History:Primitive communism

| Part of a series on |

| Economic, applied, and development anthropology |

|---|

| Social and cultural anthropology |

| Part of a series on |

| Communism |

|---|

Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted or gathered are shared with all members of a group in accordance with individual needs. In political sociology and anthropology, it is also a concept (often credited to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels) that describes hunter-gatherer societies as traditionally being based on egalitarian social relations and common ownership.[1][2][3] A primary inspiration for both Marx and Engels were Lewis H. Morgan's descriptions of "communism in living" as practised by the Haudenosaunee of North America.[4] In Marx's model of socioeconomic structures, societies with primitive communism had no hierarchical social class structures or capital accumulation.[5]

Development of the idea

The original idea of primitive communism is rooted in idea of the noble savage present in the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau[6] and the early anthropology work of Morgan and Ely S. Parker.[7][8][9] Engels was the first to write about primitive communism in detail, with the 1884 publication of The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.[7][10] Engels categorised primitive communist societies into two phases: the "wild" (hunter-gatherer) phase that lacked permanent superstructure and had close relationships with the natural world, and the "barbarian" phase which held a superstructure like that of the ancient Germanic populations beyond the borders of the Roman Empire[8] and the Indigenous peoples of North America before colonisation by Europeans,[11] being intra-communally egalitarian and matrilineal within the community.[8]

Marx and Engels used the term more broadly than Marxists did later, and applied it not only to hunter-gatherers but also to some communities that engaged in subsistence agriculture.[12] There is also no agreement among later scholars, including Marxists, on the historical extent, or longevity, of primitive communism.[13] Marx and Engels also noted how capitalist accumulation latched itself onto social organizations of primitive communism.[14] For instance, in private correspondence the same year that The Origin of the Family was published, Engels attacked European colonialism, describing the Dutch regime in Java directly organizing agricultural production and profiting from it, "on the basis of the old communistic village communities".[clarification needed] He added that cases like the Dutch East Indies, British India and the Russian Empire showed "how today primitive communism furnishes ... the finest and broadest basis of exploitation".[15]

Anarchists, including Peter Kropotkin and Élisée Reclus, believed that societies that exemplified primitive communism were also examples of anarchist society before industrialisation.[16] An example of this is Kropotkin's anthropological work on anarchism and gift economies, Mutual Aid, which uses a study of the San people of southern Africa for its thesis.[17]

There was little development in the research of "primitive communism" among Marxist scholars beyond Engels' study until the 20th and 21st centuries when Ernest Mandel, Rosa Luxemburg,[18] Ian Hodder, Marija Gimbutas and others took up and developed upon the original theses.[19][20][21] Non-Marxist scholars of prehistory and early history did not take the term seriously, although it was occasionally engaged with and often dismissed.[22][23] The term primitive communism first appeared in Russian scholarship in the late 19th century, with references to primitive communism existing in ancient Crete.[24] However, it was not researched in any depth until the 20th century, with work such as that of the ethnographer Dmitry Konstantinovich Zelenin, who looked at non-hunter-gatherer societies within the Soviet Union to identify remnants of primitive communism within their societies.[25]

The belief of primitive communism as based on Morgan's work is flawed[8] due to Morgan's misunderstandings of Haudenosaunee society and his since-proven-wrong theory of social evolution.[26] Subsequent and more accurate research has focused on hunter-gatherer societies and aspects of such societies in relation to land ownership, communal ownership, and criminality and justice.[27] A newer definition of primitive communism could be summarized as societies that practice economic cooperation among the members of their community,[28][29] where almost every member of a community has their own contribution to society and land and natural resources are often shared peacefully among the community.[28][29]

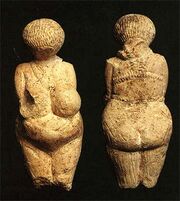

From the 20th century onward, sociologists and archaeologists have looked at the application of the term of primitive communism to hunter-gatherer societies of the paleolithic through to horticultural societies of the Chalcolithic,[30][31] including Paleo-American societies from the lithic stage through the archaic period.[32] Soviet archaeologists, influenced by Morgan's and Engels' works, interpreted the various paleolithic cultures that created Venus figures, many of which were found in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s, as evidence of the societies being primitive communist and matriarchal in nature.[33][34][35] The psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich concluded in 1931[36][37] the existence of an early communism from the information in Bronisław Malinowski's work.[38] However, Malinowski and the philosopher Erich Fromm did not consider this conclusion to be compelling.[39] Ernest Borneman supported Reich's ideas in his 1975 work Das Patriarchat.[40][41]

Primitive communist societies

Characteristics

In a primitive communist society, the productive forces would have consisted of all able-bodied persons engaged in obtaining food and resources from the land, and everyone would share in what was produced by hunting and gathering.[42] There would be no private property, which is distinguished from personal property[43] such as articles of clothing and similar personal items, because primitive society produced no surplus; what was produced was quickly consumed and this was because there existed no division of labour, hence people were forced to work together.[44] The few things that existed for any length of time - the means of production (tools and land), housing - were held communally. [45] In Engels' view, in association with matrilocal residence and matrilineal descent,[46] reproductive labour was shared.[47] There would have also been a lack of state.[48]

—John Scott and Gordon Marshall, 2007, Dictionary of Sociology.

