Lindström–Gessel–Viennot lemma

In mathematics, the Lindström–Gessel–Viennot lemma provides a way to count the number of tuples of non-intersecting lattice paths, or, more generally, paths on a directed graph. It was proved by Gessel–Viennot in 1985, based on previous work of Lindström published in 1973.

Statement

Let G be a locally finite directed acyclic graph. This means that each vertex has finite degree, and that G contains no directed cycles. Consider base vertices [math]\displaystyle{ A = \{ a_1, \ldots, a_n \} }[/math] and destination vertices [math]\displaystyle{ B = \{ b_1, \ldots, b_n \} }[/math], and also assign a weight [math]\displaystyle{ \omega_{e} }[/math] to each directed edge e. These edge weights are assumed to belong to some commutative ring. For each directed path P between two vertices, let [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(P) }[/math] be the product of the weights of the edges of the path. For any two vertices a and b, write e(a,b) for the sum [math]\displaystyle{ e(a,b) = \sum_{P: a \to b} \omega(P) }[/math] over all paths from a to b. This is well-defined if between any two points there are only finitely many paths; but even in the general case, this can be well-defined under some circumstances (such as all edge weights being pairwise distinct formal indeterminates, and [math]\displaystyle{ e(a,b) }[/math] being regarded as a formal power series). If one assigns the weight 1 to each edge, then e(a,b) counts the number of paths from a to b.

With this setup, write

- [math]\displaystyle{ M = \begin{pmatrix} e(a_1,b_1) & e(a_1,b_2) & \cdots & e(a_1,b_n) \\ e(a_2,b_1) & e(a_2,b_2) & \cdots & e(a_2,b_n) \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ e(a_n,b_1) & e(a_n,b_2) & \cdots & e(a_n,b_n) \end{pmatrix} }[/math].

An n-tuple of non-intersecting paths from A to B means an n-tuple (P1, ..., Pn) of paths in G with the following properties:

- There exists a permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] of [math]\displaystyle{ \left\{ 1, 2, ..., n \right\} }[/math] such that, for every i, the path Pi is a path from [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ b_{\sigma(i)} }[/math].

- Whenever [math]\displaystyle{ i \neq j }[/math], the paths Pi and Pj have no two vertices in common (not even endpoints).

Given such an n-tuple (P1, ..., Pn), we denote by [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(P) }[/math] the permutation of [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] from the first condition.

The Lindström–Gessel–Viennot lemma then states that the determinant of M is the signed sum over all n-tuples P = (P1, ..., Pn) of non-intersecting paths from A to B:

- [math]\displaystyle{ \det(M) = \sum_{(P_1,\ldots,P_n) \colon A \to B} \mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P)) \prod_{i=1}^n \omega(P_i). }[/math]

That is, the determinant of M counts the weights of all n-tuples of non-intersecting paths starting at A and ending at B, each affected with the sign of the corresponding permutation of [math]\displaystyle{ (1,2,\ldots,n) }[/math], given by [math]\displaystyle{ P_i }[/math] taking [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ b_{\sigma(i)} }[/math].

In particular, if the only permutation possible is the identity (i.e., every n-tuple of non-intersecting paths from A to B takes ai to bi for each i) and we take the weights to be 1, then det(M) is exactly the number of non-intersecting n-tuples of paths starting at A and ending at B.

Proof

To prove the Lindström–Gessel–Viennot lemma, we first introduce some notation.

An n-path from an n-tuple [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n) }[/math] of vertices of G to an n-tuple [math]\displaystyle{ (b_1, b_2, \ldots, b_n) }[/math] of vertices of G will mean an n-tuple [math]\displaystyle{ (P_1, P_2, \ldots, P_n) }[/math] of paths in G, with each [math]\displaystyle{ P_i }[/math] leading from [math]\displaystyle{ a_i }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ b_i }[/math]. This n-path will be called non-intersecting just in case the paths Pi and Pj have no two vertices in common (including endpoints) whenever [math]\displaystyle{ i \neq j }[/math]. Otherwise, it will be called entangled.

Given an n-path [math]\displaystyle{ P = (P_1, P_2, \ldots, P_n) }[/math], the weight [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(P) }[/math] of this n-path is defined as the product [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(P_1) \omega(P_2) \cdots \omega(P_n) }[/math].

A twisted n-path from an n-tuple [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n) }[/math] of vertices of G to an n-tuple [math]\displaystyle{ (b_1, b_2, \ldots, b_n) }[/math] of vertices of G will mean an n-path from [math]\displaystyle{ (a_1, a_2, \ldots, a_n) }[/math] to [math]\displaystyle{ \left(b_{\sigma(1)}, b_{\sigma(2)}, \ldots, b_{\sigma(n)}\right) }[/math] for some permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] in the symmetric group [math]\displaystyle{ S_n }[/math]. This permutation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma }[/math] will be called the twist of this twisted n-path, and denoted by [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(P) }[/math] (where P is the n-path). This, of course, generalises the notation [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(P) }[/math] introduced before.

