Engineering:Supermarine Channel

| Channel | |

|---|---|

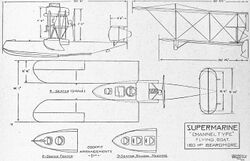

Advertisement for Supermarine featuring the Channel Type (1921) | |

| General information | |

| Type | Flying boat, designed to be operated as a commercial aircraft, or by the military |

| Manufacturer | Supermarine |

| Designer | R.J. Mitchell |

| Number built | 10 |

| History | |

| Introduction date | 1919 |

| Developed from | AD Flying Boat |

| Developed into | Supermarine Commercial Amphibian |

The Supermarine Channel (originally the Supermarine Channel Type) was a modified version of the AD Flying Boat, purchased by Supermarine from the British Air Ministry and modified for the civil market with the intention of beginning regular air flights across the English Channel. The aircraft were given airworthiness certificates in July 1919. The Mark I version, later called the Channel I, was powered with a 160 horsepower (120 kW) Beardmore engine; a variant designated as Channel II was fitted with a 240 horsepower (180 kW) Armstrong Siddeley Puma engine. Designed by Supermarine to accommodate up to four passengers, the company produced a series of interchangeable interiors that could be used at short notice, which enabled the Channel to be used as a fighter or for training purposes.

The Channel was first used from August 1919, when it flew passengers across the Solent and to the Isle of Wight. Norway's first airline Det Norske Luftfartsreder A/S of Christiania purchased three of the aircraft in 1920, and four aircraft were ordered for the Norwegian Armed Forces, which began operating from May that year. A Channel was used by the New Zealand Flying School, and Channel II aircraft were sent to Bermuda as part of a project to promote aviation in the region and transported to Venezuela to be used to undertake the survey for oil at the delta of the Orinoco. In 1921 the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service acquired three Channel II flying boats which were shipped out with the British-led Sempill Mission to Japan.

Design and development

The ban on commercial flights in the United Kingdom imposed during World War I was lifted in May 1919. With the intention of beginning regular air flights over short-haul sea routes across the English Channel, Supermarine purchased ten AD Flying Boats that during the war had been kept in storage by the military after their construction. The AD Flying Boat was designed in 1915 by the British yacht designer Linton Hope.[1]

After acquiring the AD Flying Boats, Supermarine modified them for the civil market, before being given airworthiness certificates in July 1919.[2][3] The aircraft was redesigned to accommodate up to four passengers, although limited to three if amphibian landing gear was fitted.[4] the modified aircraft were rebranded as the Supermarine Channel Type, with the name 'Channel' first appearing on 2 April 1920.[5][6] Attention was paid towards the comfort of the passengers, who were provided with compartments that could be either closed over or left open (with a windscreen included to protect them from the wind and spray), and seats that were kept clean by being designed to spring up when not in use.[7]

In October 1920, the aeronautical magazine Flight described the aircraft as able “to delight the heart of any sea-faring man, for they are pre-eminently the product of men who know and understand the sea and its ways”.[7] The Channel's engine was a 160 horsepower (120 kW) Beardmore 160 hp,[8] separated from the wing structure and fixed at the top of an A-shaped frame to prevent vibrations from passing to the wings. Because of the position of the engine, the tail unit was made with two planes.[7] The Channel was equipped with an anchor and a boathook. Mitchell's team produced a series of interchangeable interiors that could be used at short notice, enabling it to be used as a fighter or for training purposes.[8][9]

The Supermarine Commercial Amphibian, a passenger-carrying flying boat that was the first aircraft to be designed by Mitchell, was based on the Supermarine Channel. It was built at the company's works at Woolston, Southampton for an Air Ministry competition that took place during September 1920.[10]

Operational history

England

The new civilian air services from the Port of Southampton to Bournemouth and to the Isle of Wight began in early August 1919.[11] Of the ten Channels, five were put to regular use, whilst the others were held in reserve, so allowing plenty of time for maintenance work to be done on them all.[3]

The new service was used in a variety of different ways: ferry passengers who had missed their boat to the Isle of Wight could embark from Bournemouth Pier for the flight across the Solent; and spectators attending the Cowes Regatta had the opportunity to view the yachting from the air in a Channel.[12] During the British railway strike of 1919, Channels were used to deliver newspapers around the south coast. On 28 September 1919, Supermarine operated the first international flying boat service,[13] when Channel I aircraft for a short period carried paying passengers from Woolston to Le Havre,[14] replacing the steam packets that had stopped operating in support of the railway strike.[15] Supermarine suspended flights to the Isle of Wight during the winter months, and whenever poor weather conditions occurred.[6]

