History:Goryeo

Goryeo (Template:Korean/auto; Middle Korean: 고ᇢ롕〮, romanized: kwòwlyéy) was a Korean state founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until the establishment of Joseon in 1392.[1] Goryeo achieved what has been called a "true national unification" by Korean historians as it not only unified the Later Three Kingdoms but also incorporated much of the ruling class of the northern kingdom of Balhae, who had origins in Goguryeo of the earlier Three Kingdoms of Korea.[2][3] According to Korean historians, it was during the Goryeo period that the individual identities of Goguryeo, Baekje and Silla were successfully merged into a single entity that became the basis of the modern-day Korean identity.[4][5] The name "Korea" is derived from the name of Goryeo, also romanized as Koryŏ, which was first used in the early 5th century by Goguryeo;[4] Goryeo was a successor state to Later Goguryeo and Goguryeo.[6][7][8][9]

Goryeo was established in 918 when general Wang Kŏn, after rising under the erratic Taebong ruler Kung Ye, was chosen by fellow generals to replace him and restore stability. Throughout its existence, Goryeo, alongside Unified Silla, was known to be the "Golden Age of Buddhism" in Korea.[10] As the state religion, Buddhism achieved its highest level of influence in Korean history, with 70 temples in the capital alone in the 11th century.[11] Commerce flourished in Goryeo, with merchants coming from as far as the Middle East.[12][13] The capital in modern-day Kaesong, North Korea was a center of trade and industry.[14] Goryeo was a period of great achievements in Korean art and culture.[15]

During its heyday, Goryeo constantly wrestled with northern empires such as the Liao (Khitans) and Jin (Jurchens). It was invaded by the Mongol Empire and became a vassal state of the Yuan dynasty in the 13th–14th centuries,[16] but attacked the Yuan and reclaimed territories as the Yuan declined.[17] This is considered by modern Korean scholars to be Goryeo's Northern Expansion Doctrine (북진 정책) to reclaim ancestral lands formerly owned by Goguryeo.[18] As much as it valued education and culture, Goryeo was able to mobilize sizable military might during times of war.[19][20] It fended off massive armies of the Red Turban Rebels from China[21][22] and professional Japanese pirates[23][24] in its twilight years of the 14th century.[25] A final proposed attack against the Ming dynasty resulted in a coup d'état led by General Yi Sŏnggye that ended the Goryeo dynasty.[26]

Etymology

The name "Goryeo" (고려; 高麗; Koryŏ), which is the source of the name "Korea", was originally used by Goguryeo (고구려; 高句麗; Koguryŏ) of the Three Kingdoms of Korea beginning in the early 5th century.[4] Other attested variants of the name have also been recorded as Gori (高離/槀離/稾離) and Guryeo (句麗). There have been various speculations for the breakdown of Goguryeo as a name, the most common being go meaning "high", "noble" and guri meaning "castle", related to the word gol used during medieval Goryeo meaning "place".{{Citation needed|date=January 2023} uccessor to Goguryeo and inherited its name.[4] Historically, Goguryeo (37 BC–668 AD), Later Goguryeo (901–918), and Goryeo (918–1392) all used the name "Goryeo".[4] Their historiographical names were implemented in the Samguk sagi in the 12th century.[27] Goryeo also used the names Samhan and Haedong, meaning "East of the Sea".[28]

History

Founding

In the late 7th century, the kingdom of Silla unified the Three Kingdoms of Korea and entered a period known in historiography as "Unified Silla" or "Later Silla". Later Silla implemented a national policy of integrating Baekje and Goguryeo refugees called the "Unification of the Samhan", referring to the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[31] Silla organized a new central army called the Ku-sŏdang (구서당; 九誓幢) that was divided into 3 units of Silla people, 3 units of Goguryeo people, 2 units of Baekje people, and 1 unit of Mohe people.[32] However, the Baekje and Goguryeo refugees retained their respective collective consciousnesses and maintained a deep-seated resentment and hostility toward Silla.[33] Later Silla was initially a period of peace, without a single foreign invasion for 200 years, and commerce, as it engaged in international trade from as distant as the Middle East and maintained maritime leadership in East Asia.[34][35][36] Beginning in the late 8th century, Later Silla was undermined by instability because of political turbulence in the capital and class rigidity in the bone-rank system, leading to the weakening of the central government and the rise of the "hojok" (호족; 豪族) regional lords.[37] The military officer Kyŏn Hwŏn revived Baekje in 892 with the descendants of the Baekje refugees, and the Buddhist monk Kung Ye revived Goguryeo in 901 with the descendants of the Goguryeo refugees;[33][38] these states are called Later Baekje and Later Goguryeo in historiography, and together with Later Silla form the Later Three Kingdoms.

Later Goguryeo originated in the northern regions of Later Silla, which, along with its capital located in modern-day Kaesong, North Korea, were the strongholds of the Goguryeo refugees.[39][40] Among the Goguryeo refugees was Wang Kŏn,[41] a member of a prominent maritime hojok based in Kaesong, who traced his ancestry to a great clan of Goguryeo.[42][43][44] Wang Kŏn entered military service under Kung Ye at the age of 19 in 896, before Later Goguryeo had been established, and over the years accumulated a series of victories over Later Baekje and gained the public's confidence. In particular, using his maritime abilities, he persistently attacked the coast of Later Baekje and occupied key points, including modern-day Naju.[45] Kung Ye was unstable and cruel: he moved the capital to Cheorwon in 905, changed the name of his kingdom to Majin in 904 then Taebong in 911, changed his era name multiple times, proclaimed himself the Maitreya Buddha, claimed to read minds, and executed numerous subordinates and family members out of paranoia.[46] In 918, Kung Ye was deposed by his own generals, and Wang Kŏn was raised to the throne. Wang Kŏn, who would posthumously be known by his temple name of Taejo or "Grand Progenitor", changed the name of his kingdom back to "Goryeo", adopted the era name of "Heaven's Mandate", and moved the capital back to his home of Kaesong.[45] Goryeo regarded itself as the successor to Goguryeo and laid claim to Manchuria as its rightful legacy.[3][44][47][48] One of Taejo's first decrees was to repopulate and defend the ancient Goguryeo capital of Pyongyang, which had been in ruins for a long time; afterward, he renamed it the "Western Capital", and before he died, he placed great importance on it in his Ten Injunctions to his descendants.[49][50]

Unification

In contrast to Kung Ye, who had harbored vengeful animosity toward Silla, Taejo (Wang Kŏn) was magnanimous toward the weakened kingdom. In 927, Kyŏn Hwŏn, who had vowed to avenge the last king of Baekje when he founded Later Baekje, sacked the capital of Later Silla, forced the king to commit suicide, and installed a puppet on the throne.[51] Taejo came to Later Silla's aid but suffered a major defeat at the hand of Kyŏn Hwŏn near modern-day Daegu; Taejo barely escaped with his life thanks to the self-sacrifices of Generals Sin Sung-gyŏm and Kim Nak, and, thereafter, Later Baekje became the dominant military power of the Later Three Kingdoms.[52] However, the balance of power shifted toward Goryeo with victories over Later Baekje in 930 and 934, and the peaceful annexation of Later Silla in 935. Taejo graciously accepted the capitulation of the last king of Silla and incorporated the ruling class of Later Silla.[52] In 935, Kyŏn Hwŏn was removed from his throne by his eldest son over a succession dispute and imprisoned at the temple Geumsansa, but he escaped to Goryeo three months later and was deferentially received by his former archrival.[53] In 936, upon Kyŏn Hwŏn's request, Taejo and Kyŏn Hwŏn conquered Later Baekje with an army of 87,500 soldiers, bringing an end to the Later Three Kingdoms period.[54][55] Goryeo proceeded to incorporate a major portion of the Balhae people whose links to Goguryeo were shared with Goryeo, accepting most of their royalty and nobility in their fold.

