History:Morocco in World War II

This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (October 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

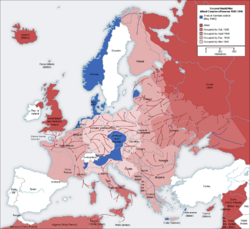

Morocco in World War II, in the Southern protectorate controlled by Vichy France, was part of the Axis powers from 1940 until 1942.[1] Following the landings of the Allied powers in North Africa, Morocco switched allegiances, and participated in Allied campaigns until the end of the war.[1]

Background

In 1940, after France became subject to the German occupation, France was divided into two parts.[2] One was occupied by German forces and the other was under French control, with its capital in Vichy.[2] The latter became the Vichy regime, which controlled Southern Morocco.[2] Post the 1942 landings, the Vichy administration remained but Southern Morocco was effectively under Allied control.[1] This Allied control saw many indigenous Moroccan soldiers fight on Allied behalf as part of French forces.[3] In Vichy controlled southern Morocco, the Moroccan Jewish population faced significant restrictions, due to the introduction of Vichy race laws.[4] This Allied control also made southern Morocco the location for the Casablanca Conference, where Churchill and Roosevelt met to discuss wartime operations.[5] On the southern Morocco home front, daily life changed little, but the nationalist movement attempted to gain momentum, despite facing opposition from French forces.[6] Northern Morocco was controlled by Spain through a "puppet" government headed by a viceroy and it participated largely in the Spanish Civil War, rather than World War II.[7]

Life during World War II

Slavery was a large part of life in Morocco, prior to and during the French protectorate and World War II, with many Moroccan households owning slaves.[8] Shantytowns arose near Moroccan cities in the 1930s and these continued to grow during the war.[9] European refugees fleeing to Morocco experienced poverty on their arrival in Morocco, with many refugees in Casablanca sleeping in converted dance halls, in terrible conditions.[10] In terms of education, separate educational institutions were set up to teach the Muslim Moroccan population and the French population.[11] Access to the baccalaureate; the degree necessary to gain university admission; was provided to the Moroccan Muslim population in 1930, but access to elite French schools (lycees) were not provided to the Muslim population until the end of the war in 1945.[11] Around ninety percent of the Muslim population of Morocco was illiterate during World War II.[4]

Persecution of Jews

In the lead up to the beginning of World War II, Jews in Morocco lived in significant poverty, in extremely crowded Jewish quarters called Mellahs.[4] Jews had little status in Morocco, with Resident General Charles Nogues not allowing Jews who enlisted in 1939 and 1940 to fight, but only to work on the industrial side of the war effort, in the factories and mines of France.[4] In 1940, laws were put in place by the Vichy administration which disallowed the majority of Jews from working as doctors, lawyers or teachers.[4] All Jews living in other neighbourhoods of Morocco were required to leave their houses and re-inhabit Mellahs.[4] Vichy anti-semitic propaganda was distributed throughout Morocco to encourage the boycotting of Jews. [4]Large amounts of pamphlets were pinned on the frontages of Jewish shops.[4] Around 7700 Jews, while attempting to flee Morocco in favour of America or Palestine, were moved to detention centres, with some refugees who were considered a threat to the Vichy regime being sent to Moroccan labour camps.[4] The American landings in 1942, were hoped by the Jews to mean the end of the Vichy laws, but General Nogues persuaded the Allies to allow for the continuation of French rule and Vichy laws, meaning the discrimination continued.[4]

