Finance:Mr Keynes and the Classics

John Hicks’s 1937 paper “Mr. Keynes and the ‘classics’: a suggested interpretation” is the most influential study of the views presented by J. M. Keynes in his General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money of February 1936. It gives “a potted version of the central argument of the General Theory ” [1] as an equilibrium specified by two equations (shown as intersecting curves in the IS-LM diagram) which dominated Keynesian teaching until Axel Leijonhufvud published a critique in 1968. Leijonhufvud’s view that Hicks misrepresented Keynes’s theory by reducing it to a static system was in turn rejected by many economists who considered much of the General Theory to be as static as Hicks portrayed it. James Tobin described the IS-LM model as:

... the tool of first resort. If you are faced with a problem of interpretation of the economy – policy or events – probably the first thing you can do is to try to see how to look at it in these [IS-LM] terms.[2]

Background

Publication history

'Mr Keynes and the Classics’ was first published in Econometrica (April 1937) and reprinted in ‘Critical essays in monetary theory’ (1967) and again in ‘Money, interest and wages’ (1982), this time with a prefatory note.

Several of Hicks’s other papers deal with the same subject. His review of the General Theory was published in the Economic journal in June 1936 and reissued in ‘Money, interest and wages’. ‘The classics again’ was published in the same journal in 1957 and reissued in ‘Critical essays in monetary theory’. ‘IS-LM – an explanation’ was published in the winter 1980-1 issue of the Journal of post Keynesian economics and reprinted in ‘Money, interest and wages’.

Origins of ‘Mr Keynes and the Classics’

Hicks’s paper as first was based on a version read at a meeting of the Econometric Society at Oxford in September 1936, and taking account of the discussion which took place there and later at Cambridge.

According to Warren Young it should be ‘regarded not so much as an original and new piece of analysis but as a synthesis of earlier interpretational attempts by [Roy] Harrod and [James] Meade’.[3] Meade and Harrod ‘themselves were intimately associated with the development of the General Theory ’;[4] Harrod was one of the colleagues to whom Keynes sent proofs of the book for comment.[5] Gonçalo L. Fonseca specifically mentions that “The equations of the IS-LM model were written down by Harrod (1937), but the (later) drawing of the diagram by Hicks robbed him of his claims to precedence”.[6]

Hicks’s own account of the origins of the paper is rather different.[7] He had been working independently on questions overlapping those addressed by the General Theory and found much in it which corresponded to his own thinking. It is this convergence of thinking, rather than the prior knowledge supplied by others, which accounts for his rapidly arriving at a clear picture of Keynes’s views. This account explains the singlemindedness of Hicks’s interpretation, which homes in on Book IV of the General Theory and on excessive wages as a cause of unemployment, while other reviewers were struggling to reconcile the different elements of Keynes’s thought.

Hicks’s relatively classical interpretation of Keynes made him the target of criticisms from more radical Keynesians. He had considered the General Theory a more conservative work than Keynes’s earlier Treatise on Money and given it a favourable review. But he came to have doubts about the formalism he’d presented in ‘Mr Keynes and the Classics’ and oscillated between retractions and reavowals.

Terminology

The two curves in Hicks’s original diagram are labelled IS and LL, and his original name for the model was IS-LL (or possibly even SI-LL), but the name which stuck was IS-LM. It is also known as the ‘Hicks-Hansen model’, reflecting the importance of Alvin Hansen’s 1953 ‘Guide to Keynes’ (which interpreted Keynes’s system along the lines of Hicks’s model) in introducing Keynesian ideas to America.

Mathematical representation of Keynes’s theory

The General Theory

See the article on the General Theory for a description of Keynes’s economic ideas. Chapters 1–13 and 15 develop the concepts on which Keynes’s model is based. The model itself is receives an initial statement in Chapter 14 and is ‘restated’ in Chapter 18: [8] it is these statements which Hicks presented in the mathematical form of an equilibrium specified by simultaneous equations.

The choice of units

In §I Hicks presents Keynes’s theories in opposition to Pigou’s 1933 “Theory of Unemployment”. He remarks that:

Professor Pigou’s theory runs, to a quite amazing extent, in real terms... The ordinary classical economist has no part in this tour de force.

But if, on behalf of the ordinary classical economist, we declare that we would have preferred to investigate many of those problems in money terms, Mr. Keynes will reply that there is no classical theory of money wages and unemployment.

This attaches considerable importance to the choice of units, as Keynes himself did when criticising Pigou. The explanation is that the conversion factors – the price level and the wage rate – are not neutral like physical units, but themselves part of the analysis.