Following the destruction of Balhae by the Khitan Liao dynasty in 927, the last crown prince of Balhae and much of the ruling class sought refuge in Goryeo, where they were warmly welcomed and given land by Taejo. In addition, Taejo included the Balhae crown prince in the Goryeo royal family, unifying the two successor states of Goguryeo and, according to Korean historians, achieving a "true national unification" of Korea.[2][3] According to the Goryeosa jeolyo, the Balhae refugees who accompanied the crown prince numbered in the tens of thousands of households.[5] As descendants of Goguryeo, the Balhae people and the Goryeo dynasts were related.[56] Taejo felt a strong familial kinship with Balhae, calling it his "relative country" and "married country",[57] and protected the Balhae refugees.[47] This was in stark contrast to Later Silla, which had endured a hostile relationship with Balhae.[58] Taejo displayed strong animosity toward the Khitans who had destroyed Balhae. The Liao dynasty sent 30 envoys with 50 camels as a gift in 942, but Taejo exiled the envoys to an island and starved the camels under a bridge, in what is known as the "Manbu Bridge Incident".[59][60] Taejo proposed to Gaozu of Later Jin that they attack the Khitans in retribution for Balhae, according to the Zizhi Tongjian.[57] Furthermore, in his Ten Injunctions to his descendants, he stated that the Khitans are "savage beasts" and should be guarded against.[59][61]

Exodus en masse on part from the Balhae refugees would continue on at least until the early 12th century during the reign of King Yejong.[62][lower-alpha 1] Due to this constant massive influx of Balhae refugees, the Goguryeoic population in Goryeo is speculated to have become dominant[64][65][66][67] in proportion compared to their Silla and Baekje counterparts that have experienced devastating war and political strife[68][69][70] since the advent of the Later Three Kingdoms. By the end of the Later Three Kingdoms, territories populated by the original Silla people and considered that of "Silla proper" (原新羅) were reduced to Gyeongju and bits of the vicinity.[71] Later Baekje fared only little better than Later Silla before its fall in 936. Meanwhile, of the three capitals of Goryeo, two were Kaesong and Pyongyang which were initially populated by Goguryeoic settlers from the P'aesŏ Region (패서; 浿西) and Balhae.[72] Nonetheless, Goryeo proceeded to peacefully absorbing the ruling class of both countries and incorporated them under its bureaucracy; conducting political marriages and distributing positions according to their previous status in their respective countries.[73] In contrast to Silla's bone-rank system, these open policies implemented by Wang Kŏn enabled Goryeo to enjoy a larger pool of highly skilled bureaucrats and technicians with the addition of those coming from Silla and Baekje;[74] later on instilling a single agenda in terms of identity amongst its people. During the time of its existence, Goryeo also accepted a large amount of skilled workers from Medieval China and Tamna as well.[75][76][77]

Political reformation

Although Goryeo had unified the Korean Peninsula, the hojok regional lords remained quasi-independent within their walled domains and posed a threat to the monarchy. To secure political alliances, Taejo married 29 women from prominent hojok families, siring 25 sons and 9 daughters.[78] His fourth son, Gwangjong, came to power in 949 to become the fourth ruler of Goryeo and instituted reforms to consolidate monarchical authority. In 956, Gwangjong freed the prisoners of war and refugees who had been enslaved by the hojok during the tumultuous Later Three Kingdoms period, in effect decreasing the power and influence of the regional nobility and increasing the population liable for taxation by the central government.[48][79] In 958, advised by Shuang Ji, a naturalized Chinese official from the Later Zhou dynasty, Gwangjong implemented the kwagŏ civil service examinations, based primarily on the imperial examination of the Tang dynasty. This, too, was to consolidate monarchical authority. The kwagŏ remained an important institution in Korea until its abolition in 1894.[80] In contrast to Goryeo's traditional "dual royal/imperial structure under which the ruler was at once king, emperor and Son of Heaven", according to Remco E. Breuker, Gwangjong used a "full-blown imperial system".[81][82] All those who opposed or resisted his reforms were summarily purged.[83]

Gwangjong's successor, Gyeongjong, instituted the "Stipend Land Law" in 976 to support the new central government bureaucracy established on the foundation of Gwangjong's reforms.[84] The next ruler, Seongjong, secured centralization of government and laid the foundation for a centralized political order.[83] Seongjong filled the bureaucracy with new bureaucrats, who as products of the gwageo civil service examinations were educated to be loyal to the state, and dispatched centrally-appointed officials to administrate the provinces. As a result, the monarch controlled much of the decision making, and his signature was required to implement important decisions.[85] Seongjong supported Confucianism and, upon a proposal by the Confucian scholar Ch'oe Sŭng-no, the separation of government and religion.[83] In addition, Seongjong laid the foundation for Goryeo's educational system: he founded the Kukchagam national university in 992, supplementing the schools already established in Kaesong and Pyongyang by Taejo, and national libraries and archives in Kaesong and Pyongyang that contained tens of thousands of books.[86]

Goryeo–Khitan War

Following the "Manbu Bridge Incident" of 942, Goryeo prepared itself for a conflict with the Khitan Empire: Jeongjong established a military reserve force of 300,000 soldiers called the "Resplendent Army" in 947, and Gwangjong built fortresses north of the Chongchon River, expanding toward the Yalu River.[88][89] However an attempt to control the Yalu River basin in 984 failed due to conflict with the Jurchens.[60] The Khitans considered Goryeo a potential threat and, with tensions rising, invaded in 993.[90] The Jurchens warned Goryeo of the invasion twice. At first Goryeo did not believe the information but came around upon the second warning and took up a defensive strategy. The Koreans were defeated in their first encounter with the Khitans, but successfully halted their advance at Anyung-jin (in modern Anju, South Pyongan Province) at the Chongchon River.[60][91][92] Negotiations began between the Goryeo commander, Sŏ Hŭi, and the Liao commander, Xiao Sunning. In conclusion, Goryeo entered a nominal tributary relationship with Liao, severing relations with Song, and Liao recognized Goryeo sovereignty to the land east of the Yalu River. Goryeo was left free to deal with the Jurchens south of the Yalu and in 994–996, Sŏ Hŭi led an army into the area and built forts.[60][90] Afterward, Goryeo established the "Six Garrison Settlements East of the River" in its new territory.[60][89][93] In 994, Goryeo proposed to Song a joint military attack on Liao, but was declined;[94] previously, in 985, when Song had proposed a joint military attack on Liao, Goryeo had declined.[90] For a time, Goryeo and Liao enjoyed an amicable relationship.[60] In 996, Seongjong married a Liao princess.[95]

As the Khitan Empire expanded and became more powerful, it demanded that Goryeo cede the Six Garrison Settlements, but Goryeo refused.[96] In 1009, Kang Cho staged a coup d'état, assassinating Mokjong and installing Hyeonjong on the throne.[97] Goryeo sent an envoy to the Khitans telling them that the previous king had died and a new king had ascended the throne. In the following year, some Jurchen tribesmen who had been in conflict with Goryeo fled to the Khitans and told them of the coup. Under the pretext of avenging Mokjong, Emperor Shengzong of Liao led an invasion of Goryeo with an army of 400,000 soldiers.[60][98] Meanwhile, Goryeo tried to establish relations with Song but was ignored, as Song had agreed to the Chanyuan Treaty in 1005.[99] Goryeo gathered a 300,000 strong army under Kang Cho. In the first battle, the Goryeo forces led by Yang Kyu won a victory against the Liao. The Liao decided to split up their forces with one part heading south. The Goryeo army under the leadership of Kang Cho lost the second battle and suffered heavy casualties. The army was dispersed and many commanders were captured or killed, including Kang Cho himself.[60][100] Later, Pyongyang was successfully defended, but the Liao army marched toward Kaesong.[60]

Hyeonjong, upon the advice of Kang Kam-ch'an, evacuated south to Naju. Shortly afterward, the Liao won a pitched battle outside Kaesong and sacked the city.[60][100] He then sent Ha Kongjin (ko) and Ko Yŏnggi to sue for peace,[101] with a promise that he would pay homage in person to the Liao emperor. The Khitans, who were sustaining attacks from previously surrendered districts and the regrouped Korean army which disrupted their supply lines, accepted and began their withdrawal.[60][102][100] The Liao army became bogged down in the mountains during the winter and had to abandon much of their armour.[100] The Khitans were ceaselessly attacked during their withdrawal; Yang Kyu rescued from over 10,000 to over 30,000 prisoners of war, but died in battle.[103][60][104] According to the Goryeosa, due to continued attacks and heavy rain, the Khitan army was devastated and lost its weapons crossing the Yalu. They were attacked while crossing the Yalu River and many drowned.[103] Afterward, Hyeonjong did not fulfill his promise to pay homage in person to the Liao emperor, and when demanded to cede the Six Garrison Settlements, he refused.[60][100]

The Khitans built a bridge across the Yalu River in 1014 and attacked in 1015, 1016, and 1017:[100] victory went to the Koreans in 1015, the Khitans in 1016, and the Koreans in 1017.[105] Goryeo lost the Poju (Uiju) region. In 1018, Liao launched an invasion led by Xiao Paiya, the older brother of Xiao Sunning, with an army of 100,000 soldiers.[60][98] The Liao army tried to head straight for Kaesong. Goryeo gathered an army of 208,000 under Kang Kam-ch'an and ambushed and Liao army, which suffered heavy casualties. The Goryeo commander Kang Kam-ch'an had dammed a large tributary of the Yalu River and released the water on the unsuspecting Khitan soldiers, who were then charged by 12,000 elite cavalry.[60][106] The Liao army pushed on toward Kaesong under constant enemy harassment. After arriving within the vicinity of the well-defended capital, a contingent of 300 cavalry sent as scouts was annihilated, upon which the Liao army decided to withdraw.[60][107] The Liao troops soldiered on and headed toward the capital, but were met with stiff resistance and constant attacks, and were forced to retreat back north. During the retreat, 10,000 Liao army troops were annihilated by the Goryeo army under Kang Minch'ŏm (ko) of Goryeo. The retreating Liao army was intercepted by Kang Kam-ch'an in modern-day Kusong and suffered a major defeat, with only a few thousand soldiers escaping.[60][98][107]

