Finance:Participatory budgeting

Participatory budgeting (PB) is a process of democratic deliberation and decision-making, in which ordinary people decide how to allocate part of a municipal or public budget. Participatory budgeting allows citizens to identify, discuss, and prioritize public spending projects, and gives them the power to make real decisions about how money is spent.[1]

PB processes are typically designed to involve those left out of traditional methods of public engagement, such as low-income residents, non-citizens, and youth.[2] A comprehensive case study of eight municipalities in Brazil analyzing the successes and failures of participatory budgeting has suggested that it often results in more equitable public spending, greater government transparency and accountability, increased levels of public participation (especially by marginalized or poorer residents), and democratic and citizenship learning.[3]

The frameworks of PB differentiate variously throughout the globe in terms of scale, procedure, and objective. PB, in its conception, is often contextualized to suit a region's particular conditions and needs. Thus, the magnitudes of PB vary depending on whether it is carried out at a municipal, regional, or provincial level. In many cases, PB has been legally enforced and regulated; however, some are internally arranged and promoted. Since the original invention in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1988, PB has manifested itself in a myriad of designs, with variations in methodology, form, and technology.[4] PB stands as one of several democratic innovations such as British Columbia's Citizens' Assembly, encompassing the ideals of a participatory democracy.[5] Today, PB has been implemented in nearly 1,500 municipalities and institutions around the world.[5]

Procedure

Most broadly, all participatory budgeting schemes allow citizens to deliberate with the goal of creating either a concrete financial plan (a budget), or a recommendation to elected representatives. In the Porto Alegre model, the structure of the scheme gives subjurisdictions (neighborhoods) authority over the larger political jurisdiction (the city) of which they are part. Neighborhood budget committees, for example, have authority to determine the citywide budget, not just the allocation of resources for their particular neighborhood. There is, therefore, a need for mediating institutions to facilitate the aggregation of budget preferences expressed by subjurisdictions.

According to the World Bank Group, certain factors are needed for PB to be adopted: "[...]strong mayoral support, a civil society willing and able to contribute to ongoing policy debates, a generally supportive political environment that insulates participatory budgeting from legislators' attacks, and financial resources to fund the projects selected by citizens."[6] In addition, there are generally two approaches through which PB formulates: top-down versus bottom-up. The adoption of PB has been required by the federal government in nations such as Peru, while there are cases where local governments initiated PB independent from the national agenda such as Porto Alegre. With the bottom-up approach, NGO's and local organizations have played crucial roles in mobilizing and informing the community members.[7]

PB processes do not adhere to strict rules, but they generally share several basic steps:[8]

- The municipality is divided geographically into multiple districts.

- Representatives of the divided districts are either elected or volunteered to work with government officials in a PB committee.

- The committees are established with regularly scheduled meetings under a specific timeline to deliberate.

- Proposals, initiated by the citizens, are dealt under different branches of public budget such as recreation, infrastructure, transportation, etc.

- Participants publicly deliberate with the committee to finalize the projects to be voted on.

- The drafted budget is shared to the public and put for a vote.

- The municipal government implements the top proposals.

- The cycle is repeated on an annual basis.

History

Participatory Budgeting was first developed in the 1980s by the Brazilian Workers' Party, drawing on the party's stated belief that electoral success is not an end in itself but a spring board for developing radical, participatory forms of democracy. While there were several early experiments (including the public budgeting practices of the Brazilian Democratic Movement in municipalities such as Pelotas [9]), the first full participatory budgeting process was implemented in 1989, in the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil, a capital city of the state of Rio Grande do Sul, and a busy industrial, financial, and service center, at that time with a population of 1.2 million.[10] The initial success of PB in Porto Alegre soon made it attractive to other municipalities. By 2001, more than 100 cities in Brazil had implemented PB, while in 2015, thousands of variations have been implemented in the Americas, Africa, Asia and Europe.[11]

Porto Alegre

In its first Title, the 1988 Constitution of Brazil states that "All power originates from the people, who exercise it by the means of elected representatives or directly, according to the terms of this Constitution." The authoring of the Constitution was a reaction to the previous twenty years of military dictatorship, and the new Constitution sought to secure individual liberty while also decentralizing and democratizing ruling power, in the hope that authoritarian dictatorship would not reemerge.[12]

Brazil's contemporary political economy is an outgrowth of the Portuguese empire's patrimonial capitalism, where "power was not exercised according to rules, but was structured through personal relationships".[13] Unlike the Athenian ideal of democracy, in which all citizens participate directly and decide policy collectively, Brazil's government is structured as a republic with elected representatives. This institutional arrangement has created a separation between the state and civil society, which has opened the doors for clientelism. Because the law-making process occurs behind closed doors, elected officials and bureaucrats can access state resources in ways that benefit certain 'clients', typically those of extraordinary social or economic relevance. The influential clients receive policy favors, and repay elected officials with votes from the groups they influence. For example, a neighborhood leader represents the views of shop owners to the local party boss, asking for laws to increase foot traffic on commercial streets. In exchange, the neighborhood leader mobilizes shop owners to vote for the political party responsible for the policy. Because this patronage operates on the basis of individual ties between patron and clients, true decision-making power is limited to a small network of party bosses and influential citizens rather than the broader public.[13][14]

In 1989, Olívio Dutra won the mayor's seat in Porto Alegre. In an attempt to encourage popular participation in government and redirect government resources towards the poor, Dutra institutionalized the PT's organizational structure on a citywide level. The result is one example of what we now know as Participatory Budgeting.

