Engineering:Whaling disaster of 1871

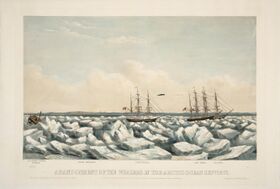

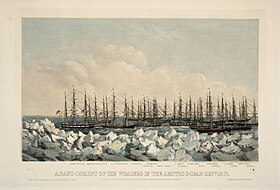

The whaling disaster of 1871 was an incident off the northern Alaskan coast in which a fleet of 33 American whaling ships were trapped in the Arctic ice in late 1871 and subsequently abandoned. It dealt a serious blow to the American whaling industry, already in decline.

The 1871 whaling season

In late June 1871, forty whaleships passed north through Bering Strait, hunting bowhead whales.[1] In mid-June the surviving crew of the whaleship Japan out of Melbourne, Victoria, which had been wrecked the previous year, were rescued and distributed among the fleet.[2] Lewis Kennedy, seaman, of the Japan died on board the Henry Taber.[3]

By August the vessels had passed as far as Point Belcher, near Wainwright, Alaska, before a stationary high, parked over northeast Siberia, reversed the normal wind pattern and pushed the pack ice toward the Alaskan coast. Seven ships were able to escape to the south, but 33 others were trapped. Within two weeks the pack had tightened around the vessels, crushing three ships - Comet on September 2, Roman on September 7, and Awashonks on September 8.[4] The crews were divided among the rest of the vessels. Some ships were jammed so close together that they could not swing clear of each other.[5]

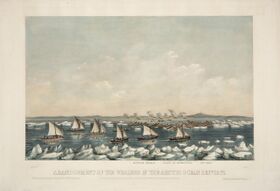

The remaining vessels were spread out in a long line, some 60 miles (97 km) south of Point Franklin.[6] On September 12 the masters met aboard Champion and agreed that, weather permitting, they would evacuate within the next few days.[7] Each master was to return to their ship and prepare whaleboats lightened of gear so that they could be slid across the ice between the open-water. The ships were strung-out over some 50 miles at this time, in open water in groups of three to five, separated by ice, but within sight of other ships. The signal of abandonment was to strike the American flag. On the morning of September 14 scout boats from the John Wells and Eugenia returned with the news of the rescue ships waiting to the south . After each of the ships struck their flag, the 1,219 people aboard the ships evacuated in small whaleboats with a three-month supply of provisions, crossed 70 miles (110 km) of ocean and ice, and were eventually brought to safety by the seven ships which had escaped the ice to the south.[4][8] Amazingly, there were no casualties. It was widely reported and accepted that a single crew member stayed on the Massachusetts through that winter, but his identify has been lost to history.[9]

The seven whalers that escaped took the following number of rescued whale men: the Europa (280), the Arctic (250), the Progress (221), the Lagoda (195), the Daniel Webster (113), the Midas (100), and the Chance (96).[1][10] They were forced to dump their catch and most of their equipment overboard to make room for passengers on the return trip to Honolulu.[4] The British barque Chance and the Hawaiian barque Arctic (Captain Tripp) presented the government of the USA with a claim for service rendered for $9520.[11][5]

The total loss was valued at over $1,600,000 ($34.15 million in today's dollars). Twenty-two of the wrecked vessels were from the Port of New Bedford in Massachusetts .[12] In 1872 the bark Minerva was discovered intact and subsequently salvaged,[13] but the rest were crushed in the ice, sank, or were stripped of wood by the local Inupiat.[8][14] It is reported that the Concordia, George Howland, and the Thomas Dickason, owned by George (Jr.) and Matthew Howland brothers, were not insured and represented 1/3 of their fleet.[9] There were about 200 American whaling ships and 20 British whaling ships in the Pacific and Arctic Oceans prior to this disaster.[15]

The role of the Chance

The firm of Messrs. Barron and Austin were the managing owners of the 320 ton British whaling barque Chance (out of Sydney, New South Wales), together with other owners.[10][16] It departed Sydney for a whaling voyage on 22 February 1871 under the command of Captain Thos. S. Norton with a chief officer, four mates and a crew of 28.[10][16][3] Fit-out prior to departure had cost £3200 or USD16000.[10] A spike in the price of sperm whale oil in 1870 prompted the owners of several Sydney whaling ships to form the Sydney Whaling Company in 1871 and issue a prospectus to raise capital to buy new vessels and improve their existing ones.[17] This prospectus valued the Chance, including insurance and the catch of its current [1871] voyage at £6,084.[15] Both Joseph Gerrish Barron and Solon Seneca Austin (Mesrs. Barron and Austin) were sea captains from the United States who were living in Sydney.[18][19][20] On 13 November 1872 the interests of that firm were transferred to the firm of Lane, Chester and Co. and the partnership of Barron and Austin was dissolved on 31 March 1873.[21][22]

