Pasch's axiom

In geometry, Pasch's axiom is a statement in plane geometry, used implicitly by Euclid, which cannot be derived from the postulates as Euclid gave them. Its essential role was discovered by Moritz Pasch in 1882.[1]

Statement

The axiom states that,[2]

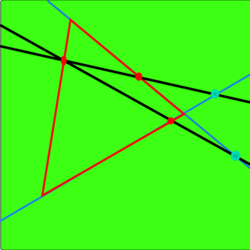

Pasch's axiom — Let A, B, C be three points that do not lie on a line and let a be a line in the plane ABC which does not meet any of the points A, B, C. If the line a passes through a point of the segment AB, it also passes through a point of the segment AC, or through a point of segment BC.

The fact that segments AC and BC are not both intersected by the line a is proved in Supplement I,1, which was written by P. Bernays.[3]

A more modern version of this axiom is as follows:[4]

A more modern version of Pasch's axiom — In the plane, if a line intersects one side of a triangle internally then it intersects precisely one other side internally and the third side externally, if it does not pass through a vertex of the triangle.

(In case the third side is parallel to our line, we count an "intersection at infinity" as external.) A more informal version of the axiom is often seen:

A more informal version of Pasch's axiom — If a line, not passing through any vertex of a triangle, meets one side of the triangle then it meets another side.

History

Pasch published this axiom in 1882,[1] and showed that Euclid's axioms were incomplete. The axiom was part of Pasch's approach to introducing the concept of order into plane geometry.

Equivalences

In other treatments of elementary geometry, using different sets of axioms, Pasch's axiom can be proved as a theorem;[5] it is a consequence of the plane separation axiom when that is taken as one of the axioms. Hilbert uses Pasch's axiom in his axiomatic treatment of Euclidean geometry.[6] Given the remaining axioms in Hilbert's system, it can be shown that Pasch's axiom is logically equivalent to the plane separation axiom.[7]

Hilbert's use of Pasch's axiom

David Hilbert uses Pasch's axiom in his book Foundations of Geometry which provides an axiomatic basis for Euclidean geometry. Depending upon the edition, it is numbered either II.4 or II.5.[6] His statement is given above.

In Hilbert's treatment, this axiom appears in the section concerning axioms of order and is referred to as a plane axiom of order. Since he does not phrase the axiom in terms of the sides of a triangle (considered as lines rather than line segments) there is no need to talk about internal and external intersections of the line a with the sides of the triangle ABC.

Caveats

Pasch's axiom is distinct from Pasch's theorem which is a statement about the order of four points on a line. However, in literature there are many instances where Pasch's axiom is referred to as Pasch's theorem. A notable instance of this is (Greenberg 1974).

Pasch's axiom should not be confused with the Veblen-Young axiom for projective geometry,[8] which may be stated as:

Veblen-Young axiom for projective geometry — If a line intersects two sides of a triangle, then it also intersects the third side.

There is no mention of internal and external intersections in the statement of the Veblen-Young axiom which is only concerned with the incidence property of the lines meeting. In projective geometry the concept of betweeness (required to define internal and external) is not valid and all lines meet (so the issue of parallel lines does not arise).

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Pasch 1912, p. 21

- ↑ This is taken from the Unger translation of the 10th edition of Hilbert's Foundations of Geometry and is numbered II.4.

- ↑ Hilbert 1999, p. 200, the Unger translation.

- ↑ Beutelspacher & Rosenbaum 1998, p. 7

- ↑ Wylie, Jr. 1964, p. 100

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 axiom II.5 in Hilbert's Foundations of Geometry (Townsend translation referenced below), in the authorized English translation of the 10th edition translated by L. Unger (also published by Open Court) it is numbered II.4. There are several differences between these translations.

- ↑ only Hilbert's axioms I.1,2,3 and II.1,2,3 are needed for this. Proof is given in (Faber 1983).

- ↑ Beutelspacher & Rosenbaum 1998, p. 6

References

- Beutelspacher, Albrecht; Rosenbaum, Ute (1998), Projective geometry: from foundations to applications, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48364-3

- Faber, Richard L. (1983), Foundations of Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometry, New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc., ISBN 978-0-8247-1748-3

- Greenberg, Marvin Jay (1974), Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries: Development and History (1st ed.), San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-0454-6

- Greenberg, Marvin Jay (2007), Euclidean and Non-Euclidean Geometries: Development and History (4th ed.), San Francisco: W.H. Freeman, ISBN 978-0-7167-9948-1

- Hilbert, David (1903) (in de), Grundlagen der Geometrie, Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, https://archive.org/details/grunddergeovon00hilbrich

- Hilbert, David (1950), The Foundations of Geometry, LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing, https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17384/17384-pdf.pdf

- Hilbert, David (1999), Foundations of Geometry (2nd ed.), LaSalle, IL: Open Court Publishing, ISBN 978-0-87548-164-7

- Moise, Edwin (1990), Elementary Geometry from an Advanced Standpoint (Third ed.), Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA, p. 74, ISBN 978-0-201-50867-3

- Pambuccian, Victor (2011), "The axiomatics of ordered geometry: I. Ordered incidence spaces.", Expositiones Mathematicae (29): 24–66, doi:10.1016/j.exmath.2010.09.004

- Pasch, Moritz (1912) (in de), Vorlesungen uber neuere Geometrie (2nd ed.), Leipzig: B.G. Teubner, http://quod.lib.umich.edu/cgi/t/text/text-idx?c=umhistmath;idno=ABV7607

- Wylie, Jr., Clarence Raymond (1964), Foundations of Geometry, New York: McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-070-72191-3

- Wylie, Jr., C.R. (2009), Foundations of Geometry, Mineola, New York: Dover Publications, ISBN 978-0-486-47214-0

External links

|