Ex-tangential quadrilateral

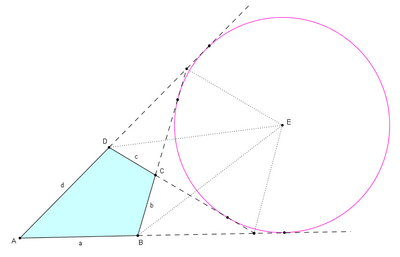

In Euclidean geometry, an ex-tangential quadrilateral is a convex quadrilateral where the extensions of all four sides are tangent to a circle outside the quadrilateral.[1] It has also been called an exscriptible quadrilateral.[2] The circle is called its excircle, its radius the exradius and its center the excenter (E in the figure). The excenter lies at the intersection of six angle bisectors. These are the internal angle bisectors at two opposite vertex angles, the external angle bisectors (supplementary angle bisectors) at the other two vertex angles, and the external angle bisectors at the angles formed where the extensions of opposite sides intersect (see the figure to the right, where four of these six are dotted line segments). The ex-tangential quadrilateral is closely related to the tangential quadrilateral (where the four sides are tangent to a circle).

Another name for an excircle is an escribed circle,[3] but that name has also been used for a circle tangent to one side of a convex quadrilateral and the extensions of the adjacent two sides. In that context all convex quadrilaterals have four escribed circles, but they can at most have one excircle.[4]

Special cases

Kites are examples of ex-tangential quadrilaterals. Parallelograms (which include squares, rhombi, and rectangles) can be considered ex-tangential quadrilaterals with infinite exradius since they satisfy the characterizations in the next section, but the excircle cannot be tangent to both pairs of extensions of opposite sides (since they are parallel).[4] Convex quadrilaterals whose side lengths form an arithmetic progression are always ex-tangential as they satisfy the characterization below for adjacent side lengths.

Characterizations

A convex quadrilateral is ex-tangential if and only if there are six concurrent angles bisectors. These are the internal angle bisectors at two opposite vertex angles, the external angle bisectors at the other two vertex angles, and the external angle bisectors at the angles formed where the extensions of opposite sides intersect.[4]

For the purpose of calculation, a more useful characterization is that a convex quadrilateral with successive sides a, b, c, d is ex-tangential if and only if the sum of two adjacent sides is equal to the sum of the other two sides. This is possible in two different ways—either as

or

This was proved by Jakob Steiner in 1846.[5] In the first case, the excircle is outside the biggest of the vertices A or C, whereas in the second case it is outside the biggest of the vertices B or D, provided that the sides of the quadrilateral ABCD are a = AB, b = BC, c = CD, and d = DA. A way of combining these characterizations regarding the sides is that the absolute values of the differences between opposite sides are equal for the two pairs of opposite sides,[4]

These equations are closely related to the Pitot theorem for tangential quadrilaterals, where the sums of opposite sides are equal for the two pairs of opposite sides.

Urquhart's theorem

If opposite sides in a convex quadrilateral ABCD intersect at E and F, then

The implication to the right is named after L. M. Urquhart (1902–1966) although it was proved long before by Augustus De Morgan in 1841. Daniel Pedoe named it the most elementary theorem in Euclidean geometry since it only concerns straight lines and distances.[6] That there in fact is an equivalence was proved by Mowaffac Hajja,[6] which makes the equality to the right another necessary and sufficient condition for a quadrilateral to be ex-tangential.

Comparison with a tangential quadrilateral

A few of the metric characterizations of tangential quadrilaterals (the left column in the table) have very similar counterparts for ex-tangential quadrilaterals (the middle and right column in the table), as can be seen in the table below.[4] Thus a convex quadrilateral has an incircle or an excircle outside the appropriate vertex (depending on the column) if and only if any one of the five necessary and sufficient conditions below is satisfied.

| Incircle | Excircle outside of A or C | Excircle outside of B or D |

|---|---|---|

The notations in this table are as follows: In a convex quadrilateral ABCD, the diagonals intersect at P. R1, R2, R3, R4 are the circumradii in triangles ABP, BCP, CDP, DAP; h1, h2, h3, h4 are the altitudes from P to the sides a = AB, b = BC, c = CD, d = DA respectively in the same four triangles; e, f, g, h are the distances from the vertices A, B, C, D respectively to P; x, y, z, w are the angles ABD, ADB, BDC, DBC respectively; and Ra, Rb, Rc, Rd are the radii in the circles externally tangent to the sides a, b, c, d respectively and the extensions of the adjacent two sides for each side.

Area

An ex-tangential quadrilateral ABCD with sides a, b, c, d has area

Note that this is the same formula as the one for the area of a tangential quadrilateral and it is also derived from Bretschneider's formula in the same way.

Exradius

The exradius for an ex-tangential quadrilateral with consecutive sides a, b, c, d is given by[4]

where K is the area of the quadrilateral. For an ex-tangential quadrilateral with given sides, the exradius is maximum when the quadrilateral is also cyclic (and hence an ex-bicentric quadrilateral). These formulas explain why all parallelograms have infinite exradius.

Ex-bicentric quadrilateral

If an ex-tangential quadrilateral also has a circumcircle, it is called an ex-bicentric quadrilateral.[1] Then, since it has two opposite supplementary angles, its area is given by

which is the same as for a bicentric quadrilateral.

If x is the distance between the circumcenter and the excenter, then[1]

where R and r are the circumradius and exradius respectively. This is the same equation as Fuss's theorem for a bicentric quadrilateral. But when solving for x, we must choose the other root of the quadratic equation for the ex-bicentric quadrilateral compared to the bicentric. Hence, for the ex-bicentric we have[1]

From this formula it follows that

which means that the circumcircle and excircle can never intersect each other.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Radic, Mirko; Kaliman, Zoran and Kadum, Vladimir, "A condition that a tangential quadrilateral is also a chordal one", Mathematical Communications, 12 (2007) pp. 33–52.

- ↑ Bogomolny, Alexander, "Inscriptible and Exscriptible Quadrilaterals", Interactive Mathematics Miscellany and Puzzles, [1]. Accessed 2011-08-18.

- ↑ K. S. Kedlaya, Geometry Unbound, 2006

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Josefsson, Martin, Similar Metric Characterizations of Tangential and Extangential Quadrilaterals, Forum Geometricorum Volume 12 (2012) pp. 63-77 [2]

- ↑ F. G.-M., Exercices de Géométrie, Éditions Jacques Gabay, sixiéme édition, 1991, p. 318.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hajja, Mowaffaq, A Very Short and Simple Proof of “The Most Elementary Theorem” of Euclidean Geometry, Forum Geometricorum Volume 6 (2006) pp. 167–169 [3]