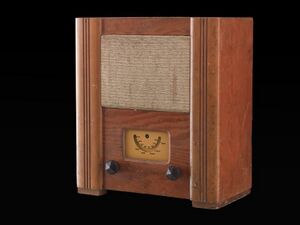

Engineering:Utility Radio

The Utility Radio or Wartime Civilian Receiver was a valve domestic radio receiver, manufactured in Great Britain during World War II starting in July 1944. It was designed by G.D. Reynolds of Murphy Radio. Both AC and battery-operated versions were made.[1][2][3]

History

When war broke out in 1939, British radio manufacturers devoted their resources to producing a range of military radio equipment required for the armed forces. This resulted in a shortage of consumer radio sets and spare parts, particularly valves, as all production was for the services. The war also prompted a shortage of radio repairmen, as virtually all of them were needed in the services to maintain vital radio and radar equipment. This meant it was very difficult for the average citizen to get a radio repaired, and with very few new sets available, there was a desperate need to overcome the problem.[4]

The government solved this by arranging for over forty radio manufacturers to produce sets to a standard design with as few components as possible consistent with the ability to source them. Earlier, the government had introduced the "Utility" brand to ensure that all clothing, which was rationed, was produced to a reasonable quality standard as, prior to its introduction, a lot of shoddy goods had appeared on the market; the brand was therefore adopted for this wartime radio.[3][1]

The Utility Set had limited reception on medium wave and lacked a longwave band to simplify the design. The tuning scale listed only BBC stations. After the war a version with LW was made available and modification kits to retrofit existing sets were marketed.[5]

About 175,000 sets were sold, at a price of £12 3s 4d each (Error when using {{Inflation}}: NaN, check parameters for non-numeric data: |value=Template:£sd (parameter 2).).[4] The set is sometimes characterized as the British equivalent of the German Volksempfänger ("Peoples' Receiver"); however there were dissimilarities. The Volksempfänger were radio sets designed to be inexpensive enough for any German citizen to purchase one but higher quality consumer radios were always available to Germans who could afford to pay higher prices. By contrast, the Utility Set was the only consumer radio receiver available for purchase on the British market for much of the latter part of the war.[6] Starting in June 1942, manufacture of consumer radio receivers in the United States also ceased due to military production needs.[7][8]

Specifications

The sets used a four-valve superhet circuit with an audio output of 4 watts at 10% total harmonic distortion; they performed as well as many pre-war sets. The valve complement consisted of a triode-hexode frequency mixer, a variable-μ RF pentode IF amplifier and a high slope output pentode. A "Westector" solid-state copper oxide diode was used for demodulation, which saved one valve and allowed use of an available type of pentode for the audio stage.[1] The HT line was derived from a full wave rectifier. All valves were on International Octal sockets apart from the rectifier which was on a British 4-pin base. There were minor variations between set makers; for instance Philips used IF transformers with adjustable ferrite cores (so-called slug tuning) rather than the conventional trimmer capacitors.[3]

Manufacturers

More than 40 manufacturers, such as Pye Ltd. and Marconiphone, made Utility radios. The manufacturer of a particular set was not readily apparent to the general public, although each manufacturer stamped a code letter on the radio to identify themselves to dealers. UK makers often used different designations for the same valve (tube), while octal tubes might be of USA origin. All valves in the Utility radio used standard designations prefixed by BVA (for British Radio Valve Manufacturers' Association). They were produced by valve makers such as Mullard, MOV, Cossor, Mazda and Brimar. Dealers, knowing the maker of a set and which valve manufacturer that maker used, could easily deduce which pre-war types these were and make warranty claims on the manufacturer.[5]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Miller, Charles Edward (2000). Valve Radio and Audio Repair Handbook. Newnes. pp. 144–151. ISBN 0-7506-3995-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=_DJZf2P0gFoC.

- ↑ "Wartime manufactuerers and sets". vintageradio.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. https://web.archive.org/web/20160303233134/http://www.vintage-radio.com/manufacturers-and-sets/wartime.html. Retrieved 2014-12-26.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Sean Street (2002). A Concise History of British Radio, 1922-2002. Kelly Publications. p. 78. ISBN 978-1-903053-14-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=y7jo0IcUZeoC&pg=PA78.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Wartime Civilian Receiver". ClassicWireless.co.uk. 2003. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. https://web.archive.org/web/20121011231913/http://www.classicwireless.btinternet.co.uk/warciva.htm. Retrieved 2017-01-11.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Wartime mains". Thevalvepage.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. https://web.archive.org/web/20160303192706/http://www.thevalvepage.com/radios/wartime/mains/warmains.htm. Retrieved 2006-03-04.

- ↑ Corey Ross (6 May 2010). Media and the Making of Modern Germany: Mass Communications, Society, and Politics from the Empire to the Third Reich. OUP Oxford. p. 1805. ISBN 978-0-19-161494-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=RxytXTsadScC&pg=PA1805.

- ↑ Michael A. McGregor; Paul D. Driscoll; Walter Mcdowell (8 January 2016). Head's Broadcasting in America: A Survey of Electronic Media. Taylor & Francis. p. 77. ISBN 978-1-317-34792-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=m6dYCwAAQBAJ&pg=PT77.

- ↑ Lee B. Kennett (1985). For the Duration...: The United States Goes to War, Pearl Harbor-1942. Scribner. ISBN 978-0-684-18239-1. https://archive.org/details/fordurationunite00kenn.[page needed]

External links

- Technical review by BBC Research Department, 1943

- Utility Set(1)

- Utility Set(2)

- Manufacturers and valve complement

- Government Surplus advertisement

- Civilian Wartime (Utility) Radio – Restoration on YouTube

|