Shengzong intended to invade again and amassed another large expeditionary army in 1019 but faced internal opposition. In 1020, Goryeo sent tribute and Liao accepted, thus resuming nominal tributary relations.[60][107] Shengzong did not demand that Hyeonjong pay homage in person or cede the Six Garrison Settlements.[98] The only peace treaty stipulations formalized in 1022 were a "declaration of vassalage" and the release of a detained Liao envoy. A Liao envoy was sent in the same year to formally invest the Goryeo king and upon his death in 1031, his successor Wang Hŭm was also invested as king by the Liao. After 1022, Goryeo did not have diplomatic relations with the Song until 1070, with the exception of an isolated embassy in 1030. The sole embassy was probably related to the rebellion of Balhae people in the Liao dynasty. The rebellion was quickly defeated by the Khitans, who returned to enforce Goryeo's tributary obligations. Goryeo adopted the reign title of the Liao in the fourth month of 1022.[99][107] The History of Liao claims that Hyeonjong "surrendered" and Shengzong "pardoned" him, but according to Hans Bielenstein, "[s]horn of its dynastic language, this means no more than that the two states concluded peace as equal partners (formalized in 1022)".[108] Bielenstein claims that Hyeonjong kept his reign title and maintained diplomatic relations with the Song dynasty.[108]

Kaesong was rebuilt, grander than before,[109] and, from 1033 to 1044, the Cheolli Jangseong, a wall stretching from the mouth of the Yalu River to the east coast of the Korean Peninsula, was built for defense against future invasions.[110] Liao never invaded Goryeo again.[98][111]

Golden age

Following the Goryeo–Khitan War, a balance of power was established in East Asia between Goryeo, Liao, and Song.[112][113] With its victory over Liao, Goryeo was confident in its military ability and no longer worried about a Khitan military threat.[114] Fu Bi, a grand councilor of the Song dynasty, had a high estimate of Goryeo's military ability and said that Liao was afraid of Goryeo.[115][116] Furthermore, regarding the attitude of the Koreans, he said: "Among the many tribes and peoples which, depending on their power of resistance, have been either assimilated or made tributary to the Khitan, the Koreans alone do not bow their heads."[117] Song regarded Goryeo as a potential military ally and maintained friendly relations as equal partners.[118] Meanwhile, Liao sought to build closer ties with Goryeo and prevent a Song–Goryeo military alliance by appealing to Goryeo's infatuation with Buddhism, and offered Liao Buddhist knowledge and artifacts to Goryeo.[119] During the 11th century, Goryeo was viewed as "the state that could give either the Song or Liao military ascendancy".[116] When imperial envoys, who represented the emperors of Liao and Song, went to Goryeo, they were received as peers, not suzerains.[120][121] Goryeo's international reputation was greatly enhanced.[118][122] Beginning in 1034, merchants from Song and envoys from various Jurchen tribes and the Tamna kingdom attended the annual Palgwanhoe in Kaesong, the largest national celebration in Goryeo;[122] the Song merchants attended as representatives of China while the Jurchen and Tamna envoys attended as members of Goryeo's tianxia.[123] During the reign of Munjong, the Heishui Mohe and Japan, among many others, attended as well.[124] The Tamna kingdom of Jeju Island was incorporated into Goryeo in 1105.[125]

Goryeo's golden age lasted about 100 years into the early 12th century and was a period of commercial, intellectual, and artistic achievement.[118] The capital was a center of trade and industry, and its merchants developed one of the earliest systems of double-entry bookkeeping in the world, called the sagae chi'bubŏp, that was used until 1920.[14][127] The Goryeosa records the arrival of merchants from Arabia in 1024, 1025, and 1040,[128] and hundreds of merchants from Song each year, beginning in the 1030s.[114] There were developments in printing and publishing, spreading the knowledge of philosophy, literature, religion, and science.[129] Goryeo prolifically published and imported books, and by the late 11th century, exported books to China; the Song dynasty transcribed thousands of Korean books.[130] The first Tripitaka Koreana, amounting to about 6,000 volumes, was completed in 1087.[131] The School of Nine Studies (ko) (구재학당; 九齋學堂; kujae haktang) was established in 1055 by Ch'oe Ch'ung, who is known as the "Haedong Confucius", and soon afterward there were 12 private academies in Goryeo that rivaled the Kukchagam national university.[132][133] In response, several Goryeo rulers reformed and revitalized the national education system, producing prominent scholars such as Kim Pusik.[134] In 1101, the Seojeokpo printing bureau was established at the Kukchagam.[132] In the early 12th century, local schools called hyanghak were established.[130] Goryeo's reverence for learning is attested to in the Gaoli tujing, or Goryeo dogyeong, a book by an envoy from the Song dynasty who visited Goryeo in 1123.[43][134] The reign of Munjong, from 1046 to 1083, was called a "Reign of Peace" (태평성대; 太平聖代) and is considered the most prosperous and peaceful period in Goryeo history. Munjong was highly praised and described as "benevolent" and "holy" (賢聖之君) in the Goryeosa.[135][136] In addition, he achieved the epitome of cultural blossoming in Goryeo.[121] Munjong had 13 sons: the three eldest succeeded him on the throne, and the fourth was the prominent Buddhist monk Uicheon.[137]

Goryeo was a period of great achievements in Korean art and culture, such as Koryŏ celadon, which was highly praised in the Song dynasty,[15][138] and the Tripitaka Koreana, which was described by UNESCO as "one of the most important and most complete corpus of Buddhist doctrinal texts in the world", with the original 81,258 engraved printing blocks still preserved at the temple Haeinsa.[139] In the early 13th century, Goryeo developed movable type made of metal to print books, 200 years before Johannes Gutenberg in Europe.[15][140][141]

Goryeo-Jurchen War

The Jurchens in the Yalu River region were tributaries of Goryeo since the reign of Taejo of Goryeo (r. 918–943), who called upon them during the wars of the Later Three Kingdoms period. Taejo relied heavily on a large Jurchen cavalry force to defeat Later Baekje. The Jurchens switched allegiances between Liao and Goryeo multiple times depending on which they deemed the most appropriate. The Liao and Goryeo competed to gain the allegiance of Jurchen settlers who effectively controlled much of the border area beyond Goryeo and Liao fortifications.[142] These Jurchens offered tribute but expected to be rewarded richly by the Goryeo court in return. However the Jurchens who offered tribute were often the same ones who raided Goryeo's borders. In one instance, the Goryeo court discovered that a Jurchen leader who had brought tribute had been behind the recent raids on their territory. The frontier was largely outside of direct control and lavish gifts were doled out as a means of controlling the Jurchens. Sometimes Jurchens submitted to Goryeo and were given citizenship.[143] Goryeo inhabitants were forbidden from trading with Jurchens.[144]

The tributary relations between Jurchens and Goryeo began to change under the reign of Jurchen leader Wuyashu (r. 1103–1113) of the Wanyan clan. The Wanyan clan was intimately aware of the Jurchens who had submitted to Goryeo and used their power to break the clans' allegiance to Goryeo, unifying the Jurchens. The resulting conflict between the two powers led to Goryeo's withdrawal from Jurchen territory and acknowledgment of Jurchen control over the contested region.[145][146][147]

As the geopolitical situation shifted, Goryeo unleashed a series of military campaigns in the early 12th century to regain control of its borderlands. Goryeo had already been in conflict with the Jurchens before. In 984, Goryeo failed to control the Yalu River basin due to conflict with the Jurchens.[60] In 1056, Goryeo repelled the Eastern Jurchens and afterward destroyed their stronghold of over 20 villages.[148] In 1080, Munjong of Goryeo led a force of 30,000 to conquer ten villages. However by the rise of the Wanyan clan, the quality of Goryeo's army had degraded and it mostly consisted of infantry. There were several clashes with the Jurchens, usually resulting in Jurchen victory with their mounted cavalrymen. In 1104, the Wanyan Jurchens reached Chongju while pursuing tribes resisting them. Goryeo sent Im Kan (임간; 林幹) to confront the Jurchens, but his untrained army was defeated, and the Jurchens took Chongju castle. Im Kan was dismissed from office and reinstated, dying as a civil servant in 1112. The war effort was taken up by Yun Kwan, but the situation was unfavorable and he returned after making peace.[149][150]

