Philosophy:4th century BC philosophy

| It has been suggested that this page be merged into Western philosophy. (Discuss) Proposed since June 2019. |

Philosophy in the 4th century was an epoch which hosted a series of philosophical pioneers and their respective ideologies and edicts. During this time, such individuals as Aristotle (Aristotélēs), Plato (Plátōn) and Socrates (Sōkrátēs) forged the framework of the ideological world that proceeded them and let their own ideals be left to their inheritors. As such their philosophical ideas have left an imprint on the philosophical world as a whole.[1]

Ancient philosophical ideals (such as Aristotelian philosophy) had a creditable influence to the origins of later western philosophy and religious ideals (for example: Judaeo-Christian theology and medieval Islam) during the classical period.[2]

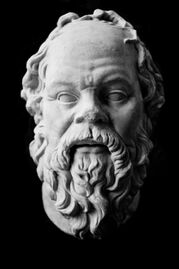

Socrates (Sōkrátēs)

Main article: Socrates

"However his teachings were interpreted, it seems clear that Socrates' main focus was on how to live a good and virtuous life"[1]

Socratic Irony

As defined in the Collins English Dictionary, Socratic Irony is defined as 'a means by which the pretended ignorance of a skilful questioner leads the person answering to expose his or her own ignorance'.[3]

Socratic Irony is categorised as a tradition in the mostly spoken form: the basis of the school of thought is based on knowledge. The philosophical idea is seen as a notable one, since Socrates made use of it on so many occasions, according to his ideological successors, including Plato and Quintilian, noting that: "Socrates's whole life is a game of irony".[4][5]

The teachings of Socrates were mostly spoken, leaving his contemporaries to document the ideologies that had been placed unto them. Plato categorised his mentor's edicts as "the mental equivalent of sleights of hand".[6]

Elenchus (Socratic Method)

The Collins English Dictionary defines Elenchus (or Socratic Method) as the 'refutation of an argument by proving the contrary of its conclusion'.[7]

Most notably, Elenchus was practices by an incarnation of Socrates that was famously portrayed within Plato's own philosophical dramas. However this was neither the term nor activity originated with Plato or his character. Rather it was the historical Socrates who presented it as a philosophical and non-philosophical methodology.[8]

In Parmenides Fragment 7, the definition of Elenchus is told through that of a short story from the perspectives of an unnamed Goddess and a youth (named Parmenides). According to Gary Alan Scott's Does Socrates Have a Method?, in Socrates' work (through Plato) the adaptation of Fragment 7 presents the idea that an argument should be refuted on the basis that an individual is yet to make their own judgement through facts and firsthand experience and, until they do so, Socrates claimed that they 'must resist the pull of a conventional view of what there is—a view gained largely through sense experience and the testimony of others.'[8]

Plato (Plátōn)

Main article: Plato

"Behold! Human beings in an underground den ... like ourselves ... they see only their shadows, or the shadows of one another, which the fire throws on the opposite wall of the cave." - Plato, c379BC [9]

Plato's Cave

In Ben Dupre's, 50 Ideas You Really Need To Know: Philosophy, the allegory of Plato's Cave is summarised as such:

'Imagine you have been imprisoned all your life in a dark cave. Your hands and feet are shackled and your head restrained so that you can only look at the wall straight in front of you. Behind you is a blazing fire, and between you and the fire a walkway on which your captors carry statues and all sorts of objects.The shadows cast on the wall by these objects are the only things you and your fellow prisoners have ever seen, all you have ever thought and talked about.'[10]

The allegory of the Cave is found within the opening of the seventh book of Plato's Republic. The Cave introduces a grouping of four stages of knowledge, where human beings are illustrated as lacking exposure to the outside world. The mind of Plato is accredited with being one of visionary status, through the influence of the Cave on his other philosophical works.[11]

Plato's Cave has garnered other depictions surrounding its meaning, with Alvin B. Kernan noting that 'all the darkness of Plato's cave of illusions would burn away in the bright sun of understanding.'[12]

Philosophical Dramas

As a means of conveying the teachings and philosophies created by himself and his predecessors, Plato created a series of philosophical dramas (or dialogues). Often the leading character in these works was a fictional interpretation of Socrates that acted as Plato's mouth-piece throughout.