Domestication of animals and plants following the Neolithic Revolution through herding and agriculture, and the subsequent urban revolution, were seen as the turning point from primitive communism to class society, as this transition was followed by the appearance of private ownership and slavery,[49] with the inequality that those entail.[37] In addition, parts of the population began to specialize in different activities, such as manufacturing, culture, philosophy, and science which lead in part to social stratification and the development of social classes.[50][51]

Egalitarian and communist-like hunter-gatherer societies have been studied and described by many well-known social anthropologists including James Woodburn,[52] Richard Borshay Lee,[53] Alan Barnard[54] and Jerome Lewis.[55][56] Anthropologists such as Christopher Boehm,[57] Chris Knight[58] and Lewis[59] offer theoretical accounts to explain how communistic, assertively egalitarian social arrangements might have emerged in the prehistoric past. Despite differences in emphasis, these and other anthropologists follow Engels in arguing that evolutionary change—resistance to primate-style sexual and political dominance—culminated eventually in a revolutionary transition. Lee criticizes the mainstream and dominant culture's long-time bias against the idea of primitive communism, deriding "Bourgeois ideology [that] would have us believe that primitive communism doesn't exist. In popular consciousness it is lumped with romanticism, exoticism: the noble savage."[53][60][61][62]

Papers have argued that the depiction of hunter-gatherers as egalitarian is misleading. According to one paper published in Current Anthropology, while levels of inequality were low, they were still present, with the average hunter-gatherer group having a Gini coefficient of 0.25 (for comparison, this was attained by the nation of Denmark in 2007).[63] This argument is in part supported by Alain Testart and others, who have said that a society without property is not free from problems of exploitation,[64] domination[65] or wars.[66] Marx and Engels, however, did not argue that communism brought about equality, as according to them equality was a concept without connection in physical reality.[67] Testart does support Engels' observations that societies without surplus are economically egalitarian and conversely that societies with surplus are unequal.[68][69][70]

Arnold Petersen has used the existence of primitive communism to argue against the idea that communism goes against human nature.[71] Hikmet Kıvılcımlı in his The Thesis of History argued that in pre-capitalist societies, the main dynamic of historical change "was not class struggle within society but rather the strong collective action" of egalitarian and collectivist values of "primitive socialist society".[72]

Example societies

Due to the strong evidence of an egalitarian society, lack of hierarchy, and lack of economic inequality, historian Murray Bookchin has argued that Çatalhöyük was an early example of anarcho-communism, and so an example of primitive communism in a proto-city.[73] However, still others use Çatalhöyük as an example that refutes the concept of primitive communism.[74] Similarly it has been argued that the Indus Valley civilisation is an example of a primitive communist society due to its perceived lack of conflict and social hierarchies.[75] Daniel Miller and others argue that such an assessment of the Indus Valley civilisation is not correct.[76][77]

The Marxist archaeologist V. Gordon Childe carried out excavations in Scotland from the 1920s and concluded that there was a neolithic classless society that reached as far as the Orkney Islands.[78][79] This has been supported by Perry Anderson, who has argued that primitive communism was prevalent in pre-Roman western Europe.[80] Descriptions of such societies are also present in the works of classical authors.[81][44]

Biblical scholars have also argued that the mode of production seen in early Hebrew society was a communitarian domestic one that was akin to primitive communism.[82][83] Claude Meillassoux has commented on how the mode of production seen in many primitive societies is a communistic domestic one.[84]

The Indian communist politician Shripad Amrit Dange considered ancient Indian society to be of a primitive communist nature.[85] Other communists within India have also labelled the societies of current indigenous groups, such as the Adivasi, as examples of primitive communism.[86] In Alfred Radcliffe-Brown's study of the Andamanese at the beginning of the 20th century he comments that they have "customs which result in an approach to communism" and "their domestic policy may be described as a communism".[87]

Alexander Mikhailovich Zolotarev (ru), in his 1960 work on the development of religious cult communities from tribal communities in the Balkans, spoke of the primitive communism of the "archaic form of the tribal system".[88]

Rolf Jensen in the 1980s conducted a historical study of Wolof society in west Africa looking at the development of class antagonisms from a primitive communist society.[89] Also in the 1980s, Bourgeault looked at the forceful transition of indigenous societies in Canada from their traditional structures, which were anarchist and communistic in nature, into capitalist exploitation due to encroaching imperialism and colonialism.[90][20][91] Such an area of interest has been a common topic of research for many fields beyond just Marxist scholars.[92] Some anthropologists, such as John H. Moore, have continued to argue that societies such as those of Native Americans constitute primitive communist societies, whilst acknowledging and incorporating the research showing the complexity and diversity in native American societies.[93][94]