Yun Kwan believed that the loss was due to their inferior cavalry and proposed to the king that an elite force known as the Byeolmuban ("Special Warfare Army") be created. It existed apart from the main army and was made up of cavalry, infantry, and a Hangmagun ("Subdue Demon Corps"). In December 1107, Yun Kwan and O Yŏnch'ong set out with 170,000 soldiers to conquer the Jurchens. The army won against the Jurchens and built Nine Fortresses over a wide area on the frontier encompassing Jurchen tribal lands, and erected a monument to mark the boundary. However due to unceasing Jurchen attacks, diplomatic appeals, and court intrigue, the Nine Fortresses were handed back to the Jurchens. In 1108, Yun Kwan was removed from office and the Nine Fortresses were turned over to the Wanyan clan.[151][152][153] It is plausible that the Jurchens and Goryeo had some sort of implicit understanding where the Jurchens would cease their attacks while Goryeo took advantage of the conflict between the Jurchens and Khitans to gain territory. According to Breuker, Goryeo never really had control of the region occupied by the Nine Fortresses in the first place and maintaining hegemony would have meant a prolonged conflict with militarily superior Jurchen troops that would prove very costly. The Nine Fortresses were exchanged for Poju (Uiju), a region the Jurchens later contested when Goryeo hesitated to recognize them as their suzerain.[154]

Later, Wuyashu's younger brother Aguda founded the Jin dynasty (1115–1234). When the Jin was founded, the Jurchens called Goryeo their "parent country" or "father and mother" country. This was because it had traditionally been part of their system of tributary relations, its rhetoric, advanced culture, as well as the idea that it was "bastard offspring of Koryŏ".[155][156] The Jin also believed that they shared a common ancestry with the Balhae people in the Liao dynasty.[157] The Jin went on to conquer the Liao dynasty in 1125 and capture the Song capital of Kaifeng in 1127 (Jingkang incident). The Jin also put pressure on Goryeo and demanded that Goryeo become their subject. While many in Goryeo were against this, Yi Chagyŏm was in power at the time and judged peaceful relations with the Jin to be beneficial to his own political power. He accepted the Jin demands and in 1126, the king of Goryeo declared himself a Jin vassal (tributary).[158][159][160] However the Goryeo king retained his position as "Son of Heaven" within Goryeo. By incorporating Jurchen history into that of Goryeo and emphasizing the Jin emperors as bastard offspring of Goryeo, and placing the Jin within the template of a "northern dynasty", the imposition of Jin suzerainty became more acceptable.[161]

Power struggles

Template:Goryeo monarchs The Inju Yi clan married women to the kings from the time of Munjong to the 17th King, Injong. Eventually the Inju Yi clan gained more power than the monarch himself. This led to the coup of Yi Chagyŏm in 1126. It failed, but the power of the monarch was weakened; Goryeo underwent a civil war among the nobility.[162]

In 1135, Myoch'ŏng argued in favor of moving the capital to Sŏgyeong (now Pyongyang). This proposal divided the nobles. One faction, led by Myoch'ŏng, believed in moving the capital to Pyongyang and expanding into Manchuria. The other one, led by Kim Pusik (author of the Samguk sagi), wanted to keep the status quo. Myoch'ŏng failed to persuade the king; he rebelled and established the state of Taewi, but it failed and he was killed.[162]

Military regime

Although Goryeo was founded by the military, its authority was in decline. In 1014, a coup occurred but the effects of the rebellion did not last long, only making generals discontent with the current supremacy of the civilian officers.[163]

In addition, under the reign of King Uijong, military officers were prohibited from entering the Security Council, and even at times of state emergency, they were not allowed to assume commands.[164] After political chaos, Uijong started to enjoy traveling to local temples and studying sutra, while he was almost always accompanied by a large group of civilian officers. The military officers were largely ignored and were even mobilized to construct temples and ponds.[165]

Beginning in 1170, the government of Goryeo was de facto controlled by a succession of powerful families from the warrior class, most notably the Ch'oe family, in a military dictatorship akin to a shogunate.[166]

In 1170, a group of army officers led by Chŏng Chung-bu, Yi Ŭi-bang and Yi Ko launched a coup d'état and succeeded.[167] King Uijong went into exile and King Myeongjong was placed on the throne. Effective power, however, lay with a succession of generals who used an elite guard unit known as the Tobang to control the throne: military rule of Goryeo had begun. In 1179, the young general Kyŏng Taesŭng rose to power and began an attempt to restore the full power of the monarch and purge the corruption of the state.[168]

However, he died in 1183 and was succeeded by Yi Ŭimin, who came from a nobi (slave) background.[168][169] During this period, despite nearly three centuries of Goryeo rule, loyalty to the old Silla kingdom and Silla traditions remained latent in the Kyŏngju area. There were multiple rebellions by the Silla restoration movement to overthrow Goryeo's rule over the Sillan people.[170] Yi's unrestrained corruption and cruelty[169] led to a coup by general Ch'oe Ch'unghŏn,[171] who assassinated Yi Ŭimin and took supreme power in 1197.[167] For the next 61 years, the Ch'oe house ruled as military dictators, maintaining the Kings as puppet monarchs;[172] Ch'oe Ch'unghŏn was succeeded in turn by his son Ch'oe U, his grandson Ch'oe Hang[173] and his great-grandson Ch'oe Ŭi.[174]

When he took control, Ch'oe Ch'unghŏn forced Myeongjong off the throne and replaced him with King Sinjong.[175] What was different from former military leaders was the active involvement of scholars in Ch'oe's control, notably Prime Minister Yi Kyu-bo who was a Confucian scholar-official.[172]

After Sinjong died, Ch'oe forced his son to the throne as Huijong. After 7 years, Huijong led a revolt but failed. Then, Ch'oe found the pliable King Gojong instead.[175]

Although the House of Ch'oe established strong private individuals loyal to it, continuous invasion by the Mongols ravaged the whole land, resulting in a weakened defense ability, and also the power of the military regime waned.[171]

Mongol invasions and Yuan domination

Fleeing from the Mongols, in 1216 the Khitans invaded Goryeo and defeated the Korean armies multiple times, even reaching the gates of the capital and raiding deep into the south, but were defeated by Korean general Kim Ch'wiryŏ (김취려; 金就礪) who pushed them back north to Pyongan,[176][177] where the remaining Khitans were finished off by allied Mongol-Goryeo forces in 1219.[178][179]

Tension continued through the 12th century and into the 13th century, when the Mongol invasions started. After nearly 30 years of warfare, Goryeo swore allegiance to the Mongols, with the direct dynastic rule of Goryeo monarchy.[180]

In 1231, Mongols under Ögedei Khan invaded Goryeo following the aftermath of joint Goryeo-Mongol forces against the Khitans in 1219.[180] The royal court moved to Ganghwado in the Bay of Gyeonggi in 1232. The military ruler of the time, Ch'oe U, insisted on fighting back. Goryeo resisted for about 30 years but finally sued for peace in 1259.

Meanwhile, the Mongols began a campaign from 1231 to 1259 that ravaged parts of Gyeongsang and Jeolla. There were six major campaigns: 1231, 1232, 1235, 1238, 1247, 1253; between 1253 and 1258, the Mongols under Möngke Khan's general Jalairtai Qorchi launched four devastating invasions against Korea at tremendous cost to civilian lives throughout the Korean Peninsula.

Civilian resistance was strong, and the Imperial Court at Ganghwa attempted to strengthen its fortress. Korea won several victories but the Korean military could not withstand the waves of invasions. The repeated Mongol invasions caused havoc, loss of human lives and famine in Korea. In 1236, Gojong ordered the recreation of the Tripitaka Koreana, which was destroyed during the 1232 invasion. This collection of Buddhist scriptures took 15 years to carve on some 81,000 wooden blocks, and is preserved to this day.

In March 1258, the dictator Ch'oe Ŭi was assassinated by Kim Chun. Thus, dictatorship by his military group was ended, and the scholars who had insisted on peace with Mongolia gained power. Goryeo was never conquered by the Mongols, but exhausted after decades of fighting, Goryeo sent Crown Prince Wonjong to the Yuan capital to swear allegiance to the Mongols; Kublai Khan accepted, and married one of his daughters to the Korean crown prince.[181] Khubilai, who became khan of the Mongols and emperor of China in 1260, did not impose direct rule over most of Goryeo. Goryeo Korea, in contrast to Song China, was treated more like an Inner Asian power. The dynasty was allowed to survive,[182] and intermarriage with Mongols was encouraged, even with the Mongol imperial family, while the marriage between Chinese and Mongols was strictly forbidden when the Song dynasty was ended. Some military officials who refused to surrender formed the Sambyeolcho Rebellion and resisted in the islands off the southern shore of the Korean Peninsula.[183]

Late period

After 1270, Goryeo became a semi-autonomous client state of the Yuan dynasty. The Mongols and the Kingdom of Goryeo tied with marriages and Goryeo became khuda (marriage alliance) vassal of the Yuan dynasty for about 80 years and monarchs of Goryeo were mainly imperial sons in-law (khuregen). The two nations became intertwined for 80 years as all subsequent Korean kings married Mongol princesses,[181] and the last empress of the Yuan dynasty, Empress Gi, was a daughter of a Goryeo lower-ranked official;[184] Empress Gi was sent to Yuan as one of the many kongnyŏ (貢女; lit. 'tribute women', who were in effects slaves sent over as a sign of Goryeo submission to the Mongols)[184] and became empress in 1365.[185] Empress Gi had great political influence both the Yuan and the Goryeo court, and even manage to significantly increase the status and influence of her family members, including her father who was formally made into a king in the Yuan and her brother Ki Ch'ŏl who at some point manage to get more authority than the Goryeo king.[184] In 1356, King Gongmin purged the family of Empress Gi.[184] The kings of Goryeo held an important status like other important families of Mardin, the Uyghurs and Mongols (Oirats, Khongirad, and Ikeres).[186][187] It is claimed that one of Goryeo monarchs was the most beloved grandson of Kublai Khan.[188]