Moroccan Nationalist movement

The Moroccan Nationalist movement gained momentum in Morocco in World War II.[6] Nationalists in Spanish Morocco created the 'National Reform Party' and the 'Moroccan Unity Movement', which united during WWII and were commonly vehicles for Fascist propaganda.[6] The 1942 landings were encouraged by the Nationalists in French Morocco, who hoped the Allies would assist in the fight for Moroccan independence.[6] After Moroccan Nationalists in French Morocco were found to have received letters from Ibrahim al- Wazzani, a nationalist in Spanish Morocco who was involved in aiding the Axis powers, the Allies rejected independence and upheld the Vichy laws.[6] On 11 January 1944, a group of Moroccan Nationalists, in French Morocco, created a declaration of Moroccan Independence which they proceeded to display to the French Resident General.[6] By 18 January 1944, the Moroccan Sultan and other influential figures had demonstrated their approval for the nationalists.[6] French authorities arrested the most influential nationalists linked to this document and took many to prison camps.[6] However, for many Moroccans, this only worked to increase support for the Nationalists.[6] The British secretly funded many Moroccan nationalist activities, in Southern and Northern Morocco, in an attempt to prevent German control of Morocco.[12]

Propaganda

The Germans, British and French all employed propaganda in Morocco in World War II.[13]From 1939, using Radio Berlin and Radio Stuttgart, Nazi Germany broadcast propaganda throughout Morocco.[13]This propaganda significantly promoted the German - Muslim relationship, whilst being largely anti-semitic.[13] From 1943, the Moroccan Bureau du Maghreb Arabe, created the journal 'al - maghrib al arabi' to disseminate Nazi Propaganda.[13] The British BBC began broadcasting news of the war to Morocco in 1939, presenting a pro- Britain outlook and broadcasts from Radio London attempted to present Britain as benevolent and so establish the support of Morocco's population.[13]In 1942, Moroccan dialects were introduced to the British broadcasts, in an attempt to successfully reach more people.[13]Propaganda was also used by the French in Morocco towards the indigenous Moroccan soldiers (goumiers).[13]Newspapers such as the Annasr attempted to establish a feeling of nationalism in the goumiers and many images were used in this propaganda to allow this propaganda to reach the illiterate soldiers.[13]

Moroccan Gourmiers

The Goumiers were the indigenous Moroccan soldiers who fought during World War II, initially fighting on behalf of France and the Axis powers.[3] The goumiers significantly numbered the army, with fifty three percent of the soldiers provided to France by its colonial empire in September of 1939 coming from North Africa.[3] After the Allied landing in Casablanca in 1942 (Operation Torch), the French administration in Morocco began to support the Allied powers.[1] The Moroccan goumiers began to be utilised by the Allies, mostly in mountain settings due to their effective mountaineering abilities.[3]The goumiers fought against German forces in Tunisia, successfully defeating the Germans in this area and taking over ten thousand prisoners of war.[3] Goumiers also participated in the Sicilian campaign (Operation Husky) and in the liberation of Corsica.[3] The German withdrawal from Corsica allowed the Allies control of its airfields, for use in subsequent campaigns against France and Italy.[3] The goumiers also successfully conquered the island of Elba, which was being used as a base for German aircraft and E- boats.[3] The goumiers also partook in 'Operation Diadem' where they aided in successfully infiltrating the Axis Gustav line which stretched across the Italian mountains[3]. Moreover, their fighting across the Aurunci mountains aided in allowing the Allied troops to break the Adolf Hitler Line and the taking of Route 6 by the Goumiers assisted in allowing the Allies to enter and liberate Rome.[3]In July, the goumiers went on to liberate Sienna from German control. [3]Ten thousand goumiers successfully liberated Marseilles from German control, driving the German troops to Vieux- Port, with General Schaeffer ordering his German troops to surrender the city in August of 1944.[3]

Military events

Operation Torch

Allied forces numbering around 90,000 entered Algeria and Morocco amphibiously on 8 November 1942.[14] In Morocco, the invasion took place through Casablanca and was designed to force the Vichy territories of North Africa into Allied hands.[15] The aim of Operation Torch was to gain North African territory to allow for movement East and control of the African coast.[3]Contrary to the Vichy regime, the Moroccan Sultan Sidi Mohammed Ben Youssef welcomed the Allied forces.[1]

Casablanca Conference

In January 1943, Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt, accompanied by their advisors, met secretly in a hotel in Casablanca to discuss the diplomatic and political issues currently at play and to decide the direction the Allied war strategy would be taking.[5]

References

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Baida, Jamaâ (2014-08-08). "The American landing in November 1942: a turning point in Morocco's contemporary history". The Journal of North African Studies 19 (4): 518–523. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.946825. ISSN 1362-9387. https://doi-org.ezproxy1.library.usyd.edu.au/10.1080/13629387.2014.946825.

