Finance:History of business architecture

The history of business architecture has its origins in the 1980s. In the next decades business architecture has developed into a discipline of "cross-organizational design of the business as a whole"[1] closely related to enterprise architecture. The concept of business architecture has been proposed as a blueprint of the enterprise,[2][3] as a business strategy,[4] and also as the representation of a business design.[5] The concept of business architecture has evolved over the years. It was introduced in the 1980s as architectural domains and as an activity of business design. In the 2000s the study and concept development of business architecture accelerated. By the end of the 2000s the first handbooks on business architecture were published, separate frameworks for business architecture were being developed, separate views and models for business architecture were further under construction, the business architect as a profession evolved, and more businesses added business architecture to their agenda.

By 2015 business architecture has evolved into a common practice. The business architecture body of knowledge has been developed and is updated multiple times each year, and the interest from the academic world and from top management is growing.[citation needed]

Overview

Business architecture has its roots in traditional cross-organizational design. Bodine and Hilty (2009) stipulated, that the "responsibility for the cross-organizational design of the business as a whole, the work of the Business Architect, has historically fallen to the CEO or their assignee, supported by generalist management consulting firms whose teams of MBAs work with corporate managers to transform strategy into new business configurations using the newest tools."[1] John Zachman (2012) commented in this context, that "a lot of material has been written about business architecture (by some definition), going back to The Principles of Scientific Management (1911) by Frederick Taylor."[6]

One of the roots of business architecture lies in the proposals for enterprise architecture made since the 1980s and 1990s. Bernus & Noran (2010) distinguished two types of proposals. On the one hand "Proposals that created generally applicable ‘blueprints’ (later to be called reference models, partial models...) so that the activities involved in the creation (or the change) of the enterprise could refer to such a common model (or set of models)."[7] And on the other hand "proposals which claimed that to be able to organise the creation, and later the change, of enterprises one needs to understand the life cycle of the enterprise and of its parts... the ‘Enterprise Reference Architecture’."[7]

More specific about the emerge of business architecture Whelan & Meaden (2012) described, that this emerged against a backdrop of change. The business architecture is "maturing into a discipline in its own right, rising from the pool of inter-related practices that include business strategy, enterprise architecture, business portfolio planning and change management – to name but a few.[8]

1980s

Concept

The concept of business architecture emerged in the 1980s in the field of information systems development. One of the first to mention business architecture was the British management consultant Edwin E. Tozer in the 1986 article "Developing strategies for management information systems."[9] He introduced the concept of business architecture in the context of business information systems planning, and distinguished:

- Business architecture, and

- Information architecture,

And he explained, that "each entity class in the Information Architecture is represented in some database and each business function may be supported by one or more systems."[9] In this paper Tozer was "prescriptive about the order in which [strategy] issues should be identified.",[10] and focussed on "IS adaptability to organizational strategies."[11]

First models

The American organizational theorist William R. Synnott (1987) presented one of the first models of business architecture, (see image), in the context of data management. Synnott wanted to develop an overall Information Resource Management (IRM) architecture, and proposed business architecture as its foundation. He described:

Business architecture is the foundation upon which the IRM architecture rests. The architectural model consists of a set of building-blocks of linked architectures which together form the basis for the technology infrastructure of the firm... In the figure data architecture and communication architecture are shown as horizontal bars because these are corporate-wide information resource components. They serve all business units. The four vertical resource components are business specific. The resources can be divided according to the business units they serve. That us, data and communication might be centralizes resources, whereas human resources (professional systems staffs), computers, user-computing, and systems could all be decentralized resources to one degree or another.[12]

This model of Information Resource Management (IRM) distinguished seven types of architecture:

- Centralized: Business architecture, Data architecture, and Communication architecture

- Decentralized : Human resources architecture, Computer architecture, User-computing architecture, and Systems architecture.

This type of architectural model classifies different types of architecture. In the later theories and models different sets of architectures have been proposed. For example, the late 1980s NIST Enterprise Architecture Model distinguished five types, and this was incorporated in the 1990s Federal Enterprise Architecture, which contained four types of architecture.