In fact Hicks’s use of units was inconsistent, as was Keynes’s. In this account we make no attempt at precision, referring the reader to the article on wage units for necessary corrections, but reminding him or her that when Hicks or Keynes claims that two equations can be solved without reference to the ‘first postulate’, there is reason to suppose that they have failed to notice the need for a conversion factor which brings in an additional unknown.

Keynes had avoided real values because their use requires the postulation of a single ‘representative’ price level. At times in the General Theory he allowed every industry to have its own price and elasticity of employment.[9] Hicks split the economy into just two sectors: capital goods and consumption goods. Even this is more than he needed, and in the account below we treat the economy as a single sector.

Hicks assumes that the wage rate is fixed externally (‘exogenous’).

The variables of the system

The paragraph in which Hicks sets out his variables is the main point of obscurity in an otherwise readable paper. His variable names are poorly chosen and inconsistent with those used by Keynes which we adopt below.

- W is the wage rate in money terms. [Hicks writes w.]

- The total output is equal to total income Y, which is the sum of saving and consumption or of investment and consumption, i.e. Y = I + C or Y = S + C. [Hicks divides output into investment goods x and consumption goods y, and expresses income I as Ix + Iy.]

- The number of workers employed is N. [Hicks splits it into Nx and Ny.]

- Output is a function of the number of workers and can be written Y (N ). [Hicks writes x = fx(Nx) and y = fy(Ny).]

- M is the externally determined money supply.

- r is the interest rate. [Hicks denotes it by i.]

- We let P be the price level, i.e. the money price of a unit of real output. Hicks does not give it a symbol.

Some immediate consequences can be drawn. The ‘first postulate of classical economics’ asserts that the wage is equal to the marginal product,[10] so we might write:

- Y' (N ) = W / P

Unfortunately this isn’t quite correct, since it is necessary to differentiate real output and multiply the result by P rather than differentiating output in money terms. Hicks avoids this difficulty by giving the equation a strange form, differentiating an independent with respect to a dependent variable [Px = w (dNx / dx )]. He then gives a further equation [written I = wx (dNx / dx ) + wy (dNy / dy )] in which the price levels by sector determine the relation between output and income; but if we avoid representing income and output by different symbols we can dispense with this equation.

He remarks (in our notation) that since Y is a (monotonic) function of N, once it is given N is given; but, working in money units, he should have added that P needs also to be given.

The ‘classical’ theory

Hicks starts with the quantity theory of money:

- M = Y / V

where V is the velocity of money. [He himself writes M = k I (where k =1/V ). ‘k ’ is Keynes’s symbol for the multiplier.]

His second equation can be written:

- Is (r ) = S (Y ,r )

where Is (r ) is ‘the amount of investment (looked at as the demand for capital)’ which is ‘what becomes of the marginal-efficiency-of-capital schedule in Mr. Keynes’s work’. S (Y ,r ) is the propensity to save (expressed as a function of money income). He comments (rather misleadingly) that the presence of Y as an argument to S is unnecessary given that it is by now determined by the quantity theory.

[This equation is expanded into two due to Hicks’s proliferation of symbols. One equation in words is ‘Investment = Saving’: in symbols the two equations are Ix = C (i ) and Ix = S (i,I ). ‘C ’ stands for ‘capital’ whereas for Keynes it stood for ‘consumption’. So Hicks’s C (i ) is our Is (r ) while his S (i,I ) is our S (Y ,r ).]

The two equations as we have given them can be solved together for Y and r ; and total employment is considered as determined by income Y.

Hicks sums up:

I think it will be agreed that we have here a quite reasonably consistent theory, and a theory which is also consistent with the pronouncements of a recognizable group of economists... Historically this theory descends from Ricardo... it is probably more or less the theory that was held by Marshall...

This is historically inaccurate; see below.

In fact both of the equations Hicks takes from Keynes are part of the classical analysis. The quantity theory has precisely the sense Hicks gave to it. In classical theory the equation Is (r ) = S (Y ,r ) is the equilibrium condition of the loans market and determines the rate of interest rather than the level of employment. (See Keynes’s Chapter 14.) Working in real terms, it is unlikely that any classical economist would have seen Hicks’s two equations as comprising a complete set (see the General Theory ).

Mr Keynes’s ‘special’ theory

Hicks moves on to discuss industrial fluctuations in his §II, remarking that changes in the velocity of circulation can be related to changes in confidence, and asking whether velocity has not ‘abdicated its status as an independent variable’ [strictly he refers to his uninterpreted variable k, which can be recognised as the reciprocal of velocity in classical theory]. He adds that ‘this last consideration is powerfully supported by another’ since ‘on grounds of pure value theory, it is evident that the direct sacrifice made by a person who holds a stock of money is a sacrifice of interest’.