Recalling the definition of M, we can expand det M as a signed sum of permutations; thus we obtain

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{rcl} \det M &= &\sum_{\sigma\in S_{n}}\mathrm{sign}(\sigma)\prod_{i=1}^{n}e(a_{i},b_{\sigma(i)})\\ &= &\sum_{\sigma\in S_{n}}\mathrm{sign}(\sigma)\prod_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{P_{i}:a_{i}\to b_{\sigma(i)}}\omega(P_{i})\\ &= &\sum_{\sigma\in S_{n}}\mathrm{sign}(\sigma) \sum\{\omega(P):P~\text{an}~n\text{-path from}~\left(a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n\right)~\text{to}~\left(b_{\sigma(1)}, b_{\sigma(2)}, \ldots, b_{\sigma(n)}\right)\}\\ &= &\sum\{\mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P):P~\text{a twisted}~n\text{-path from}~\left(a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n\right)~\text{to}~\left(b_1, b_2, ..., b_n\right)\}\\ &= &\sum\{\mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P):P~\text{a non-intersecting twisted}~n\text{-path from}~\left(a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n\right)~\text{to}~\left(b_1, b_2, ..., b_n\right)\}\\ &&+\sum\{\mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P):P~\text{an entangled twisted}~n\text{-path from}~\left(a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n\right)~\text{to}~\left(b_1, b_2, ..., b_n\right)\}\\ &= &\sum_{(P_1,\ldots,P_n) \colon A \to B} \mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P)\\ &&+\underbrace{ \sum\{\mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P):P~\text{an entangled twisted}~n\text{-path from}~\left(a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n\right)~\text{to}~\left(b_1, b_2, ..., b_n\right)\}}_{=0?}\\ \end{array} }[/math]

It remains to show that the sum of [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P) }[/math] over all entangled twisted n-paths vanishes. Let [math]\displaystyle{ \mathcal{E} }[/math] denote the set of entangled twisted n-paths. To establish this, we shall construct an involution[math]\displaystyle{ f:\mathcal{E}\longrightarrow\mathcal{E} }[/math] with the properties [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(f(P))=\omega(P) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{sign}(\sigma(f(P)))=-\mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P)) }[/math] for all [math]\displaystyle{ P\in\mathcal{E} }[/math]. Given such an involution, the rest-term

- [math]\displaystyle{ \sum\{\mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P):P~\text{an entangled twisted}~n\text{-path from}~\left(a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_n\right)~\text{to}~\left(b_1, b_2, ..., b_n\right)\} = \sum_{P \in \mathcal{E}} \mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P))\omega(P) }[/math]

in the above sum reduces to 0, since its addends cancel each other out (namely, the addend corresponding to each [math]\displaystyle{ P \in \mathcal{E} }[/math] cancels the addend corresponding to [math]\displaystyle{ f(P) }[/math]).

Construction of the involution: The idea behind the definition of the involution [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is to take choose two intersecting paths within an entangled path, and switch their tails after their point of intersection. There are in general several pairs of intersecting paths, which can also intersect several times; hence, a careful choice needs to be made. Let [math]\displaystyle{ P = \left(P_1,P_2,...,P_n\right) }[/math] be any entangled twisted n-path. Then [math]\displaystyle{ f(P) }[/math] is defined as follows. We call a vertex crowded if it belongs to at least two of the paths [math]\displaystyle{ P_1,P_2,...,P_n }[/math]. The fact that the graph is acyclic implies that this is equivalent to "appearing at least twice in all the paths".[1] Since P is entangled, there is at least one crowded vertex. We pick the smallest [math]\displaystyle{ i \in \{1,2,\ldots,n\} }[/math] such that [math]\displaystyle{ P_i }[/math] contains a crowded vertex. Then, we pick the first crowded vertex v on [math]\displaystyle{ P_i }[/math] ("first" in sense of "encountered first when travelling along [math]\displaystyle{ P_i }[/math]"), and we pick the largest j such that v belongs to [math]\displaystyle{ P_j }[/math]. The crowdedness of v implies j > i. Write the two paths [math]\displaystyle{ P_i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ P_j }[/math] as