Outcomes

A World Bank paper suggests that participatory budgeting has led to direct improvements in facilities in Porto Alegre. For example, sewer and water connections increased from 75% of households in 1988 to 98% in 1997. The number of schools quadrupled since 1986.[15]

The high number of participants, after more than a decade, suggests that participatory budgeting encourages increasing citizen involvement, according to the paper. Also, Porto Alegre's health and education budget increased from 13% (1985) to almost 40% (1996), and the share of the participatory budget in the total budget increased from 17% (1992) to 21% (1999).[16] In a paper that updated the World Bank's methodology, expanding statistical scope and analyzing Brazil's 253 largest municipalities that use participatory budgeting, researchers found that participatory budgeting reallocates spending towards health and sanitation. Health and sanitation benefits accumulated the longer participatory budgeting was used in a municipality. Participatory budgeting does not merely allow citizens to shift funding priorities in the short-term – it can yield sustained institutional and political change in the long term.[17]

The paper concludes that participatory budgeting can lead to improved conditions for the poor. Although it cannot overcome wider problems such as unemployment, it leads to "noticeable improvement in the accessibility and quality of various public welfare amenities".[18]

Based on Porto Alegre more than 140 (about 2.5%) of the 5,571 municipalities in Brazil have adopted participatory budgeting.[19][page needed]

Implementation & Policy Diffusion

As of 2015, over 1,500 instances of PB have been implemented across the five continents.[11] While the democratic spirit of PB remains the same throughout the world, institutional variations abound.[20]

For example, the Dominican Republic, Bolivia, Guatemala, Nicaragua, and Peru have implemented participatory budgeting in all local governments,[21][22] and a number of towns and cities in Portugal, France , Italy, Germany , and Spain have also initiated participatory budgeting processes.[23] In Canada , participatory budgeting has been implemented with public housing, neighbourhood groups, and a public schools, in the cities of Toronto,[24] Guelph, Hamilton,[25] and West Vancouver. Since its emergence in Porto Alegre, participatory budgeting has spread to hundreds of Latin American cities, and dozens of cities in Europe, Asia, Africa, and North America. In some cities, participatory budgeting has been applied for school, university, and public housing budgets. In France, the Region Poitou-Charentes is notable for launching participatory budgeting in its secondary schools.[26] These international approaches differ significantly, and they are shaped as much by their local contexts as by the Porto Alegre model.[27]

Brazil

Participatory budgeting in Porto Alegre occurs annually, starting with a series of neighborhood, regional, and citywide assemblies, where residents and elected budget delegates identify spending priorities and vote on which priorities to implement.[28] Porto Alegre spends about 200 million dollars per year on construction and services, this money is subject to participatory budgeting. Annual spending on fixed expenses, such as debt service and pensions, is not subject to public participation. Around fifty thousand residents of Porto Alegre now take part in the participatory budgeting process (compared to 1.5 million city inhabitants), with the number of participants growing year on year since 1989. Participants are from diverse economic and political backgrounds.[28]

The participatory budgeting cycle starts in January and assemblies across the city facilitate maximum participation and interaction. Each February there is instruction from city specialists in technical and system aspects of city budgeting. In March there are plenary assemblies in each of the city's 16 districts as well as assemblies dealing with such areas as transportation, health, education, sports, and economic development. These large meetings—with participation that can reach over 1,000—elect delegates to represent specific neighborhoods. The mayor and staff attend to respond to citizen concerns. In the following months, delegates meet weekly or biweekly in each district to review technical project criteria and district needs. City department staff may participate according to their area of expertise. At a second regional plenary, regional delegates prioritize the district's demands and elect 42 councillors representing all districts and thematic areas to serve on the Municipal Council of the Budget. The main function of the Municipal Council of the Budget is to reconcile the demands of each district with available resources, and to propose and approve an overall municipal budget. The resulting budget is binding, though the city council can suggest, but not require changes. Only the Mayor may veto the budget, or remand it back to the Municipal Council of the Budget (this has never happened).[28]

United States of America

The first recorded Participatory Budgeting process in the United States of America is in the Rogers Park neighborhood of Chicago , Illinois.[29][30] Led by the ward's Alderman, Joe Moore, Chicago's 49th Ward is undertaking this process[31] with the Alderman's "Menu Money." Menu Money is a yearly budgeted amount each of Chicago's 50 wards receives for use on capital expenses. This money in other wards is typically allocated at the complete discretion of a ward's Alderman. Since 2011 more examples have been occurring in the US, in New York City ,[32] and now citywide in Vallejo, California,[33] and most recently in Greensboro, NC.[34] In Boston, the first youth-led participatory budgeting process in the US allows teens to decide how to spend $1 million of the city's budget.[35]

Municipal Processes

Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge's first PB occurred in 2014-2015, with $528,000 allocated towards the implementation of six winning projects. Winning projects included one hundred healthy trees, twenty laptops for a community center, bilingual books for children learning english, a public bathroom in Central Square, bike report stations, and free public wifi in six outdoor locations.