He now quotes Lavington (who also said that “It’s all in Marshall, if one only digs deeply enough” [11] ) as arguing that an individual will hold money up to the point at which the convenience of doing so is equal to the rate of interest.

The demand for money depends on the rate of interest! The stage is set for Mr. Keynes.

He contrasts the equations of ‘classical’ theory:

- M = Y / V Is (r ) = S (Y ,r )

with those adopted by Keynes:

- M = L(r ) Is (r ) = S (Y )

These differ from the classical equations in two ways. On the one hand, the demand for money is conceived as depending upon the rate of interest (Liquidity Preference)...

and more suprisingly, as depending solely on the rate of interest, with no possible influence from the level of income. And:

On the other hand, any possible influence of the rate of interest on the amount saved out of a given income is neglected... this second amendment is a mere simplification, and ultimately insignificant.

The liquidity preference doctrine is that of Keynes’s Chapter 13, rapidly superseded by his more comprehensive doctrine of Chapter 15. Its role in Keynes’s theory is unclear. It provides no mechanism for ensuring equilibrium between supply and demand of loans, but Hicks argued elsewhere that this equilibrium would be ensured anyway by Walras’s law.[12]

Mr Keynes’s ‘general’ theory

Hicks revises the equations to take account of the Chapter 15 theory of liquidity preference:

- M = L(Y,r ) Is (r ) = S (Y )

‘With this revision, Mr Keynes takes a big step back to Marshallian orthodoxy.’ In fact Keynes considers liquidity preference to be the sum of two functions so that it may be written:

- L(Y,r ) = L1(Y ) + L2(r )

Here L1 is the sum of transactions and precautionary demands and L2 is speculative demand. The form L(Y,r ) is slightly more generic than Keynes’s L1(Y ) + L2(r ) but the difference is purely notational.

The IS-LM model

Having analysed Keynes’s equilibrium system as a pair of simultaneous equations, Hicks then represents it graphically as two intersecting curves. The IS curve joins all the pairs (Y,r ) which satisfy the IS equation Is (r ) = S (Y ) and the LM curve joins the pairs which satisfy the LM equation L(Y ,r ) = M. The point of intersection of the two curves tells us the income Ŷ and the rate of interest r̂.

Under Keynes’s Chapter 13 liquidity preference doctrine the LM curve will be a horizontal line. Under his Chapter 15 doctrine, if L is an increasing function of Y and a decreasing function of r, then the LM curve will slope upwards. The IS curve always slopes downwards.

Source of the equations

In Chapter 14 Keynes identified the equation Is (r ) = S (Y ) as the main determinant of employment once its dependence on r has been eliminated through the liquidity preference function.

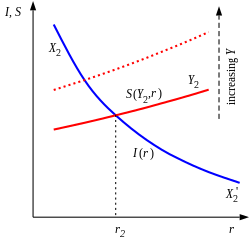

The discussion is presented in connection with a complicated diagram whose essential components are shown on the right. The vertical axis is saving/investment and the horizontal axis is the rate of interest. For a few representative levels of income he draws a curve showing the amount of saving which will take place for each level of income. One of these is shown as a solid red line; another, corresponding to a higher level of income, is shown as a dotted line. Both curves are increasing functions of r, which may be no more than a concession to the classical theory which Keynes is criticising by opposing it to his own. He himself viewed saving as independent of r, which would lead to functions plotted as horizontal red lines, but the analysis would be the same.

The saving curves are crossed by another set, each of which represents a different schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital. (In Chapter 14 he usually refers to the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital as the ‘investment demand-schedule’.) A single such curve X2X2' is drawn in blue on the right.

He begins the discussion by considering a given rate of interest r 1, and then postulates that ‘the investment demand-schedule shifts from X1X1' to X2X2'. He says that we are in the position of ‘not knowing the appropriate Y -curve’ and proceeds to give the following analysis:

If, however, we introduce the state of liquidity-preference and the quantity of money and these between them tell us that the rate of interest is r 2, then the whole position becomes determinate. For the Y -curve which intersects X2X2' at a position vertically above r 2 [i.e. the curve for that Y which satisfies Is (r 2) = S (Y,r 2)], will be the appropriate curve...

and he concludes that:

The X -curve and the Y -curves tell us... what income will be, if from some other source we can say what the rate of interest is.

This points us back to Chapter 13 where Keynes has written that...