Norway

In May 1920 Norway's first airline Det Norske Luftfartsreder A/S of Christiania purchased three Supermarine Channels.[6][16] The Bergen-Haugesund-Stavanger service was inaugurated in August 1920, carrying mail and passengers. The airline later acquired three Friedrichshafen floatplanes, which with their more powerful engines, made it difficult for the Channels to keep up with them. Over 200 flights were completed up to December 1920, after which the service was withdrawn due to a lack of passengers and the high cost of mail delivery by air.[16]

The Norwegian government issued a specification for eight naval seaplanes in June 1919, and after accepting Supermarine's tender for Channels, four aircraft were ordered for the Norwegian Armed Forces, which began operating from May 1920.[17][18] During their operational history, two of the aircraft (planes F-40 and F-44) were re-engined with more powerful Puma engines. After noting the improvement to the performance of the Norwegians' aircraft, Supermarine re-engined their own Channel flying boats, later allotting them with the name Channel II.[19]

New Zealand, Bermuda, Venezuela and Japan

In 1921 a Channel I was delivered to the New Zealand company Walsh Brothers for use by the New Zealand Flying School. On 4 October 1921 the aircraft, by then registered as G-NZAI, made the first flight from Auckland to Wellington. Fiji was surveyed when the Channel made the first flight to the islands in July 1921. G-NZAI was broken up when the New Zealand government took over the Flying School's assets after it was forced to close in 1924.[20]

In 1920, Channels saw service in Bermuda, when three of the aircraft were used as part of a project to promote aviation in the region.[19] Hal Kitchener of the Royal Flying Corps returned to Bermuda and in the spring of that year formed with a partner the short-lived Bermuda and West Atlantic Aviation Company, with the aim of making Bermuda a base for aerial surveys. Several aircraft were delivered to the company, including three Avro 504 sea planes and three Channel I flying boats; and hangars and a slipway were built at Hinson's Island.[21][22][23]

In 1921 the British Controlled Oilfields Company contracted the Bermuda and West Atlantic Aviation Company Limited with the aim of producing an aerial survey of the delta region of the Orinoco. After being modified to be equipped with specialist camera equipment and tested in Britain, two Channel II aircraft were transported by ship across the Atlantic Ocean to be used to undertake the survey.[24][25] The expedition team, led by Cochran Patrick, included two pilots, three mechanics and four photographers, surveyed the numerous unmapped small streams and mangrove swamps, a task that was considered to be near impossible without the use of aircraft.[26]

On 14 March 1921, the Channel was demonstrated to a Japanese naval delegation that included the chief of the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service, who was aboard when it flew around the Isle of Wight and the Solent during a strong gale.[27] The delegation was impressed enough by the aircraft's performance for three Channel II flying boats to be acquired by the Japanese and shipped out with the British-led Sempill Mission to Japan.[18][28]

Military operators

Chile

Chile

- Chilean Air Force – acquired one aircraft.[8]

- Chilean Navy acquired one Channel with modified hull (similar to the Supermarine Seal II) in 1922.[8]

Japan

Japan

- Imperial Japanese Navy purchased three Channels.[8]

Norway

Norway

- Royal Norwegian Navy Air Service purchased four Beardmore engined Channels in 1920, acquiring a further ex-civil aircraft. One remained in service until 1928.[29]

Sweden

Sweden

- Royal Swedish Navy purchased a single Channel in 1921, which was destroyed during testing.[8]

Specifications (Channel I)

Data from Supermarine Aircraft since 1914[8]

General characteristics

- Crew: five, pilot and four passengers

- Length: 30 ft (9.1 m)

- Upper wingspan: 50 ft 5 in (15.37 m)

- Lower wingspan: 39 ft 7 in (12.07 m)

- Height: 13 ft (4.0 m)

- Wing area: 453 sq ft (42.1 m2)

- Empty weight: 2,356 lb (1,069 kg)

- Gross weight: 3,400 lb (1,542 kg)

- Powerplant: 1 × Beardmore Piston aero engine, 160 hp (120 kW)

Performance

- Maximum speed: 80 mph (130 km/h, 70 kn) at 2,000 ft (610 m)

- Cruise speed: 53 mph (85 km/h, 46 kn)

- Endurance: 3 hr

- Service ceiling: 3,000 ft (910 m)

- Rate of climb: 200 ft/min (1.0 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 30 min to 10,000 ft (3,050 m)

References

- ↑ Bruce 1957, p. 3.

