Finance:Goal-based investing

Goals-Based Investing or Goal-Driven Investing (sometimes abbreviated GBI) is the use of financial markets to fund goals within a specified period of time. Traditional portfolio construction balances expected portfolio variance with return and uses a risk aversion metric to select the optimal mix of investments. By contrast, GBI optimizes an investment mix to minimize the probability of failing to achieve a minimum wealth level within a set period of time. Goals-based investors have numerous goals (known as the "goals-space") and capital is allocated across these goals as well as to investments within them. Following Maslow's hierarchy of needs, more important goals (e.g. survival needs: food, shelter, medical care) receive priority over less important goals (e.g. aspirational goals such as buying a vacation home or yacht).[1] Once capital is divvied among an investor's goals, the portfolios are optimized to deliver the highest probability of achieving each specified goal. It is a similar approach to asset-liability management for insurance companies and the liability-driven investment strategy for pension funds, but GBI further integrates financial planning with investment management which insures that household goals are funded in an efficient manner.

In goals-based investing, assets are the full set of resources the investor has available (including financial assets, real estate, employment income, social security, etc.) while liabilities are the financial liabilities (such as loans, mortgages, etc) in addition to the capitalized value of the household's financial goals and aspirations. GBI takes into account the progress against goals which are categorized as either essential needs, lifestyle wants or legacy aspirations depending on level of importance to an individual or family.[2] It also helps to prevent rash investment decisions by providing a clear process for identifying goals and choosing investment strategies for those goals. These goals may include ability to put children in a good school, retiring early, and be able to afford a quality life after retirement.

Mathematical model

Source:[3]

Goals-based investors are typically assumed to have a collection goals which compete for a limited pool of wealth. This set of goals, [math]\displaystyle{ \mathsf{G} }[/math], is called the goals-space and is rank-ordered such that [math]\displaystyle{ \{A,B,C,...,N\}\in \mathsf{G} }[/math], where goal [math]\displaystyle{ A }[/math] is preferred to goal [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math], goal [math]\displaystyle{ B }[/math] is preferred to goal [math]\displaystyle{ C }[/math] and so on, across the total number of goals, [math]\displaystyle{ N }[/math]. Mathematically, a goal is defined as a three-variable vector, [math]\displaystyle{ A=(w,W,t) }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] is the current wealth dedicated to the goal, [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math] is the future wealth required to fund the goal, and [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] is the time period in which the objective must be funded. [math]\displaystyle{ W }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ t }[/math] are given by the investor; [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math] is an output of the across-goal optimization procedure. Current wealth, [math]\displaystyle{ w }[/math], could be also thought of as the percentage of overall wealth an investor dedicates to the goal. Because of this definition, the goal vector can be equivalently stated as [math]\displaystyle{ A=(\varpi\vartheta,W,t) }[/math] with [math]\displaystyle{ \varpi }[/math] representing the total pool of wealth available to the investor and [math]\displaystyle{ \vartheta }[/math] representing the percentage of the total wealth pool allocated to this particular goal (of course, [math]\displaystyle{ \sum_i \vartheta_i=1 }[/math]).

Because preferences across the goals-space can be declared, there exists a value function such that [math]\displaystyle{ A\succeq B \implies v(A)\geq v(B) }[/math]. It is therefore the objective of the investor to maximize utility by varying the allocation of wealth to each goal in the goals-space, and vary the allocation of wealth to potential investments within each goal:

[math]\displaystyle{ \max_{\vartheta,\omega} \sum_i^N v(i)\phi(\varpi\vartheta_i, W_i, t_i) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \phi(\cdot) }[/math] is the probability of achieving a goal, given the inputs. In most theoretical applications, [math]\displaystyle{ \phi(\cdot) }[/math] is assumed Gaussian (though any distribution model that fits the application may be used), and [math]\displaystyle{ \phi(\varpi\vartheta,W,t) }[/math] usually takes the form

[math]\displaystyle{ \phi(\varpi\vartheta,W,t) = 1 - \Phi\left( \frac{W}{\varpi\vartheta}^{\frac{1}{t}}-1; \mu, \sigma\right) }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \Phi(\cdot) }[/math] is the Gaussian cumulative distribution function, [math]\displaystyle{ \frac{W}{\varpi\vartheta}^{\frac{1}{t}}-1 }[/math] is the return required to achieve the portfolio's objective within the given time period, and [math]\displaystyle{ \mu }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] are the expected return and standard deviation of the investment portfolio. Expected returns and volatility are themselves functions of the portfolio's investment weights:

[math]\displaystyle{ \mu = \sum_i \omega_i m_i }[/math]

[math]\displaystyle{ \sigma^2 = \sum_i \omega^2_i s_i ^2 + \sum_i \sum_{i\neq j}\omega_i\omega_j s_i s_j\rho_{i,j} }[/math]

with [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math] representing the investment's expected return, [math]\displaystyle{ s }[/math] representing the investment's expected standard deviation, and [math]\displaystyle{ \rho_{i,j} }[/math] representing the correlation of investment [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] to investment [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math].