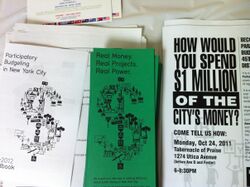

New York City

New York City's Participatory Budgeting process (PBNYC) is the largest in North America.[36] The process began in 2011-2012 as a pilot program in four City Council districts.[37] In its sixth year (2016-2017), PBNYC has grown to include 31 of the city's 51 districts. Community members in each district decide how to spend at least $1 million of their City Council member's discretionary funds.[38]

PBNYC cycles run from early fall through the spring. Districts hold neighborhood meetings to collect ideas for community improvement projects. Idea collection is focused particularly on hard-to-reach communities, such as immigrants with limited English proficiency, youth, senior citizens, and public housing residents. Volunteers then research community needs and work with city agencies to turn ideas into concrete proposals. The proposals are put to a community vote, which is open to any resident of the district over the age of 14. City agencies implement the winning projects.[38]

Housing Complex Processes

Toronto

In Toronto Community Housing, PB is part of a broader "tenant participation system." PB has been a part of Toronto Community Housing since 2001. This inspired the launch of a three-year pilot of PB at the ward-level in Toronto, beginning in 2015. In the months of May and June 2018 the city will begin debating what to do with PB at the municipal-level, following annual evaluations of the pilot. Thirty-seven projects have been voted for through the entirety of the three-year pilot process, comprising a total of $1.8 million in residents directly allocating funds towards projects.

New York City

Citing the case of Toronto, Community Voices Heard (CVH) has called for PB within the New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA). As part of a platform for democratizing and improving access to public housing, CVH has advocated for developing a kind of participatory system tied together by PB. CVH also advocates for a gradual increase of money being allocated through PB as residents become increasingly familiarized with the process.

Los Angeles

As part of a broader platform for pushing greater investment and public housing, in early 2014 the LA Human Right to Housing collective began advocating for the use of PB in the Housing Authority of the City of Los Angeles (HACLA). This was in response to a budget corruption scandal in November 2012 in HACLA.According to the Collective, nearly one-hundred residents mobilized to demand PB at a HACLA Agency Plan hearing in August 2014. In response, HACLA launched a "values driven participatory budgeting process" developed and coordinated by a consultant. This was a six-week process, consisting of "resident consultation" that fed into decisions ultimately made by administration and management. Participatory elements of the process were "a resident survey" and "resident review of site specific budgets." The Collective regarded both the design and distribution of the survey to be unsatisfactory. Coupled with a lack of technical support, any kind of resident-focused collective deliberation or evidence of resident influence on the outcome of the process, the Collective deemed the process "participatory in name only."

To counter this, the Collective sought to scale up their campaign for a "true participatory budgeting" process by initiating a Model PB process. The process included a combination of one-on-one and door-to-door outreach with deliberation through meetings and assemblies of residents. The Model PB process resulted in tenants and the Collective deepening their critique of HACLA's PB "in name only" as well as putting forward a number of recommendations to create a "true PB" process.

Youth, School, and College Processes

Greater Boston Area

Since 2014 a youth PB process has operated in the city of Boston. Today the process allows persons aged between 12 and 25 years old to decide how to allocate one million dollars.

In 2013-2014 MIT's International Development Group within the school's Department of Urban Studies and Planning conducted an $8,000 PB process. Voting was not over allocating money to specific project proposals, but rather to determining exact allotments to four broad distinct budget categories: field trips, social events, project funding, and cultural event series. To determine precise allotments, "each participant allocated a percentage value of the $8,000 to each category. The average for each category was taken and a preliminary set of results was disclosed." The MIT intra-departmental process provides an example of how PB can be utilized to not only determine the allocation of funds within a specific budget category, but also to determine how funds are distributed across budget categories.

Chicago

In Spring 2015 Sullivan High School conducted a $25,000 participatory budgeting process. Seventy percent of the student body voted in the process, with the money allocated towards building a new recreation room.

New York

Within PBNYC youth participation has been semi-formalized in various forms. This includes the youth-led formation of the District 39 PB Youth Committee. District 3 also possesses a PB Youth Committee December 2015, which works in collaboration with an organization called Friends of the High Line. In his State of the City address, Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that PB would be launched in every public high school. Each participating school will receive $2,000 for students to allocate through PB. PB has also been launched at various colleges in the City University of New York. These have included Queens College, Brooklyn College, City Tech, Hunter College, and the CUNY Graduate Center.

Phoenix

Ten high schools allocated $55,000 of district-wide funds in Phoenix through PB.

San Antonio

In 2013 a $25,000 PB process was launched at Palo Alto Community College. Initially this was only open to faculty and staff. In fall 2015 the process was opened to students as well. The 2018 process expanded the pot of funds from $25,000 to $50,000.