Base for the total development process

Synnott (1987) furthermore described, how business architecture should work and introduced the idea of architectural planning:

The business architecture of the company (organization structure, strategic business units and missions, product and services) is the foundation of IRM planning. Since every company has an existing architecture, architectural planning begins with an inventory of the firm's information resources. Assembling the various information resource components' inventories results in an "as is" picture of the corporation's technology structure. From this inventory, the CIO can analyze the strengths and weaknesses of the company's information resources, particularly as they relate to business information needs as identified in the strategic planning process. From this analysis one can evolve an architectural plan, which is a "to be" picture of where one wants to go and how to get there, not just a picture of the status quo.[12]

Cees J. Schrama. (1988) of the European IFIP Technical Committee on Information Systems IFIP TC8 presented the opinion, that "business architecture is required to provide a solid base for the total development process." He pictured another model consisted of elements such as information processing architecture and network architecture, and explained:

[Business architecture] contains the fundamentals for the information processing architecture, where process data, support systems and network architecture are performed. In business architecture the following can 'be identified:

- - enterprise analysis: to indicate the business domains

- - business analysis

- - Information systems planning

There are some basic elements in business architecture: management, organization, processes to be performed and data to be made available/delivered. In the past, when mainly operational systems were developed, the processes received considerable attention. Information was seen as being needed to perform processes. This is changing. It is becoming important to have data available to serve information retrieval needs as well.[13]

These ideas around the concept of architectural planning evolved in the early 1990s into frameworks, such as TAFIM, the predecessor of TOGAF.

View models of enterprise architecture

In the 1987 article "A Framework for Information Systems Architecture" John Zachman presented some of the principles of Enterprise architecture,[14]

Framework for information systems architecture

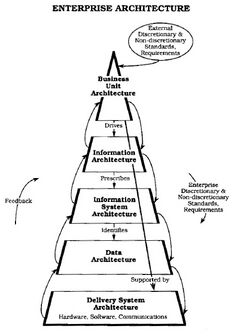

In the 5th NIST workshop on Information Management Directions (1989) a working groups under guidance of W. Bradford Rigdon developed one of the first Enterprise Architecture frameworks, the NIST Enterprise Architecture Model. In this model business architecture was incorporated as one of the layers of Enterprise Architecture. Bradford Rigdon et al. (1989) brought it like this:

A discussion of architecture must take into account different levels of architecture. These levels can be illustrated by a pyramid, with the business unit at the top and the delivery system at the base. An enterprise is composed of one or more Business Units that are responsible for a specific business area. The five levels of architecture are

- Business Unit

- Information

- Information System

- Data

- Delivery System

The levels are separate yet interrelated... The idea if an enterprise architecture reflects an awareness that the levels are logically connected and that a depiction at one level assumes or dictates that architectures at the higher level.[15]

In the original 1989 illustration of the NIST AE Framework (see image) the top layer was named "Business Unit Architecture." In representation of this model in the 1990s the top layer was named "Business architecture."

1990s

The unfolding information age

In the 1990s the information age was unfolding[16] changing the global market economy. With the businesses adapting, the new concept of business architecture was presented as promising alternative. Gharajedaghi (1999) explained the context:

In a global market economy with ever-increasing levels of disturbance, a viable business can no longer be locked into a single form or function. Success comes from a self-renewing capability to spontaneously create structures and functions that fit the moment. In this context, proper functioning of self-reference would certainly prevent the vacillations and the random search for new products/markets that have, over the past years, destroyed so many businesses.

In fact, the ability to continuously match the portfolio of internal competencies with the portfolio of emerging market opportunities is the foundation of the emerging concept of new business architecture...[17]

According to Bodine and Hilty (2009) "important advances in this area borrowed from the operations discipline came in 1993 in the form of Michael Hammer and James Champy‘s book Reengineering the Corporation, which introduced tools for mapping and optimizing business activities using process modeling. The Balanced Scorecard developed by Robert Kaplan and David Norton at about the same time enabled the business to measure overall corporate success against goals on qualitative as well as quantitative dimensions."[1]

Descriptions

In the 1990s works the concept of business architecture is presented in distinguished ways:

