Medicine:Epidemiology of typhoid fever

In 2000, typhoid fever caused an estimated 21.7 million illnesses and 217,000 deaths.[1] It occurs most often in children and young adults between 5 and 19 years old.[2] In 2013, it resulted in about 161,000 deaths – down from 181,000 in 1990.[3] Infants, children, and adolescents in south-central and Southeast Asia experience the greatest burden of illness.[4] Outbreaks of typhoid fever are also frequently reported from sub-Saharan Africa and countries in Southeast Asia.[5][6][7] In the United States, about 400 cases occur each year, and 75% of these are acquired while traveling internationally.[8][9]

Historically, before the antibiotic era, the case fatality rate of typhoid fever was 10–20%. Today, with prompt treatment, it is less than 1%.[10] However, about 3–5% of individuals who are infected develop a chronic infection in the gall bladder.[11] Since S. e. subsp. enterica is human-restricted, these chronic carriers become the crucial reservoir, which can persist for decades for further spread of the disease, further complicating the identification and treatment of the disease.[12] Lately, the study of S. e. subsp. enterica associated with a large outbreak and a carrier at the genome level provides new insights into the pathogenesis of the pathogen.[13][14]

In industrialized nations, water sanitation and food handling improvements have reduced the number of cases.[15] Developing nations, such as those found in parts of Asia and Africa, have the highest rates of typhoid fever. These areas have a lack of access to clean water, proper sanitation systems, and proper health-care facilities. For these areas, such access to basic public-health needs is not in the near future.[16]

Ancient Greece

In 430 BCE, a plague, which some believe to have been typhoid fever, killed one-third of the population of Athens, including their leader Pericles. Following this disaster, the balance of power shifted from Athens to Sparta, ending the Golden Age of Pericles that had marked Athenian dominance in the Greek ancient world. The ancient historian Thucydides also contracted the disease, but he survived to write about the plague. His writings are the primary source of information on this outbreak, and modern academics and medical scientists consider typhoid fever the most likely cause. In 2006, a study detected DNA sequences similar to those of the bacterium responsible for typhoid fever in dental pulp extracted from a burial pit dated to the time of the outbreak.[17]

The cause of the plague has long been disputed and other scientists have disputed the findings, citing serious methodologic flaws in the dental pulp-derived DNA study.[18] The disease is most commonly transmitted through poor hygiene habits and public sanitation conditions; during the period in question related to Athens above, the whole population of Attica was besieged within the Long Walls and lived in tents.[citation needed]

16th and 17th centuries

A pair of epidemics struck the Mexican highlands in 1545 and 1576, causing an estimated 7 to 17 million deaths.[19] A study published in 2018 suggests that the cause was typhoid fever.[20][21]

Some historians believe that the English colony of Jamestown, Virginia, died out from typhoid. Typhoid fever killed more than 6,000 settlers in the New World between 1607 and 1624.[22]

Nineteenth century

A long-held belief is that 9th US President William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia, but recent studies suggest he likely died from typhoid.

This disease may also have been a contributing factor in the death of 12th US President Zachary Taylor due to the unsanitary conditions in Washington, DC, in the mid-19th century.[23][24]

During the American Civil War, 81,360 Union soldiers died of typhoid or dysentery, far more than died of battle wounds.[25] In the late 19th century, the typhoid fever mortality rate in Chicago averaged 65 per 100,000 people a year. The worst year was 1891, when the typhoid death rate was 174 per 100,000 people.[26]

During the Spanish–American War, American troops were exposed to typhoid fever in stateside training camps and overseas, largely due to inadequate sanitation systems. The Surgeon General of the Army, George Miller Sternberg, suggested that the War Department create a Typhoid Fever Board. Major Walter Reed, Edward O. Shakespeare, and Victor C. Vaughan were appointed August 18, 1898, with Reed being designated the president of the board. The Typhoid Board determined that during the war, more soldiers died from this disease than from yellow fever or from battle wounds. The board promoted sanitary measures including latrine policy, disinfection, camp relocation, and water sterilization, but by far the most successful antityphoid method was vaccination, which became compulsory in June 1911 for all federal troops.[27]

