Kerner's breakdown minimization principle

Kerner’s breakdown minimization principle (BM principle) is a principle for the optimization of vehicular traffic networks introduced by Boris Kerner in 2011.[1]

Definition

The BM principle states that the optimum of a traffic network with N network bottlenecks is reached when dynamic traffic optimization and/or control are performed in the network in such a way that the probability for spontaneous occurrence of traffic breakdown in at least one of the network bottlenecks during a given observation time reaches the minimum possible value. The BM principle is equivalent to the maximization of the probability that traffic breakdown occurs at none of the network bottlenecks.

Empirical ground

The empirical ground for Kerner’s BM principle is the set of fundamental empirical features of traffic breakdown at a highway bottleneck found in measured traffic data:

- Traffic breakdown at a highway bottleneck is a local phase transition from free flow (F) to congested traffic whose downstream front is usually fixed at the bottleneck location. Within this front, vehicles accelerate from congested traffic to free flow downstream of the bottleneck.

- At the same bottleneck, traffic breakdown can be either spontaneous (Figure 1(a)) or induced (Figure 1 (b)).

- The probability of traffic breakdown is an increasing flow rate function.

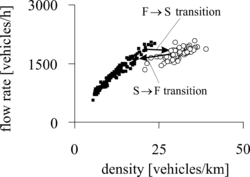

- There is a well-known hysteresis phenomenon associated with traffic breakdown: When the breakdown has occurred at some flow rates with resulting congested pattern formation upstream of the bottleneck, then a return transition to free flow at the bottleneck is usually observed at considerably smaller flow rates (Figure 2).

A spontaneous traffic breakdown occurs, where there are free flows both upstream and downstream of the bottleneck before the breakdown has occurred (Fig. 1(a)). In contrast, an induced traffic breakdown is caused by a propagation of a congested pattern that has earlier emerged for example at another downstream bottleneck (Figure 1 (b)).

The set 1–4 of the fundamental empirical features of traffic breakdown at a highway bottleneck has first been explained in Kerner’s three-phase theory (Figure 3). In Kerner’s theory there are three phases: Free flow (F), synchronized flow (S), wide moving jam (J). Synchronized flow and wide moving jam are associated with congested traffic. The synchronized flow phase is defined as congested traffic whose downstream front is fixed at the bottleneck. Therefore, in accordance with empirical feature 1 traffic breakdown is a phase transition from free flow to synchronized flow (called F → S transition). The main feature of an F → S transition is as follows (Figure 3 (c, d)): There is a broad range of flow rates on a link of the traffic network between the minimum and maximum capacities of free flow. Within this range of flow rates traffic breakdown occurs with some probability, which depends on the flow rate (Figure 3 (c)).

Mathematical formulation

Assuming that at different bottlenecks traffic breakdown occurs independently, the probability for spontaneous occurrence of traffic breakdown in at least one of the network bottlenecks during a given observation time can be written as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ P_\mathrm{net}=1-\prod^N_{k=1}(1-P^{(B,k)}) }[/math]

In accordance with the BM principle, the network optimum is reached at

- [math]\displaystyle{ \min_{q_1,q_2,\ldots,q_M}\{P_\mathrm{net}( q_1,q_2,\ldots,q_M)\} }[/math]

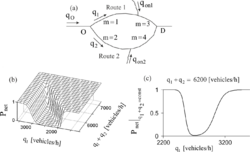

Here, [math]\displaystyle{ M }[/math] is the number of network links for which flow rates can be adjusted; [math]\displaystyle{ q_{m} }[/math] is the link inflow rate for a link with index [math]\displaystyle{ m }[/math]; [math]\displaystyle{ m=1,2,\ldots,M }[/math], where [math]\displaystyle{ M\gt 1 }[/math]; [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math] is the bottleneck index, [math]\displaystyle{ k=1,2,\ldots,N }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ N\gt 1 }[/math]; [math]\displaystyle{ P^{(B,k)} }[/math] is the probability that during the observation time interval traffic breakdown occurs at bottleneck with index [math]\displaystyle{ k }[/math].

Simulations

Results of simulations of the BM principle for a simple network consisting of only two routes are shown in Figure 4(a). Although the probability of traffic breakdown is an increasing flow rate function for each of the bottlenecks (Figure 3(c)), the probability of traffic breakdown in the network [math]\displaystyle{ P_\mathrm{net} }[/math] has a minimum as a function of the link inflow rates [math]\displaystyle{ q_1 }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ q_2 }[/math] (Figure 4(b, c)).

Alternative routes in a network

Before the BM principle is applied to a large traffic network, for each of the origin-destination (O–D) pairs of the network a set of alternative routes (paths) should be found. The alternative routes can be calculated based on the following assumptions: (i) there is free flow in the whole network and (ii) the maximum difference between travel times for alternative routes does not exceed a given value that can be chosen differently for different O–D pairs.