... the quantity of money is the other factor, which, in conjunction with liquidity-preference, determines the actual rate of interest... if r is the rate of interest, M the quantity of money and L the function of liquidity-preference, we have M = L(r ).[13]

The Chapter 15 theory of liquidity preference

In Chapter 15 Keynes offers a new model of liquidity preference. He writes M1 and M2 as the amounts of money held in the first case for the transactions and precautionary motives combined, in the second for the speculative motive, and writes L1 and L2 as the associated demands. He then writes (on p199)

- M = M1 + M2 = L1(Y ) + L2(r )

This is the source of Hicks’s M = L(Y,r ). It follows that ‘the quantity of money... in conjunction with liquidity-preference’ can no longer determine the ‘actual rate of interest’ on their own and that the statement of Keynes’s theory in Chapter 14 needs to be modified.

It is not hard to see how to do this. Liquidity preference imposes a relationship between the interest rate and income for a given quantity of money, and this can be combined with the equation Is (r ) = S (Y ) exactly as was done by Hicks. It is not a step which Keynes himself took. In his Chapter 18 ‘restatement’ he recapitulates the account he has already presented in Chapter 14, but remarking in addition that a change in employment is liable ‘to raise (or lower) the schedule of liquidity-preference’ and that ‘the position of equilibrium will be influenced by these repercussions’.[14] Hicks did the best he could to make something coherent of this: when ‘Mr Keynes and the Classics’ was published, Keynes gave its ‘IS-LL equilibrium model’ his ‘largely unqualified acceptance’.[15]

Properties of the IS-LM model

Flatness of the LM curve

Under Keynes’s Chapter 13 liquidity preference doctrine the LM curve will be a horizontal line. Speaking more generally of the LM curve, Hicks says in §III that:

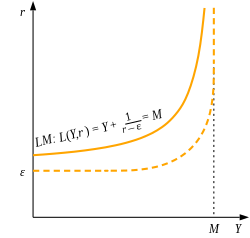

It will probably tend to be nearly horizontal on the left, and nearly vertical on the right. This is because there is (1) some minimum below which the rate of interest is unlikely to go, and (though Mr Keynes does not stress this) there is (2) a maximum to the level of income which can possibly be financed with a given level of money.

This argument needs to be considered with care, especially since the expression ‘on the left’ might be understood as meaning either for Y = –∞ or for Y = 0.

The full orange line in the graph shows an LM curve satisfying Keynes’s and Hicks’s postulates. It corresponds to the liquidity preference function

- L(Y,r ) = Y + 1 / (r –ε)

and is a standard rectangular hyperbola. The ‘maximum to the level of income which can possibly be financed with the given level of money’ is M itself, and the ‘minimum below which the rate of interest is unlikely to go’ might be taken as either ε or ε+1/M according to preference, and ε can be taken as positive, negative, or zero to accommodate different views of this minimum. As r approaches ε from above the speculative demand for money becomes infinite, and r can decrease no further.

Hicks draws an LM function similar to the dashed line in the figure, exaggerating the possible flatness of the curve.

It is easy to show that a perfectly flat LM curve cannot arise from Keynes’s Chapter 15 L(Y ,r ) function unless L1(Y ) is completely inelastic, in which case the Chapter 15 model degenerates to that of Chapter 13. The gradient of the LM curve is –L1'(Y ) / L2'(r ). For this to be zero we need either L1'(Y ) = 0 (i.e. perfectly inelastic L1) or L2'(r ) = –∞. The second condition can only realistically arise if L2 is itself infinite, in which case L1, and therefore Y, must be –∞.

Effect of the inducement to invest on the rate of interest

Hicks claims to have found in Keynes an assertion about ‘an increase in the inducement to invest not raising the rate of interest’. Unfortunately he doesn’t say where this occurs and it is doubtful that Keynes ever made it so categorically. Boianovsky proposes two candidate locations.[16] One of them is the first page of Chapter 13, but it is difficult to see anything there which supports Hicks’s contention. The second is from near the end of Chapter 14, where Keynes says that:

... when investment changes, income must necessarily change in just that degree which is necessary to make the change in saving equal to the change in investment... the practical advice of economists has... assumed, in effect, that, cet. par., a decrease in spending will tend to lower the rate of interest and an increase in investment to raise it. But if what these two quantities determine is, not the rate of interest, but the aggregate volume of employment, then our outlook on the mechanism of the economic system will be profoundly changed.

This is not as clear-cut as Hicks’s summary, but we may let it pass. It still leaves open the question of whether this remark is really part of Keynes’s system. Coming as it does at the end of Chapter 14, it reflects the liquidity preference doctrine of Chapter 13 and takes no account of its being superseded by a more general (and incompatible) doctrine in Chapter 15.

Hicks justifies the view he has attributed to Keynes from the supposed possibility that the LM curve will be horizontal. If the downward-sloping Is (r ) curve shifts upwards in the region of r̂, then its intercept with the LM curve will normally move upwards and to the right, but if the LM curve is horizontal in the region of interest then the intercept will move purely rightwards. On these grounds Hicks concludes that when we are on the horizontal part of the LM curve:

A rise in the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital only increases employment, and does not raise the rate of interest at all.