James Connolly believed that "Gaelic primitive communism" existed in remnants in Irish society after it "had almost entirely disappeared" from much of western Europe.[95] The agrarian communes of the rundale system in Ireland have subsequently been assessed using a framework of primitive communism, where the system fits Marx and Engels' definition.[96]

Soviet theorists and anthropologists, such as Lev Sternberg, considered some of the indigenous groups of Siberia and the Russian far east (such as the Nivkh) to be primitive communist in nature.[97][98]

Criticism

Criticism of the idea of primitive communism relates to definitions of property, where anthropologists such as Margaret Mead argue that private property exists in hunter-gatherer and other "primitive societies" but provide examples that Marx and subsequent theorists label as personal property, not private property.[100][101] The idea has also been critiqued by other anthropologists for being based on Morgan's evolutionary model of society and for romanticising non‐Western societies.[102]

Western and non-Western Scholars have criticised applying models that are too ethnocentrically European to non-European societies.[103][44] Western scholars, including Leacock, have also criticised the ethnocentric point of view and biases in previous ethnographic research into hunter-gatherer societies.[84] This is similar to criticism of adhering to stadialism in analysing cultures.[104] Feminist scholars have criticised the idea of the lack of subjugation of women as suggested from the works of Engels,[84][7] while Marxist feminists have been critical of and have reassessed Engels' ideas and suggestions in The Origin of the Family related to the development of women's subjugation in the transition from primitive communism to class society.[105]

The Marxian economist Ernest Mandel criticised the research of Soviet scholars on primitive communism due to the influence of "Soviet-Marxist ideology" in their social sciences work.[44][106]

David Graeber and David Wengrow's The Dawn of Everything challenges the notion that humans ever lived in precarious, small scale societies with little or no surplus. While they provide examples of sharing egalitarian societies in pre-history they claim that a huge variety of complex societies (some with large cities) existed long before the supposed agricultural and then urban revolutions proposed by V. Gordon Childe.[74] Graeber and Wengrow's understanding of hunter-gatherer societies has, however, been questioned by other anthropologists.[107][108][109]

The use of the term "communism" to describe these societies has been questioned when put in comparison with a future post-industrial communism, particularly in relation to the difference in scale from small communal groups to the size of modern nation-states.[110][111]

Use of the term "primitive"

"Primitive" in recent anthropological and social studies has begun to fall out of use due to racial stereotypes surrounding the ideas of what is primitive. [112] Such a move has been supported by indigenous peoples who have faced racial stereotyping and violence due to being viewed as "primitive".[113][114] Due to this, the term "primitive communism" may be replaced by terms such as Pre-Marxist communism.[115]

Alain Testart and others have said that anthropologists should be careful when using research on current hunter-gatherer societies to determine the structure of societies in the paleolithic, where viewing current hunter-gatherer communities as "the most ancient of so-called primitive societies" is likely due to appearances and perceptions and does not reflect the progress and development that such societies have undergone in the past 10,000 years.[116]

There have been Marxist historians criticised for their comments on the "primitivism" and "barbarism" of societies prior to their contact with European empires, such as the comments of Endre Sík. Such views on "primitivism" and "barbarism" are also prevalent in the works of their non-Marxist contemporaries.[117][60][118] Marxist anthropologists have criticised and denounced Soviet anthropologists and historians for declaring indigenous communities they were studying for primitive communism as "degenerate".[44]

See also

Anthropology

- Classless society

- Ethnocentrism

- Functionalism (social sciences) (fr)

- Marxist anthropology (fr)

- Marxist archaeology

- Original affluent society

- Origins of society

- State of nature

- Structural functionalism

- Unilineal evolution

Economy

- Economic anthropology

- Economy of the Iroquois

- Potlatch

- Primitive accumulation of capital

- Right to property

- Social ownership

- The Gift (essay)

Law

- Great Law of Peace

- Indigenous rights

- Res communis

Marxism

References

- ↑ (in en) A Dictionary of Sociology. USA: Oxford University Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-860987-2.

- ↑ "Introductory Guide to Critical Theory - Modules on Marx: On the Stages of Economic Development" (in en). Purdue University. 1 January 2011. http://www.purdue.edu/guidetotheory/marxism/modules/marxstages.html.

- ↑ (in en) The Blackwell Dictionary of Political Science. Blackwell Publishers. August 1999. ISBN 978-0-631-20695-8.

- ↑ (in en) Houses and House-Life of the American Aborigines. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. 1881.

- ↑ (in en) Man the Hunter. Aldine Transaction. 1969. ISBN 978-0-202-33032-7.

- ↑ Woodcock, George, ed (1983). "Anarchism: A Historical Introduction" (in en). The Anarchist Reader (4 ed.). Fontana Paperbacks.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 (in en) The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State, in the Light of the Researches of Lewis H. Morgan. International Publishers. 1972. ISBN 978-0-7178-0359-0.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 (in fr) Le Communisme primitif n'est plus ce qu'il était. Collectif d'édition Smolny. 2009.

- ↑ (in en) A Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics and International Relations (4 ed.). Oxford University Press. 2018. ISBN 9780199670840.