Twentieth century

In 1902, guests at mayoral banquets in Southampton and Winchester, England, became ill and four died, including the Dean of Winchester, after consuming oysters. The infection was due to oysters sourced from Emsworth, where the oyster beds had been contaminated with raw sewage.[28][29]

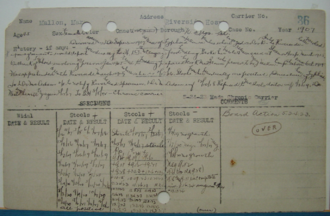

The most notorious carrier of typhoid fever, but by no means the most destructive, was Mary Mallon, also known as Typhoid Mary. In 1907, she became the first carrier in the United States to be identified and traced. She was a cook in New York, who was closely associated with 53 cases and three deaths.[30] Public-health authorities told Mary to give up working as a cook or have her gall bladder removed, as she had a chronic infection that kept her active as a carrier of the disease. Mary quit her job, but returned later under a false name. She was detained and quarantined after another typhoid outbreak. She died of pneumonia in 1938, after 26 years in quarantine.[31][32]

A well-publicised outbreak occurred in Croydon, Surrey, now part of London, in 1937. [33]It resulted in 341 cases of typhoid (43 fatal),[34][35]and it caused considerable local discontent.[36][37][38] While repair work was being performed on the primary well, the water supply was no longer being filtered and chlorinated. The infection was traced to one repair workman, who was (unwittingly) an active carrier of typhoid. [39]

A notable outbreak occurred in Aberdeen, Scotland, in 1964, due to contaminated tinned meat sold at the city's branch of the William Low chain of stores. There were three deaths connected with the outbreak,[40] and over 400 cases were diagnosed. [41]

Twenty-first century

In 2004–05 an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo resulted in more than 42,000 cases and 214 deaths.[2] Since November 2016, Pakistan has had an outbreak of extensively drug-resistant (XDR) typhoid fever.[42]

References

- ↑ "Global trends in typhoid and paratyphoid Fever". Clinical Infectious Diseases 50 (2): 241–6. January 2010. doi:10.1086/649541. PMID 20014951.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Typhoid Fever". World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/vaccine_research/diseases/diarrhoeal/en/index7.html.

- ↑ GBD 2013 Mortality Causes of Death Collaborators (January 2015). "Global, regional, and national age-sex specific all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 240 causes of death, 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013". Lancet 385 (9963): 117–71. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61682-2. PMID 25530442.

- ↑ "The global burden of typhoid fever". Bull World Health Organ 82 (5): 346–353. 2004. PMID 15298225.

- ↑ "An outbreak of peritonitis caused by multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhi in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo". Travel Medicine and Infectious Disease 7 (1): 40–3. January 2009. doi:10.1016/j.tmaid.2008.12.006. PMID 19174300.

- ↑ "Genetic fine structure of a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strain associated with the 2005 outbreak of typhoid fever in Kelantan, Malaysia". Journal of Bacteriology 194 (13): 3565–6. July 2012. doi:10.1128/jb.00581-12. PMID 22689247.

- ↑ "Insights from the genome sequence of a Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strain associated with a sporadic case of typhoid fever in Malaysia". Journal of Bacteriology 194 (18): 5124–5. September 2012. doi:10.1128/jb.01062-12. PMID 22933756.

- ↑ Matano, Leigh M.; Morris, Heidi G.; Wood, B. McKay; Meredith, Timothy C.; Walker, Suzanne (December 15, 2016). "Accelerating the discovery of antibacterial compounds using pathway-directed whole cell screening". Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 24 (24): 6307–6314. doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2016.08.003. ISSN 1464-3391. PMID 27594549.

