Medicine:Post-traumatic stress disorder after World War II

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) results after experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event which later leads to mental health problems.[1] This disorder has always existed but has only been recognized as a psychological disorder within the past forty years.[2][3][4] Before receiving its official diagnosis in 1980, when it was published in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-lll),[2] Post-traumatic stress disorder was more commonly known as soldier's heart, irritable heart, or shell shock.[2][3][4][5][6] Shell shock and war neuroses were coined during World War I when symptoms began to be more commonly recognized among many of the soldiers that had experienced similar traumas.[2][3][5][6] By World War II, these symptoms were identified as combat stress reaction or battle fatigue.[2][3][6] In the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I), post-traumatic stress disorder was called gross stress reaction which was explained as prolonged stress due to a traumatic event.[2] Upon further study of this disorder in World War II veterans, psychologists realized that their symptoms were long-lasting and went beyond an anxiety disorder.[2][7] Thus, through the effects of World War II, post-traumatic stress disorder was eventually recognized as an official disorder in 1980.[2][3][4]

General overview

Changing terminology

Nostalgia, soldier's heart, and railway spine

The term nostalgia was first coined in 1761 when soldiers reported feeling homesick, sleep disturbances, and anxiety after being in combat.[2] Later, soldier's heart was used to describe these symptoms but instead blamed cardiac problems as the source of anxiety and overstimulation.[2][5] Railway spine also explained physical causes for PTSD symptoms. After railroad accidents became more common, the victims of these accidents exhibited emotional distress.[2]

Shell shock and war neuroses

Before the term post-traumatic stress disorder was established, people that exhibited symptoms were said to have shell shock[6][5][2][3] or war neuroses.[8][3][9] This terminology came about in WWI when a commonality among combat soldiers was identified during psychiatric evaluations.[3] These soldiers all appeared to be in a catatonic state following battle, or "shocked by shells",[3] hence the term shell shocked.

Battle fatigue and combat stress reaction

During World War II, the diagnosis for shell shock was replaced with combat stress reaction.[6][2][3] These diagnoses resulted from soldiers being in combat for long periods of time.[2] There was some skepticism surrounding this diagnosis as some military leadership, including George S. Patton did not believe "battle fatigue" to be real.[2] Yet, due to evolving practices, such as proximity, immediacy, and expectancy (PIE), this new diagnosis was taken seriously and recovery was made the first priority.[2]

Prevalence

Post-traumatic stress disorder has always been prevalent whether it was recognized as a psychological disorder or not.[2][3][4] Yet, because PTSD was not recognized as an official disorder, it is difficult to estimate what the prevalence rate during WWII was.[5] A rough estimate, found through hospitalization records, suggests that approximately 43 per 1000 soldiers were hospitalized due to war traumas.[3] Again, however, this estimate is only based upon those who actually sought help, with many at this time not seeking help. Another prevalence rate, found in the 1950s, suggests that about 10% of WWII soldiers had PTSD at some point.[9] While it is difficult to retroactively discern prevalence for PTSD in WWII soldiers, what is clear is that it is prevalent now more than ever due to the long-lasting effects of combat in World War II. For example, half of all male veterans 65 and older have had military experience, which predisposes them to the acquisition of PTSD.[1] Thus, PTSD continues to affect World War II veterans and their families.

Symptoms

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder differ from person to person in that they can begin shortly after a traumatic event or even years after the event.[2][10] Moreover, symptoms can continue to present long after the traumatic event's occurrence, with some people experiencing symptoms for the rest of their lives.[10] Symptoms of PTSD can be grouped into four main categories: "Intrusive memories, avoidance, negative changes in thinking and mood, and changes in physical and emotional reactions".[10]

- Intrusive memories can include symptoms such as nightmares, flashbacks, recurring memories of the event, and emotional and physical stress upon encountering things that remind them of their trauma.[4][10]

- Symptoms for avoidance behavior include avoiding thoughts and conversations surrounding the event, as well as people, places, or other things that remind them of what happened.[10] This, understandably, occurs due to intrusive memories that persistently take place, which makes PTSD patients want to avoid these feelings.