- ↑ (in en) The Earth Shall Weep: A history of native America. New York: Grove Press. 2000.

- ↑ (in it) Storia Dell'Antropologia Culturale.

- ↑ Saito, Kohei, ed (2021). "Engels’s Legacy to Anthropology" (in en). Reexamining Engels's Legacy in the 21st Century. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 237–256. ISBN 978-3-030-55210-7.

- ↑ Casal (2020); Knight & June 2021; Seagle (1937); Kostick (2021)

- ↑ "On Race, Violence, and So-Called Primitive Accumulation" (in en). Social Text 34 (3): 27–50. September 2016. doi:10.1215/01642472-3607564. https://criticaltheory.berkeley.edu/wp-content/uploads/2017/10/Singh_On-Race-Violence-So-Called-Primitive-Accumulation_Social-Text.pdf.

- ↑ (in en) A Dictionary of Marxist Thought. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. 1991. pp. 174.

- ↑ Graham, Robert, ed (2005). "Elisee Reclus: Anarchy (1894)" (in en). Anarchism: A documentary history of libertarian ideas. 1. Black Rose Books.

- ↑ Hann, C.M., ed (17 December 1992). "Primitive communism and mutual aid, Kropotkin visits the Bushmen" (in en). Socialism: Ideals, Ideologies, and Local Practice. Routledge. ISBN 9780415083225.

- ↑ "Zachodni imperializm przeciwko pierwotnemu komunizmowi - nowe odczytanie pism ekonomicznych Róży Luksemburg" (in pl). Dziedzictwo Róży Luksemburg 6: 299–310. 1 January 2012. doi:10.14746/prt.2012.6.16.

- ↑ Reinisch, Dieter, ed (2012) (in de). Der Urkommunismus. Auf den Spuren der egalitären Gesellschaft. Vienna: Promedia. ISBN 978-3-85371-350-1.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Comunismo Primitivo e transição capitalista no pensamento de Rosa Luxemburgo" (in pt). Revista Direito e Práxis 8 (1). 2017. https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S2179-89662017000100262&script=sci_arttext.

- ↑ "Capital Accumulation and Debt Colonialism after Rosa Luxemburg." (in en). New Formations (Lawrence & Wishart Ltd.) 94 (94): 82–99. 2018. doi:10.3898/NEWF:94.06.2018.

- ↑ McGregor 2021.

- ↑ "Engels and the Origins of Human Society" (in en). International Socialism 2 (65). 1994. https://www.marxists.org/archive/harman/1983/xx/phil-rev.html.

- ↑ (in ru) Энциклопедический словарь Брокгауза и Ефрона: в 86 т. (82 т. и 4 доп.). Saint Petersburg. 1890–1907.

- ↑ "Имущественные запреты как пережитки первобытного коммунизма" (in ru). Transactions of the Institute of Anthropology and Ethnography (Leningrad) 1 (1). 1934.

- ↑ Morgan (1964); Service et al. (1981); Hersey (1993); Smith (2009); Haller Jr. (1971); Hume (2011); Yang (2012)

- ↑ Yang 2012.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 (in en) Cooperation, Community, and Co-Ops in a Global Era. Springer Science+Business Media. 2012. p. 40. ISBN 9781461458258. https://books.google.com/books?id=g5WTgR3mN2oC&pg=PA40.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Lee 1990.

- ↑ "Marxism, Prehistory, and Primitive Communism" (in en). Rethinking Marxism: A Journal of Economics, Culture & Society 1 (4): 145–168. 1988. doi:10.1080/08935698808657836. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08935698808657836.

- ↑ "Primitive communism: life before class and oppression" (in en). Socialist Worker. 28 May 2013. https://socialistworker.co.uk/art/33429/Primitive+communism%3A+life+before+class+and+oppression.

- ↑ (in en) The Cambridge history of the Native Peoples of the Americas. 1: North America, Part 1. Cambridge University Press. 1996.

- ↑ (in ru) Охотники, собиратели, рыболовы. Проблемы социально-экономических отношений в доземледельческом обществе. 1972.

- ↑ ""Первобытно-коммунистическое общество и его распад": доисторическое прошлое территории Беларуси согласно концепции В. К. Щербакова" (in ru). Journal of the Belarusian State University. History 4 (3). 2020. doi:10.33581/2520-6338-2020-3-54-63.

- ↑ (in de) Die Rede vom Matriarchat: Zur Gebrauchsgeschichte eines Arguments (Thesis). Zurich: Chronos. 2011. ISBN 978-3-0340-1067-2. http://www.research-projects.uzh.ch/p6758.htm.

- ↑ (in de) Der Einbruch der Sexualmoral. Zur Geschichte der sexuellen Ökonomie (2nd ed.). Berlin: International Psychoanalytic University. 1936. https://archive.org/details/EinbruchDerSexualmoral.ZurGeschichteDerSexuellenkonomie.2./page/n7/mode/2up.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Baxandall, Lee, ed (1972) (in en). SEX-POL: Essays 1929-1934. New York: Vintage Books New York. http://freudians.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/wilhelm-reich-sex-pol-essays-1929-1934.pdf.