The teachings of Plato's dramas/dialogues, Socrates' teachings are reflected in many of Plato's philosophical dramas (Apology, Crito and Euthyphro). Particularly, Euthyphro makes light of the concept of holiness and the presence of strife, in finding a better way (regarding both philosophy and ethics) through a conflict between Plato's incarnation of Socrates, as well as the eponymous character of Euthyphro.[13]

Platonic Love

Plato's theory of Platonic Love, originates from the concept of erôs.[14] Defined in the Oxford Dictionary as '(of love or friendship) intimate and affectionate but not sexual.'[15]

The theory focuses on tiers of love, beauty and power, with the Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy citing that 'Unless it channels its power of love into "higher pursuits," which culminate in the knowledge of the Form of Beauty, erôs is doomed to frustration. For this reason, Plato thinks that most people sadly squander the real power of love by limiting themselves to the mere pleasures of physical beauty.'[16]

Theorising that physical beauty is a shallow layer, Plato's belief was that of a lack of desire. Lydia Amir's study on Plato's philosophy in her work 'Plato's theory of Love: Rationality as Passion', states that 'Love being ephemeral at this stage, the lover will move from one beautiful person to another. Realising that physical beauty is not limited to any one beloved, he will become a lover of all physical beauty.'[17]

Theory of Forms

The theory of forms is a series of concepts and ideals which encompass a range of properties, and, when utilised, Plato's forms represent his perception of his most theoretical reality. The theory maintains that there is two distinct levels of reality: the physical world with which we inhabit and the intelligible World of Forms which stands above our physical world and gives it being. A number of his theoretical forms appear in Plato's "Phaedo".[18]

Plato's Forms are noted as a representation of the mind's innate perception of reality and the information that is available to them. The allegory of the Cave depicts Plato's notion of an innate perception of reality within the closeted parameters of the analogy itself, being described as 'forms that constitute the reality of all things',[19] with the forms occupying the mind and body in tandem alongside this reality.

Immortality and Reincarnation

As defined by the Oxford Dictionary, Immortality denotes 'the ability to live forever; eternal life.'[20] The immortality of the soul is discussed within Plato's dialogue Phaedo, in which he presents several arguments surrounding his theory of immortality, relating to the body and soul, the Argument from Opposites and the Theory of Recollection.[21]

The Cambridge Dictionary defines Reincarnation as 'the belief that a dead person's spirit returns to life in another body.'[22] In his middle dialogues, Plato gave allusions to the concept of reincarnation (transmigration of souls) and the argument that the immortal souls could live on in another life form (featuring in Plato's Phaedo). These ideas did not, however, appear in his earlier works.[14]

Aristotle (Aristotélēs)

"A sense is what has the power of receiving into itself the sensible forms of things without the matter, in the way in which a piece of wax takes on the impress of a signet-ring without the iron or gold"[23][24]

Philosophy of Nature

Aristotle's philosophy of nature is categorised by the notion that nature possesses functions which are controlled by fundamental concepts of motion, space and time.

Motion is separated into several sections:

- motion which affects the substance of a thing, particularly its beginning and its ending;

- motion which brings about changes in quality;

- motion which brings about changes in quantity, by increasing it and decreasing it; and

- motion which brings about locomotion, or change of place. Of these the last is the most fundamental and important.[25]

Aristotle treated the philosophy of nature as a matter of 'general issues like motion, causation, place and time, to systematic explorations and explanations of natural phenomena across different kinds of natural entities.'[26] Within the theory of the philosophy of nature lies the concept of the metaphysical, as entities that are deeply interlinked within the scope of Aristotle's natural philosophy principles, hence the presence of overlap between the two concepts.[26]

Theory of the Soul

As defined by the Cambridge Dictionary, the Soul (or spirit) is 'the spiritual part of a person that some people believe continues to exist in some form after their body has died, or the part of a person that is not physical and experiences deep feelings and emotions.'[27] Aristotle's definition of the soul, however, describes the concept as the perfect expression or realisation of a natural body and is further defined by its growth both through a psychological and physiological process. His concept of a soul relates to the lives of humans, fauna and flora respectively and its very essence is defined by its relationship to an organic structure.[28] Aristotle states that the soul activates or manifests in certain faculties or parts which correspond with natural stages of biological development; there are faculties of nutrition (peculiar to plants), faculties of movement (peculiar to animals) and faculties of reason (peculiar to humans).[29]