Last reform

When King Gongmin ascended to the throne, Goryeo was under the influence of the Mongol Yuan China. He was forced to spend many years at the Yuan court, being sent there in 1341 as a virtual prisoner before becoming king. He married the Mongol princess Princess Noguk (also known as Queen Indeok). But in the mid-14th century the Yuan was beginning to crumble, soon to be replaced by the Ming dynasty in 1368. King Gongmin began efforts to reform the Goryeo government and remove Mongolian influences.[189]

His first act was to remove all pro-Mongol aristocrats and military officers from their positions. Mongols had annexed the northern provinces of Goryeo after the invasions and incorporated them into their empire as the Ssangseong and Dongnyeong Prefectures. The Goryeo army retook these provinces partly thanks to defection from Yi Chach'un, a minor Korean official in service of Mongols in Ssangseong, and his son Yi Sŏnggye. In addition, Generals Yi Sŏnggye and Chi Yongsu (지용수; 池龍壽) led a campaign into Liaoyang.

After the death of Gongmin's wife Noguk in 1365, he fell into depression. In the end, he became indifferent to politics and entrusted that great task to the Buddhist monk Sin Ton. But after six years, Sin Ton lost his position. In 1374, Gongmin was killed by Hong Ryun (홍륜), Ch'oe Mansaeng (최만생), and others.

After his death, a high official Yi Inim assumed the helm of the government and enthroned eleven-year-old, King U, the son of King Gongmin.

During this tumultuous period, Goryeo momentarily conquered Liaoyang in 1356, repulsed two large invasions by the Red Turbans in 1359 and 1360, and defeated the final attempt by the Yuan to dominate Goryeo when General Ch'oe Yŏng defeated an invading Mongol tumen in 1364. During the 1380s, Goryeo turned its attention to the Wokou menace and used naval artillery created by Ch'oe Musŏn to annihilate hundreds of pirate ships.

Fall

In 1388, King U (son of King Gongmin and a concubine) and general Ch'oe Yŏng planned a campaign to invade now Liaoning of China. King U put the general Yi Sŏnggye (later Taejo) in charge, but he stopped at the border and rebelled.

Goryeo fell to Yi Sŏnggye, who put to death the last three Goryeo kings, usurped the throne, and established in 1392 the Joseon dynasty.

Government

[U]ntil 1270, when Koryŏ capitulated to the Mongols after thirty years of resistance, early Koryŏ rulers and most of its officials had held a "pluralist" (tawŏnjŏk) outlook that recognized greater and equal empires in China and in Manchuria, while positing Koryŏ as the center of a separate and bounded world ruled by the Koryŏ emperor, who claimed a ritual status reserved for the Son of Heaven.[190]

— Henry Em

Goryeo positioned itself at the center of its own "world" (천하; 天下) called "Haedong".[193] Haedong, meaning "East of the Sea", was a distinct and independent world that encompassed the historical domain of the "Samhan", another name for the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[193] The rulers of Goryeo, or Haedong, used the titles of emperor and Son of Heaven.[190] Imperial titles were used since the founding of Goryeo, and the last king of Silla addressed Wang Geon as the Son of Heaven when he capitulated.[194] Posthumously, temple names with the imperial characters of progenitor (조; 祖) and ancestor (종; 宗) were used.[190] Imperial designations and terminology were widely used, such as "empress", "imperial crown prince", "imperial edict", and "imperial palace".[190][194]

The rulers of Goryeo donned imperial yellow clothing, made sacrifices to Heaven, and invested sons as kings.[190] Goryeo used the Three Departments and Six Ministries imperial system of the Tang dynasty and had its own "microtributary system" that included Jurchen tribes outside its borders.[195][196] The military of Goryeo was organized into 5 armies, like an empire, as opposed to 3, like a kingdom.[190] Goryeo maintained multiple capitals: the main capital "Kaegyŏng" (also called "Hwangdo" or "Imperial Capital")[197] in modern-day Kaesong, the "Western Capital" in modern-day Pyongyang, the "Eastern Capital" in modern-day Gyeongju, and the "Southern Capital" in modern-day Seoul.[198] The main capital and main palace were designed and intended to be an imperial capital and imperial palace.[109][199] The secondary capitals represented the capitals of the Three Kingdoms of Korea.[200]

The Song, Liao, and Jin dynasties were all well informed of, and tolerated, Goryeo's imperial claims and practices.[201][119] According to Henry Em, "[a]t times Song reception rituals for Koryŏ envoys and Koryŏ reception rituals for imperial envoys from Song, Liao, and Jin suggested equal rather than hierarchical relations".[16] In 1270, Goryeo capitulated to the Mongols and became a semi-autonomous "son-in-law state" (부마국; 駙馬國) of the Yuan dynasty, bringing an end to its imperial system. The Yuan dynasty demoted the imperial titles of Goryeo and added "ch'ung" (충; 忠), meaning "loyalty", to the posthumous names of Goryeo kings, beginning with Chungnyeol. This continued until the mid-14th century, when Gongmin declared independence.[16]

Military

The military comprises both the army and the navy. Military leaders were appointed by Kings/Emperors.

Regional administration

Foreign relations

Goryeo affiliated itself with the successive short-lived Five Dynasties beginning with the Shatuo Later Tang dynasty in 933, and Taejo was acknowledged as the legitimate successor to Dongmyeong of Goguryeo.[193][56]

In 962, Goryeo entered relations with the nascent Song dynasty.[56] Song did not have real suzerainty over Goryeo, and Goryeo sent tribute mainly for the sake of trade.[202] Later, Goryeo entered nominal tributary relations with the Khitan Liao dynasty then the Jurchen Jin dynasty while maintaining trade and unofficial relations with the Song dynasty. The Korean missions to China were intended to seek knowledge on fields such as Confucianism, Buddhism, history, and other subjects, conduct diplomacy, and trade. Missions to the Song in 976, 986, and after 1105 stayed there for study. Goryeo requested texts from the Song in 991, 993, 1019, 1021, 1073, 1074, 1092, and after 1105. They also brought texts to China. Diplomatic missions were conducted to announce birthdays, deaths, and successions. Trade, in particular, was an important aspect of all the missions.[203] Annual tribute was expected to be exchanged for proper payment.[204] In 1093, Su Shi suggested that Goryeo envoys should stick to trade in commercial products such as silk and hair instead of books.[205] Sometimes missions were sent even though they would not be received to conduct trade.[206]

The Five Dynasties, Song dynasty, and Jin dynasty pretended that Goryeo was a tributary vassal. However this was a fiction. The Five Dynasties and the Song did not share a border with Goryeo and had no way to assert supremacy over it. The Liao invasions of Goryeo from 993 to 1020 were successfully repelled. The Jin made no similar effort against Goryeo.[94] Goryeo was not a vassal to these powers and successfully stood up to Liao and Jin through clever diplomacy and minimal appeasement. Goryeo was autonomous until Mongol rule.[204] Sinologist Hans Bielenstein described the nature of Goryeo's nominal tributary relations with the dynasties in China:

The Five Dynasties, Sung, Liao, and Chin all liked to pretend that Koryŏ was a tributary vassal. Nothing could be more wrong. The Five Dynasties and Sung had no common border with Koryŏ and no way, even if they had possessed the military resources, to assert any supremacy over it. The Liao invasions of Koryŏ from 993 to 1020 were successfully repelled by the Koreans. The Chin made no serious attempts against Koryŏ. The dynastic historians accepted nevertheless the official fiction and referred to Koryŏ by an unrealistic terminology.[94]

To repeat, Koryŏ was not a vassal with tributary duties to the Five Dynasties, Sung, Liao, and Chin. In spite of its smaller size, it was able to stand up to Liao and Chin, and did not have to buy peace. This required clever diplomacy and a minimum of appeasement. In spite of window-dressing, rhetorics, and even a pinch of nostalgia for the good old times of Korean-Chinese friendship, Koryŏ succeeded in keeping its autonomy until the advent of the Mongols.[204]

— Hans Bielenstein, Diplomacy and Trade in the Chinese World, 589–1276 (2005)

In 1270, Goryeo capitulated to the Yuan dynasty, which exercised a powerful influence over Goryeo affairs and the succession of Goryeo kings.[16] Goryeo remained under the Yuan dynasty until the mid-14th century.[16]

Goryeo used multiple calendars. In 938, it used the Later Jin calendar, in 948 Later Han, in 952 Later Zhou, in 963 Song, in 994 Liao, in 1016 Song, and in 1022 Liao. In 1136, Goryeo was presented with a Jin calendar. It is possible that Goryeo used different calendars simultaneously depending on which country they dealt with.[207]

| Year | Five Dynasties/Song | Khitans | Jurchens |

|---|---|---|---|

| 907–926 | 3 | 6 | |

| 927–946 | 11 | 2 | |

| 947–966 | 11 | ||

| 967–986 | 7 | ||

| 987–1006 | 11 | 14 | |

| 1007–1026 | 7 | 9 | |

| 1027–1046 | 1 | 10 | |

| 1047–1066 | 15 | ||

| 1067–1086 | 8 | 8 | |

| 1087–1106 | 7 | 11 | |

| 1107–1126 | 9 | 5 | 2 |

| 1127–1146 | 5 | 45 | |

| 1147–1166 | 2 | 43 | |

| 1167–1186 | 47 | ||

| 1187–1206 | 45 | ||

| 1207–1226 | 8 |

Society

Nobility

At the time of Goryeo, Korean nobility was divided into 6 classes.