- ↑ (in pl) Życie seksualne dzikich w północno-zachodniej Melanezji. 1929.

- ↑ "Rezension zu Wilhelm Reich "Der Einbruch der Sexualmoral"" (in de). Erich Fromm: Gesamtausgabe in zwölf Bänden. 8. Munich. 1999. pp. 93–96. ISBN 3421052808.

- ↑ (in de) Das Patriarchat. 1975.

- ↑ "Marxist Reappraisal of the Matriarchate" (in en). Current Anthropology 20: 341–359. 1979. doi:10.1086/202272.

- ↑ (in es) Diccionario de Economía Política. Madrid: Akal. 1975. ISBN 9788473390606.

- ↑ "Eight myths about socialism—and their answers" (in en). Party for Socialism and Liberation. http://www.pslweb.org/party/marxism-101/eight-myths-about-socialism.html.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 Diamond 1979.

- ↑ Ward Gailey (2016); Stearns et al. (2004); Svizzero & Tisdell (2016); Tomba (2012)

- ↑ "Early Human Kinship Was Matrilineal" (in en). Early Human Kinship. Oxford: Blackwell. 2008. pp. 61–82. http://www.chrisknight.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2007/09/Early-Human-Kinship-Was-Matrilineal.pdf.

- ↑ "The Digital Economy of the Sourdough: Housewifisation in the Time of COVID-19" (in en). tripleC (tripleC) 19 (1). 2021. https://triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/1222.

- ↑ "Primitive communism, barbarism and the origins of class society" (in en). Weekly Worker. 9 February 2012. https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/900/primitive-communism-barbarism-and-the-origins-of-c/.

- ↑ "The Revolutionary Theory of Karl Marx" (in en). Revolution: Theorists, Theories & Practice. University of Colorado, Boulder. 2020. https://spot.colorado.edu/~gyoung/home/Revolution.pdf.

- ↑ Stearns et al. 2004.

- ↑ (in en) Hunter-Gatherers (Foragers). 1 June 2020. https://hraf.yale.edu/ehc/summaries/hunter-gatherers.

- ↑ "Egalitarian Societies" (in en). Man 17 (3): 431–451. September 1982. doi:10.2307/2801707. https://archive.org/download/EgalitarianSocieties_805/1982-EgalitarianSocieties.pdf.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 "Demystifying Primitive Communism" (in en). Civilization in Crisis. Anthropological Perspectives. Gainesville, Florida: University of Florida Press. 1992. pp. 73–94.

- ↑ "Social origins: sharing, exchange, kinship" (in en). The Cradle of Language (Studies in the Evolution of Language 12). Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2008. pp. 219–35.

- ↑ "Ekila: "Blood, Bodies and Egalitarian Societies"" (in en). Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 14 (2): 297–315. 2008. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2008.00502.x. http://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/1317602/1/Ekila%20JRAI%202008%20Lewis%20version.pdf.

- ↑ Lewis, Jerome (2002). Forest Hunter-Gatherers and Their World: A Study of Mbendjele Yaka Pygmies of Congo-Brazzaville and Their Secular and Religious Activities and Representations (PDF) (PhD). London School of Economics and Political Science. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2021.

- ↑ (in en) Hierarchy in the Forest. The evolution of egalitarian behavior. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. 2001.

- ↑ Wray, Alison, ed (2002). "Language and revolutionary consciousness" (in en). The Transition to Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 138–160.

- ↑ "Vocal deception, laughter, and the linguistic significance of reverse dominance" (in en). The Social Origins of Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 2014.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 "The origins of women's oppression – a defence of Engels and a new departure" (in en). Marxist Left Review (16). 2018. https://marxistleftreview.org/articles/the-origins-of-womens-oppression-a-defence-of-engels-and-a-new-departure/.

- ↑ (in en) Limited Wants, Unlimited Means: A Reader on Hunter-Gatherer Economics and the Environment. St Louis: Island Press. 1998. p. 342. ISBN 155963555X.

- ↑ "'Communism in Living' - What can early human society teach us about the future?" (in en). Weekly Worker. 9 May 2018. https://weeklyworker.co.uk/worker/1110/communism-in-living/.

- ↑ "Wealth transmission and inequality among hunter-gatherers" (in en). Current Anthropology 51 (1): 19–34. 2010. doi:10.1086/648530. PMID 21151711.

- ↑ "Were Some more Equal than Others? II- Forms of Exploitation under Primitive Communism" (in en). Actuel Marx 58 (2): 144–158. 2015. doi:10.3917/amx.058.0144.

- ↑ (in fr) Critique du don: Etudes sur la circulation non marchande. Paris: Syllepse. 2007.

- ↑ (in en) War Before Civilization: the Myth of the Peaceful Savage. Oxford University Press. 1996.

- ↑ "Letters: Marx-Engels Correspondence 1875" (in en). https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1875/letters/75_03_18.htm.