- Negative changes in thinking and mood can force patients into experiencing memory loss (especially in regard to the traumatic event), hopelessness about themselves and their future, difficulty maintaining relationships,[11][12][13] and a struggle in experiencing positive emotions.[10]

- Changes in physical and emotional reactions are seen through behaviors such as trouble sleeping, difficulty concentrating, always being on guard, and becoming startled easily.[10][14] Some people experience these symptoms when they hear unexpected loud noises,[1][10] which causes them to "[lose] their cool over minor everyday things".[1] Other symptoms can include self-destructive actions such as excessive drinking or driving too fast and outbursts of anger or overwhelming guilt.[14][10]

Treatment

Treatments used during WWII

New treatment methods for PTSD emerged during WWII, likely due to the high demand for care, and the subsequent increase in investigation.[8][7] Interestingly, despite little understanding of the mechanisms whereby PTSD happened, much of the early interventions by psychiatrists in the 1940s remain similar to the methods still used today, such as medications and group therapy.[7][2]

One early treatment plan, from 1944, suggests a three part treatment to PTSD through use of sedatives to secure rest; use of intravenous barbiturates to promote mental catharsis, thereby assisting in the recall of a suppressed episode and use of drugs acting directly on the autonomic nervous system.[7] In addition to medication plans, another method that was utilized for PTSD during WWII was the principle of proximity, immediacy, and expectancy, or "PIE".[2] In essence, the PIE method emphasized immediate action in the treatment of PTSD. While first treatment plans for PTSD were crude and simplistic, they represent the rapidly changing field of psychiatry that WWII initiated, as will be further discussed below.

Broader impacts

Divorce rates following WWII

Following WWII, the high rates of shell-shocked veterans and prisoners of war (POWs) returning home largely impacted marital relationships. A correlation between war and higher divorce rates is typical,[11] and extends to WWII vets, specifically ex-POWs since the rates of PTSD are much higher for this group.[12] For example, it was found that 30% of POWs with PTSD experienced relationship problems, with only 11% of veterans without PTSD experiencing marital problems.[12] Moreover, a different study found that being in active combat or on the front lines also increased likelihood of marital discord.[11][13] From this, it can be suggested that those who have been in high stress situations, and have subsequently developed PTSD, have a higher prevalence of marital problems than those without PTSD. Those with PTSD likely have more marital problems due to slow adjustment back home, a lack of valuable communication/expression, intimacy problems, life disruption, economic problems, aggression, and lingering mental health impacts.[15][12][11] Thus, the effects of PTSD on WWII vets were not isolated to the vets themselves, as evidenced through high rates of marital discord following the war.

Development of psychiatry

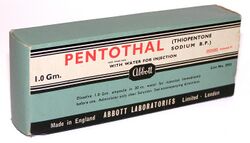

During WWII the field of psychiatry was beginning to evolve, with a specific emphasis on military psychiatry due to the high rates of PTSD in soldiers.[8][7] This can be seen in the changing technologies and aims of the American Psychological Association (APA) during the years that the United States was fighting in WWII. For example, between the years of 1943 and 1944, APA went from claiming that fear was the mechanism behind PTSD to attempting to understand the real underlying processes of PTSD,[7] which represents a change in understanding of mental illnesses. Additionally, these years in APA history represent a switch from suggesting rest to soldiers to prescribing medications and having specified treatment plans.[7] These changes in understanding were important to evolving psychiatry into what it is today; yet, the ideas about PTSD during WWII were still in their infancy, meaning that psychiatrists during WWII made some unethical choices.[8] For example, two famous military psychiatrists by the names of Roy Grinker and Frederick Hanson implemented mandatory sodium pentothal treatments, which were intended to induce the truth during psychoanalysis for soldiers claiming "exhaustion".[8] These treatments have since been proven harmful rather than helpful.[8][7] Yet, it was through these initial contributions that the DSM-I was published in 1952,[2] thus proving WWII as a pivotal time for the advancement of psychiatry.[2][3][4]

Personal accounts

The impacts of PTSD from wartime trauma varies from person to person, yet the degree of trauma often indicates the severity of the PTSD.[16][1] Additionally, other pre-existing factors, such as personality or preparedness,[3][1][14] also play into the development of PTSD in a veteran. Much like how no two people are alike, no two veterans will have the exact same experiences with PTSD, yet, there can still be commonalities such as negative homecoming experiences or lack of social support.[1] With this being said, one way to gain a better understanding of both the similarities and differences of PTSD among WWII veterans is through reading first-hand accounts which emphasize both the chronicity and longevity of war-time PTSD.