- ↑ http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/disease-reporting-and-management/disease-reporting-and-surveillance/_documents/gsi-typhoid-fever.pdf

- ↑ Heymann, David L., ed. (2008), Control of Communicable Diseases Manual, Washington, D.C.: American Public Health Association, pg 665. ISBN 978-0-87553-189-2.

- ↑ "Precise estimation of the numbers of chronic carriers of Salmonella typhi in Santiago, Chile, an endemic area". The Journal of Infectious Diseases 146 (6): 724–6. December 1982. doi:10.1093/infdis/146.6.724. PMID 7142746.

- ↑ "Chronic and acute infection of the gall bladder by Salmonella Typhi: understanding the carrier state". Nature Reviews. Microbiology 9 (1): 9–14. January 2011. doi:10.1038/nrmicro2490. PMID 21113180.

- ↑ "Genome sequence and comparative pathogenomics analysis of a Salmonella enterica Serovar Typhi strain associated with a typhoid carrier in Malaysia". Journal of Bacteriology 194 (21): 5970–1. November 2012. doi:10.1128/jb.01416-12. PMID 23045488.

- ↑ "Comparative genomics of closely related Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi strains reveals genome dynamics and the acquisition of novel pathogenic elements". BMC Genomics 15 (1): 1007. November 2014. doi:10.1186/1471-2164-15-1007. PMID 25412680.

- ↑ "Epidemiology, Clinical Presentation, Laboratory Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Resistance, and Antimicrobial Management of Invasive Salmonella Infections". Clinical Microbiology Reviews 28 (4): 901–37. October 2015. doi:10.1128/CMR.00002-15. PMID 26180063.

- ↑ "Typhoid vaccine introduction: An evidence-based pilot implementation project in Nepal and Pakistan". Vaccine 33 Suppl 3: C62-7. June 2015. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.03.087. PMID 25937612.

- ↑ "DNA examination of ancient dental pulp incriminates typhoid fever as a probable cause of the Plague of Athens". International Journal of Infectious Diseases 10 (3): 206–14. May 2006. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2005.09.001. PMID 16412683.

- ↑ "No proof that typhoid caused the Plague of Athens (a reply to Papagrigorakis et al.)". International Journal of Infectious Diseases 10 (4): 334–5; author reply 335–6. July 2006. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2006.02.006. PMID 16730469.

- ↑ "Megadrought and megadeath in 16th century Mexico". Emerging Infectious Diseases 8 (4): 360–2. April 2002. doi:10.3201/eid0804.010175. PMID 11971767.

- ↑ Hersher, Rebecca (January 15, 2018). "Salmonella May Have Caused Massive Aztec Epidemic, Study Finds". NRP. https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2018/01/15/577681552/salmonella-may-have-caused-massive-aztec-epidemic-study-finds.

- ↑ "Salmonella enterica genomes from victims of a major sixteenth-century epidemic in Mexico". Nature Ecology & Evolution 2 (3): 520–528. March 2018. doi:10.1038/s41559-017-0446-6. PMID 29335577.

- ↑ Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=5Pvi-ksuKFIC&pg=PA190&dq#v=onepage&q=&f=false.

- ↑ "Death in the White House: President William Henry Harrison's Atypical Pneumonia". Clinical Infectious Diseases 59 (7): 990–5. October 2014. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu470. PMID 24962997.

- ↑ Mchugh, Jane; Mackowiak, Philip A. (March 31, 2014). "What Really Killed William Henry Harrison?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/04/01/science/what-really-killed-william-henry-harrison.html.

- ↑ Armies of Pestilence: The Effects of Pandemics on History . James Clarke & Co. (2004). p.191. ISBN 0-227-17240-X

- ↑ "1900 Flow of Chicago River Reversed". Chicago Public Library. http://www.chipublib.org/004chicago/timeline/riverflow.html.

- ↑ "Walter Reed Typhoid Fever, 1897–1911". http://exhibits.hsl.virginia.edu/typhoid/., Claude Moore Health Sciences Library. University of Virginia.