The liquidity trap

Hicks attaches importance to the existence of a lower limit on the interest rate and devotes a brief discussion to it. He points out that if the interest rate were negative then there would be no motive to lend, which introduces an initial lower bound, and adds that if the rate is very low, then there is more scope for it to increase than to decrease, with the result that people will hold onto money in the anticipation of rates increasing; and this phenomenon raises the effective lower limit.

He then asserts that the effect of an increase in the money supply is to shift the LM curve to the right, and this is true. To be precise, if the money supply is increased by ΔM then the curve will be shifted to the right at any point (Y,r ) by an amount equal to ΔM / L1'(Y ). If we assume that L1(Y ) is proportional to Y, this amounts to a constant shift.

He concludes that if the intercept with the IS curve is on the presumed horizontal section of the LM curve, then ‘merely monetary means will not force down the rate of interest any further’. He regards this possibility as distinguishing Keynes’s economic theories from those of the classics, and as characterising them as ‘the economics of depression’.

In later economic circumstances the risk of speculators having an unsatisfiable demand for money disappeared. Hicks then wrote that ‘in the inflationary conditions to which we have now become accustomed, it [the liquidity trap] is irrelevant’.[17] But later still, deflation reappeared in Japan and economists such as Paul Krugman found the liquidity trap to have regained its practical significance.[18]

Hicks’s generalisations of Keynes’s theory

In §IV Hicks remarks that ‘With the apparatus at our disposal, we are no longer obliged to make certain simplifications which Mr Keynes makes in his exposition’. He proposes to now write the saving function in a form equivalent to S (Y,r ), thus allowing for ‘any possible influence of the rate of interest upons saving’. Keynes did not deny such an influence, merely considering it ‘secondary and relatively unimportant’.[19]

And...

... what is more important, we can call in question the sole dependence of investment upon the rate of interest, which looks rather suspicious in the second equation [sc. Is (r ) = S (Y )]. Mathematical elegance would suggest that we ought to have I and i [i.e. Y and r ] in all three equations.

It is indeed more than suspicious that a demand function should be independent of income, but Hicks misdirects his suspicions. He goes on to remark that if current income is greater than that for which existing capital was planned, then ‘an increase in the demand for consumers’ goods’ will increase the expected return from new investment, at any rate if the heightened income is not considered as merely transient. He was right to think so, but Keynes was also right when he replied that the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital was already defined in terms of the expected return from new investment, and therefore took this effect into account without needing the extra parameter.[20]

Hicks later recognised that it was ‘quite un-Keynesian’ to add income as a parameter to Is (): ‘The introduction was so tempting mathematically; but the temptation would have been better avoided’.[21]

His third suggested generalisation is to incorporate adjustment of the money supply:

Instead of assuming, as before, that the supply of money is given, we can assume that there is a given monetary system... monetary authorities will prefer to create new money rather than allow interest rates to rise... Any change in liquidity preference or monetary policy will shift the LL [i.e. LM ] curve...[22]

Presumably we should write M (r ) in place of M. A similar dependence was proposed around the same time by Pigou. In Ambrosi’s words:

According to Pigou the quantity of money is not given. It is a function of the rate of interest.[23]

Ambrosi either missed Hicks’s reference to not assuming the money supply given or interpreted it differently since he wrote that:

Hicks failed to incorporate into the IS-LM scheme [Nicholas] Kaldor’s cherished idea of the ‘endogeneity of the quantity of money’.[24]

Modigliani’s extension of Hicks’s system

The influence of Hicks’s paper on subsequent work was partly through the extension of his model in Franco Modigliani’s ‘Liquidity preference and the theory of interest and money’.[25]

Modigliani takes Hicks’s equations (including the ‘first postulate’ which Keynes and Hicks had left to one side), expressing quantities in money terms (and therefore, like Hicks, assuming that the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital determines the amount of investment in money terms whose return will be greater than r – see wage unit). He concluded that ‘except in a limiting case’ it was ‘rigid wages’ which accounted for Keynesian unemployment. The limiting case was that of the liquidity trap.

Henry Hazlitt commented:

W. H. Hutt... has written: “Modigliani (whose 1944 article quietly caused more harm to the Keynesian thesis than any other single contribution) seems, almost unintentionally, to reduce to the absurd the notion of the coexistence of idle resources and price flexibility.” Modigliani’s article... seems to have particularly impressed the Keynesians because, beginning with the Keynesian vocabulary and many of the Keynesian concepts, he made alternative assumptions that led to some quite un-Keynesian conclusions.[26]

Modigliani’s conclusions were perfectly Hicksian, while Hicks was faithful to some of Keynes’s words which in turn were unfaithful to others; and what counts as ‘Keynesian’ is for everyone to decide for themselves.