- ↑ (in fr) Avant l'histoire: l'évolution des sociétés, de Lascaux à Carnac. Gallimard. 2012. ISBN 9782070131846.

- ↑ (in fr) Le communisme primitif: Tome I, Économie et Idéologie. Maison des Sciences de l'Homme. 1995. ISBN 978-2735101405.

- ↑ Dunayevskaya 2018.

- ↑ (in en) Socialism and Human Nature. Socialist Labor Party of America. November 2004. http://www.slp.org/pdf/others/h_nature_ap.pdf. Retrieved 21 March 2021.

- ↑ "Radical Approaches to Nation: An Introduction" (in en). Beyond Nationalism and the Nation-State: Radical Approaches to Nation. Routledge. 31 May 2021. ISBN 9780367684020.

- ↑ Bookchin (1987) (in en). The Rise of Urbanisation and Decline of Citizenship. pp. 18–22.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Kostick 2021.

- ↑ "The Essence of the Legacy of Mohenjo-daro" (in en). 18 February 2014. https://www.marxist.com/essence-of-the-legacy-of-mohenjo-daro.htm.

- ↑ "Ideology and the Harappan Civilzation" (in en). Journal of Anthropological Archaeology (4): 34–71. 1985. http://www.columbia.edu/itc/anthropology/v3922/pdfs/miller.pdf. Retrieved 2 February 2021.

- ↑ "Peaceful Harappans? Reviewing the evidence for the absence of warfare in the Indus Civilisation of north-west India and Pakistan (c. 2500-1900 BC)" (in en). Antiquity 79 (304): 411–423. 2005. doi:10.1017/S0003598X0011419X.

- ↑ (in en) Prehistoric Communities of the British Isles. London/Edinburgh: W. and R. Chambers. 1940.

- ↑ (in en) The Prehistory of Scotland. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., Ltd. 1935.

- ↑ (in en) Passages from Antiquity to Feudalism. Verso Books. 1996.

- ↑ "The problem of disappearance of hunter-gatherer societies in prehistory. Archaeological evidence and testimonies of classical authors" (in en). Listy filologické / Folia philologica (Centre for Classical Studies at the Institute of Philosophy of the Czech Academy of Sciences) 111 (3): 129–143. 1988.

- ↑ "Women First? On the Legacy of 'Primitive Communism'" (in en). Journal for the Study of the Old Testament 30 (1): 3–28. 2005. doi:10.1177/0309089205057775.

- ↑ (in en) Political Myth: On the Use and Abuse of Biblical Themes. Duke University Press. 2009.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 Mojab, Shahrzad, ed (12 March 2015) (in en). Marxism and Feminism. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781783603220.

- ↑ (in en) India from Primitive Communism to Slavery: A Marxist Study of Ancient History in Outline. 1949.

- ↑ "For an anthropological theory of praxis: dystopic utopia in Indian Maoism and the rise of the Hindu Right" (in en). Social Anthropology (Wiley) 29 (1): 68–86. February 2021. doi:10.1111/1469-8676.12978.

- ↑ (in en) The Andaman Islanders: a study in social anthropology. Cambridge University Press. 1922. https://archive.org/details/andamanislanders00radc/mode/2up.

- ↑ "On some geographical distribution of the Old Indo-European layer derivative roots" (in en). On Some Geographical Distribution of the Derivatives Roots of Old Indo-European Layer. 2020. https://www.academia.edu/44720956.

- ↑ "The Transition from Primitive Communism: The Wolof Social Formation of West Africa" (in en). The Journal of Economic History (Cambridge University Press) 42 (1): 69–76. March 1982. doi:10.1017/S0022050700026899. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2120497.

- ↑ "The Indian, the Métis and the Fur Trade Class, Sexism and Racism in the Transition from "Communism" to Capitalism" (in en). Studies in Political Economy: A Socialist Review 12 (1): 45–80. 1983. doi:10.1080/19187033.1983.11675649.

- ↑ "Marx and Anti-Colonialism" (in en). Leading Works in Law and Social Justice. Routledge. 23 March 2021.

- ↑ Pejnović, Vesna Stanković, ed (2021) (in en). Beyond Capitalism and Neoliberalism. Belgrade: Institute for Political Studies, Belgrade. ISBN 978-86-7419-337-2. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/350618018.

- ↑ "Free Goods and Primitive Communism: An Anthropological Perspective" (in en). Nature, Society, and Thought 20 (3–4): 418–424. 2007. https://conservancy.umn.edu/bitstream/handle/11299/150776/nst20n3-4a.pdf.

- ↑ Dunayevskaya 1982.

- ↑ "Connolly, the archive, and method" (in en). Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies 10 (1): 48–66. 2008. doi:10.1080/13698010801933853.

- ↑ "Marx on Primitive Communism: The Irish Rundale Agrarian Commune, its internal Dynamics and the Metabolic Rift" (in en). Irish Journal of Anthropology 12 (2). 2009. http://mural.maynoothuniversity.ie/2865/1/ES_Marx.pdf.