United Kingdom

PB in the United Kingdom was initially introduced as part of the 'New Labour' Party's decentralization agenda that aimed to empower the local governments in the first decade of the 21st century.[39] Hazel Blears, the Labour MP, "[...] played a key role in the inclusion of PB on the national policy agenda[...]," pushing for greater community participation and empowerment in the governmental structure.[40] Within this new political ambiance, the British PB, inspired by Porto Alegre's example, gained traction for implementation, especially through the active engagement of local NGO's and community activists, namely the Community Pride Initiative.[41]

The first attempt at PB was initiated as a pilot in the city of Bradford in 2004, and its "procedural model consists of two main steps: the elaboration of project schemes by local community groups and a decision about these schemes by all involved groups during a public meeting."[42] The Bradford process, while limited to small funding, helped PB spread to other cities such as Newcastle.[42] In addition to the bottom-up activism in local communities, Blears's initiative for PB on the national level helped promote its implementation and diffusion more broadly, and by 2011, there were at least 150 recorded cases of PB, albeit being limited to small funding and designated personnel.[43] The "UK style" of PB, as Anja Rocke puts it, "in form of small grant-spending processes with no secured financial basis and organized at the margins of the political system," failed to gain enough momentum to be established nationally as a formal decision-making procedure.[44]

Scotland

The Scottish Government has made a commitment to participatory budgeting, saying "We support PB as a tool for community engagement and for developing participatory democracy in Scotland".[45] In addition, the Scottish Government and the Convention of Scottish Local Authorities have agreed that at least 1% of local government budgets will be subject to participatory budgeting by the end of 2021, potentially amounting to £100million.[46]

The Scottish Government allocates funding for participatory budgeting through the Community Choices Fund, delivered in partnership between the Government, local authorities, communities and third sector organisations.

| Year | Funds allocated |

|---|---|

| 2016-2017 | £1.5 million |

| 2017-2018 | £2 million |

Support and tools

There is a national network to support participatory budgeting called the PB Scotland Network. Glasgow Community Planning Partnership has worked with What Works Scotland to develop a toolkit to assess the impact of its PB activities and develop an improvement plan.[47]

Review and evaluation

A number of analyses and reviews of participatory budgeting in Scotland have been published since 2015, including:

Participatory budgeting in Scotland: an overview of strategic design choices and principles for effective delivery. Produced by What Works Scotland and the Glasgow Centre for Population Health, this reviewed international research, evaluations, grey literature and commentary and drew upon learning and insights from a PB pilot in Govanhill in Glasgow.[48] (Published December 2015).

A Review of First Generation Participatory Budgeting in Scotland. This examined the growth and development of the first generation of participatory budgeting in Scotland in order to generate insight to support the strategic and operational leadership and delivery of future participatory budgeting. The review was commissioned by What Works Scotland and was undertaken by researchers from the Glasgow Centre for Population Health and What Works Scotland.[49] (Published October 2016).

Public service reform and participatory budgeting: How can Scotland learn from international evidence? A documentary film exploring how Glasgow and Fife community planning partnerships learnt about implementing participatory budgeting on a study trip to Paris, a European leader in mainstreaming PB.[50] (Published July 2017)

Evaluating Participatory Budgeting Activity in Scotland – Interim Report Year 2. Produced by researchers based at Glasgow Caledonian University for the Scottish Government. It identified any impact that PB has had on local communities, local services, and local democracy in Scotland across 20 local authority areas with a more detailed analysis of 6 local authorities.[51](Published Nov 2017).

Republic of Korea

In 2005, the national government revised its Local Finance Act to promote citizen participation in the local government budgeting process in response to a few of the local governments that initially took a bottom-up approach in experimenting with forms of PB.[52] Since then, the Ministry of Security and Public Administration invested in the nation-wide promotion of PB system diffusion, and under Myung Bak Lee's Administration in 2011, the newly revised Local Finance Act required all local governments to adopt PB.[52]

Before the 2011 decree, approximately 45% of local governments had already been utilizing the PB system, and it took 3 years for the remaining municipalities to fulfill the mandate.[52] The PB System of Seoul Metropolitan Government served as the benchmark for other local governments' adoption of PB in those years.[52] Seoul, city with the world's 4th highest GDP, runs a PB committee of 300 people representing 25 districts. The committee is then split into 11 different budgetary fields such as parks and recreation, culture, environment, and etc. In its first year, Seoul citizens voted and finalized on 223 projects worth 50.3 billion KRW, and most recently in 2017, the PB system finalized 766 projects amounting to 59.3 billion KRW (approximately 55 million USD).[53]

A comprehensive study of Korea's PB in 2016 suggests that PB in Korea has allocated most of public budget to the following three areas: land/local development, transportation, and culture and tourism. Transparency in budget documents and information sharing has increased since 2011, and the approval rates by local PB committees averaged to approximately 70%. On the other hand, the study also points out that the lack of citizen capacity, inadequate resources for smaller municipalities, and limited representativeness of vested interests as some of the most unresolved challenges in Korea's PB implementation.[52]