The implementation of the model carries some complexity as it is recursive. The probability of achieving a goal is dependent on the amount of wealth allocated to the goal as well as the mix investments within each goal's portfolio. The mix of investments, however, is dependent on the amount of wealth dedicated to the goal. To overcome this recursivity the optimal mix of investments can first be found for discrete levels of wealth allocation, then a Monte Carlo engine can be used to find maximal utility.

Comparison to modern portfolio theory

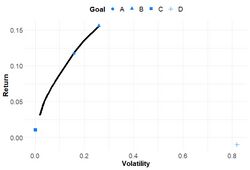

The fundamental difference between goals-based investing and modern portfolio theory (MPT) turns on the definition of "risk." MPT defines risk as portfolio volatility whereas GBI defines risk as the probability of failing to achieve a goal. Initially, it was thought that these competing definitions were mutually-exclusive,[4] though it was later shown that the two are mathematically synonymous for most cases.[5] In the case where investors are not limited in their ability to borrow or sell short, there is no cost to dividing wealth across various accounts,[6] nor is there a mathematical difference between mean-variance optimization and probability maximization. However, goals-based investors are generally assumed to be limited in their ability to borrow and sell short. Under those real-world constraints, the efficient frontier has an endpoint and probability maximization produces different results than mean-variance optimization when a portfolio's required return ([math]\displaystyle{ r_{req.} }[/math]) is greater than the maximum return offered by the mean-variance efficient frontier ([math]\displaystyle{ \mu_e }[/math]). This is because when [math]\displaystyle{ r_{req.}\gt \mu_e }[/math] probability is maximized by increasing variance rather than minimizing it. MPT's quadratic utility form [math]\displaystyle{ u=r-\frac{\gamma}{2}\sigma^2, \gamma\gt 0 }[/math] assumes investors are always variance averse whereas GBI expects investors to be variance seeking when [math]\displaystyle{ r_{req.}\gt \mu_e }[/math], variance averse when [math]\displaystyle{ r_{req.}\lt \mu_e }[/math], and variance indifferent when [math]\displaystyle{ r_{req.}= \mu_e }[/math]. Mean-variance portfolios are therefore first-order stochastically dominated by goals-based portfolios when short-sales and leverage are bounded.

In its pure form, modern portfolio theory takes no account of investor goals. Rather, MPT portfolios are selected using an investor's variance aversion parameter, [math]\displaystyle{ \gamma }[/math], and no account is taken of future wealth requirements, current wealth available, nor the time horizon within which the goals must be attained. MPT has since been adapted to include these variables, but goals-based portfolio solutions yield higher probabilities of goal achievement than adapted MPT.

For most applications, mean-variance optimized portfolios and goals-based portfolios are the same. For aspirational goals, where an investor has allocated little initial wealth, goals-based portfolios will favor high-variance investments that would be eliminated from a mean-variance efficient portfolio.

History and development

Goals-based investing grew out of observations made by behavioral finance and ongoing critiques of modern portfolio theory (MPT). Richard Thaler's observation that individuals tend to mentally subdivide their wealth, with each mental "bucket" dedicated to different objectives (a concept called mental accounting) was foundational to the later development of GBI. Indeed, some authors refer to goals-based portfolios as "mental accounts." Other authors began to critique MPT as not as effective when applied to individuals, especially in light of taxes.[7][8]

Behavioral portfolio theory (BPT) combined mental accounting with the redefinition of risk as the probability of failing to achieve a goal,[4] and investors balance returns over-and-above their requirement with the risk of failing to achieve the goal. BPT also revealed a problem with adapting MPT. While most practitioners were building investment portfolios wherein the portfolio's expected return equaled the required return required to achieve the goal, BPT showed that this necessarily results in a 50% probability of achieving the goal.[2] The probability maximization component of goals-based investing was therefore adopted from behavioral portfolio theory.