The Chance arrived at the port of Honolulu in the Kingdom of Hawaii on 30 October 1871.[3] Captains J. H. Fisher and J. Silva of the barque Oliver Crocker and the brig Comet wrote a public letter expressing gratitude to the captain and officers of the Chance for the genuine hospitality received while on board.[3] The crew of the Japan were also on board.[2] On 27 July 1872 USD35 a head payment under the disabled and destitute sailors' act, for the support of the 96 rescued sailors while they were on board the Chance, was received from the U.S Government, after application was made by the ship's agents in Honolulu without the knowledge of the ship's owners.[23][10] After having repairs done in Honolulu, the Chance departed two weeks later intending to proceed to Sydney via the New Zealand whaling ground.[24] The barque arrived back in Sydney from Honolulu on 28 January 1872 with 150 barrels sperm, 150 barrels whale oil and 2,000 pounds (910 kg) bone instead of the 800 barrels of oil and 12,000 pounds (5,400 kg) bone that could have been expected.[25][10]

Barron and Austin first made a claim against the United States government for compensation for losses on 15 February 1872. In 1877, after intervention from the Earl of Derby, British Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, the process of putting the matter before the American Congress commenced.[10] After a Report was ordered printed on 31 March 1880 by the U.S House of Representatives, Benjamin W. Harris, of Massachusetts introduced a bill in December 1881 for the relief of the owners, officers, and crew of the British bark Chance to the U.S Congress; which was read a first and second time, referred to the Committee on Foreign Affairs, and ordered to be printed.[26] By 1886 the Bill for the relief of the owners, officers and crew (who would have all received a proportion of the value of the catch[10]) of the Chance had made it to the Senate where the Senate agreed to increasing the sum from $10,000 to $15,500 to allow for fifteen years' interest. The break with the tradition of not allowing interest was because the funds were owed to foreign people. The Bill was read a third time and passed.[23] The Bill was signed by the President of the United States in April 1890, almost nineteen years after the event.[27] Of the USD16,000 compensation paid, £2448 7s 2d was paid to the Government of New South Wales to pay to the owners, officers and crew of the Chance.[28]

Lost whaling vessels

The lost vessels were as follows:[12][9]

| Vessel | Homeport | Captain[9] | Est Vessel value[9] | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Awashonks | New Bedford, MA | Ariel Norton | $58,000 | Crushed in the ice on September 8, 1871.[1] |

| Concordia | New Bedford, MA | Robert Jones | $75,000 | Abandoned and lost. Wreck burned by Inuit.[9][29] This ship was on its maiden voyage |

| Contest | New Bedford, MA | Leander C. Owen | $40,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Elizabeth Swift | New Bedford, MA | George W. Bliven | $60,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Emily Morgan | New Bedford, MA | Benjamin Dexter | $60,000 | Abandoned and lost. Wreck later found ashore.[9] |

| Eugenia | New Bedford, MA | Daniel B. Nye | $56,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Fanny | New Bedford, MA | Lewis W. Williams | $58,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Gay Head | New Bedford, MA | William H. Kelley | $40,000 | Abandoned and lost. Wreck burned by Inuit.[9][29] |

| George | New Bedford, MA | Abraham Osborn | $40,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| George Howland | New Bedford, MA | James H. Knowles | $43,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Henry Taber | New Bedford, MA | Timothy C. Packard | $52,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| John Wells | New Bedford, MA | Aaron Dean | $40,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Massachusetts | New Bedford, MA | West Mitchell | $46,000 | Abandoned and wrecked. A lone sailor remained with the wreck through the winter. |

| Minerva | New Bedford, MA | Hezekiah Allen | $50,000 | Abandoned. Discovered intact in 1872; manned and taken south.[13] |

| Navy | New Bedford, MA | George F. Bouldry | $48,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Oliver Crocker | New Bedford, MA | James H. Fisher | $48,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Reindeer | New Bedford, MA | B. F. Loveland | $40,000 | Abandoned and lost. Sunken wreck found in 1872.[29] |