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{rcl} P_{i} &\equiv &a_{i}=u_{0}\to u_{1}\to u_{2}\ldots u_{\alpha-1}\to\overbrace{ \mathbf{u}_{\alpha}\to u_{\alpha+1} \ldots\to u_{r}=b_{\sigma(i)} }^{\mathrm{tail}~i}\\ P_{j} &\equiv &a_{j}=v_{0}\to v_{1}\to v_{2}\ldots v_{\beta-1}\to\underbrace{ \mathbf{v}_{\beta}\to v_{\beta+1} \ldots\to v_{s}=b_{\sigma(j)} }_{\mathrm{tail}~j}\\ \end{array} }[/math]

where [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma=\sigma(P) }[/math], and where [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math] are chosen such that v is the [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha }[/math]-th vertex along [math]\displaystyle{ P_i }[/math] and the [math]\displaystyle{ \beta }[/math]-th vertex along [math]\displaystyle{ P_j }[/math] (that is, [math]\displaystyle{ v = u_{\alpha} = v_{\beta} }[/math]). We set [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_P = \alpha }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta_P = \beta }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ i_{P} = i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j_{P} = j }[/math]. Now define the twisted n-path [math]\displaystyle{ f(P) }[/math] to coincide with [math]\displaystyle{ P }[/math] except for components [math]\displaystyle{ i }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ j }[/math], which are replaced by

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{rcl} P'_{i} &\equiv &a_{i}=u_{0}\to u_{1}\to u_{2}\ldots u_{\alpha-1}\to\overbrace{ v_{\beta_{P}}\to v_{\beta_{P}+1}\ldots\to v_{s}=b_{\sigma(j)} }^{\mathrm{tail}~j}\\ P'_{j} &\equiv &a_{j}=v_{0}\to v_{1}\to v_{2}\ldots v_{\beta-1}\to\underbrace{ u_{\alpha_{P}}\to u_{\alpha_{P}+1}\ldots\to u_{r}=b_{\sigma(i)} }_{\mathrm{tail}~i}\\ \end{array} }[/math]

It is immediately clear that [math]\displaystyle{ f(P) }[/math] is an entangled twisted n-path. Going through the steps of the construction, it is easy to see that [math]\displaystyle{ i_{f(P)}=i_{P} }[/math], [math]\displaystyle{ j_{f(P)}=j_{P} }[/math] and furthermore that [math]\displaystyle{ \alpha_{f(P)}=\alpha_{P} }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \beta_{f(P)}=\beta_{P} }[/math], so that applying [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] again to [math]\displaystyle{ f(P) }[/math] involves swapping back the tails of [math]\displaystyle{ f(P)_{i},f(P)_{j} }[/math] and leaving the other components intact. Hence [math]\displaystyle{ f(f(P))=P }[/math]. Thus [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] is an involution. It remains to demonstrate the desired antisymmetry properties:

From the construction one can see that [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(f(P)) }[/math] coincides with [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma=\sigma(P) }[/math] except that it swaps [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(i) }[/math] and [math]\displaystyle{ \sigma(j) }[/math], thus yielding [math]\displaystyle{ \mathrm{sign}(\sigma(f(P)))=-\mathrm{sign}(\sigma(P)) }[/math]. To show that [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(f(P))=\omega(P) }[/math] we first compute, appealing to the tail-swap

- [math]\displaystyle{ \begin{array}{rcl} \omega(P'_{i})\omega(P'_{j}) &= &\left(\prod_{t=0}^{\alpha-1}\omega(u_{t},u_{t+1})\cdot \prod_{t=\beta}^{s-1}\omega(v_{t},v_{t+1})\right) \cdot\left(\prod_{t=0}^{\beta-1}\omega(v_{t},v_{t+1})\cdot \prod_{t=\alpha}^{r-1}\omega(u_{t},u_{t+1})\right)\\ &= &\prod_{t=0}^{r-1}\omega(u_{t},u_{t+1})\cdot\prod_{t=0}^{s-1}\omega(v_{t},v_{t+1})\\ &= &\omega(P_{i})\omega(P_{j}).\\ \end{array} }[/math]

Hence [math]\displaystyle{ \omega(f(P))=\prod_{k=1}^{n}\omega(f(P)_{k})=\prod_{k=1,~k\neq i,j}^{n}\omega(P_{k})\cdot \omega(P'_{i})\omega(P'_{j})=\prod_{k=1,~k\neq i,j}^{n}\omega(P_{k})\cdot \omega(P_{i})\omega(P_{j})=\prod_{k=1}^{n}\omega(P_{k})=\omega(P) }[/math].

Thus we have found an involution with the desired properties and completed the proof of the Lindström-Gessel-Viennot lemma.

Remark. Arguments similar to the one above appear in several sources, with variations regarding the choice of which tails to switch. A version with j smallest (unequal to i) rather than largest appears in the Gessel-Viennot 1989 reference (proof of Theorem 1).