Aristotle believed that the soul represented a union between the essences of form and matter. His union and soul theory has been described as furnishing a unified explanatory framework within which all vital functions alike, from metabolism to reasoning, are treated as functions performed by natural organisms of suitable structure and complexity. By this definition, the theory concludes that 'when an organism engages in the relevant activities (e.g., nutrition, movement or thought) it does so in virtue of the system of abilities that is its soul'.[30]

Phainomena and the Endoxic Method

See also: Aristotelianism

“Human beings began to do philosophy,” he says, “even as they do now, because of wonder, at first because they wondered about the strange things right in front of them, and then later, advancing little by little, because they came to find greater things puzzling” (Met. 982b12)[31]

The principles of Phainomena and the Endoxic Method are split as a twin pair, within two separate philosophical entities, as a result of the practical state of their theoretical application.

According to the Oxford Dictionary, Phainomena (now phenomenon) is defined as 'The object of a person's perception.'[32]

The etymology of the word phenomena is based on the 'Late 16th century: via late Latin from Greek phainomenon ‘thing appearing to view’, based on phainein ‘to show’.'[32]

From an etymological standpoint, the roots of Phainomena lie embroiled within a philosophical framework. Its focus on appearances, and being defined as a feature or object within a person's perception of reality, Phainomena works alongside the Endoxic Method, which provides the space for individual perceptions of reality to be formed. Reliant on the Endoxic Method, 'this way we must prove the credible opinions (endoxa) about these sorts of experiences—ideally, all the credible opinions, but if not all, then most of them, those which are the most important.'[31] As such, perceptions of reality are not validated by the opinions crafted by the Endoxic Method, deducing their strength and quality.

The flip side of the philosophical notion is that of the three-staged Endoxic Method. Deriving from the root word Endoxa (meaning 'opinions' or 'beliefs'),[31] the 'Endoxic Method' provides a gateway for the subjective. Aristotle belief was that the subjective should be the tool with which you should mould your first-hand experiences of the world around you.[33]

See also

- Antisthenes

- Archytas

- Aristippus

- Crates of Thebes

- Diogenes

- Metrodorus of Chios

- Pyrrho

- Speusippus

- Theophrastus

- Xenocrates

- Zhuang Zhou

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Socrates". https://www.ancient.eu/socrates/.

- ↑ Delius, Christoph; Gatzemeier, Matthias; Sertcan, Deniz; Wünscher, Kathleen (2013). The Story of Philosophy from Antiquity to Present. China: h.f.ullmann. pp. 6. ISBN 978-3-8480-0428-7. https://www.ullmannmedien.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/leseprobe-geschichte-der-philosophie-gb-hfullmann-978-3-8480-0428-7.pdf.

- ↑ "Socratic irony definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary" (in en). https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/socratic-irony.

- ↑ Vasiliou, Iakovos (2002). "Socrates' reverse irony" (in en). The Classical Quarterly 52 (1): 220–230. doi:10.1093/cq/52.1.220. ISSN 1471-6844.

- ↑ Sedley, David (2008-05-29) (in en). Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy : Volume XXXIV. OUP Oxford. ISBN 9780191562662. https://books.google.com/?id=Y5D67iHp7FwC&pg=PA1&dq=socratic+irony#v=onepage&q=socratic%20irony&f=false.

- ↑ Gellrich, Michelle (1994). "Socratic Magic: Enchantment, Irony, and Persuasion in Plato's Dialogues". The Classical World 87 (4): 275–307. doi:10.2307/4351494. ISSN 0009-8418.

- ↑ "Elenchus definition and meaning | Collins English Dictionary" (in en). https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/elenchus.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Scott, Gary Alan, 1952- (2002). Does Socrates have a method? : rethinking the elenchus in Plato's dialogues and beyond. Pennsylvania State University Press. ISBN 978-0271023472. OCLC 450448705.

- ↑ Dupre, Ben (31 July 2014). 50 Ideas You Really Need to Know: Philosophy. London: Quercus; UK ed. edition (31 July 2014). pp. 8, 9. ISBN 9781848667358.