Early critics of this approach suggested that divvying wealth across separate portfolios may generate inefficient mean-variance portfolios. It was eventually shown, however, that this physical manifestation of the mental accounting framework was not necessarily inefficient, so long as short-sales and leverage were allowed. As long as all portfolios reside on the mean-variance efficient frontier, then the aggregate portfolio will reside on the frontier as well.[6]

Other researchers further questioned the use of MPT when applied to individuals because the risk-aversion parameter was shown to vary through time and in response to different objectives. As Carrie H. Pan and Meir Statman put it: "foresight is different from hindsight, and the risk tolerance of investors, assessed in foresight, is likely different from their risk tolerance assessed in hindsight."[9] MPT was synthesized with behavioral portfolio theory, and in that synthesis work the risk-aversion parameter was eliminated. Rather than assess her risk aversion parameter, the investor is asked to specify the maximum probability of failure she is willing to accept for a given goal. This probability figure is then mathematically converted into MPT's risk aversion parameter and portfolio optimization proceeds along mean-variance lines.[5] The synthesis work, then, eliminated the risk-is-failure-probability of original behavioral portfolio theory and thus yielded infeasible solutions when the required return was greater than the portfolio's expected return.

In addressing how investors should allocate wealth across goals, Jean Brunel observed that the declaration of a maximum probability of failure was mathematically synonymous to the declaration of a minimum mental account allocation.[2] Investors, then, could allocate both within and across mental accounts, but some conversation was still required to allocate any remaining excess wealth.

To solve the infeasibility problem of the synthesized MPT, as well the problem of allocating "excess wealth," the original probability maximization component of BPT was resurrected and the value-of-goals function was introduced. Investors, then, face a two-layer allocation decision: allocating wealth across goals and allocating to investments within each goal.

In an effort to promote goals-based investing research, The Journal of Wealth Management was formed in 1998.

Goal-based Investing in Practice

The key challenge for goal-based investing (GBI) is to implement dedicated investment solutions aiming to generate the highest possible probability of achieving investors’ goals, and a reasonably low expected shortfall in case adverse market conditions make it unfeasible to achieve those goals. Modern Portfolio Theory or standard portfolio optimisation techniques are not suitable to solve this problem.

Deguest, Martellini, Milhau, Suri and Wang (2015),[10] introduce a general operational framework, which formalises the goals-based risk allocation approach to wealth management proposed in Chhabra (2005),[11] and which allows individual investors to optimally allocate to categories of risks they face across all life stages and wealth segments so as to achieve personally meaningful financial goals. One key feature in developing the risk allocation framework for goals-based wealth management includes the introduction of systematic rule-based multi-period portfolio construction methodologies, which is a required element given that risks and goals typically persist across multiple time frames. Academic research has shown that an efficient use of the three forms of risk management (diversification, hedging and insurance) is required to develop an investment solution framework dedicated to allowing investors to maximise the probabilities of reaching their meaningful goals given their dollar and risk budgets. As a result, the main focus of the framework is on the efficient management of rewarded risk exposures.

GBI strategies aim to secure investors' most important goals (labelled as “essential”, i.e. affordable and secure goals), while also delivering a reasonably high chance of success for achieving other goals, including ambitious ones which cannot be fully funded together with the most essential ones (and which are referred to as “aspirational”). Holding a leverage-constrained exposure to a well-diversified performance-seeking portfolio (PSP) often leads to modest probabilities of achieving such ambitious goals, and individual investors may increase their chances of meeting these goals by holding aspirational assets which generally contain illiquid concentrated risk exposures, for example under the form of equity ownership in a private business.

The goals-based wealth management framework includes two distinct elements. On the one hand, it involves the disaggregation of investor preferences into groups of goals that have similar key characteristics, with priority ranking and term structure of associated liabilities, and on the other hand it involves the mapping of these groups to optimised performance or hedging portfolios possessing corresponding risk and return characteristics, as well as an efficient allocation to such performance and hedging portfolios. More precisely, the framework involves a number of objective and subjective inputs, as well as a number of building block and asset allocation outputs, all of which are articulated within a five-step process:

1. Objective Inputs - Realistic Description of Market Uncertainty

2. Subjective Inputs - Detailed Description of Investor Situation

3. Building Block Outputs - Goal-Hedging and Performance-Seeking Portfolios

4. Asset Allocation Outputs - Dynamic Split Between Risky and Safe Building Blocks

5. Reporting Outputs - Updated Probabilities of Reaching Goals

Goal-Based Investing for the Retirement Problem

In most developed countries, pension systems are being threatened by rising demographic imbalances as well as lower growth in productivity. With the need to supplement public and private retirement benefits via voluntary contributions, individuals are becoming increasingly responsible for their own retirement savings and investment decisions.

The principles of goal-based investing can be applied to the retirement problem (Giron, Martellini, Milhau, Mulvey, and Suri, 2018).[12] In retirement investing, the goal is to generate replacement income. The first step is the identification of a safe “goal-hedging portfolio” (GHP), which effectively and reliably secures an investor’s essential goal, regardless of assumptions on parameter values such as risk premia on risky assets. In other words, the GHP should secure the purchasing power of retirement savings in terms of replacement income, an objective that is clearly different from securing the nominal value of retirement savings.

