Epicurus' paradox

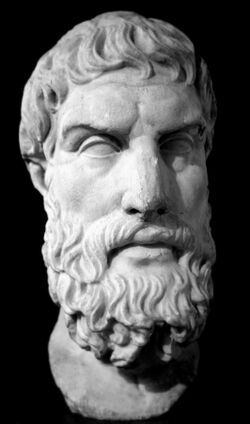

The Epicurus paradox is a logical dilemma about the problem of evil attributed to the Greek philosopher Epicurus, who argued against the existence of a god who is simultaneously omniscient, omnipotent and omnibenevolent.

The paradox

The logic of the paradox proposed by Epicurus takes three possible characteristics of a god (omnipotence, omniscience, and omnibenevolence—complete power, knowledge, and benevolence) and pairs the concepts together. It is postulated that in each pair, if the two members are true, the missing member cannot also be true, making the paradox a trilemma. The paradox also theorizes how if it is illogical for one of the characteristics to be true, then it cannot be the case that a god with all three exists.[1] The pairs of the characteristics and their potential contradictions they would create consist of the following:

- If a knows everything and has unlimited power, then they have knowledge of all evil and have the power to put an end to it. But if they do not end it, they are not completely benevolent.

- If a god has unlimited power and is completely good, then they have the power to extinguish evil and want to extinguish it. But if they do not do it, their knowledge of evil is limited, so they are not all-knowing.

- If a god is all-knowing and totally good, then they know of all the evil that exists and wants to change it. But if they do not, which must be because they are not capable of changing it, so they are not omnipotent.

God in Epicureanism

Epicurus was not an atheist, although he rejected the idea of a god concerned with human affairs; followers of Epicureanism denied the idea that there was no god. While the conception of a supreme, happy and blessed god was the most popular during his time, Epicurus rejected such a notion, as he considered it too heavy a burden for a god to have to worry about all the problems in the world. For this reason, Epicureanism postulates that gods would not have any special affection for human beings and would not know of their existence, serving only as moral ideals that humanity could try to get closer to.[2] Epicurus came to the conclusion that the gods could not be concerned with the well-being of humanity through observing the problem of evil; that is, the presence of suffering on earth.

Attribution and variations

There is no text by Epicurus that confirms his authorship of the argument.[3] Therefore, although it was popular with the skeptical school of Greek philosophy, it is possible that Epicurus' paradox was wrongly attributed to him by Lactantius who, from his Christian perspective, while attacking the problem proposed by the Greek, would have considered him an atheist. There is a suggestion that it was in fact the work of a skeptical philosopher who preceded Epicurus, possibly Carneades. German scholar Reinhold F. Glei believes that the theodicy argument is from a non-Epicurean or anti-Epicurean academic source.[4] The oldest preserved version of this trilemma appears in the writings of the skeptic Sextus Empiricus.

Charles Bray, in his book The Philosophy of Necessity of 1863, quotes Epicurus without mentioning his source as the author of the following excerpt:

Would God be willing to prevent evil but unable? Therefore he is not omnipotent. Would he be capable, but without desire? So he is malevolent. Would he be both capable and willing? So why is there evil?

N. A. Nicholson, in his Philosophical Papers of 1864, attributes "the famous inquiries" to Epicurus, using words previously phrased by Hume. Hume's phrase occurs in the tenth book of his acclaimed Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion, published posthumously in 1779. The character Philo begins his speech by saying "Epicurus' ancient questions remain unanswered". Hume's quote comes from Pierre Bayle's influential Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, which quotes Lactantius attributing the questions to Epicurus. This attribution occurs in chapter 13 of Lactantius's "De Ira Dei", which provides no sources.

Hume postulates:

[God's] power is infinite: whatever he desires is executed. But neither man nor any other animal is happy. Therefore he does not want your happiness. His wisdom is infinite: he never errs in choosing the means to any end: but the course of nature tends to be contrary to any human or animal happiness: therefore it is not established for such a purpose. Throughout the entire history of human knowledge, there are no more certain and infallible inferences than these. In what point, therefore, do your benevolence and mercy remind you of the benevolence and mercy of men?

See also

References

- ↑ Mark Joseph Larrimore, (2001), The Problem of Evil, pp. xix-xxi. Wiley-Blackwell

- ↑ Mark Joseph Larrimore, The Problem of Evil: a reader, Blackwell (2001), pp. xx.

- ↑ Reinhold F. Glei, Et invidus et inbecillus. Das angebliche Epikurfragment bei Laktanz, De ira dei 13,20-21, in: Vigiliae Christianae 42 (1988), pp. 47-58

- ↑ Sexto Empírico, Outlines of Pyrrhonism, 175: "those who firmly maintain that god exists will be forced into impiety; for if they say that he [god] takes care of everything, they will be saying that god is the cause of evils, while if they say that he takes care of some things only or even nothing, they will be forced to say that he is either malevolent or weak"

- ↑ Lucius Caecilius Firmianus Lactantius (1532). Divinae institutiones. VII. [S.l.: s.n.]

External links

- ↑ Tooley, Michael (2021), Zalta, Edward N., ed., The Problem of Evil (Winter 2021 ed.), Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/evil/, retrieved 2023-12-11

- ↑ "Epicurus | Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy" (in en-US). https://iep.utm.edu/epicur/.

- ↑ P. McBrayer, Justin (2013) (in En). The Blackwell companion to the problem of evil. Malden, MA: Wiley Blackwell.

- ↑ Glei, Reinhold (1988). "Et invidus et inbecillus. Das angebliche Epikurfragment bei Laktanz, de ira dei 13,20-21". Vigiliae Christianae 42 (1): 47–58. doi:10.2307/1584470.

|