- ↑ Pegram 2016, p. 21.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 29.

- ↑ "The "Channel Type"". The Aeroplane (London: Temple Press) 19 (2 (1st Report of the Aero Show)): 140–142. 14 July 1920. https://archive.org/details/aeroplane191920lond/page/138/mode/2up?q. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 4, 29.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Pegram 2016, p. 27.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "The "Channel Type"". The Aeroplane (London: Temple Press) 19 (2 (1st Report of the Aero Show)): 138. 14 July 1920. https://archive.org/details/aeroplane191920lond/page/138/mode/2up?q. Retrieved 11 September 2011.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 40.

- ↑ Pegram 2016, pp. 21, 27.

- ↑ Pegram 2016, pp. 29–30.

- ↑ "Civil Aerial Transport Notes". The Aeroplane (London: Temple Press). 6 August 1919. https://archive.org/details/aeroplan171919lond/page/548/mode/2up?q=. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 30.

- ↑ Roussel 2013, p. 52.

- ↑ Roussel 2013, p. 51.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 30–31.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 35.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Pegram 2016, p. 28.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 36.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ Longley-Cook, L.H. (25 June 2021). "The Many Lives of Hinson's Island". The Bermudian. https://www.thebermudian.com/culture/our-bermuda/the-many-lives-of-hinsons-island/.

- ↑ Forbes, Keith Archibald (2020). "Bermuda's History 1900 to 1939 pre-war". http://www.bermuda-online.org/history1900-1939prewar.htm.

- ↑ "New Company Registered". Flight International (London: Royal Aero Club) 16 (12): 434. 15 April 1920. https://archive.org/details/Flight_International_Magazine_1920-04-15-pdf/page/n25/mode/2up?q=. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ↑ "Oil-Prospecting by Supermarine". Flight International (London: Royal Aero Club) 13 (13): 225. 31 March 1921. https://archive.org/details/Flight_International_Magazine_1921-03-31-pdf/page/n7/mode/2up?q=. Retrieved 12 September 2021.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 37–38.

- ↑ Burchall 1922, p. 119.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, p. 39.

- ↑ Hillman & Higgs 2020, p. 146.

- ↑ Andrews & Morgan 1981, pp. 35–36.

Sources

- Andrews, Charles Ferdinand; Morgan, Eric B. (1981). Supermarine Aircraft since 1914. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-03701-0-018-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=p3NTAAAAMAAJ.

- Bruce, J. M. (1957). British Aeroplanes 1914–18. London: Putnam. ISBN 978-03700-0-038-1.

- Burchall, P. R. (March 1922). "An Investigation of the Possibilities Attaching to Aerial Co-Operation with Survey, Map - Making and Exploring Expeditions". Royal United Services Institution. Journal (Royal United Services Institution) 67 (465): 112–127. doi:10.1080/03071842209420188. https://journals.scholarsportal.info/details/00359289/v67i0465/112_aiotpasmmaee.xml.

- Hillman, Jo; Higgs, Colin (2020). Supermarine Southampton: The Flying Boat that Made R.J. Mitchell. Air World. ISBN 978-15267-8-497-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=HjsTEAAAQBAJ.

- Pegram, Ralph (2016). Beyond the Spitfire: The Unseen Designs of R.J. Mitchell. Pegram: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7509-6515-6.

- Roussel, Mike (2013). Spitfire's Forgotten Designer: The Career of Supermarine's Joe Smith. Brimscombe Port: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-8759-5.

Further reading

- "The 1920 Olympia Aero Show". Flight International (London: Royal Aero Club) 12 (30): 800–802. 22 July 1920. https://archive.org/details/sim_flight-international_1920-07-22_12_30/page/800/mode/2up?q=supermarine+channel.

External links

- Images of the Supermarine Channel I delivered to the New Zealand Flying School in 1921

- Information from the website 'Military Aviation in Sweden' about the Channel II that was acquired by the Swedish Navy in 1921

|