Hicks’s interpretation of the General Theory

The formalism presented by Hicks is one in which unemployment is the consequence of artificially high wages rates. After sketching the IS-LM model in ‘The classics again’ he remarked that...

... the only way in which it [the construction so far reached] differs from what was taught by ‘classical’ economists... is in the assumption it makes about the behaviour of wages – that they can flex upwards but not downwards; but this is a special assumption that can be incorporated into any theory.[27]

On the other hand the concepts of aggregate, or effective, demand are nowhere mentioned in ‘Mr Keynes and the classics’ (nor in Hicks’s review of the General Theory, or in ‘The classics again’, and only sketchily in ‘IS-LM – an explanation’).

Keynes’s own view is slightly enigmatic. In the years preceding the General Theory he had certainly attributed unemployment to excessive wage rates, without necessarily seeing wage cuts as a remedy. The account he developed in Books IV and V of the General Theory has the fairly clear (though not undisputed) implication that wage rates are indeed responsible for unemployment, but this is not an inference he drew himself and is not his own interpretation of his theory. His own interpretation blames unemployment on a shortfall in aggregate demand which wage bargainers are powerless to change.

The interpretation is set out in Chapter 3 where Keynes writes that:

Malthus, indeed, had vehemently opposed Ricardo’s doctrine that it was impossible for effective demand to be deficient; but vainly... The great puzzle of effective demand with which Malthus had wrestled vanished from economic literature.[28]

The nexus between the Book IV theory and the Chapter 3 interpretation is the portrayal of the schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital as a demand function (which Hicks accepted). Hicks may be considered to have presented a General Theory free from any concept of aggregate demand.

Keynes made a similar remark in connection with Harrod’s interpretation of the General Theory soon after its publication:

You don’t mention effective demand or, more precisely, the demand schedule for output as a whole, except in so far as it is implicit in the multiplier. To me, the most extraordinary thing regarded historically, is the complete disappearance of the theory of the demand and supply for output as a whole, i.e. the theory of employment, after it had been for a quarter of a century the most discussed thing in economics.[29]

Criticisms

As travestying Keynes

Bradford DeLong denied in a blog post that ‘Mr Keynes and the Classics’ was based on the General Theory at all, viewing it instead as combining “the monetarist theories of Irving Fisher, the financial-market insights of Knut Wicksell, and the multiplier insights of Richard Kahn into one package”.[30]

Portraying the classics as more Keynesian than they really were (Keynes)

It was immediately objected to ‘Mr Keynes and the Classics’ that no classical economist had held the views attributed to the school by Hicks. Hicks was able to find a few references to wage stickiness (e.g. in Hume and Mill, quoted in the prefatory note), but admitted that “it was misleading to call that minority view the ‘classical’ theory” (id.). It is inconceivable that the classics would have seen the two IS-LM equations as constituting a system, or the Is (r ) curve as a demand function.

Keynes was nearer the truth when he wrote to Hicks, concerning his attribution of Keynesian views to the classics, that:

The story you give is a very good account of the beliefs which, let us say, you and I used to hold.[31]

Portraying Keynes as more classical than he really was

Critics of Hicks’s paper generally dissent from the ‘neoclassical synthesis’ which arose from it. Some (such as DeLong quoted above) consider Hicks to have been mistaken; others regard the error as lying in emphasis or omission.

Portraying Keynes as less classical than he really was

In attributing to Keynes the view that in realistic circumstances the interest rate might be wholly insensitive to changes in the efficiency of capital, Hicks attached to Keynesianism a more radical doctrine than can be justified from the General Theory. This reinforced conservative economists’ view of Keynes as a paradox-monger.

‘Making saving a function of money income’ (Keynes)

While broadly accepting the IS-LM formalism, Keynes pointed out an error in Hicks’s presentation owing to his decision to work in money terms. As Ambrosi writes:

Apart from the alleged misrepresentation of the Classics, one of Keynes’s criticisms of the Hicksian scheme was that he made ‘saving a function of money income’.[32]

The consequence was that a change in the value of money (e.g. a simultaneous doubling of wages and prices) would imply a change in the level of real saving according to Hicks, a result which Keynes had avoided by working in wage units. However the handling of units in Keynes’s analysis was no less problematical (see wage unit).

‘Assuming wages to be constant’ (Kahn)

Hicks wrote that ‘all expositors of Keynes’ had found the use of wage units...