Earl Crumby

71 years after the Battle of the Bulge, Earl Crumby sat down with Tim Madigan in 2015 to be interviewed about his part in it. At the time of the interview, his wife had just recently died and yet, he is quoted as saying, "as dearly as I loved that woman, her death didn’t affect me near as much as it does to sit down here and talk to you about seeing those young boys butchered during the war. It was nothing but arms and legs, heads and guts".[17] This personal account of Crumby's emphasizes just how intense these experiences were/are as well as underscores the chronicity of PTSD in WWII veterans.

Otis Mackey

When Otis Mackey was interviewed by Tim Madigan in 2015, his traumatic war experiences had not diminished over the years, but rather had increased in severity. Mackey is quoted saying, "I get that empty feeling, just deep down, and I don’t care whether I live or die".[17] In addition to emptiness, Mackey also has strong flashbacks of comrades being blown up and intense nightmares of bombs going off. "I seen it coming at me. I just ducked, and McGhee’s leg went flying right by my head...I never could figure out why it was him and not me".[17] This personal account of Mackey's emphasizes the severity of PTSD, even decades after his WWII service.

Dutch Shultz

Portrayed in the 1962 movie, The Longest Day, Dutch Shultz is remembered as an innocent and happy paratrooper. Yet, this idealized version bears little resemblance to the real Shultz, who is quoted as saying, "people did not want to know what it was like".[18] Based on accounts from Shultz's daughter, Carol, her father was always drinking in order to take the pain of war away. Additionally, according to Carol, her father "would wake up with nightmares every single day",[18] and even tried to take his own life. This account from both Shultz and his daughter emphasize both the chronicity and longevity of the traumas of war as well as shows that PTSD did not just impact those with the disorder. Dutch Shultz never got help for his PTSD, and Carol went her entire life having a half-present, drunk father.

Roy "Eric" Cooper

Roy "Eric" Cooper fought at Burma, and according to his daughter Ceri-Ann, "every second of every day, Burma was with him, even to his last breath".[18] While he was alive, Cooper is quoted as saying troubling things such as, "I don’t feel very well in my mind and I am a bad man".[18] Much like the other accounts, this account emphasizes the longevity of his war traumas as well as the hopelessness in Cooper's life.

Anonymous Accounts

In 2011, researchers [19] collected quotes from survivors of WWII atomic bombs in order to determine the level of health among survivors. The survivors of these bombings range in age from 75 to 92, with both veterans and non-veterans included. Non-veteran's experiences are often overlooked, however their levels of health were similar to those who had seen combat.[19] This suggests that non-veteran's experiences with PTSD can be just as severe, and therefore important, as that of veteran's experiences. The following anonymous quote is one of many from the 2011 research [19] that suggests that the trauma seen within WWII has a strong relationship to a lifetime of PTSD.

There were too many kids in the water. And it's hard to pass up someone in the water. We saw real early on that . . . the ones that were squished bad . . . you couldn't get em' in the launch. You couldn't do nothing for em' . . . We took loads of em' and we could hold about 60 . . . In the meantime, we went back out and it just kept repeatin' itself.[19]

The above quote is from a veteran who experienced the bombing at Pearl Harbor, which was a traumatic event that influenced both veteran and non-veteran [19] development of PTSD.

See also

- Post-traumatic stress disorder

- Combat stress reaction

- Psychological trauma

- National trauma

- Complex post-traumatic stress disorder

- Old sergeant's syndrome

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Kang, Sungrok; Aldwin, Carolyn M.; Choun, Soyoung; Spiro, Avron (2016-02-01). "A Life-span Perspective on Combat Exposure and PTSD Symptoms in Later Life: Findings From the VA Normative Aging Study" (in en). The Gerontologist 56 (1): 22–32. doi:10.1093/geront/gnv120. ISSN 0016-9013. PMID 26324040.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 Friedman, Matthew. "History of PTSD in Veterans: Civil War to DSM-5 – PTSD: National Center for PTSD" (in en). https://www.ptsd.va.gov/understand/what/history_ptsd.asp.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 Crocq, M. A.; Crocq, L. (2000). "From shell shock and war neurosis to posttraumatic stress disorder: a history of psychotraumatology". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience 2 (1): 47–55. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2000.2.1/macrocq. ISSN 1294-8322. PMID 22033462.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Kolk, Bessel van der; Najavits, Lisa M. (2013). "Interview: What is PTSD Really? Surprises, Twists of History, and the Politics of Diagnosis and Treatment" (in en). Journal of Clinical Psychology 69 (5): 516–522. doi:10.1002/jclp.21992. ISSN 1097-4679. PMID 23592047. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/jclp.21992.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Langer, Ron. "Combat trauma, memory, and the World War II veteran." War, Literature, and the Arts: An International Journal of the Humanities 23, no. 1 (2011): 50–58. http://www.pitt.edu/~nancyp/uhc-1510/CombatTraumaMemoryWWIIVet.pdf

