turned out to be Princess Alice, turned over and sank under our bows. We succeeded in rescuing a great many passengers, and anchored for the night.[5]

The subsequent Board of Trade enquiry blamed Captain Grinsted, who had died in the disaster, finding that "the Princess Alice was not properly and efficiently manned; also, that the numbers of persons aboard were more than was prudent and that the means of saving life on board the paddle steamer was inadequate for a vessel of her class". The jury of the Coroner's Inquest, held at the same time on the opposite bank of the river, said "that the Bywell Castle did not take the necessary precaution of easing, stopping and reversing her engines in time and that the Princess Alice contributed to the collision by not stopping and going astern, that all collisions in the opinion of the jury might in future be avoided if proper and stringent rules and regulation were laid down for all steam navigation on the River Thames". But the jury agreed that the number of persons aboard Princess Alice was more than was prudent and that the means of lifesaving were inadequate.[6]

Local people had a different point of view to the enquiry: "Many Thames watermen considered that, as all experienced Thames pilots were well aware that 'working the slack' on the south side of the river was a common and accepted practice of the day, the pilot of Bywell Castle should have realised the situation and acted accordingly, but no watermen were called to give evidence at the inquest or subsequent enquiry".[7] The Thames Conservancy had published by-laws in 1872 which mandated the 'port to port' rule and there was no provision for exceptions.

The press also railed against the captain of the collier, with endless speculation and The Illustrated London News publishing a full-spread picture showing Princess Alice facing in the opposite direction, being 'run down'. Despite the verdict exonerating him, Captain Harrison's health broke down, and he never returned to sea.[8]

Six ensigns of the 30th Regiment of Foot, including Charles O'Brien, later a prominent colonial administrator, missed Princess Alice (and likely death) by a matter of seconds.[9] Elizabeth Stride, later one of the victims of Jack the Ripper, claimed to have survived the disaster and that her husband and children were killed in it: in fact her husband died of tuberculosis, and they were childless.

At this time there was no official body responsible for marine safety in the Thames. The subsequent inquiry resolved that the Marine Police Force, based at Wapping, be equipped with steam launches, to replace their rowing boats and make them better able to perform rescues.[10] A new plan for dumping sewage far out at sea via boat, rather than simply releasing it downriver, was also formulated, but not implemented.

The new Royal Albert Dock, which helped to separate heavy goods traffic from the smaller boats, and adoption of emergency signalling lights on boats across the globe, are considered to be responses to the disaster.[11] The Princess Alice accident also produced a change to the Burial of Drowned Persons Act which extended the obligation on parishes to bury dead persons cast ashore from the sea to include all tidal or navigable waters. Previously, payments were not made for the recovery of corpses, and bodies were allowed to float up and down rivers.[12][13]

See also

- List of United Kingdom disasters by death toll

- List of maritime disasters in the 19th century

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedClyde - ↑ White, Jerry (2007). London in the 19th Century. Vintage. p. 264.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 "Princess Alice disaster: The Thames' 650 forgotten dead". 3 September 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-44800309. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ Dix, Frank L. (1985). Royal River Highway. David & Charles, Newton Abbot. p. 96.

- ↑ "Log of the Steamer Bywell Castle". New York Times (6 September 1878). https://query.nytimes.com/gst/abstract.html?res=F00910FF3E5A127B93C4A91782D85F4C8784F9. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ↑ Thames Police. "Thames Police: History - Princess Alice Disaster 'Inquest findings'.". http://www.thamespolicemuseum.org.uk/h_alice_12.html. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ Dix 1985, p. 97

- ↑ Thames Police

- ↑ "Obituary of Sir Charles O'Brien". The Times (2 December 1935).

- ↑ "official history". Metropolitan Police. Archived from the original on 16 July 2007. https://web.archive.org/web/20070716200107/http://www.met.police.uk/msu/history.htm. Retrieved 26 Jan 2007.

- ↑ Evans, Alice (3 September 2018). "Princess Alice disaster: The Thames' 650 forgotten dead". BBC. BBC (BBC). https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-london-44800309. Retrieved 3 September 2018.

- ↑ "DROWNED PERSONS (DISCOVERY AND INTERMENT) BILL. SECOND READING". 24 March 1886. https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1886/mar/24/second-reading-2.

- ↑ "The Collision On The Thames". Times [London, England]: p. 7. 1 October 1878. http://find.galegroup.com/ttda/infomark.do?&source=gale&prodId=TTDA&userGroupName=rtl_ttda&tabID=T003&docPage=article&searchType=&docId=CS118537025&type=multipage&contentSet=LTO&version=1.0.

External links

- Thames Police Museum record

- The Princess Alice Disaster from The Records of the Woolwich District by W. T. Vincent

- Lacey, R. (2007), Great Tales from English History. ISBN 978-0-349-11731-7.

- Whymper, Frederick. (1880), The Sea : its stirring story of adventure, peril & heroism, (4 vols), iv, 282.

[ ⚑ ] 51°30′38″N 0°05′25″E / 51.51054°N 0.09015°E