... to be a difficulty.... We had to find some way of breaking the circle. The obvious way of doing so was to begin by setting out the rest... on the assumption of fixed money wages.

Kahn objected that:

The result, as Hicks points out, is the false impression that Keynes assumed wages to be constant at any level of employment short of full employment.[33]

He claimed that “Hicks’ procedure is completely unnecessary”. On the other hand it could be argued that the assumption of a given money wage rate W amounts to the assumption that the wage is fixed over the period covered by the theory. Admittedly Keynes never lists the wage rate amongst his determinants; it seems to have dropped out of sight once it had been absorbed into the units in which other values were expressed. The only way to resolve the question definitively would be to recast Keynes’s analysis in units which make the wage rate explicit (e.g. real terms) and to see whether the same results hold regardless of the behaviour of wages (which they don’t).

‘Leaving out changes in money demand’ (Ambrosi)

There is a grain of truth in criticism of the IS-LM scheme insofar as the LM part of the scheme clearly is unKeynesian in leaving out the changes in money demand generated by changes in income associated with movements along the IS curve when the rate of interest changed.[34]

This is not perfectly clear.

Unfaithful to Keynesian dynamics (Kaldor, Leijonhufvud, Kahn, Robinson)

This criticism appears in slightly different forms. Kaldor made the valid observation that Hicks’s paper makes no reference to ‘sudden variations in the MEC’, i.e. to the marginal efficiency of capital.[35]

Axel Leijonhufvud published a highly influential book in 1968 – ‘Keynesian economics and the economics of Keynes’ – criticising the direction Keynesian economics had taken under the influence of the IS-LM model. He argued that:

His [Keynes’s] followers understandably decided to skip the problematical dynamic analysis of Chapter 19 and focus on the relatively tractable static IS-LM model.[36]

The criticisms became sharper when Kahn published his ‘Making of the General Theory’ in 1984. He gave voice to his “belief that the IS-LM scheme has very seriously confused the development of economic thought”. His argument seems to have been that “Keynes’ insistence on the overwhelming importance of expectations, highly subject to risk and uncertainty, was one of his biggest contributions”, but that “Keynes’ attempt at simplification” by means of “schedules – simple relationships between two parameters” completely undermined it; and that Hicks’s formulation gave a central position to this simplification.[37]

In the same book Joan Robinson regretted that...

... modern teaching has been confused by J. R. Hicks’ attempt to reduce the General Theory to a version of static equilibrium.[38]

There are observations on uncertainty throughout the General Theory : some are purely anecdotal while others, such as those related to the trade cycle, are embodied in Keynes’s economic system (see The General Theory ). It is nonetheless the case that the analytic apparatus of the book is, as Schumpeter remarked, ‘essentially static’: [39] the account of the trade cycle itself depends heavily on the static framework. It is hard to see why an interpretation which limits itself to the static elements should be considered a source of confusion. Indeed:

when confronted with R. F. Kahn's (1984) condemnation of IS-LM, Kaldor (op. cit. p. 115) proclaimed the charges against this scheme as unsubstantiated and frankly disassociated himself from Kahn’s position.[40]

Kaldor added:

Honestly, all these years I didn’t realize what all this about IS-LM being a misrepresentation of Keynes was about...[41]

Although not very grave, the charge against Hicks that he disregarded Keynes’s dynamics is certainly accurate. He did not hold Keynes’s theory of the trade cycle in high esteem:

The record of the thirties, in major works on cycles, is outstanding, as was to be expected. I rather doubt whether Keynes’s General Theory is to be put on the list; but there is no doubt about Harrod, and Haberler, and Schumpeter; and, of course, Hayek.[42]

Inconsistent in its treatment of time (Hicks)

Hicks himself retracted his support for the IS-LM model in response to Leijonhufvud’s criticisms and subsequently wavered in his view of it. In his ‘IS-LM – an explanation’ he gave an account which allows it very limited value.

The argument of this paper is hard to follow and has not been influential. He attributes to Keynes a view which he certainly didn’t hold, namely that commodity prices as well as wages were sticky. He then finds that the concept of equilibrium consistent with this view is very tenuous, and consequently that the IS-LM model is useful only as a ‘classroom gadget’ or in analyses where ‘even a drastic use of equilibrium methods’ is ‘not inappropriate’.