- ↑ Jump up to: 2.0 2.1 2.2 Herausgeber., Michalczyk, John J., 1941-. Nazi law : from Nuremberg to Nuremberg. ISBN 9781350007239. OCLC 1024108321. http://worldcat.org/oclc/1024108321.

- ↑ Jump up to: 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Maghraoui, Driss (2014-08-08). "Thegoumiersin the Second World War: history and colonial representation" (in en). The Journal of North African Studies 19 (4): 571–586. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.948309. ISSN 1362-9387. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.948309.

- ↑ Jump up to: 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 4.8 4.9 Kenbib, Mohammed (2014-08-08). "Moroccan Jews and the Vichy regime, 1940–42" (in en). The Journal of North African Studies 19 (4): 540–553. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.950523. ISSN 1362-9387. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.950523.

- ↑ Jump up to: 5.0 5.1 Farrell, Brian P. (1993). "Symbol of Paradox: The Casablanca Conference, 1943". Canadian Journal of History 28 (1): 21–40. doi:10.3138/cjh.28.1.21. ISSN 0008-4107. http://dx.doi.org/10.3138/cjh.28.1.21.

- ↑ Jump up to: 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Cline, Walter B. (1947). "Nationalism in Morocco". Middle East Journal 1 (1): 18–28. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4321825.

- ↑ "Morocco - The Spanish Zone" (in en). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Morocco/The-Spanish-Zone.

- ↑ Goodman, R. D. (2013-08-21). "Expediency, Ambivalence, and Inaction: The French Protectorate and Domestic Slavery in Morocco, 1912-1956". Journal of Social History 47 (1): 101–131. doi:10.1093/jsh/sht053. ISSN 0022-4529. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jsh/sht053.

- ↑ "Morocco - Settlement patterns" (in en). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/place/Morocco/Settlement-patterns#ref846365.

- ↑ author., Hindley, Meredith,. Destination Casablanca : exile, espionage, and the battle for North Africa in World War II. ISBN 9781610394055. OCLC 999401044. http://worldcat.org/oclc/999401044.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Segalla, Spencer D. (2006). "French colonial education and elite Moroccan Muslim resistance, from the treaty of fes to the Berber Dahir". The Journal of North African Studies 11 (1): 85–106. doi:10.1080/13629380500409925. ISSN 1362-9387. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13629380500409925.

- ↑ Roslington, James (2014-08-08). "‘England is fighting us everywhere’: geopolitics and conspiracy thinking in wartime Morocco" (in en). The Journal of North African Studies 19 (4): 501–517. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.945715. ISSN 1362-9387. https://doi.org/10.1080/13629387.2014.945715.

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 13.6 13.7 Africa and World War II. Byfield, Judith A. (Judith Ann-Marie),, Brown, Carolyn A. (Carolyn Anderson), 1944-, Parsons, Timothy, 1962-, Sikainga, Ahmad Alawad,. New York. ISBN 9781107053205. OCLC 884305076. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/884305076.

- ↑ Walker, David A. (1987). "OSS and Operation Torch". Journal of Contemporary History 22 (4): 667–679. http://www.jstor.org/stable/260815.

- ↑ Middleton, Drew. "THE BATTLE FOR NORTH AFRICA" (in en). https://www.nytimes.com/1982/11/07/magazine/the-battle-for-north-africa.html.

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (October 2018) |