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Spiller, Roger (1990). "Shellshock". https://www.americanheritage.com/shellshock.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 Stein, Murray B.; Rothbaum, Barbara O. (2018-06-01). "175 Years of Progress in PTSD Therapeutics: Learning From the Past". American Journal of Psychiatry 175 (6): 508–516. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17080955. ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 29869547.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Boone, Katherine; Richardson, Frank (2010). "APA PsycNet". Journal of Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology 30 (2): 109–121. doi:10.1037/a0021569. https://doi.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037/a0021569. Retrieved 2020-11-04.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Friedman, Matthew J.; Schnurr, Paula P.; McDonagh-Coyle, Annmarie (1994-06-01). "Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in the Military Veteran" (in en). Psychiatric Clinics of North America. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder 17 (2): 265–277. doi:10.1016/S0193-953X(18)30113-8. ISSN 0193-953X. PMID 7937358. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0193953X18301138.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 10.6 10.7 10.8 Mayo Clinic Staff. "Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) – Symptoms and causes" (in en). https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/post-traumatic-stress-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355967.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 Gimbel, Cynthia; Booth, Alan (1994). "Why Does Military Combat Experience Adversely Affect Marital Relations?". Journal of Marriage and Family 56 (3): 691–703. doi:10.2307/352879. ISSN 0022-2445. https://www.jstor.org/stable/352879.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Cook, Joan; Riggs, David; Thompson, Richard; Coyne, James; Sheikh, Javaid (2004). "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Current Relationship Functioning Among World War II Ex-Prisoners of War.". https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2004-11293-004?errorCode=invalidToken.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Pavalko, Eliza K.; Elder, Glen H. (1990-03-01). "World War II and Divorce: A Life-Course Perspective". American Journal of Sociology 95 (5): 1213–1234. doi:10.1086/229427. ISSN 0002-9602. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/abs/10.1086/229427.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Malone, Johanna C.; Distel, Laura M. L.; Waldinger, Robert J. (2018). "Midlife Ego Development of World War II Veterans: Contributions of Personality Traits and Combat Exposure in Young Adulthood.". in Spiro III, Avron; Settersten Jr., Richard A.; Aldwin, Carolyn M.. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2017-47095-003.

- ↑ Tamoria, Nicholas A.; Alampay, Miguel M.; Santiago, Patcho N. (2015), Ritchie, Elspeth Cameron, ed., "Intimate Relationship Distress and Combat-related Posttraumatic Stress Disorder" (in en), Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Related Diseases in Combat Veterans (Cham: Springer International Publishing): pp. 363–370, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-22985-0_25, ISBN 978-3-319-22985-0, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-22985-0_25, retrieved 2020-11-04

- ↑ DiMauro, Jennifer; Carter, Sarah; Folk, Johanna B.; Kashdan, Todd B. (2014-12-01). "A historical review of trauma-related diagnoses to reconsider the heterogeneity of PTSD" (in en). Journal of Anxiety Disorders 28 (8): 774–786. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.002. ISSN 0887-6185. PMID 25261838. http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0887618514001261.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Madigan, Tim (2015-09-11). "Their war ended 70 years ago. Their trauma didn't." (in en-US). Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/the-greatest-generations-forgotten-trauma/2015/09/11/8978d3b0-46b0-11e5-8ab4-c73967a143d3_story.html.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Mulvey, Stephen (2019-06-07). "The long echo of WW2 trauma" (in en-GB). BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/stories-48528841.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Liehr, Patricia; Nishimura, Chie; Ito, Mio; Wands, Lisa Marie; Takahashi, Ryutaro (2011). "A Lifelong Journey of Moving Beyond Wartime Trauma for Survivors From Hiroshima and Pearl Harbor" (in en-US). Advances in Nursing Science 34 (3): 215–228. doi:10.1097/ANS.0b013e3182272370. ISSN 0161-9268. PMID 21822070. https://dx.doi.org/10.1097%2FANS.0b013e3182272370.

|