- ↑ "Primitive Communism and the Other Way Around" (in en). Socialist Realism without Shores. Duke University Press. 30 April 1997. ISBN 9780822398097.

- ↑ "The burdens of primitive communism" (in en). Anuário Antropológico 25 (1): 157–174. 8 February 2018. https://periodicos.unb.br/index.php/anuarioantropologico/article/view/6769.

- ↑ "Rereading the Indian in Benjamin West's "Death of General Wolfe"" (in en). American Art 9 (1): 75. 1995. doi:10.1086/424234.

- ↑ "Some Anthropological Considerations Concerning Natural Law" (in en). Natural Law Forum: 51–64. 1 January 1961. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/268214393.pdf.

- ↑ "Incorporeal Property in Primitive Society" (in en). The Yale Law Journal 37 (5): 551–563. March 1928. doi:10.2307/790747. https://www.jstor.org/stable/790747.

- ↑ "Communism" (in en). The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.. 5 September 2018. doi:10.1002/9781118924396. ISBN 9780470657225. https://pure.au.dk/ws/files/136724440/S_rensen_2018.pdf.

- ↑ "An Outline of a Revisionist Theory of Modernity" (in en). European Journal of Sociology (Cambridge University Press) 46 (3): 497–526. 2005. doi:10.1017/S0003975605000196. https://www.jstor.org/stable/23998994.

- ↑ "From ‘Materialism’ towards ‘Materialities’" (in en). Materialism and Politics. Berlin: ICI Berlin Press. 2021. https://repositorio.ul.pt/bitstream/10451/46651/1/bianchi-filion-donato-miguel-yuva_materialism--materialities.pdf.

- ↑ Vogel (2014); Dunayevskaya (1982); Dunayevskaya (2018); McGregor (2021)

- ↑ (in en) The Marxist Theory of the State. Pathfinder Press. October 1969. https://www.marxists.org/archive/mandel/1969/xx/state.htm.

- ↑ "Wrong About (Almost) Everything". Focaal. December 2021. https://www.focaalblog.com/2021/12/22/chris-knight-wrong-about-almost-everything//.

- ↑ "Gender egalitarianism made us human: patriarchy was too little, too late". Open Democracy. August 2018. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/gender-egalitarianism-made-us-human-patriarchy-was-too-little-too-late/.

- ↑ "On the Origin of Our Species". Literary Review. November 2021. https://literaryreview.co.uk/on-the-origin-of-our-species.

- ↑ "Primitive communism versus integral communism - Antagonism". 6 July 2009. https://libcom.org/library/primitive-communism-versus-integral-communism-antagonism.

- ↑ Casal 2020.

- ↑ Lee (1990); Corry (2009); Croom (2015); Ward Gailey (2016); Diamond (1979); Brown (2009)

- ↑ (in en) Sand Talk: How Indigenous Thinking Can Save the World. Melbourne: Text Publishing. 2020.

- ↑ "The Concepts of "Primitive" and "Native" in Anthropology" (in en). Yearbook of Anthropology (The University of Chicago Press on behalf of Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research): 187–202. 1955. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3031146. Retrieved 25 September 2021.

- ↑ (in en) Sandino's Communism: Spiritual Politics for the Twenty-First Century. Austin, Texas: University of Texas Press. 1992. ISBN 978-0-292-71647-6.

- ↑ "Some Major Problems in the Social Anthropology of Hunter-Gatherers [and Comments and Reply"] (in en). Current Anthropology (The University of Chicago Press) 29 (1): 1–31. February 1988. doi:10.1086/203612. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2743319.

- ↑ "Eurocentrism" (in en). A Cape of Asia: Essays on European History. Leiden University Press. 2011.

- ↑ "Claude Lévi-Strauss's Contribution to the Race Question: Race and History" (in en). American Anthropologist 121 (3): 721–724. September 2019. doi:10.1111/aman.13298.

Bibliography

- (in en) The Historiography of Communism. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. 2009. ISBN 9781592139224.

- "G. A. Cohen’s historical materialism: a feminist critique". Journal of Political Ideologies 25 (3): 316–333. 2020. doi:10.1080/13569317.2020.1773072.

- "Stephen Corry: Don't call these people primitive" (in en). The Guardian. 27 February 2009. https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/commentators/stephen-corry-don-t-call-these-people-primitive-1633333.html.

- "Slurs, stereotypes, and in-equality: a critical review of "How Epithets and Stereotypes are Racially Unequal"" (in en). Language Sciences 52: 139–154. 2015. doi:10.1016/j.langsci.2014.03.001. ISSN 0388-0001. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0388000114000151.

- Diamond, Stanley, ed (1979) (in en). Toward a Marxist Anthropology: Problems and Perspectives. New York: De Gruyter Mouton. doi:10.1515/9783110807714. ISBN 978-90-279-7780-9.

- (in en) Rosa Luxemburg, Women's Liberation, and Marx's Philosophy of Revolution. University of Illinois Press. 1982. ISBN 9780252018381.