- Kukkong (국공; 國公), duke of a nation

- Kun'gong (군공; 郡公), duke of a county

- Hyŏnhu (현후; 縣侯), marquis of a town

- Hyŏnbaek (현백; 縣伯), count of a town

- Kaegukja (개국자; 開國子) or hyŏnja (현자; 縣子), viscount of a town

- Hyŏnnam (현남; 縣男), baron of a town

Also the title t'aeja (태자; 太子) was given to sons of monarch. In most other east Asian countries this title meant crown prince. T'aeja was similar to taegun (대군; 大君) or gun (군; 君) of Joseon.

Religion

Buddhism

Buddhism in medieval Korea evolved in ways which rallied support for the state.[209]

Initially, the new Seon schools were regarded by the established doctrinal schools as radical and dangerous upstarts. Thus, the early founders of the various "nine mountain"[210] monasteries met with considerable resistance, repressed by the long influence in court of the Kyo schools. The struggles which ensued continued for most of the Goryeo period, but gradually the Seon argument for the possession of the true transmission of enlightenment would gain the upper hand.[210] The position that was generally adopted in the later Seon schools, due in large part to the efforts of Jinul, did not claim clear superiority of Seon meditational methods, but rather declared the intrinsic unity and similarities of the Seon and Kyo viewpoints.[211] Although all these schools are mentioned in historical records, toward the end of the dynasty, Seon became dominant in its effect on the government and society, and the production of noteworthy scholars and adepts. During the Goryeo period, Seon thoroughly became a "religion of the state," receiving extensive support and privileges through connections with the ruling family and powerful members of the court.[212] Although Buddhist predominated, Taoism was practiced in some temples, as was shamanism.[213]

Although most of the scholastic schools waned in activity and influence during this period of the growth of Seon, the Hwaeom school continued to be a lively source of scholarship well into the Goryeo, much of it continuing the legacy of Uisang and Wonhyo.[213] In particular the work of Kyunyŏ (均如; 923–973) prepared for the reconciliation of Hwaeom and Seon,[214] with Hwaeom's accommodating attitude toward the latter.[215] Gyunyeo's works are an important source for modern scholarship in identifying the distinctive nature of Korean Hwaeom.[215]

Another important advocate of Seon/Gyo unity was Ŭich'ŏn. Like most other early Goryeo monks, he began his studies in Buddhism with the Hwaeom school. He later traveled to China, and upon his return, actively promulgated the Cheontae (天台宗, or Tiantai in Chinese) teachings, which became recognized as another Seon school. This period thus came to be described as "five doctrinal and two meditational schools" (Ogyo Yangjong). Ŭich'ŏn himself, however, alienated too many Seon adherents, and he died at a relatively young age without seeing a Seon-Kyo unity accomplished.

The most important figure of Seon in the Goryeo was Jinul (知訥; 1158–1210). In his time, the sangha was in a crisis of external appearance and internal issues of doctrine. Buddhism had gradually become infected by secular tendencies and involvements, such as fortune-telling and the offering of prayers and rituals for success in secular endeavors. This kind of corruption resulted in the profusion of increasingly larger numbers of monks and nuns with questionable motivations. Therefore, the correction, revival, and improvement of the quality of Buddhism were prominent issues for Buddhist leaders of the period.

Jinul sought to establish a new movement within Korean Seon, which he called the "samādhi and prajñā society",[216] whose goal was to establish a new community of disciplined, pure-minded practitioners deep in the mountains.[211] He eventually accomplished this mission with the founding of the Seonggwangsa monastery at Mt. Jogye (曹溪山).[211] Jinul's works are characterized by a thorough analysis and reformulation of the methodologies of Seon study and practice. One major issue that had long fermented in Chinese Seon, and which received special focus from Jinul, was the relationship between "gradual" and "sudden" methods in practice and enlightenment. Drawing upon various Chinese treatments of this topic, most importantly those by Zongmi (780–841) and Dahui (大慧; 1089–1163),[217] Jinul created a "sudden enlightenment followed by gradual practice" dictum, which he outlined in a few relatively concise and accessible texts.[218] From Dahui, Jinul also incorporated the gwanhwa (觀話) method into his practice.[216] This form of meditation is the main method taught in Korean Seon today. Jinul's philosophical resolution of the Seon-Kyo conflict brought a deep and lasting effect on Korean Buddhism.

The general trend of Buddhism in the latter half of the Goryeo was a decline due to corruption, and the rise of strong anti-Buddhist political and philosophical sentiment.[219] However, this period of relative decadence would nevertheless produce some of Korea's most renowned Seon masters. Three important monks of this period who figured prominently in charting the future course of Korean Seon were contemporaries and friends: Gyeonghan Baeg'un (景閑白雲; 1298–1374), Taego Bou (太古普愚; 1301–1382) and Naong Hyegeun (懶翁慧勤; 1320–1376). All three went to Yuan China to learn the Linji (臨濟 or Imje in Korean) gwanhwa teaching that had been popularized by Jinul. All three returned, and established the sharp, confrontational methods of the Imje school in their own teaching. Each of the three was also said to have had hundreds of disciples, such that this new infusion into Korean Seon brought about considerable effect. Despite the Imje influence, which was generally considered to be anti-scholarly in nature, Gyeonghan and Naong, under the influence of Jinul and the traditional Tongbulgyo tendency, showed an unusual interest in scriptural study, as well as a strong understanding of confucianism and taoism, due to the increasing influence of Chinese philosophy as the foundation of official education. From this time, a marked tendency for Korean Buddhist monks to be "three teachings" exponents appeared.

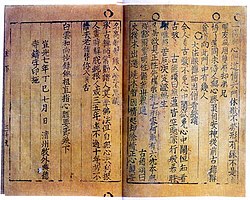

A significant historical event of the Goryeo period is the production of the first woodblock edition of the Tripitaka, called the Tripitaka Koreana. Two editions were made, the first one completed from 1210 to 1231, and the second one from 1214 to 1259. The first edition was destroyed in a fire, during an attack by Mongol invaders in 1232, but the second edition is still in existence at Haeinsa in Gyeongsang province. This edition of the Tripitaka was of high quality, and served as the standard version of the Tripitaka in East Asia for almost 700 years.[220]

Confucianism

Gwangjong created the national civil service examinations.[221] Seongjong was a key figure in establishing confucianism. He founded Kukchagam,[222] the highest educational institution of the Goryeo dynasty. This was facilitated by the establishment in 1398 of the Sungkyunkwan – an academy with a Confucian curriculum – and the building of an altar at the palace, where the king would worship his ancestors.

Islam

According to Goryeosa, Muslims arrived in the peninsula in the year 1024 in the Goryeo kingdom,[223] a group of some 100 Muslims, including Hasan Raza, came in September of the 15th year of Hyeonjong of Goryeo and another group of 100 Muslim merchants came the following year.

Trading relations between the Islamic world and the Korean peninsula continued with the succeeding Goryeo kingdom through to the 15th century. As a result, a number of Muslim traders from the Near East and Central Asia settled down in Korea and established families there. Some Muslim Hui people from China also appear to have lived in the Goryeo kingdom.[224]

With the Mongol armies came the so-called Saengmokin (Semu), or "colored-eye people", this group consisted of Muslims from Central Asia.[225] In the Mongol social order, the Saengmokin occupied a position just below the Mongols themselves, and exerted a great deal of influence within the Yuan dynasty.