India

India's experience with PB has been limited despite its 74th Constitutional Amendment, which proposes to the state and local governments the formation of ward committees composed of local citizens to direct ward-level budgets.[54] Such initiative was not implemented, and thus there were only few cities that experimented with PB, which are Bangalore, Myso, Pune, and Hiware Bazar.[55]

Bangalore was the first to implement PB in India in 2001 with the help of a local NGO. Similarly, Pune was able to adopt PB in 2006 with the help of several local NGOs. Pune's PB system was met with a large response from its local citizens, and multiple online and offline workshops were carried out to foster the implementation.[56] As a result, Pune has experienced both increased citizen participation and budget allocation, which are directed primarily towards roads, electricity, slum-improvement, and water shortage.[57] Influenced by Pune's PB, Pimpri-Chinchwad, the fifth-most populated city of Maharashtra, also began to adopt the framework soon after.[58]

Hiware Bazar may have served as the most successful example of PB in India. On June 25, 2015, Delhi Deputy chief Minister Manish Sisodia presented the Swaraj Budget.[59] The Aam Admi Party Swaraj Budget was prepared based on voting from the people of different constituencies. In each constituency three meetings were held; each meeting was attended by 200–300 residents, and a list of key issues was prepared, which was then voted on to decide the top priorities.[60][61][62] As a result, the village, once bereft of water, education, and basic needs for life, is now self-sufficient with a high per capita income.[63]

South Africa

For South Africa, the mechanisms for citizen participation is written in its constitution. Each municipality has its budgetary committee formed with representatives from its 'wards' that deal directly with its budgeting.[64] The World Bank Group's research lists Mangaung and Ekurhuleni municipalities as representative cases to demonstrate the typical PB process in South Africa.[65] First, the process for the council is fixed by the mayor, who sets up certain deadlines for the council to deliberate within.[66] Then, the municipality is divided geographically into 'wards', and the public budget is drawn with any desired submission from the community through their ward representatives.[66] The tentatively accumulated budget plan is then publicized so that any citizens or "stakeholders" can make their final inputs, and the final version is submitted to the national and provincial governments for approval.[66]

On a nation-wide level, the South African municipalities, as a result of PB, have witnessed the public budget "shift from infrastructure development to local economic development, a higher priority for citizens."[67] Currently, PB is being carried out in 284 municipalities, each varying slightly in its process.[68] The rate of transparency for the municipal governments has increased because the sub-organization ward committees are able to maintain consistently ongoing communication with the citizens.[69] Regardless, the challenges in South African local governance still prevail as a result of the lack of resources and limited capacities assigned to PB. Furthermore, language barriers and cultural differences also provide immediate obstacles for holistic communications between various wards and social groups within the municipalities.[70]

Iceland

The Better Neighbourhoods participatory budgeting project of the wider citizen sourcing Better Reykjavik project of the City of Reykjavik was established in 2011. Nearly 2 million Euros (300 million ISK) has been allocated each year with over citizen proposed 100 projects funded most years. The project is mostly driven by digital participation with secure electronic voting.[71][72]

Buenos Aires

Buenos Aires adopted the PB process in 2001 hoping to emerge a political economy. There were manipulators like people watching the system and third parties forming for or against the PB system. Buenos aires used a system where the communities allocated where the government would take action first by ranking where the cities resources would go. After participation decreased by 50% in the 2005 cycle, PB came to an end and "the new communes" emerged.[11]

Criticism

Reviewing the experience in Brazil and Porto Alegre a World Bank paper points out that lack of representation of extremely poor people in participatory budgeting can be a shortcoming. Participation of the very poor and of the young is highlighted as a challenge.[73] What are the insights regarding the opportunities for and barriers to accomplishing the goal of participatory-based budgeting? It takes leadership to flatten the organizational structure and make conscious ethical responsibilities as individuals and as committee members try to achieve the democratic goals means that the press should be present for the public, and yet the presence of the press inhibits the procedural need for robust discussion. Or, while representation is a cornerstone to participatory budgeting, a group being so large has an effect on the efficiency of the group. Participatory budgeting may also struggle to overcome existing clientelism. Other observations include that particular groups are less likely to participate once their demands have been met and that slow progress of public works can frustrate participants.[19][page needed]

In Chicago, participatory budgeting has been criticized for increasing funding to recreational projects while allocating less to infrastructure projects.[74]

See also

- Participatory democracy

- Deliberative poll

- Citizens' assembly

- Participatory economics

- Participatory planning

- Participatory justice

- Programme budgeting

- Public participation

- Tax choice

References

- ↑ Chohan, Usman W. (2016-04-20). "The 'citizen budgets' of Africa make governments more transparent" (in en-US). https://theconversation.com/the-citizen-budgets-of-africa-make-governments-more-transparent-58275.

- ↑ "Mission & Approach" (in en-US). 2012-09-20. http://www.participatorybudgeting.org/who-we-are/mission-approach/.

- ↑ "Participatory Budgeting in Brazil". PSUpress. http://www.psupress.org/books/titles/978-0-271-03252-8.html.

- ↑ Porto de Oliveira, Osmany (January 10, 2017). Internatioanl Policy Diffusion and Participatory Budgeting: Ambassadors of Participation, International Institutional and Transnational Networks. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature. ISBN 978-3-319-43337-0.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Röcke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9781137326669. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. The World Bank. pp. 92. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-6923-4. ISBN 0-8213-6923-7.