The reason Hicks supposed Keynes to have assumed prices to be sticky is as follows. Keynes considered the equilibrium condition for income Y (in wage units) to be specified by two equations (which may have been an error owing to lack of care over units). He believed (probably correctly) that the resulting income might be less than what was needed for full employment. He stopped there when the problem was not fully solved: to determine the actual level of employment it would have been necessary to apply the ‘first postulate’ to find the price level and the division of income between wages and profits (as Modigliani did 8 years later). Instead, believing the significant hurdles to have been overcome, he declared that national income was ‘almost the same thing‘ as ‘the amount of its employment’.[43] This unwillingness to pursue the analysis to the bitter end was interpreted by Hicks as the adoption of a premise which would have given him a short cut.

Leijonhufvud remarked subsequently that when Hicks...

...came to explain why he had become increasingly dissatisfied with it [‘Mr Keynes and the Classics’] over the years, his reasons turned out to have almost nothing to do with the issues over which others were contending.[44]

References

- ↑ Preface to ‘Critical essays in monetary theory’.

- ↑ Brian Snowden and Howard R. Vane, ‘Conversations with modern economists’ (1999), p95.

- ↑ M. G. Ambrosi, “Keynes, Pigou and Cambridge Keynesians” (2003), p234, citing W. Young, “Interpreting Mr. Keynes. The IS-LM Enigma”, (1987), in turn citing papers by Harrod designated ‘(1937a)’ and by Meade. Meade’s paper is “A Simplified Model of Mr. Keynes’ System”. Ambrosi’s ‘(1937a)’ appears to be an error for ‘(1937b)’, which is “Mr Keynes and Traditional Theory”.

- ↑ Ambrosi, op. cit., p259.

- ↑ Richard Kahn, ‘The making of Keynes’ General Theory’ (1984), p118.

- ↑ Biography of Harrod on History of Economic Thought website.

- ↑ ‘IS-LM – an explanation.’

- ↑ Chapter 18 is avowedly a ‘restatement’ but Keynes does not make clear where any preceding statement occurred. A statement can certainly be found in Chapter 14, interleaved with Keynes’s criticisms of the classical theory of interest.

- ↑ E.g. Chapter 20.

- ↑ More precisely, the marginal prime cost is equal to the marginal product: see Appendix to Chapter 19 of the General theory.

- ↑ Article on Frederick Lavington on ‘History of economic thought’ website.

- ↑ E.g. §II of his review.

- ↑ p168.

- ↑ pp248f.

- ↑ Gordon Fletcher, ‘The Keynesian Revolution’, 1987, p126.

- ↑ “The IS-LM Model and the Liquidity Trap Concept: From Hicks to Krugman” (2004).

- ↑ “On Coddington’s Interpretation: A Reply” (1979).

- ↑ “It’s Baaack: Japan’s Slump and the Return of the Liquidity Trap”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity No. 2 (1998).

- ↑ p94.

- ↑ Kahn, “The making of the General theory ” (1984), p160.

- ↑ Prefatory note to ‘Mr Keynes and the Classics’.

- ↑ ‘Liquidity preference’ is misprinted as ‘liquidity of preference’ in ‘Critical essays in monetary theory’.

- ↑ Op. cit. p227, citing Pigou’s 1937 paper “Real and Money Wage Rates in Relation to Unemployment”.

- ↑ Op. cit., p234.

- ↑ Econometrica, 1944, reprinted in Henry Hazlitt (ed.) ‘The critics of Keynesian economics’.

- ↑ Op. cit.

- ↑ ‘Critical esssays in monetary theory’, p147.

- ↑ p32.

- ↑ Letter to R.F. Harrod, 30 August 1936.

- ↑ Mr. Hicks and "Mr Keynes and the 'Classics': A Suggested Interpretation": A Suggested Interpretation (2010).

- ↑ Gordon Fletcher, ‘The Keynesian Revolution’ (1987), p33, quoting Keynes’s collected writings, vol XIV, p79.

- ↑ Op. cit., p233, citing Keynes’s collected writings XIV, p80.

- ↑ Kahn, op. cit., p128.

- ↑ Ambrosi, op. cit., p258.

- ↑ Quoted by Ambrosi, op. cit., p232.

- ↑ Peter Howitt, English draft of entry on Leijonhufvud’s book for the Darroz ‘Dictionnaire des grandes oeuvres économiques’.

- ↑ Kahn, op. cit., pp249, 159.

- ↑ ‘Contributions to modern economics’, 1978, quoted by Kahn, op. cit., p160.

- ↑ History of economic thought.

- ↑ Ambrosi, op. cit., p232, citing Warren Young, op. cit.

- ↑ Young, op. cit., p113, cited by Ambrosi, op. cit., p232.

- ↑ ‘Are there economic cycles?’ (1981) in ‘Money, interest and wages’.

- ↑ p247.

- ↑ ‘Hicks, Keynes and Marshall’ in Hagemann and Hamouda (eds.) ‘The legacy of Hicks: his contributions to economic analysis’, 1994.