- As activity : Lindsay & Price (1991) for example presented business architecture as a "self security activity," which included the "study of a function, including its component organizations, tools, methods, and relationships, both internal and external... The very activity of identifying and listing all these elements is an important learning process for managers. In addition to the element identification and listing processes, the architecture develops a set of principles. Principles are semi-permanent statements of philosophy. That is, they are the basic rules by which managers agree they want to operate."[18]

- As blueprint or model of the enterprise : Bourke (1994) described it as "a set of integrated blueprints of the ... [enterprise]'s business processes,"[2] and Veasey (1994) spoke of business architecture as "a model of the enterprise which is a mechanism for the management of change."[19]

- As strategy for any change program : Davis (1996) for example described that business architecture can be used to "describe the type of comprehensive plan required to set the stage for integrated change programmes. The term "architecture" connotes the level of creativity and holistic change required to achieve process excellence. A comprehensive business architecture defines the way in which human performance, processes and technology will be integrated to transform business performance and create value."[4]

Business architectures is presented as tool for change management, acknowledged Van Rensburg (1997). It "provide organisations with the means to understand organisational activities in such a manner that it is used as a mechanism to support the organisation through the business transformation process. Using an object-oriented modelling approach in the design of the business architecture allows for a robust modelling approach which captures real world instances in a business architecture repository. This enables the creation and caption of organisational understanding required for the transformation process."[20]

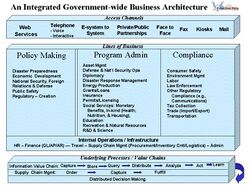

FEA and business subarchitecture

In 1996 the US government introduced the Clinger–Cohen Act, to improve the acquisition and management of their information resources.

Enterprise reference architecture

Beside the enterprise architecture frameworks a second type of architectural models were proposed in the late 1980s and early 1990s, which were called Enterprise Reference Architecture.[7]

- GRAI-GIM (Doumeingts, 1987)

- PERA (Williams 1994)

- CIMOSA (CIMOSA Association 1996),

- Architecture of Integrated Information Systems (Scheer 1999), and

- GERAM (IFIP-IFAC Task Force, 1999)

Foundation

In 1999 two works on business architecture and its foundation were published, which became two of the most cited works on business architecture. In his "Systems thinking: Managing chaos and complexity" Jamshid Gharajedaghi presented a set of principles to design business architecture, which were based on systems thinking. Gharajedaghi argued, that business Architecture should be considered a system:

Business Architecture is a general description of a system. It identifies its purpose, vital functions, active elements, and critical processes and defines the nature of the interaction among them. Business architecture consists of a set of distinct but interrelated platforms, creating a multidimensional modular system. Each platform represents a dimension of the system, signifying a unique mode of behavior with a predefined set of performance criteria and measures.[17]

The IBM researcher Douglas W. McDavid presented the paper "A standard for business architecture description." According to Evernden & Evernden (2003) this paper described a "high-level semantic framework of standard business concepts – abstracted from experience, enterprise business models, the organization of business terminology and the various generic industry reference models. There is an excellent discussion on what constitutes business architecture and the nature and use of information categories, although concepts such as product and agreement seem to be missing."[21] McDavid argued:

The concepts in the Business Architecture description provide a semantic framework for speaking about common business concerns... For our purposes, this semantic structure provides a common set of concept patterns to be able to understand the types of content that needs to be supported in technology-based information systems... a set of generic concepts and their interrelationships organize business information content in terms of requirements on the business, the boundary of the business, and the business as a system for delivery of value.[22]

2000s

NOTE: This Framework draws heavily from BusinessGenetics Business Modelling Language (BML)

Business architect

According to Bodine and Hilty (2009)

The arrival of Internet technologies like email, instant messaging and online data repositories in the mid-1990s opened up tremendous flexibilities in the ways co-workers could collaborate, while the new ability of buyers and sellers to interact in virtual space and transact online changed the traditional structure of businesses...

By the late 1990s, MBAs with advanced skills in Internet technologies began developing live business models for e-commerce websites in real-time. They used the development tools to both represent and build the business at the same time. The model became the business, and thousands were launched, allowing companies to access vast volumes of data and respond rapidly to changing market conditions... A Google search on ―Business Architect‖ at the time returned just 12 results... A Google search on ―Business Architect‖ in 2009 returns over 1 million listings.