How to apply the BM principle if traffic breakdown has already occurred at a network bottleneck

Network optimization with measured features of traffic breakdown can consist of the stages: (i) A spatial limitation of congestion growth with the subsequent congestion dissolution at the bottleneck, if the dissolution of congestion due to traffic management in a neighborhood of the bottleneck is possible. (ii) The minimization of traffic breakdown probability with the BM principle in the remaining network, i.e., the network part that is not influenced by congestion.

The BM principle and classical Wardrop’s UE and SO principles

The BM principle is an alternative to well-known principles for vehicular network optimization and control based on the minimization of travel costs (travel time, fuel consumption, etc.) or the maximization of traffic throughput (like the maximization of band width of green wave in a city).[2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] In particular, the most prominent classical principles for the minimization of travel costs in a traffic network are Wardrop’s user equilibrium (UE) and system optimum (SO) principles[2] that are widely used in a theory of dynamic traffic assignment in the network.[4][6][13] Wardrop's SO and UE principles have been explained in Secs. 7.1 and 7.2 of Wikipedia article traffic flow.

However, when the flow rate on a link of a network is between the maximum and minimum capacities, there may be at least two different states of a bottleneck on the link denoted by circles F and S shown in Figure 3 (d). The state F is related to free flow and state S to synchronized flow. Therefore, hypothetically assuming that each of the link flow rates for each of the N network bottlenecks is between the associated minimum and maximum bottleneck capacities, we find that there may be [math]\displaystyle{ 2^N }[/math] different bottleneck states in the network at the same distribution of the flow rates in the network. If we apply an optimization algorithm associated with the minimization of travel cost in the network random transitions between these bottleneck states F and S may occur at different network bottlenecks during network optimization and/or control.

Rather than some travel costs, in the BM principle the objective function that should be minimized is the probability of traffic breakdown in the network [math]\displaystyle{ P_\mathrm{net} }[/math]. Thus the objective function in the BM principle that should be minimized depends neither on travel time nor other travel cost. The BM principle demands the minimization of the probability of traffic breakdown, i.e., the probability of the occurrence of congestion in the network. Under great traffic demand, the application of the BM principle should result in relatively small travel cost associated with free flow in a network.

See also

- Active traffic management

- Fundamental diagram

- Intelligent transportation system

- Microscopic traffic flow model

- Traffic wave

- Traffic bottleneck

- Traffic engineering (transportation)

- Traffic flow

- Three-phase traffic theory

- Traffic congestion

- Traffic congestion: Reconstruction with Kerner’s three-phase theory

- Transportation forecasting

Notes

- ↑ Kerner, Boris S (2011). "Optimum principle for a vehicular traffic network: Minimum probability of congestion". Journal of Physics A: Mathematical and Theoretical 44 (9): 092001. doi:10.1088/1751-8113/44/9/092001. Bibcode: 2011JPhA...44i2001K.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Wardrop J.G. (1952). Some theoretical aspects of road traffic research. In Proc. of Inst. of Civil Eng. II. Vol. 1, pp. 325–378.

- ↑ Daganzo C. F. and Sheffi Y. (1977). On Stochastic Models of Traffic Assignment. Transportation Science, 11, 253–274.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 M.G.H. Bell, Y. Iida (1997), Transportation network analysis, (John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, Hoboken, NJ 07030-6000 USA)

- ↑ C.F. Daganzo (1998), Transportation Science 32, 3–11

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 S. Peeta, A.K. Ziliaskopoulos (2001), Networks and Spatial Economics 1, 233–265

- ↑ H. Ceylan, M.G.H. Bell (2005), Transp. Res. B 39, 169–185

- ↑ Zhang, C., Chen, X., Sumalee, A. (2011). Robust Wardrop's user equilibrium assignment under stochastic demand and supply: Expected residual minimization approach. Transp. Res. B, Vol. 45, pp. 534–552.

- ↑ Hoogendoorn, S.P., Knoop, V.L., Van Zuylen, H.J. (2008). Robust control of traffic networks under uncertain conditions. J. Adv. Transp. Vol. 42, pp. 357–377.

- ↑ Wahle J., Bazzan A.L.C., Klugl F., Schreckenberg M. (2000), Decision dynamics in a traffic scenario. Physica A, Vol. 287, pp. 669–681.

- ↑ Davis L.C. (2009). Realizing Wardrop equilibria with real-time traffic information. Physica A, Vol. 388, pp. 4459–4474;

- ↑ Davis L.C. (2010). Predicting travel time to limit congestion at a highway bottleneck. Physica A, Vol. 389, pp. 3588–3599.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Rakha H., Tawfik A. (2009). Traffic Networks, Dynamic Traffic Routing, Assignment, and Assessment. In Encyclopedia of Complexity and System Science, ed. by R.A. Meyers. Springer, Berlin, pp. 9429–9470.

- ↑ Gartner N.H., Stamatiadis Ch. (2009). Traffic Networks, Optimization and Control of Urban. In Encyclopedia of Complexity and System Science, ed. by R.A. Meyers. Springer, Berlin, pp. 9470—9500.