A target level of replacement income that the investor would like to reach but is unable to secure given current resources is said to be an aspirational goal. On the other hand, an essential goal is an affordable level of income that the investor would like to secure with the highest confidence level. In most cases, current savings are insufficient to finance the target income level that allow the desired standard of living to be financed, so the investor needs to have access to upside potential via some performance seeking portfolio (PSP). It can be shown that the optimal payoff can be approximated with a simple dynamic GBI strategy in which the dollar allocation to the PSP is given by a multiple of the risk budget, defined as the distance between current savings and a floor equal to the present value of the essential goal.

This form of strategy is reminiscent of the dynamic core-satellite investment approach of Amenc, Malaise, and Martellini (2004),[13] with the GHP as the core and the PSP as the satellite. It allows the tracking error with respect to the replacement income portfolio to be managed in a non-symmetric way, by capturing part of the upside of the PSP while limiting funding ratio downside risk to a fixed level. From an implementation standpoint, it has the advantage over the probability-maximising strategy that it is only based on observable parameters.

In order to achieve the highest success probability, the GBI strategy embeds a stop-gain mechanism, by which all assets are transferred to the GHP on the first date the aspirational goal is hit, that is if and when current wealth becomes sufficiently high to purchase the target level of replacement income cash flows. By using the proper GHP and a risk-controlled investment approach, retirement GBI strategies secure a fixed fraction of the purchasing power of each dollar invested without sacrificing upside potential.

External links

References

- ↑ Statman, Meir (2004-07-01). "The Diversification Puzzle". Financial Analysts Journal 60 (4): 44–53. doi:10.2469/faj.v60.n4.2636. ISSN 0015-198X.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Brunel, Jean L.P. (2015). Goals-Based Wealth Management. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-99590-7.

- ↑ Parker, Franklin J. (2021-01-02). "A Goals-Based Theory of Utility". Journal of Behavioral Finance 22 (1): 10–25. doi:10.1080/15427560.2020.1716359. ISSN 1542-7560. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427560.2020.1716359.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Shefrin, Hersh; Statman, Meir (2000). "Behavioral Portfolio Theory". The Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 35 (2): 127–151. doi:10.2307/2676187. ISSN 0022-1090.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Das, Sanjiv; Markowitz, Harry; Scheid, Jonathan; Statman, Meir (April 2010). "Portfolio Optimization with Mental Accounts" (in en). Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 45 (2): 311–334. doi:10.1017/S0022109010000141. ISSN 1756-6916.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Brunel, Jean L. P. (2006-07-31). "How Sub-Optimal—If at All—Is Goal-Based Asset Allocation?" (in en). The Journal of Wealth Management 9 (2): 19–34. doi:10.3905/jwm.2006.644216. ISSN 1534-7524. https://jwm.pm-research.com/content/9/2/19.

- ↑ Jeffrey, Robert H.; Arnott, Robert D. (1993-04-30). "Is Your Alpha Big Enough To Cover Its Taxes?" (in en). The Journal of Portfolio Management 19 (3): 15–25. doi:10.3905/jpm.1993.710867. ISSN 0095-4918. https://jpm.pm-research.com/content/19/3/15.

- ↑ Brunel, Jean L.P. (1997). "The Upside-Down World of Tax-Aware Investing". Trusts and Estates 136: 34–42.

- ↑ Pan, Carrie H.; Statman, Meir (2012-08-01) (in en). Questionnaires of Risk Tolerance, Regret, Overconfidence, and Other Investor Propensities. Rochester, NY.

- ↑ Deguest, R; Martellini, L; Milhau, V; Suri, A; Wang, H (March 2015). "Introducing a Comprehensive Investment Framework for Goals-Based Wealth Management.". EDHEC-Risk Institute Publication. https://risk.edhec.edu/publications/introducing-comprehensive-investment-framework-goals-based-wealth-management.

- ↑ Chhabra, A (2005). "Beyond Markowitz: A Comprehensive Wealth Allocation Framework for Individual Investors". Journal of Wealth Management 7 (4): 8–34. doi:10.3905/jwm.2005.470606.

- ↑ Giron, K; Martellini, L; Milhau, V; Milhau, J; Suri, A (May 2018). "Applying Goal-Based Investing Principles to the retirement Problem". EDHEC-Risk Institute Publication. https://risk.edhec.edu/publications/applying-goal-based-investing-principles-retirement-problem.

- ↑ Amenc, N; Malaise, P; Martellini, L (2004). "Revisiting Core-Satellite Investing – A Dynamic Model of Relative Risk Management". Journal of Portfolio Management 31 (1): 64–75. doi:10.3905/jpm.2004.443322.

|