This is just the beginning of a valuable and rapidly expanding profession. Today‘s Business Architects take a holistic view of the complete business representing all interests and engaging all expertise. They see the business organization as a constantly changing, dynamic organism that balances central planning with individual initiative to achieve its mission through the articulate implementation of its corporate strategy.[1]

Tools and frameworks

According to Bodine and Hilty (2009)

Important advances in this area borrowed from the operations discipline came in 1993 in the form of Michael Hammer and James Champy‘s book Reengineering the Corporation, which introduced tools for mapping and optimizing business activities using process modeling. The Balanced Scorecard developed by Robert Kaplan and David Norton at about the same time enabled the business to measure overall corporate success against goals on qualitative as well as quantitative dimensions.[1]

According to Bernus & Noran (2010):

Architecture Frameworks have been used in many industries, including the domains of industrial automation / manufacturing / production management, business information systems (of various kinds), telecommunications and defence. Part of the Enterprise Architecture practice is ‘enterprise engineering’ and the practice of ‘enterprise modelling’ (or just modelling) and complete AFs describe the scope of modelling (which later can be summaised as a Modelling Framework that is part of the AF).[7]

One specific type of Framework is called the "Enterprise Reference Architecture." According to Bernus & Noran (2010):

Several proposals emerged in those two decades – e.g. PERA (Williams 1994), CIMOSA (CIMOSA Association 1996), ARIS (Scheer 1999), GRAI-GIM (Doumeingts, 1987), and the IFIP-IFAC Task Force, based on a thorough review of these as well as their proposed generalisation (Bernus and Nemes, 1994) developed GERAM (IFIP-IFAC Task Force, 1999) which then became the basis of ISO15704:2000 “Industrial automation systems – Requirements for enterprise-reference architectures and methodologies”...[7]

Business Architecture Working Group

The Business Architecture Special Interest Group (BASIG) is a working group on business architecture of the Object Management Group (OMG). This working group was founded in 2007 as the Business Architecture Working Group (BAWG).

Business strategy

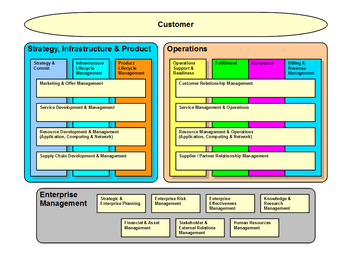

In the 2006 article "Business Architecture: A new paradigm to relate business strategy to ICT," Versteeg & Bouwman explained the relation between business architecture, business activities and business strategy.[23] They wrote:

We use the concept of 'Business Architecture’ to structure the responsibility over business activities prior to any further effort to structure individual aspects (processes, data, functions, organization, etc.). The business architecture arranges the responsibilities around the most important business activities (for instance production, distribution, marketing, et cetera) and/or economic activities (for instance manufacturing, assembly, transport, wholesale, et cetera) into domains [24]

Versteeg & Bouwman also stipulated, that "the perspectives for subsequent design next to organization are more common: information architecture, technical architecture, process architecture. The various parts (functions, concepts and processes) of the business architecture act as a compulsory starting point for the different subsequent architectures. It pre-structures other architectures. Business architecture models shed light on the scantly elaborated relationships between business strategy and business design. We will illustrate the value of business architecture in a case study."[25]

2010s

Handbooks

In the 2010 the first handbooks on Business architecture were published. In the US William M. Ulrich and Neal McWhorter of the OMG Business Architecture Special Interest Group published the "Business Architecture: The Art and Practice of Business Transformation," in 2010.

In 2012 in Britain the business consultants Jonathan Whelan and Graham Meaden published their "Business Architecture: A Practical Guide."[26]

Definition

In several sources in the exact definition of "business architecture" is under review. In 2008 Jeff Scott had commented in this matter:

Interest in business architecture is growing dramatically. During the past two years both IT and business leaders have joined the discussion about the need for a well-defined business architecture. Though there is a great deal of discussion, there is little consensus about what business architecture is, how it should be pursued, and what value it delivers. Business architects in IT as well as in the business have started developing business-unit-wide and enterprise-wide business architectures, learning as they go. Their ultimate goals are to improve business decision-making and facilitate better alignment between IT and the business units it supports. Architecture teams that want to play a leading role in business architecture development must start soon or be left behind.[27]

