Huaya

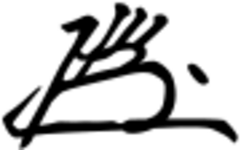

Huaya ("flower seal"; Chinese: 花押; pinyin: Huā Yā; Korean: 화압, romanized: Hwaap; Japanese: 花押, romanized: Kaō, Vietnamese: Template:Langr, chữ Hán: 花押) are stylized signatures or marks used in East Asian cultures in place of a fully written signature. Originating from China, the huaya was historically used by prominent figures such as government officials, monks, artists, and craftsmen. The use of stamp seals gradually replaced the huaya, though they are still used occasionally in modern times by important people.

Design

Most huaya are constructed from parts of Chinese characters and resemble them to a certain degree. A small number of early marks, mostly used by Buddhist monks, are simply abstract pictures related to the person's identity.

Generally, one or more of the characters from the person's name is used in creating a huaya. Designs are often taken from highly calligraphic, distorted, or alternative forms of a character, as well as merging parts of two characters into a single mark (similar to a monogram). Descendants of the same family or artistic lineage will often have similar-looking marks.

Several styles of huaya have existed throughout history. Early marks from the Tang (618-907) and Song dynasties (960–1279) were more abstract and minimalistic compared to later designs. During the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), marks with a design between two horizontal lines became popular in China, and was adopted later by the Tokugawa clan in Japan.

History

China

The oldest surviving record of huaya is in the Book of Northern Qi, the official history of the Northern Qi dynasty (550–577 AD).[1] Huaya reached its peak popularity during the Northern Song dynasty (960-1127).[2] After that, its popularity began to decline.

-

Mark of Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (685-762)

-

Mark of Emperor Taizu of Song (927-976)

-

Mark of Emperor Taizong of Song (939–997)

-

Mark of Emperor Huizong of Song (1082-1135)

-

Mark of the Hongwu Emperor (1328-1398)

-

Mark of the Chongzhen Emperor (1611-1644)

-

Mark of the painter Bada Shanren (1626–1705)

-

Mark of general Li Hongzhang (1823-1901)

Japan

Huaya first spread to Japan during the Heian period (794-1185), where it is called Kaō.[3] Though their use became far less widespread after the Edo period, they continue to be used even by some contemporary politicians and other famous people.[4] The reading and identification of individual kaō often requires specialist knowledge; whole books devoted to the topic have been published.[5]

-

Mark of Taira no Tadamori (1096–1153)

-

Mark of shogun Ashikaga Takauji (1305-1358)

-

Mark of Emperor Go-Hanazono (1418-1471)

-

Mark of shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1543-1616)

-

Mark of prime minister Hideki Tojo (1884-1948)

-

Marks of members of the Council of Five Elders

Vietnam

Huaya spread to Vietnam after Vietnamese independence from China. It was referred to as Template:Langr. It was widely used during the Lê dynasty with both the Nguyễn and Trịnh lords using their own Template:Langr.[6] These Template:Langr are seen in letters to Japan and other nations.

-

The Template:Langr on a 1635 letter to Japan.

-

The Template:Langr on a 1684 letter to Japan.

-

This Template:Langr "曉示 hiểu thị" is from a 1606 letter by Nguyễn Hoàng 阮潢 to Tokugawa Ieyasu 徳川家康.

-

Mark of Nguyễn Hoàng (阮潢; 1525-1613) seen on a copy of a letter from Japan.

-

A Template:Langr seen on a letter from Phúc Nghĩa Hầu (福義侯) to the “King of Japan”.

See also

- Tughra, stylised Arabic signatures used by Ottoman sultans

- Khelrtva, stylised Georgian calligraphic signatures

- Monogram

- Seals in the Sinosphere

- Signature

References

- ↑ 李百药 (November 2020), 北齐书, 中国社会科学出版社, ISBN 978-7-5203-7496-5

- ↑ "日本的"花押"到底是什么?". June 6, 2020. https://zhuanlan.zhihu.com/p/146027372.

- ↑ 望月 鶴川 [Kakusen Mochizuki] (June 2005), 朝陽会 [Chōyōkai], ISBN 978-4-903059-03-7

- ↑ 佐藤 進一 [Satō Shin'ichi] (September 2000), 平凡社 [Heibonsha], ISBN 978-4-582-76367-6

- ↑ 上島 有 [Tamotsu Kamishima] (December 2004), 山川出版社 [Yamakawa Shuppansha], JPNO 20717189, ISBN 978-4-634-52330-2

- ↑ Võ, Vinh Quang; Hồ, Xuân Thiên; Hồ, Xuân Diên (29 June 2018). "Họ Hồ làng Nguyệt Biều - Hương Cần và dấu ấn của Đức Xuyên tử Hồ Quang Đại với lịch sử xã hội xứ Thần Kinh". http://tapchisonghuong.com.vn/tin-tuc/p2/c15/n26823/Ho-Ho-lang-Nguyet-Bieu-Huong-Can-va-dau-an-cua-Duc-Xuyen-tu-Ho-Quang-Dai-voi-lich-su-xa-hoi-xu-Than-Kinh.html.

|