- ↑ Dupre, Ben (31 July 2014). 50 Ideas You Really Need To Know: Philosophy. London: Quercus. pp. Pg 8. ISBN 9781848667358.

- ↑ Wright, John Henry (1906). "The Origin of Plato's Cave". Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 17: 131–142. doi:10.2307/310313. ISSN 0073-0688.

- ↑ Kernan, Alvin B. (2000-04-10) (in en). In Plato's Cave. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300082678. https://books.google.com/?id=gfdeL4_5IOUC&pg=PR11&dq=plato's+cave#v=onepage&q=plato's%20cave&f=false.

- ↑ Weiss, Roslyn (1994-07-01). Virtue without Knowledge: Socrates' Conception of Holiness in Plato's Euthyphro. doi:10.5840/ancientphil19941422. https://www.pdcnet.org/pdc/bvdb.nsf/purchase?openform&fp=ancientphil&id=ancientphil_1994_0014_0002_0263_0282. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Brickhouse, Thomas. "Plato (427—347 B.C.E.)". https://www.iep.utm.edu/plato/#SH6f.

- ↑ "platonic | Definition of platonic in English by Oxford Dictionaries". https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/platonic.

- ↑ Brickhouse, Thomas. "Plato (427—347 B.C.E.)". https://www.iep.utm.edu/plato/#SH6f.

- ↑ Amir, Lydia (November 2001). "Plato's theory of Love: Rationality as Passion". Practical Philosophy: 9. http://www.society-for-philosophy-in-practice.org/journal/pdf/4-3%2006%20Amir%20-%20Plato%20Love.pdf.

- ↑ "An Introduction to Plato's Theory of Forms" (in en). https://owlcation.com/humanities/An-Introduction-to-Platos-Theory-of-Forms.

- ↑ "Plato and Forms" (in en-US). 2012-04-08. https://www.the-philosophy.com/plato-forms.

- ↑ "immortality | Definition of immortality in English by Oxford Dictionaries". https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/immortality.

- ↑ "Plato: Immortality of the Soul - 1505 Words | Bartleby". https://www.bartleby.com/essay/Plato-Immortality-of-the-Soul-P3TV7CS57KGEY.

- ↑ "REINCARNATION | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary" (in en). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/reincarnation.

- ↑ "Aristotle Quotes" (in en-US). 2012-04-15. https://www.the-philosophy.com/aristotle-quotes.

- ↑ Smith, J.A.. On the Soul (De Anima). http://www.mesacc.edu/~barsp59601/text/philtext/aristotle/soul/bk2/12.html.

- ↑ "Aristotle (384—322 B.C.E.)". https://www.iep.utm.edu/aristotl/.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Bodnar, Istvan (2018), Zalta, Edward N., ed., "Aristotle's Natural Philosophy", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2018/entries/aristotle-natphil/, retrieved 2019-05-14

- ↑ "SOUL | meaning in the Cambridge English Dictionary" (in en). https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/soul.

- ↑ "Aristotle - Philosophy of mind" (in en). https://www.britannica.com/biography/Aristotle.

- ↑ "Aristotle (384—322 B.C.E.)". https://www.iep.utm.edu/aristotl/#H6.

- ↑ Lorenz, Hendrik (2009), Zalta, Edward N., ed., "Ancient Theories of Soul", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2009/entries/ancient-soul/, retrieved 2019-05-14

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Shields, Christopher (2016), Zalta, Edward N., ed., "Aristotle", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University), https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2016/entries/aristotle/, retrieved 2019-05-14

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 "phenomenon | Definition of phenomenon in English by Oxford Dictionaries". https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/phenomenon.

- ↑ "Endoxa" (in en), Wikipedia, 2019-05-05, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Endoxa&oldid=895691079, retrieved 2019-05-14

External links

- Gary Alan Scott (6 March 2002). Does Socrates Have a Method?: Rethinking the Elenchus in Plato's Dialogues and Beyond. Penn State University Press. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-271-03221-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=qEaaCgAAQBAJ&pg=PP1.

- Ben Dupré (31 July 2014). 50 Philosophy Ideas You Really Need to Know. Quercus. ISBN 978-1-84866-735-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=y0KWoAEACAAJ.