Other sources came to the same conclusion, that over the years many different definitions of business architecture have been proposed[26][28][29][30] Some of the more notable definitions have described business architecture as:

- "A blueprint of the enterprise that provides a common understanding of the organization and is used to align strategic objectives and tactical demands" - OMG Business Architecture Working Group, 2008[3]

- "The business strategy, governance, organization, and key business processes information, as well as the interaction between these concepts." - TOGAF, 2009[31]

- "The formal representation and active management of business design." - SOA Consortium, EA2010 Working group on Business Architecture, 2010[5]

The discussion kept going. John Zachman (2012) declared in this matter, that "a lot of people define business architecture differently (I know a lot of people who have a lot of different opinions and definitions for business architecture). Not too many people do business architecture, at least not in a comprehensive and definitive fashion (in my estimation)..."[6]

Roots in various academic domains

Ideas and definitions about business architecture originate from different academic sub disciplines, where the concept of business architecture and methods and techniques are developing in numerous initiatives. A selection of related subfields:[citation needed]

- Organizational theory inspired by systems thinking, cybernetics, complexity science, etc.

- Systems analysis and design, system engineering, business engineering, business modeling, business process modeling, business process management, business process reengineering[1] etc.

- Software engineering, information engineering, information technology management, etc.

- Enterprise architecture, enterprise engineering,[7] enterprise modeling,[7] enterprise ontology, enterprise resource planning, etc.

Field of practice

Guitarte (2013) stipulated, that also different types of organizations have been active, and created a so-called "business architecture vortex.” He listed four types:

- Influencers: Academe, Various authors, Cutter, Forrester, Media, Gartner, IIR

- Third-party vendors: Metastorm, IBM, Sparx, Troux, Mega, BrainstormCentral, Pega, BAI, BPMI, Progress

- Communities of practice: Business Architecture Guild, Business Architecture Society, BAA, BizArchCommunity, BAA, IIBA, PMI, AOGEA

- Standards-setting bodies: ISO, BPMN, OMG, MDA, BASIG, The Open Group, TOGAF, BPM/SOA, BEI[32]

Guitarte commented, that "influencers led followed by communities of practice and standards-setting bodies; vendors followed. Conflicting ideas provide opportunity to define the future of business architecture profession."[32]

Management interests

Surveys have reported a growing interest of management in business architecture, as well as on universities:

- In 2004 Jaap Schekkerman already suggested that "Enterprise Architecture was ranked near the top of the list of most important issues considered by CEO’s and CIO’s."[33]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Paul Arthur Bodine and Jack Hilty. "Business Architecture: An Emerging Profession," at businessarchitectsassociation.org, Business Architects Association Institute. April 28, 2009. (online )

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Michael K. Bourke (1994). Strategy and architecture of health care information systems. p. 55

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 OMG Business Architecture Working Group. "Business Architecture Working Group," at bawg.omg.org, Oct 10, 2008. (archive.org, Oct. 10, 2008).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Peter T. Davis (1996) Securing Client/server Computer Networks. p. 324

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 SOA Consortium, EA2010 working group. Business Architecture; The Missing Link between Business Strategy and Enterprise Architecture . Copyright by OMG, 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 John A. Zachman "Foreword" in: Jonathan Whelan, Graham Meaden (2012) Business Architecture: A Practical Guide. p. xv

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Bernus, Peter, and Ovidiu Noran. "A metamodel for enterprise architecture," Enterprise Architecture, Integration and Interoperability. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2010. 56-65.

- ↑ Jonathan Whelan, Graham Meaden (2012) Business Architecture: A Practical Guide. p. 2

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Tozer, Edwin E. "Developing strategies for management information systems." Long Range Planning 19.4 (1986): 31-40.

- ↑ Bennett, Jane, and Pam Hinton. "Case study-an information systems strategy: development and evolution at the University of Hertfordshire." (1995).

- ↑ Palanisamy, Ramaraj. "Measurement and Enablement of Information Systems for Organizational Flexibility: An Empirical Study." Journal of Services Research 3.2 (2003).