| Roman | New Bedford, MA | Jared Jernegan | $60,000 | Crushed in the ice on September 7, 1871.[1] |

| Seneca | New Bedford, MA | Edmund Kelley | $70,000 | Abandoned and lost. Beached wreck found in 1872.[9][29] |

| Thomas Dickason | New Bedford, MA | Valentine Lewis | $50,000 | Abandoned and lost. Wreck found in 1872.[9][29] |

| William Rotch | Honolulu, HI | Benjamin D. Whitney | $43,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Monticello | New London, CT | Thomas W. Williams | $45,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| J.D. Thompson | New London, CT | Capt. Allen | $45,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Carlotta | San Francisco, CA | E. Everett Smith | $52,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Florida | San Francisco, CA | D. R. Fraser | $51,000 | Abandoned and lost. Wreck burned by Inuit.[9][29] |

| Victoria | San Francisco, CA | Capt. Redfield | $30,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Comet | Honolulu, HI | Capt. J. Silva (possibly Joseph D Silva) | $20,000 | Crushed in the ice on September 2, 1871.[1][3] |

| Julian | Honolulu, HI | John Heppingstone | $40,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Kohola | Honolulu, HI | Alexander Almy | $20,000 | Abandoned and lost. Wreck later found ashore.[9] |

| Paiea | Honolulu, HI | Capt. Newbury | $20,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

| Champion | Edgartown, MA | Henry Pease | $40,000 | Abandoned and lost. Wreck later found ashore.[9] |

| Mary | Edgartown, MA | Edward P. Herendeen | $57,000 | Abandoned and lost. |

Two of the wrecks located (2015)

In 2015, NOAA funded a research expedition entitled "The Search for the Lost Whaling Fleets of the Western Arctic".[30] One hundred forty-four years after the disaster, acoustic mapping of the ocean floor detected the wrecks of two whaleships that were "remarkably well preserved".[31][32] Visualized details of anchors, fasteners, ballast, and the brick-lined try-pots positively identified them as 19th century whalers. Although many whaleships hunted in those waters, the expedition archeologist and co-director Dr. Brad Barr believes that they are wrecks from the 1871 disaster, as it is the same area where whaleship planks washed up on shore for many years after 1871. The identity of the two wrecks is currently not known. Due to the shallow depths of the survey area (average depth was 28 feet), it is thought by the expedition leaders that the other wrecks were destroyed over time by the action of the sea. The site is protected under Historic Protection Laws of the United States, and NOAA has not released the precise location to the general public. Dr. Barr was hopeful that expeditions by other marine archeologists could do a more complete survey of the wrecks some time in the future, possibly even identifying them, but NOAA will likely not return to the area again.

See also

- Whale oil

- Overland Relief Expedition

Further reading

Nichols, Peter (2009). Final Voyage: A Story of Arctic Disaster and One Fateful Whaling Season (Oil and Ice: A Story of Arctic Disaster and the Rise and Fall of America's Last Whaling Dynasty ed.). Putnam. ISBN 978-0-399-15602-1. https://archive.org/details/finalvoyagestory00nich.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Alexander Starbuck. History of the American Whale Fishery grom its Earliest Inception to the Year 1876. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office. http://mysite.du.edu/~ttyler/ploughboy/starbuck.htm.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "The Cruise and shipwreck of the 'Japan'". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser XVI (20). November 11, 1871. ISSN 2332-0656. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015418/1871-11-11/ed-1/seq-4/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 "A Winter in the Arctic". The Pacific Commercial Advertiser XVXI (19): p. 2. November 4, 1871. ISSN 2332-0656. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn82015418/1871-11-04/ed-1/seq-2/.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Paul Edward Parker. "Study focuses on end of whaling for city". http://archive.southcoasttoday.com/daily/08-98/08-04-98/c01li066.htm.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "The Very Latest from the Arctic FLeet!". The Hawaiian Gazette VII (41): p. 22. October 25, 1871. ISSN 2157-1392. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025121/1871-10-25/ed-1/seq-2/.

- ↑ "The Whaling Disaster of 1871". http://www.marinearts.com/Pages/rfweisswhalingdisaster.htm.