- ↑ Wainwright, H. (2003). Making a People's Budget in Porto Alegre. NACLA Report On The Americas. pp. 36(5), 37–42.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 ""How Participatory Budgeting Travels the Globe" by Ernesto Ganuza and Gianpaolo Baiocchi". http://www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol8/iss2/art8/. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ Abers, Jessica (1998). "From Clientelism to Cooperation: Local Government, Participatory Policy, and Civic Organizing in Porto Alegre, Brazil". Politics & Society 26: 516. doi:10.1177/0032329298026004004. http://pas.sagepub.com/content/26/4/511.short. Retrieved 15 November 2015.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Novy, Andreas; Leubolt, Bernhard (2005-10-01). "Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Social Innovation and the Dialectical Relationship of State and Civil Society". Urban Studies 42 (11): 2023–2036. doi:10.1080/00420980500279828. ISSN 0042-0980. http://usj.sagepub.com/content/42/11/2023.

- ↑ Santos, BOAVENTURA de SOUSA (1998-12-01). "Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Toward a Redistributive Democracy". Politics & Society 26 (4): 461–510. doi:10.1177/0032329298026004003. ISSN 0032-3292. http://pas.sagepub.com/content/26/4/461.

- ↑ Bhatnagar et al. 2003, p. 2.

- ↑ Bhatnagar et al. 2003, p. 3.

- ↑ "Improving Social Well-Being Through New Democratic Institutions". http://cps.sagepub.com/content/47/10/1442.full?keytype=ref&siteid=spcps&ijkey=qPmuzabskSFkQ. Retrieved September 29, 2015.

- ↑ Bhatnagar et al. 2003, p. 1.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Bhatnagar et al. 2003.

- ↑ "Budgets for the People". https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2015-03-11/budgets-people. Retrieved 2015-11-17.

- ↑ "History". The Participatory Budgeting Project. http://www.watsonblogs.org/participatorybudgeting/historypb.html.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ (in de) (PDF) Volumen zwei: Endbericht Bürgerhaushalt Europa 5, Germany: Bürgerhaushalt Europa, http://www.buergerhaushalt-europa.de/documents/Volumen_zwei_Endbericht_Buergerhaushalt_Europa5.pdf.

- ↑ "Participatory Budgeting – Working together, making a difference". Toronto Community Housing. http://www.torontohousing.ca/participatory_budgeting.

- ↑ PB Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, http://pbhamont.ca/.

- ↑ "Poitou-Charentes' participatory budget in the high schools", Participedia, http://www.participedia.net/wiki/Poitou-Charentes%27_participatory_budget_in_the_highschools.

- ↑ (PDF) Participatory budgeting, United Kingdom: CFE, http://www.cfe.org.uk/uploaded/files/Participatory%20Budgeting.pdf.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Lewit, David (December 31, 2002). "Porto Alegre's Budget Of, By, and For the People". Yes! Magazine. http://www.yesmagazine.org/article.asp?ID=562.

- ↑ "Chicago's $1.3 Million Experiment in Democracy". The Permaculture Research Institute. 2010-05-27. http://permaculture.org.au/2010/05/27/chicagos-1-3-million-experiment-in-democracy/.

- ↑ "Chicago's $1.3 Million Experiment in Democracy; For the First Time in the US, the City's 49th Ward Lets Taxpayers Directly Decide How Public Money is Spent", Yes Magazine, April 10, 2010, http://www.yesmagazine.org/people-power/chicagos-1.3-million-experiment-in-democracy.

- ↑ "Participatory budgeting". 49th Ward. http://www.ward49.com/participatory-budgeting/. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Participatory budgeting in New York City". http://pbnyc.org/. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ↑ "Participatory budgeting city wide in Vallejo, CA". Public policy. Pepperdine. http://publicpolicy.pepperdine.edu/davenport-institute/incommon/index.php/2012/04/city-wide-pb-in-vallejo-ca/. Retrieved April 20, 2015.

- ↑ "City of Greensboro NC: Participatory Budgeting". City of Greensboro. http://www.greensboro-nc.gov/index.aspx?page=4796. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- ↑ "Participatory Budgeting Boston" (in en-US). https://youth.boston.gov/youth-lead-the-change/.

- ↑ "Speaker Melissa Mark-Viverito and New York City Council Launch 2015-2016 Participatory Budgeting Cycle". http://council.nyc.gov/html/pr/092115launch.shtml.

- ↑ "Examples of PB" (in en-US). http://www.participatorybudgeting.org/about-participatory-budgeting/examples-of-participatory-budgeting/.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "Participate". http://labs.council.nyc/pb/participate/.

- ↑ Rocke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 87. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- ↑ Rocke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 94. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- ↑ Rocke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Rocke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 100. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- ↑ Rocke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- ↑ Rocke, Anja (2014). Framing Citizen Participation: Participatory Budgeting in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom. London, United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 162. ISBN 978-1-137-32666-9.