It was during this period satirical poems were composed and one of them was the Sanghwajeom, the "Colored-eye people bakery", the song tells the tale of a Korean woman who goes to a Muslim bakery to buy some dumplings.[226]

Small-scale contact with predominantly Muslim peoples continued on and off. During the late Goryeo period, there were mosques in the capital Kaesong, called Ye-Kung, whose literary meaning is a "ceremonial hall".[228]

One of those Central Asian immigrants to Korea originally came to Korea as an aide to a Mongol princess who had been sent to marry King Chungnyeol of Goryeo. Goryeo documents say that his original name was Samga but, after he decided to make Korea his permanent home, the king bestowed on him the Korean name of Jang Sun-nyong.[229] Jang married a Korean and became the founding ancestor of the Deoksu Jang clan. His clan produced many high officials and respected Confucian scholars over the centuries. Twenty-five generations later, around 30,000 Koreans look back to Jang Sunnyong as the grandfather of their clan: the Jang clan, with its seat at Toksu village.[230]

The same is true of the descendants of another Central Asian who settled down in Korea. A Central Asian named Seol Son fled to Korea when the Red Turban Rebellion erupted near the end of the Mongol's Yuan dynasty.[231] He, too, married a Korean, originating a lineage called the Gyeongju Seol that claims at least 2,000 members in Korea.

Soju

Soju was first distilled around the 13th century, during the Mongol invasions of Korea. The Mongols had acquired the technique of distilling Arak from the Muslim world[232] during their invasion of Central Asia and the Middle East around 1256, it was subsequently introduced to Koreans and distilleries were set up around the city of Kaesong. Indeed, in the area surrounding Kaesong, Soju is known as Arak-ju (아락주).[233] Under the reign of King Chungnyeol, soju quickly became a popular drink, while the stationed region of Mongolian troops came to produce high-quality soju, for instance in Andong.[234]

Culture

Literature

The official histories of early Korea such as the Samguk sagi and Samguk yusa, written in Classical Chinese, remain some of the most important historical works in Korean historiography.[235][236][237]: 264

Various writing systems that utilized the phonetic value of Hanja characters were used to transcribe Old Korean, Idu being the most notable of them as it was used for administrative purposes and recordkeeping. This script originates in Goguryeo and was designed for a very specific sort of syntax that made use of postpositional particles, such as the Old Korean accusative marker *-ul/*-ur ending represented by 尸 'corpse' and 乙 '2nd Heavenly stem'. It was eventually phased out once it became too impractical upon the invention of Hangeul.[238]

Gugyeol was used to gloss Middle Chinese poems so Koreans could read them, with two versions having been used limited by their timeframes. Interpretative Gugyeol was predominant up to the 12th century and was supposed to tell the reader the meaning of the text and was meant to be read in Old Korean. The later form of Gugyeol appearing in the 13th century was meant to make it possible to spell out the Middle Chinese poem for the average reader, who would not know how Chinese sounded, by inferring the Koreanized pronunciation on it instead.[239]

Hyangga poetry, which made use of Hyangchal, another writing system used to write Old Korean, was contrary to common belief still widespread during Goryeo and a number of the surviving poems that were attributed to the Unified Silla period have been revealed to have been created during Goryeo. The Cheoyongga is one of these examples, a story about a man and his unfaithful wife.

The Goryeo aristocracy emphasized engaging with high literature and court poetry in Classical Chinese.[240] Learning Chinese poetry as well as composing poetry in Classical Chinese was a popular leisure activity for the aristocracy.[240]

Tripitaka Koreana

Tripitaka Koreana (팔만대장경) is a Korean collection of the Tripitaka of approximately 80,000 pages. The wooden blocks that were used to print it are stored in Haeinsa temple in South Gyeongsang Province. The second version was made in 1251 by Gojong in an attempt invoke the power of Buddhism to fend off the Mongol invasion. The wooden blocks are kept clean by leaving them to dry outside every year. The Tripiṭaka Koreana was designated a National Treasure of South Korea in 1962, and inscribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2007.[241][242]

Art

Goryeo celadon

The ceramics of Goryeo are considered by some to be the finest small-scale works of ceramics in Korean history. Key-fret, foliate designs, geometric or scrolling flowerhead bands, elliptical panels, stylized fish and insects, and the use of incised designs began at this time. Glazes were usually various shades of celadon, with browned glazes to almost black glazes being used for stoneware and storage. Celadon glazes could be rendered almost transparent to show black and white inlays.{{citation needed|date=February 2022}

Lacquerware with mother of pearl inlay

More info on Goryeo lacquerware

Construction techniques

These ceramics are of a hard porcellaneous body with porcelain stone as one of the key ingredients; however, it is not to be confused with porcelain. The body is low clay, quartz rich, high potassia and virtually identical in composition to the Chinese Yueh ceramics which scholars hypothesize occasioned the first production of celadon in Korea. The glaze is an ash glaze with iron colourant, fired in a reduction atmosphere in a modified Chinese-style 'dragon' kiln. The distinctive blue-grey-green of Korean celadon is caused by the iron content of the glaze with a minimum of titanium contaminant, which modifies the color to a greener cast, as can be seen in Chinese Yueh wares. However, the Goryeo potters took the glaze in a different direction than their Chinese forebears; instead of relying solely on underglaze incised designs, they eventually developed the sanggam technique of inlaying black (magnetite) and white (quartz) which created bold contrast with the glaze. Scholars also theorize that this developed in part to an inlay tradition in Korean metalworks and lacquer, and also to the dissatisfaction with the nearly invisible effect of incising when done under a thick celadon glaze.[243]

Modern celadon

Technology

It is generally accepted that the world's first metal movable type was invented in Goryeo during the 13th century by Ch'oe Yun-ŭi.[244][245][246][247][248][excessive citations] The first metal movable type book was the Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun that was printed in 1234. Technology in Korea took a big step in Goryeo and strong relation with the Song dynasty contributed to this. In the dynasty, Korean ceramics and paper, which come down to now, started to be manufactured.

See also

- List of monarchs of Korea

- Names of Korea

- Goryeo ware

Notes

References

Citations

- ↑ "Koryŏ dynasty | Korean history" (in en). Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Koryo-dynasty.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Kim 2012, p. 120.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Lee 1984, p. 103.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 "고려" (in ko). Korea Creative Contents Agency. http://www.culturecontent.com/content/contentView.do?search_div=CP_THE&search_div_id=CP_THE004&cp_code=rp0703&index_id=rp07032344&content_id=rp070313990001&search_left_menu=8.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/hm/view.do?treeId=010401&tabId=01&levelId=hm_045_0020. - ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 120–122.

- ↑ Seth, Michael (2019). A Concise History of Korea: From Antiquity to the Present. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 80.

- ↑ Lee, Soon Keun (2005). "On the Historical Succession of Goguryeo in Northeast Asia". Korea Journal 45 (1): 187–190. https://www.dbpia.co.kr/pdf/pdfView.do?nodeId=NODE09375791&googleIPSandBox=false&mark=0&useDate=&ipRange=false&accessgl=Y&language=ko_KR&hasTopBanner=true. Retrieved 9 February 2023.

- ↑ history net. "Goryeo Drives Back the Khitan" (in en). http://contents.history.go.kr/mobile/kh/view.do?tabId=02&category=english&levelId=kh_001_0040_0020_0010.

- ↑ Johnston, William M. (2013) (in en). Encyclopedia of Monasticism. Routledge. p. 275. ISBN 978-1-136-78715-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=WOZJAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA275.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 148.

- ↑ Till, Geoffrey; Bratton, Patrick (2012) (in en). Sea Power and the Asia-Pacific: The Triumph of Neptune?. Routledge. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-136-62724-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=RxOpAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA145. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ Lee 2017a, p. 52.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ronald, Ma (1997) (in en). Financial Reporting in the Pacific Asia Region. World Scientific. p. 239. ISBN 978-981-4497-62-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=-Q3tCgAAQBAJ&pg=PA239. Retrieved 8 February 2019.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Korea, 1000–1400 A.D.". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/07/eak.html.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Em 2013, p. 26.

- ↑ Oh, Kiseung (2021). "Disputes in Goryeo-Mongol border area and Reclaim of the Ssangseong-Prefectures at fifth year of King Kongmin regined". ̈숭실사학 46: 54. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002735397. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0024747. - ↑ Kim, Nak Jin (2017). "Goryeo's Conquest of the Jurchen and Tactical Systems of Byeolmuban during the Reign of Sukjong and Yejong". ͕한국학논총 47: 165. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002200455. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://www.okpedia.kr/Contents/ContentsView?contentsId=GC05308528&localCode=krcn&menuGbn=special. - ↑ Park, Jinhoon (2018). "On the Invasion of Red Turban Army (紅巾賊) in late Goryeo Dynasty and Military activities of Ahn-Woo (安祐)". Sahak Yonku: The Review of Korean History 130: 97–135. doi:10.31218/TRKH.2018.06.130.97. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002363239. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ↑ Lee, Jung Ran (2018). "Invasion by Red Turban Bandits in 1361 into Goryeo and King Gongmin's Politics of Evacuation in Chungcheong Region". 지방사와 지방문화 21: 40. https://www.kci.go.kr/kciportal/ci/sereArticleSearch/ciSereArtiView.kci?sereArticleSearchBean.artiId=ART002348729. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?cid=46621&docId=569009&categoryId=46621. - ↑ (in ko). https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?cid=46621&docId=534935&categoryId=46621.