- ↑ Allen, Everett S. (1983). Children of the Light. Little Brown & Company. ISBN 0-940160-23-4.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Robert McKenna (July 2003). The Dictionary of Nautical Literacy. McGraw Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-143642-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=R8bmQL-ijCMC&q=whaling+%2B1871+%2Bice+%2Btrapped+%2Bcrushed+%2BAlaska&pg=PA147.

- ↑ 9.00 9.01 9.02 9.03 9.04 9.05 9.06 9.07 9.08 9.09 9.10 9.11 9.12 Everett S. Allen. Children of the Light. (Parnassus Imprints, 1983.)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 Reports of Committees: 16th Congress, 1st Session - 49th Congress, 1st Session. III. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office. 1880. Report No. 671. https://books.google.com/books?id=Oq0FAAAAQAAJ&dq=%22british+bark+chance%22&pg=PA672. Retrieved 26 November 2022.

- ↑ "Washington: The Committee on Foreign Affairs". The New York Herald (((12,899))): p. 3. December 15, 1871. ISSN 2474-3224. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83030313/1871-12-15/ed-1/seq-3/.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Overview of American Whaling: Arctic Whaling". http://www.whalingmuseum.org/library/amwhale/am_arctic.html.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 John Randolph Spears (1908). The Story of the New England Whalers. The Macmillan Company. p. 403. https://archive.org/details/storynewengland01speagoog. "Bark Roman."

- ↑ "Honolulu". The Sydney Morning Herald LXVI (((10,802))): p. 4. 31 December 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28412352.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald LXIV (((10,351))): p. 8. 24 July 1871. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13242223.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Departures—January 31". Empire (5991): p. 3. 24 February 1871. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article63116279.

- ↑ Mark Howard (2011). "Sydney's whaling fleet". The Dictionary of Sydney. https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/sydneys_whaling_fleet. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ↑ "Personal". The Daily Telegraph (Sydney) (9982): p. 9. 25 May 1911. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article239095048.

- ↑ "Central Police Court". Sydney Mail VI (265): p. 4. 29 July 1865. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article166661507.

- ↑ "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald LXI (9935): p. 1. 25 March 1870. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13202529.

- ↑ "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald LXVI (((10,762))): p. 6. 14 November 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13322423.

- ↑ "Advertising". The Sydney Morning Herald LXVII (((10,880))): p. 1. 1 April 1873. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article28413012.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 "The British Bark Chance". Congressional Record: 5803. 17 June 1886. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1886-pt6-v17/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1886-pt6-v17-8.pdf#page=7.

- ↑ "Shipping News". The Hawaiian Gazette VII (44): p. 3. November 15, 1871. ISSN 2157-1392. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83025121/1871-11-15/ed-1/seq-3/.

- ↑ "Imports—January 27". The Sydney Morning Herald LXV (((10,513))): p. 4. 29 January 1872. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13251566.

- ↑ "British Bark Chance". Congressional Record: 111. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GPO-CRECB-1882-pt1-v13/pdf/GPO-CRECB-1882-pt1-v13-7.pdf#page=37.

- ↑ "Bills Signed by the President". The Evening Bulletin: p. 4. April 2, 1890. ISSN 2157-488X. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn87060190/1890-04-02/ed-1/seq-4/.

- ↑ "Parliament". Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners' Advocate (6529): p. 5. 18 September 1895. http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article132520014.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 29.5 United States Commission of Fish and Fisheries: Part IV: Report of the Commissioner 1875–1876. Washington DC: US Government Printing Office. 1878. https://books.google.com/books?id=DMwEAAAAQAAJ&q=Minerva+%2B%22Wainwright+Inlet%22&pg=RA1-PA109.

- ↑ "Search for the Lost Whaling Fleets of the Western Arctic" (in EN-US). https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/15lostwhalingfleets/welcome.html.

- ↑ "Remains of lost 1800s whaling fleet discovered off Alaska's Arctic coast". 6 January 2016. https://www.noaa.gov/media-release/remains-of-lost-1800s-whaling-fleet-discovered-off-alaska-s-arctic-coast.

- ↑ Ofgang, Erik. "Dramatic Discovery of Two Whaleships Lost in Arctic for 144 Years Sheds Light on CT's Whaling History" (in en). Connecticut Magazine. https://www.connecticutmag.com/the-connecticut-story/dramatic-discovery-of-two-whaleships-lost-in-arctic-for-144-years-sheds-light-on-ct/article_b5f955c2-9488-5930-b5b5-7277ada0e1d0.html. Retrieved 2021-03-21.

External links

|