Mass matrix

In analytical mechanics, the mass matrix is a symmetric matrix M that expresses the connection between the time derivative of the generalized coordinate vector q of a system and the kinetic energy T of that system, by the equation

where denotes the transpose of the vector .[1] This equation is analogous to the formula for the kinetic energy of a particle with mass m and velocity v, namely

and can be derived from it, by expressing the position of each particle of the system in terms of q.

In general, the mass matrix M depends on the state q, and therefore varies with time.

Lagrangian mechanics yields an ordinary differential equation (actually, a system of coupled differential equations) that describes the evolution of a system in terms of an arbitrary vector of generalized coordinates that completely defines the position of every particle in the system. The kinetic energy formula above is one term of that equation, that represents the total kinetic energy of all the particles.

Examples

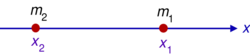

Two-body unidimensional system

For example, consider a system consisting of two point-like masses confined to a straight track. The state of that systems can be described by a vector q of two generalized coordinates, namely the positions of the two particles along the track.

Supposing the particles have masses m1, m2, the kinetic energy of the system is

This formula can also be written as

where

N-body system

More generally, consider a system of N particles labelled by an index i = 1, 2, …, N, where the position of particle number i is defined by ni free Cartesian coordinates (where ni = 1, 2, 3). Let q be the column vector comprising all those coordinates. The mass matrix M is the diagonal block matrix where in each block the diagonal elements are the mass of the corresponding particle:[2]

where Ini is the ni × ni identity matrix, or more fully:

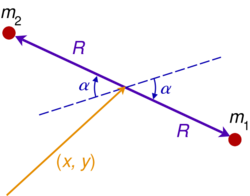

Rotating dumbbell

For a less trivial example, consider two point-like objects with masses m1, m2, attached to the ends of a rigid massless bar with length 2R, the assembly being free to rotate and slide over a fixed plane. The state of the system can be described by the generalized coordinate vector

where x, y are the Cartesian coordinates of the bar's midpoint and α is the angle of the bar from some arbitrary reference direction. The positions and velocities of the two particles are

and their total kinetic energy is

where and . This formula can be written in matrix form as

where

Note that the matrix depends on the current angle α of the bar.

Continuum mechanics

For discrete approximations of continuum mechanics as in the finite element method, there may be more than one way to construct the mass matrix, depending on desired computational accuracy and performance. For example, a lumped-mass method, in which the deformation of each element is ignored, creates a diagonal mass matrix and negates the need to integrate mass across the deformed element.

See also

References

- ↑ Mathematical methods for physics and engineering, K.F. Riley, M.P. Hobson, S.J. Bence, Cambridge University Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-521-86153-3

- ↑ Analytical Mechanics, L.N. Hand, J.D. Finch, Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978 0 521 57572 0

|