Medicine:Gourmand syndrome

| Gourmand syndrome | |

|---|---|

| |

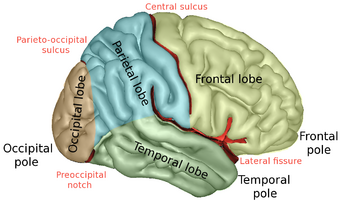

| Frontal lobe (at right) | |

| Specialty | Neurology |

Gourmand syndrome is a very rare and benign eating disorder that usually occurs six to twelve months after an injury to the frontal lobe.[1][2][3][4] Those with the disorder usually have a right hemisphere frontal or temporal brain lesion typically affecting the cortical areas, basal ganglia or limbic structures.[3][2][5][6] These people develop a new, post-injury passion for gourmet food.[3][2][5][4]

There are two main aspects of gourmand syndrome: first, the fine dining habits and changes to taste, and second, the obsessive component, which may result in craving and preservation.[2] Gourmand syndrome can be related to, and shares biological features with, addictive and obsessive disorders.[2][3] The syndrome was first characterised in 1997.[3]

Signs and symptoms

A new-found obsession for refined foods after frontal lobe injury is the primary characterization of Gourmand syndrome.[2][1][3][4][5][6][excessive citations]

Causes

It is believed that the frontotemporal circuits, normally involved in healthy eating, can, when injured, cause gourmand syndrome in patients.[4]

History

Only 36 people had been diagnosed with gourmand syndrome as of 2001.[6] In many of these cases, the patient did not have any interest in food beforehand nor had any family history with eating disorders.[5][2][3]

The first, most famous case was seen in 1997 by Regard and Landis in the journal Neurology:[2][3] after a Swiss stroke patient was released from the hospital, he immediately quit his job as a political journalist and took up the profession of food critic.[3] Regard and Landis also observed an athletic businessman with this condition whose family was shocked to see such a sudden, drastic change in his diet.[3]

Only one case of gourmand syndrome has been reported in a child. He was born with issues with his right temporal lobe; at eight years old he began to experience seizures, within the year of the seizures beginning, his behavior began to change to the symptoms of gourmand syndrome.[2]

In 2014, a man that was once interested in marathon running now was only interested in gastronomy, traveling hundreds or thousands of miles to eat gourmet food. He became a famous gastronomic critic and gained 50 kg (110 pounds).[5]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pascual-Leone, Alvaro; Alonso-Alonso, Miguel (2007-04-25). "The Right Brain Hypothesis for Obesity" (in en). JAMA 297 (16): 1819–1822. doi:10.1001/jama.297.16.1819. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 17456824.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 Kurian, M.; Schmitt-Mechelke, T.; Korff, C.; Delavelle, J.; Landis, T.; Seeck, M. (2008). ""Gourmand syndrome" in a child with pharmacoresistant epilepsy". Epilepsy & Behavior 13 (2): 413–415. doi:10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.04.004. PMID 18502182.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 Regard, Marianne; Landis, Theodor (1997). ""Gourmand syndrome": Eating passion associated with right anterior lesions". Neurology 48 (5): 1185–1190. doi:10.1212/WNL.48.5.1185. PMID 9153440.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Uher, R.; Treasure, J. (2004). "Brain lesions and eating disorders". J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 76 (6): 852–857. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.048819. PMID 15897510.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Gallo, M.; Gámiz, F.; Perez-Garíca, M.; Morals, R.; Rolls, T. (2014). "Taste and olfactory status in a gourmand with a right amygdala lesion". Neurocase 20 (4): 421–433. doi:10.1080/13554794.2013.791862. PMID 23668221.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Cummings, Jeffery L.; Lichter, David G. (2001). Frontal-Subcortical Circuits in Psychiatric and Neurological Disorders. New York, London: Guliford Press. pp. 167–169. ISBN 1-57230-623-8.

Further reading

- Uher, R (2005). "Brain lesions and eating disorders". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 76 (6): 852–7. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.048819. PMID 15897510.

- Bramen, Lisa (2011-07-06). "Gourmand Syndrome – First identified by neuroscientists in the 1990s, the disorder is marked by "a preoccupation with food and a preference for fine eating". Smithsonian.com. http://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/gourmand-syndrome-26067295/.

|