- ↑ "Community empowerment: Participatory budgeting - gov.scot" (in en). https://beta.gov.scot/policies/community-empowerment/participatory-budgeting/.

- ↑ "More choice for communities" (in en). https://news.gov.scot/news/more-choice-for-communities.

- ↑ "Glasgow's Participatory Budgeting Evaluation Toolkit | What Works Scotland" (in en-US). http://whatworksscotland.ac.uk/publications/glasgows-participatory-budgeting-evaluation-toolkit/.

- ↑ "Participatory budgeting in Scotland: an overview of strategic design choices and principles for effective delivery | What Works Scotland" (in en-US). http://whatworksscotland.ac.uk/publications/participatory-budgeting-in-scotland-an-overview-of-design-choices-and-principles/.

- ↑ "Review of First Generation Participatory Budgeting in Scotland | What Works Scotland" (in en-US). http://whatworksscotland.ac.uk/publications/review-of-first-generation-participatory-budgeting-in-scotland/.

- ↑ "Public service reform and participatory budgeting: How can Scotland learn from international evidence? | What Works Scotland" (in en-US). http://whatworksscotland.ac.uk/publications/public-service-reform-how-can-scotland-learn-from-international-evidence/.

- ↑ Scottish Government, St Andrew's House (2017-11-10). "Evaluating Participatory Budgeting Activity in Scotland – Interim Report Year 2" (in English). http://www.gov.scot/Publications/2017/11/8658.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 Kim, Soonhee (January 2016). Participatory Governance and Polcy Diffusion in Local Governments in Korea: Implementation of Participatory Budgeting. Sejong-si, Korea: Korea Development institute. ISBN 979-11-5932-106-1.

- ↑ "참여예산제". 서울특별시청. http://yesan.seoul.go.kr/intro/index.do. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Keruwala, Naim (June–August 2013). "Participatory Budgeting in India-The Pune Experiment". The Budget Bulletin (National Foundation for India) V. http://www.nfi.org.in/sites/default/files/newsletter/THE%20BUDGET%20BULLETIN_1.pdf. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Keruwala, Naim (June–August 2013). "Participatory Budgeting in India-The Pune Experiment". The Budget Bulletin (National Foundation for India) V. http://www.nfi.org.in/sites/default/files/newsletter/THE%20BUDGET%20BULLETIN_1.pdf. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Keruwala, Naim (June–August 2013). "Participatory Budgeting in India-The Pune Experiment". The Budget Bulletin (National Foundation for India) V. http://www.nfi.org.in/sites/default/files/newsletter/THE%20BUDGET%20BULLETIN_1.pdf. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Keruwala, Naim (June–August 2013). "Participatory Budgeting in India-The Pune Experiment". The Budget Bulletin (National Foundation for India) V. http://www.nfi.org.in/sites/default/files/newsletter/THE%20BUDGET%20BULLETIN_1.pdf. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Keruwala, Naim (June–August 2013). "Participatory Budgeting in India-The Pune Experiment". The Budget Bulletin (National Foundation for India) V. http://www.nfi.org.in/sites/default/files/newsletter/THE%20BUDGET%20BULLETIN_1.pdf. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ↑ Highlights of Swaraj budget presented by deeputy CM SH Manish Sisodia, Aam Admi party, http://www.aamaadmiparty.org/highlights-of-swaraj-budget-presented-by-deputy-cm-sh-manish-sisodia.

- ↑ "Aam Admi gives Swaraj budget a thumbs up", The Times of India (India Times), http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/delhi/Aam-aadmi-gives-Swaraj-budget-a-thumbs-up/articleshow/46981634.cms.

- ↑ "Swaraj". Books. Google. https://books.google.com/books?hl=en&lr=&id=qk6YyKRRIk0C&oi=fnd&pg=PT3.

- ↑ "Goal of Swaraj". Aam Aadmi Party. http://www.aamaadmiparty.org/page/goal-of-swaraj.

- ↑ Dhara, Sagar. "Including People in Governance". The Hindu. http://www.thehindu.com/todays-paper/tp-opinion/including-people-in-governance/article6483234.ece. Retrieved 16 April 2018.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. pp. 207–208. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. p. 213. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ Shah, Anwar (2007). Participatory Budgeting. Washington D.C.: The World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-6924-1. https://siteresources.worldbank.org/PSGLP/Resources/ParticipatoryBudgeting.pdf. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ↑ "Better Neighborhoods 2011 to 2015" (in en-US). http://www.citizens.is/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Better-Neighbourhoods-Participatory-budgeting-in-Reykjavik-2011-2015.pdf.

- ↑ "The world watches Reykjavik's digital democracy experiment" (in en-US). Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/754a9442-af7b-11e7-8076-0a4bdda92ca2.

- ↑ Bhatnagar et al. 2003, p. 5.

- ↑ "The Pitfalls of Participatory Budgeting" (in en). Chicago Tonight | WTTW. http://chicagotonight.wttw.com/2017/04/24/pitfalls-participatory-budgeting.