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 William R. Synnott (1987). The Information Weapon: Winning Customers and Markets With Technology. p. 199-220

- ↑ Cees J. Schrama. "Composition and Decomposition in the Development of IS," in: Péter Kovács & Elek Straub (editors). Governmental and Municipal Information Systems: Proceedings of the IFIP TC8 Conference on Governmental and Municipal Information Systems, Budapest, Hungary, September 8–11, 1987. IFIP TC8, 1988. p. 161

- ↑ Zachman, John A. "A framework for information systems architecture." IBM systems journal 26.3 (1987): 276-292.

- ↑ W. Bradford Rigdon (1989) "Architectures and Standards". In: Information Management Directions: The Integration Challenge E.N. Fong and A.H. Goldfine (eds). NIST Sept 1989. p. 137; Partly cited in: IT Governance Institute (2005) Governance of the Extended Enterprise. p. 89.

- ↑ Zachman, John A. "Enterprise architecture: The issue of the century." Database Programming and Design 10.3 (1997): 44-53.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Gharajedaghi, Jamshid. Systems thinking: Managing chaos and complexity: A platform for designing business architecture. Elsevier, 1999; 2nd ed. 2005, p. 152

- ↑ David T. Lindsay, W. L. Price, Information security: proceedings of the IFIP TC11 Seventh International Conference on Information Security--Creating Confidence in Information Processing, IFIP/Sec '91, Brighton, UK, 15–17 May 1991. 1991, p. 81.

- ↑ Veasey, Philip W. "Managing a programme of business re-engineering projects in a diversified business." Long Range Planning 27.5 (1994): 124-135.

- ↑ Van Rensburg, A. C. J. "An object-oriented architecture for business transformation." Computers & industrial engineering 33.1 (1997): 167-170.

- ↑ Roger Evernden, Elaine Evernden (2003). Information First: Integrating Knowledge and Information. p. 200

- ↑ McDavid, Douglas W. "A standard for business architecture description." IBM Systems Journal 38.1 (1999): 12-31.; As cited in: Glissman & Sanz (2009, p. 3).

- ↑ Schelp, Joachim, and Robert Winter. "Language communities in enterprise architecture research." Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Design Science Research in Information Systems and Technology. ACM, 2009.

- ↑ Versteeg, Gerrit & Bouwman (2006, p. 92), as cited in: McClure, Mark. Framing a Collaborative Enterprise Architecture Governance Program within the Context of Service-Oriented Software Systems Development. University of Oregon Applied Information Management Program, March 2007.

- ↑ Versteeg, G & H. Bouwman. "Business Architecture: A new paradigm to relate business strategy to ICT." Information Systems Frontiers 8 (2006) pp. 91-102.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Meaden & Whelan 2012

- ↑ Jeff Scott (2008), Business Architecture’s Time Has Come, Forrester Publication. (summary at forrester.com)

- ↑ Whittle & Myrick (2004)

- ↑ Kerrie Holley, Ali Arsanjani. 100 SOA Questions: Asked and Answered, 2010.

- ↑ Nick Malik, "Many (flawed) Definitions of Business Architecture," blogs.msdn.com, 11 Sept. 2012.

- ↑ The Open Group. TOGAF™ Version 9 Foundation Study Guide, 2009, p. 45

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Andrew Guitarte, "Business Architecture Trends & Methods." (2013).

- ↑ Jaap Schekkerman, How to Survive in the Jungle of Enterprise Architecture Frameworks: Creating Or Choosing an Enterprise Architecture Framework, 2004. p. 19

Further reading

- Gharajedaghi, Jamshid. Systems thinking: Managing chaos and complexity: A platform for designing business architecture. Elsevier, 1999; 2nd ed. 2005; 3rd ed. 2011

- Susanne Glissman, and Jorge Sanz. "A comparative review of business architecture." IBM Research Report,2009.

- William M. Ulrich, Neal McWhorter, Business Architecture: The Art and Practice of Business Transformation, Meghan-Kiffer Press, 2010;

- Jonathan Whelan, Graham Meaden. Business Architecture: A Practical Guide. 2012.

- Ralph Whittle, Conrad B. Myrick. Enterprise Business Architecture: The Formal Link between Strategy and Results, 2004

External links

|