Geometric integrator

In the mathematical field of numerical ordinary differential equations, a geometric integrator is a numerical method that preserves geometric properties of the exact flow of a differential equation.

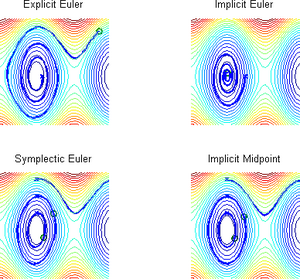

Pendulum example

We can motivate the study of geometric integrators by considering the motion of a pendulum.

Assume that we have a pendulum whose bob has mass and whose rod is massless of length . Take the acceleration due to gravity to be . Denote by the angular displacement of the rod from the vertical, and by the pendulum's momentum. The Hamiltonian of the system, the sum of its kinetic and potential energies, is

which gives Hamilton's equations

It is natural to take the configuration space of all to be the unit circle , so that lies on the cylinder . However, we will take , simply because -space is then easier to plot. Define and . Let us experiment by using some simple numerical methods to integrate this system. As usual, we select a constant step size, , and for an arbitrary non-negative integer we write . We use the following methods.

- (explicit Euler),

- (implicit Euler),

- (symplectic Euler),

- (implicit midpoint rule).

(Note that the symplectic Euler method treats q by the explicit and by the implicit Euler method.)

The observation that is constant along the solution curves of the Hamilton's equations allows us to describe the exact trajectories of the system: they are the level curves of . We plot, in , the exact trajectories and the numerical solutions of the system. For the explicit and implicit Euler methods we take , and z0 = (0.5, 0) and (1.5, 0) respectively; for the other two methods we take , and z0 = (0, 0.7), (0, 1.4) and (0, 2.1).

The explicit (resp. implicit) Euler method spirals out from (resp. in to) the origin. The other two methods show the correct qualitative behaviour, with the implicit midpoint rule agreeing with the exact solution to a greater degree than the symplectic Euler method.

Recall that the exact flow of a Hamiltonian system with one degree of freedom is area-preserving, in the sense that This formula is easily verified by hand. For our pendulum example we see that the numerical flow of the explicit Euler method is not area-preserving; viz.,

A similar calculation can be carried out for the implicit Euler method, where the determinant is

However, the symplectic Euler method is area-preserving:

thus . The implicit midpoint rule has similar geometric properties.

To summarize: the pendulum example shows that, besides the explicit and implicit Euler methods not being good choices of method to solve the problem, the symplectic Euler method and implicit midpoint rule agree well with the exact flow of the system, with the midpoint rule agreeing more closely. Furthermore, these latter two methods are area-preserving, just as the exact flow is; they are two examples of geometric (in fact, symplectic) integrators.

Moving frame method

The moving frame method can be used to construct numerical methods which preserve Lie symmetries of the ODE. Existing methods such as Runge-Kutta can be modified using moving frame method to produce invariant versions.[1]

See also

References

- ↑ Pilwon Kim (2006), " Invariantization of Numerical Schemes Using Moving Frames"

Further reading

- Hairer, Ernst; Lubich, Christian; Wanner, Gerhard (2002). Geometric Numerical Integration: Structure-Preserving Algorithms for Ordinary Differential Equations. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3-540-43003-2.

- Leimkuhler, Ben; Reich, Sebastian (2005). Simulating Hamiltonian Dynamics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77290-7.

- Budd, C.J.; Piggott, M.D. (2003). "Geometric Integration and its Applications". 11. Elsevier. pp. 35–139. doi:10.1016/S1570-8659(02)11002-7. ISBN 9780444512475.

- Kim, Pilwon (2007). "Invariantization of Numerical Schemes Using Moving Frames". 47. Springer. pp. 525–546. doi:10.1007/s10543-007-0138-8.

|