Bibliography

- Bhatnagar, Prof. Deepti; Rathore, Animesh; Torres, Magüi Moreno; Kanungo, Parameeta (2003) (PDF), Participatory Budgeting in Brazil, Ahmedabad; Washington, DC: Indian Institutes of Management; World Bank, http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTEMPOWERMENT/Resources/14657_Partic-Budg-Brazil-web.pdf.

- Sintomer, Yves; Herzberg, Carsten; Röcke, Anja (2008) (PDF), From Porto Alegre to Europe: Potentials and Limitations of Participatory Budgeting, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, http://www.delog.org/cms/upload/pdf/participatory_budgeting.pdf.

- Geissel, Brigitte; Newton, Kenneth (2012), Evaluating Democratic Innovations: Curing the Democratic Malaise?, Routledge, https://books.google.com/books?id=ikLRWoy7b34C&printsec=frontcover&source=gbs_atb#v=onepage&q&f=false.

- Gilman, Hollie Russon (2012) (PDF), Transformative Deliberations: Participatory Budgeting in the United States, Journal of Public Deliberation, http://www.publicdeliberation.net/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1237&context=jpd.

- Gilman, Hollie Russon (2016) (PDF), Engaging Citizens: Participatory Budgeting and the Inclusive Governance Movement within the United States, Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation, Harvard Kennedy School, http://ash.harvard.edu/files/ash/files/participatory-budgeting-paper.pdf?m=1455295224.

- Novy, Andreas; Leubolt, Bernhard (2005) (PDF), Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Social Innovation and the Dialectical Relationship of State and Civil Society, Urban Studies, http://usj.sagepub.com/content/42/11/2023.short.

- Goldfrank, Benjamin (2006) (PDF), Lessons from Latin American Experience in Participatory Budgeting, San Juan, Puerto Rico: ResearchGate, https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Goldfrank_Benjamin/publication/253455515_Lessons_from_Latin_American_Experience_in_Participatory_Budgeting/links/54e232b20cf2c3e7d2d30d20.pdf.

- Avritzer, Leonardo (2006), "New Public Spheres in Brazil: Local Democracy and Deliberative Politics" (PDF), International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 30: 623–637, doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00692.x, http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2006.00692.x/epdf.

- de Sousa Santos, Boaventura (1998) (PDF), Participatory Budgeting in Porto Alegre: Toward a Redistributive Democracy, Politics & Society, http://pas.sagepub.com/content/26/4/461.full.pdf+html.

- Souza, Celina (2001) (PDF), Participatory budgeting in Brazilian cities: limits and possibilities in building democratic institutions, Environment & Urbanization, http://eau.sagepub.com/content/13/1/159.short.

- Cabannes, Yves (2004) (PDF), Participatory budgeting: a significant contribution to participatory democracy, Environment & Urbanization, http://eau.sagepub.com/content/16/1/27.short.

- Abers, Rebecca (1998) (PDF), From Clientelism to Cooperation: Local Government, Participatory Policy, and Civic Organizing in Porto Alegrem Brazil, Politics & Society, http://pas.sagepub.com/content/26/4/511.short.

External links

- Participatory budgeting initiatives around the world, Google, https://maps.google.com/maps/ms?ie=UTF8&hl=en&msa=0&msid=210554752554258740073.00045675b996d14eb6c3a&ll=6.839971,28.205177&spn=170.959424,24.609375&z=1.

- The Participatory Budgeting Project, http://www.participatorybudgeting.org/ – a non-profit organization that supports participatory budgeting in North America and hosts an international resource site.

- PBnetwork UK - information on participatory budgeting in the UK

- PB Scotland- Support to implement PB in Scotland

- Participatory budgeting publications and resources from What Works Scotland

- Digital tools and participatory budgeting in Scotland from The Democratic Society

- Budget Participatif Paris - PB website for the City of Paris

- Case study on the Electronic Participatory Budgeting of the city of Belo Horizonte (Brazil)

- Study with cases of Participatory Budgeting experiences in OECD countries

- www.citymayors.com - PB in Brazil

- Electronic Participatory Budgeting in Iceland - Case study

- PB in Rosario, Argentina Official Site of PB in Rosario, Argentina (Spanish).

- www.chs.ubc.ca/participatory - links to participatory budgeting articles and resources

- http://fcis.oise.utoronto.ca/~daniel_schugurensky/lclp/poa_vl.html - links to participatory budgeting articles and resources

- Participatory Budgeting Facebook Group - large participatory budgeting online community

- www.nuovomunicipio.org - Rete del Nuovo Municipio, the Italian project linking Local Authorities, scientists and local committees for promoting Participatory Democracy and Active Citizenship mainly by way of PB

- "Experimentos democráticos. Asambleas barriales y Presupuesto Participativo en Rosario, 2002-2005" - Doctoral Dissertation of Alberto Ford on Participatory Budgeting in Rosario, Argentina (Spanish).

- "More generous than you would think": Giovanni Allegretti shares insight of PB in an interviews with D+C/E+Z's Eva-Maria Verfürth, EU: DANDC, http://www.dandc.eu/en/article/participatory-budgeting-about-every-voice-being-hear.

- An interview with Josh Lerner, Executive Director of the Participatory Budgeting Project

- Participatory budgeting site of Cambridge, Massachusetts