- ↑ Lee 2017b.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). https://terms.naver.com/entry.naver?cid=62047&docId=918769&categoryId=62047. - ↑ 노태돈. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0003323. - ↑ Rawski 2015, pp. 198–200.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/ti/view.do?treeId=04013&levelId=ti_013_0010. - ↑ 노명호. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Index?contents_id=E0071025. - ↑ 이기환 (30 August 2017). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=201708300913001&code=960100&www. - ↑ 신형식 (1995). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0005839. - ↑ 33.0 33.1 Ro 2009, pp. 47–53.

- ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 99–101.

- ↑ Seth 2010, p. 66.

- ↑ Gernet, Jacques (1996) (in en). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. p. 291. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7. https://archive.org/details/historyofchinese00gern. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 112–115.

- ↑ 박한설. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0065743. - ↑ 이상각 (2014). "후삼국 시대의 개막" (in ko). 들녘. ISBN 979-11-5925-024-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=LonnCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT25. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ↑ "(2) 건국―호족들과의 제휴" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/nh/view.do?levelId=nh_011_0040_0030_0020_0020.

- ↑ 장덕호 (1 March 2015). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). https://news.joins.com/article/17253437. - ↑ 박종기 (2015). "고려 왕실의 뿌리 찾기" (in ko). 휴머니스트. ISBN 978-89-5862-902-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Qn6TCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT59. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/kc/main.do?levelId=kc_r200100. - ↑ 44.0 44.1 Ro 2009, pp. 72–83.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Kim 2012, p. 118.

- ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 117–118.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Rossabi 1983, p. 323.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 Grayson 2013, p. 79.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/hm/view.do?treeId=020104&tabId=01&levelId=hm_048_0010. - ↑ 이병도. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Index?contents_id=E0065813. - ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 116–117.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Kim 2012, p. 119.

- ↑ 고운기. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Naver. https://terms.naver.com/entry.nhn?docId=3568915&cid=59015&categoryId=59015. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/kc/main.do?levelId=kc_n100200. - ↑ 문수진; 김선주. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Index?contents_id=E0047180. - ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Rossabi 1983, p. 154.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 박종기 (2015). "신화와 전설에 담긴 고려 왕실의 역사" (in ko). 휴머니스트. ISBN 978-89-5862-902-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=Qn6TCgAAQBAJ&pg=PT66. Retrieved 13 March 2019.

- ↑ "Parhae | historical state, China and Korea" (in en). Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.. https://www.britannica.com/place/Parhae.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 이기환 (22 June 2015). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=201506221730411. - ↑ 60.00 60.01 60.02 60.03 60.04 60.05 60.06 60.07 60.08 60.09 60.10 60.11 60.12 60.13 60.14 60.15 60.16 60.17 60.18 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/kc/main.do?levelId=kc_i200300. - ↑ Lee 2010, p. 264.

- ↑ Jeon, Yeong-ho (2021). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". pp. 32–33. http://scholar.dkyobobook.co.kr/builderDownload.laf?barcode=4010028143027&artId=10576093&gb=view&rePdf=view. - ↑ 노태돈. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0050528. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%ED%9B%84%EC%82%BC%EA%B5%AD%ED%86%B5%EC%9D%BC&ridx=0&tot=575. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%ED%95%9C%EC%84%B1&ridx=1&tot=311. - ↑ Song, Young-Dae (2017). "Study on the Characteristics and Patterns of Balhae Descendants' Emigration to Goryeo From a Diasporic view". East Asian History 46: 137–172.

- ↑ Park, Soon Woo (2019). "An Examination of Settlements of Balhae Figures in Goryeo -Evidence of Balhae-style Roof-end Tiles Unearthed from Historic Sites of Goryeo-". Baeksan Hakbo (114): 97–120.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EA%B9%80%ED%97%8C%EC%B0%BD%EC%9D%98%20%EB%82%9C&ridx=0&tot=3. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%95%A0%EB%85%B8%EC%9D%98%20%EB%82%9C&ridx=0&tot=1. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%A0%81%EA%B3%A0%EC%A0%81&ridx=0&tot=1. - ↑ Kim, Bu-sik (1145). "Samguk-sagi, Book 12, Chapter "Silla", October of 935". http://db.history.go.kr/item/level.do?setId=8&totalCount=8&itemId=sg&synonym=off&chinessChar=on&page=1&pre_page=1&brokerPagingInfo=&position=2&levelId=sg_012r_0060_0260&searchKeywordType=BI&searchKeywordMethod=EQ&searchKeyword=935%EB%85%84&searchKeywordConjunction=AND.

- ↑ Kang, Ok-yeop. Ewha Womans University: 100. http://db.history.go.kr/download.do?levelId=kn_092_0040&fileName=kn_092_0040.pdf. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- ↑

Goryeosa, Book 2, 18th year of Taejo (January 8, 936):

"御天德殿, 會百僚曰, '朕與新羅, 歃血同盟, 庶幾兩國永好, 各保社稷. 今羅王固請稱臣, 卿等亦以爲可, 朕心雖愧, 衆意難違.' 乃受羅王庭見之禮, 群臣稱賀, 聲動宮掖. 於是, 拜金傅爲政丞, 位太子上, 歲給祿千碩, 創神鸞宮賜之. 其從者並收錄, 優賜田祿. 除新羅國爲慶州, 仍賜爲食邑."

English Translation:

"With his lieges assembled in the Cheondeok Palace, the King spoke out: For long have I vowed my devotion towards our alliance and friendship with Silla by painting my lips with blood as an oath to preserve our royal lines together. But since now the King of Silla requests to come under my fold as many deem right, it is hard to for me to cross the will of many despite my humbled and embarrassed heart."

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%9C%A1%EB%91%90%ED%92%88&ridx=0&tot=14. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%8C%8D%EA%B8%B0&ridx=0&tot=6. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/SearchNavi?keyword=%EC%B1%84%EC%9D%B8%EB%B2%94&ridx=0&tot=1. - ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0053416. - ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 122–123.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 124.

- ↑ Seth 2010, p. 82.

- ↑ Breuker 2010, p. 147.

- ↑ Breuker 2010, p. 136.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 Kim 2012, p. 125.

- ↑ Lee 1984, p. 105.

- ↑ Breuker 2010, p. 151.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 132.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/kc/main.do?levelId=kc_r200500. - ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 141–142.

- ↑ 89.0 89.1 Lee 1984, p. 125.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 90.2 Twitchett, Fairbank & Franke 1994, p. 103.

- ↑ 김남규. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Index?contents_id=E0034935. - ↑ Kim 2012, p. 142.

- ↑ 이용범. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Index?contents_id=E0001049. - ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 Bielenstein 2005, p. 182.

- ↑ Bielenstein 2005, p. 683.

- ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Bowman 2000, p. 203.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 98.2 98.3 98.4 Kim 2012, p. 143.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 Rogers 1961, p. 418.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 100.2 100.3 100.4 100.5 Twitchett, Fairbank & Franke 1994, p. 111.

- ↑ 하현강. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Index?contents_id=E0060537. - ↑ Yuk 2011, p. 35.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/nh/view.do?levelId=nh_015_0030_0030_0010_0010_0020. - ↑ 나각순. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Index?contents_id=E0035425. - ↑ Yuk 2011, pp. 38–39.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Korea Creative Content Agency. http://culturecontent.com/content/contentView.do?content_id=cp020813280001. - ↑ 107.0 107.1 107.2 107.3 Twitchett, Fairbank & Franke 1994, p. 112.

- ↑ 108.0 108.1 Bielenstein 2005, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ 109.0 109.1 Breuker 2010, p. 157.

- ↑ Kim 2012, p. 145.

- ↑ Yuk 2011, p. 14.

- ↑ Kim 2012, pp. 143–144.

- ↑ Rossabi 1983, p. 158.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Breuker 2010, p. 245.

- ↑ Rogers 1959, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ 116.0 116.1 Breuker 2010, p. 247.

- ↑ Rogers 1959, p. 19.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 Kim 2012, p. 144.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 Breuker 2003, p. 78.

- ↑ Breuker 2003, p. 60.

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 Breuker 2003, p. 79.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/hm/view.do?treeId=010402&tabId=01&levelId=hm_058_0060. - ↑ 강호선. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). National Institute of Korean History. http://contents.history.go.kr/front/km/view.do?levelId=km_011_0050_0030_0020. - ↑ Jung 2015, p. 192.

- ↑ Lee et al. 2014, p. 79.

- ↑ Chung 1998, pp. 236–237.

- ↑ 윤근호. "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}" (in ko). Academy of Korean Studies. http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr/Contents/Item/E0025356. - ↑ 정수일 (2002) (in ko). 창비. p. 335. ISBN 978-89-364-7077-7. https://books.google.com/books?id=H8kFjsJ9L_4C&pg=PA335. Retrieved 29 March 2019.