Applications

Schur polynomials

The Lindström–Gessel–Viennot lemma can be used to prove the equivalence of the following two different definitions of Schur polynomials. Given a partition [math]\displaystyle{ \lambda = \lambda_1 + \cdots + \lambda_r }[/math] of n, the Schur polynomial [math]\displaystyle{ s_\lambda(x_1,\ldots,x_n) }[/math] can be defined as:

- [math]\displaystyle{ s_\lambda(x_1,\ldots,x_n) = \sum_T w(T), }[/math]

where the sum is over all semistandard Young tableaux T of shape λ, and the weight of a tableau T is defined as the monomial obtained by taking the product of the xi indexed by the entries i of T. For instance, the weight of the tableau

is [math]\displaystyle{ x_1 x_3 x_4^3 x_5 x_6 x_7 }[/math].

is [math]\displaystyle{ x_1 x_3 x_4^3 x_5 x_6 x_7 }[/math].

- [math]\displaystyle{ s_\lambda(x_1, \ldots, x_n) = \det \left ( (h_{\lambda_i +j-i} )_{i,j}^{r \times r} \right ), }[/math]

where hi are the complete homogeneous symmetric polynomials (with hi understood to be 0 if i is negative). For instance, for the partition (3,2,2,1), the corresponding determinant is

- [math]\displaystyle{ s_{(3,2,2,1)} = \begin{vmatrix} h_3 & h_4 & h_5 & h_6 \\ h_1 & h_2 & h_3 & h_4 \\ 1 & h_1 & h_2 & h_3 \\ 0 & 0 & 1 & h_1 \end{vmatrix}. }[/math]

To prove the equivalence, given any partition λ as above, one considers the r starting points [math]\displaystyle{ a_i = (r+1-i,1) }[/math] and the r ending points [math]\displaystyle{ b_i = (\lambda_i + r+1-i, n) }[/math], as points in the lattice [math]\displaystyle{ \mathbb{Z}^2 }[/math], which acquires the structure of a directed graph by asserting that the only allowed directions are going one to the right or one up; the weight associated to any horizontal edge at height i is xi, and the weight associated to a vertical edge is 1. With this definition, r-tuples of paths from A to B are exactly semistandard Young tableaux of shape λ, and the weight of such an r-tuple is the corresponding summand in the first definition of the Schur polynomials. For instance, with the tableau

,

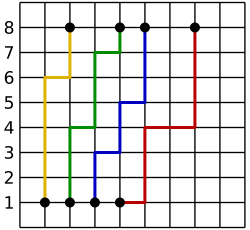

one gets the corresponding 4-tuple

,

one gets the corresponding 4-tuple

On the other hand, the matrix M is exactly the matrix written above for D. This shows the required equivalence. (See also §4.5 in Sagan's book, or the First Proof of Theorem 7.16.1 in Stanley's EC2, or §3.3 in Fulmek's arXiv preprint, or §9.13 in Martin's lecture notes, for slight variations on this argument.)

The Cauchy–Binet formula

One can also use the Lindström–Gessel–Viennot lemma to prove the Cauchy–Binet formula, and in particular the multiplicativity of the determinant.

Generalizations

Talaska's formula

The acyclicity of G is an essential assumption in the Lindström–Gessel–Viennot lemma; it guarantees (in reasonable situations) that the sums [math]\displaystyle{ e(a, b) }[/math] are well-defined, and it advects into the proof (if G is not acyclic, then f might transform a self-intersection of a path into an intersection of two distinct paths, which breaks the argument that f is an involution). Nevertheless, Kelli Talaska's 2012 paper establishes a formula generalizing the lemma to arbitrary digraphs. The sums [math]\displaystyle{ e(a, b) }[/math] are replaced by formal power series, and the sum over nonintersecting path tuples now becomes a sum over collections of nonintersecting and non-self-intersecting paths and cycles, divided by a sum over collections of nonintersecting cycles. The reader is referred to Talaska's paper for details.

See also

References

- ↑ If the graph was not acyclic, the "crowdedness" might change after applying [math]\displaystyle{ f }[/math] ; this proof would not work, and the lemma would actually become totally false.

- Gessel, Ira M.; Viennot, Xavier G. (1989), Determinants, Paths and Plane Partitions, http://contscience.xavierviennot.org/xavier/articles_files/determinant_89.pdf

- Lindström, Bernt (1973), On the vector representations of induced matroids, https://doi.org/10.1112/blms/5.1.8

- Sagan, Bruce E. (2001), The symmetric group, Springer

- Stanley, Richard P. (1999), Enumerative Combinatorics, volume 2, CUP

- Talaska, Kelli (2012), Determinants of weighted path matrices

- Martin, Jeremy (2012), Lecture Notes on Algebraic Combinatorics, http://jlmartin.faculty.ku.edu/CombinatoricsNotes.pdf

- Fulmek, Markus (2010), Viewing determinants as nonintersecting lattice paths yields classical determinantal identities bijectively

|