- ↑ "Emsworth Oysters". Emsworth Business Association. February 10, 2019. http://www.emsworth.org.uk/news/emsworths-oysters-video-now-online.

- ↑ Bulstrode, H. Timbrell (1903). Dr. H. Timbrell Bulstrode's report to the Local Government Board upon alleged oyster-borne enteric fever and other illness following the mayoral banquets at Winchester and Southampton, and upon enteric fever occurring simultaneously elsewhere and also ascribed to oysters. London: HMSO. p. 1. https://archive.org/stream/b24914812#page/n0/mode/2up.

- ↑ "Nova: The Most Dangerous Woman in America". https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/typhoid/letter.html.

- ↑ "'TYPHOID MARY' DIES OF A STROKE AT 68; Carrier of Disease, Blamed for 51 Cases and 3 Deaths, but She Was Held Immune Services This Morning Epidemic Is Traced" (in en). The New York Times. November 12, 1938. https://www.nytimes.com/1938/11/12/archives/typhoid-mary-dies-of-a-stroke-at-68-carrier-of-disease-blamed-for.html?searchResultPosition=12.

- ↑ "Typhoid Mary's tragic tale exposed the health impacts of 'super-spreaders'" (in en). National Geographic. March 18, 2020. https://www.nationalgeographic.co.uk/history-and-civilisation/2020/03/typhoid-marys-tragic-tale-exposed-health-impacts-of-super.

- ↑ info copied from Croydon typhoid outbreak of 1937; see that article for attribution and history

- ↑ Pennington, T. Hugh (2003). When Food Kills : BSE, E.coli and disaster science: BSE, E.coli and disaster science. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 29–31. ISBN 0-19-8525176. https://books.google.com/books?id=vw7DVnS4RWYC&pg=PA29.

- ↑ Holden, O. M. (October 1938). "The croydon typhoid outbreak (A Summary of the Chief Clinical Features)". Public Health 52: 135–146. doi:10.1016/S0033-3506(38)80123-2. ISSN 0033-3506.

- ↑ David F. Smith, H. Lesley Diack, T. Hugh Pennington, Thomas Hugh Pennington, Elizabeth M. Russell (2005). Food Poisoning, Policy, and Politics: Corned Beef and Typhoid in Britain in the 1960s. The Boydell Press. p. 13. ISBN 1-84383-138-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=gL72g21APeEC&pg=PA13.

- ↑ "Croydon Typhoid Inquiry: Closing Proceedings". The British Medical Journal 1 (4019): 135–137. 1938. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.4019.135. ISSN 0007-1447. PMID 20781171.

- ↑ Goddard, Nick (29 November 2005). "Croydon Typhoid Outbreak of 1937". https://www.bbc.co.uk/radio4/history/making_history/making_history_20051129.shtml.

- ↑ Murphy, H. L. (19 February 1938). "Croydon Typhoid Inquiry: Mr. Murphy's Report". British Medical Journal 1 (4024): 404–407. ISSN 0007-1447. PMID 20781269.

- ↑ "Aberdeen Typhoid Outbreak of 1964". British Medical Journal: 601. 10 September 1966. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5514.601. https://www.bmj.com/content/2/5514/601.full.pdf. Retrieved 12 March 2020.

- ↑ "Records of Tor-na-Dee Hospital, Milltimber". http://calms.abdn.ac.uk/DServe/dserve.exe?dsqServer=Calms&dsqIni=Dserve.ini&dsqApp=Archive&dsqCmd=Show.tcl&dsqDb=Catalog&dsqPos=0&dsqSearch=%28RefNo%3D%27grhb%2025%27%29. Retrieved 13 March 2020.

- ↑ "Extensively Drug-Resistant Typhoid Fever in Pakistan". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 30, 2019. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/notices/watch/xdr-typhoid-fever-pakistan.