- Dmitryev, Franklin, ed (2018). "Marx’s “New Humanism” and the Dialectics of Women’s Liberation in “Primitive” and Modern Societies". Marx's Philosophy of Revolution in Permanence for Our Day. Brill. pp. 241–256. ISBN 9789004383678.

- "Race and the Concept of Progress in Nineteenth Century American Ethnology" (in en). American Anthropologist 73 (3): 710–724. 1971. doi:10.1525/aa.1971.73.3.02a00120. https://anthrosource.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1525/aa.1971.73.3.02a00120.

- "Lewis Henry Morgan and the Anthropological Critique of Civilization" (in en). Dialectical Anthropology (Springer) 18 (1): 53–70. 1993. doi:10.1007/BF01301671. https://www.jstor.org/stable/29790527.

- "Evolutionisms: Lewis Henry Morgan, Time, and the Question of Sociocultural Evolutionary Theory" (in en). Histories of Anthropology Annual 7 (1): 91–126. January 2011. doi:10.1353/haa.2011.0009. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/236744114.

- "Did communism make us human?: On the anthropology of David Graeber". The Brooklyn Rail. June 2021. https://brooklynrail.org/2021/06/field-notes/Did-communism-make-us-human. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- "‘Primitive Communism’: Did it Ever Exist?" (in en). 10 November 2021. https://independentleft.ie/primitive-communism/.

- Upham, S., ed (1990). "Primitive communism and the origin of social inequality" (in en). Evolution of political systems: Sociopolitics in small-scale sedentary societies. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–246. ISBN 0521382521. https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/18020/1/TSpace0052.pdf.

- "Engels on women, the family, class and gender" (in en). Human Geography. 12 March 2021. doi:10.1177/19427786211000047.

- (in en) Ancient Society. Harvard University Press. 1964. ISBN 9780674865662.

- "Primitive Law and Professor Malinowski". American Anthropologist (Wiley) 39 (2): 275–290. April–June 1937. doi:10.1525/aa.1937.39.2.02a00080.

- "The Mind of Lewis H. Morgan" (in en). Current Anthropology 22 (1): 25–43. February 1981. doi:10.1086/202601. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2742415.

- "Lewis Henry Morgan" (in en). 2009. http://stsmith.faculty.anth.ucsb.edu/classes/anth3/courseware/History/Morgan.html.

- "The Neolithic Revolution and the Birth of Civilization" (in en). World Civilizations: The Global Experience. Pearson. 2004. ISBN 9780321164254. http://wps.ablongman.com/long_stearns_wc_4/0,8725,1123074-,00.html.

- "Economic evolution, diversity of societies and stages of economic development: A critique of theories applied to hunters and gatherers and their successors" (in en). Cogent Economics & Finance 4 (1). 2016. doi:10.1080/23322039.2016.1161322.

- (in en) Marx's Temporalities. Brill. 9 November 2012. ISBN 978-90-04-23679-0.

- (in en) Marxism and the Oppression of Women. Chicago: Haymarket Books. March 2014. ISBN 9781608463404.

- "Locating primitive communism in capitalist social formations" (in en). Dialectical Anthropology 40 (3): 259–266. September 2016. doi:10.1007/s10624-016-9431-8.

- "Specter of the commons: Karl Marx, Lewis Henry Morgan, and nineteenth-century European stadialism" (in en). Borderlands (Gale Academic OneFile) 11 (2). September 2012.

Further reading

Historic and original texts

- (in French) Paul Lafargue, La propriété, Origine et évolution, Éditions du Sandre, 2007 (1890) (Read online, Marxist Internet Archive)

- Paul Lafargue, The Evolution of Property from Savagery to Civilization, (1891), (new edition, 1905)

- (in French) Paul Lafargue, Le Déterminisme économique de Karl Marx. Recherche sur l'origine des idées de Justice, du Bien, de l'âme et de dieu, L'Harmattan, 1997 (1909)

- (in German) Heinrich Eildermann (de): Urkommunismus und Urreligion: Geschichtsmaterialistisch beleuchtet. Nabu, 2011, ISBN 978-1245831512 (reprint from 1921; Full text on archive.org).

- (in German) Karl August Wittfogel: Vom Urkommunismus bis zur proletarischen Revolution. Eine Skizze der Entwicklung der menschlichen Gesellschaft. Part 1: Urkommunismus und Feudalismus. Junge Garde, Berlin 1922.

- (in Hungarian) István Kertész (historian) (hu) Az ősközösség kora és az ókori-keleti társadalmak, IKVA Kiadó, Budapest, 1990

- Johann Jakob Bachofen, Myth, Religion, and Mother Right: Selected Writings of J.J. Bachofen by Joseph Campbell (Introduction) and George Boas (preface), Princeton University Press, 380p., 1992

Other texts

- Marx, Engels, Luxemburg and the Return to Primitive Communism

- Primitive Communism, Barbarism and the Origins of Class Society by Lionel Sims

- Hunter-Gatherers and the Mythology of the Market by John Gowdy