Philosophy:Reformist Left

The Reformist Left is a political term coined by Richard Rorty in his 1998 book Achieving Our Country, in reference to the mainstream Left in the United States (though the term may be applied elsewhere) in the first two thirds of the 20th century:

I propose to use the term reformist Left to cover all those Americans who, between 1900 and 1964, struggled within the framework of constitutional democracy to protect the weak from the strong. … I think that the Left should get back into the business of piecemeal reform within the framework of a market economy. This was the business the American Left was in during the first two-thirds of the century. … Emphasizing the continuity between Herbert Croly and Lyndon Johnson, between John Dewey and Martin Luther King, between Eugene Debs and Walter Reuther, would help us to recall a reformist Left which deserves not only respect but imitation—the best model available for the American Left in the coming century.[1]

Definition

Rorty's purpose in defining the Reformist Left is breaking away from the prevailing notion of the Left being divided between New and Old Left, which left no room for anyone but Marxists and Neo-Marxists:

For us Americans, it is important not to let Marxism influence the story we tell about our own Left. We should repudiate the Marxists, insinuation that only those who are convinced capitalism must be overthrown can count as leftists, and that everybody else is a wimpy liberal, a self-deceiving bourgeois reformer. Many recent histories of the Sixties have, unfortunately, been influenced by Marxism. These histories distinguish the emergent student Left and the so-called Old Left from the "liberals"—a term used to cover both the people who administered the New Deal and those whom Kennedy brought from Harvard to the White House in 1961. In such histories, you are counted as a member of the Old Left only if you had proclaimed yourself a socialist early on, and if you continued to express grave doubts about the viability of capitalism. So, in the historiography which has unfortunately become standard, Irving Howe and Michael Harrington count as leftists, but John Kenneth Galbraith and Arthur Schlesinger do not, even though these four men promoted mostly the same causes and thought about our country's problems in pretty much the same terms.[1]

Rorty thus includes in the Reformist Left all that have, at one time or another, advanced reforms—not revolutions—toward social justice:…

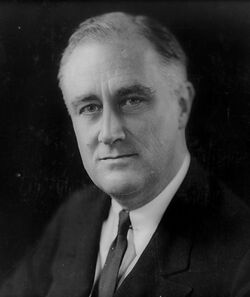

In my sense of the term, Woodrow Wilson—the president who kept Eugene Debs jail but appointed Louis Bradeis to the Supreme Court—counts as a part-time leftist. So does FDR—the president who created the rudiments of a welfare state and urged workers to join labor unions, while obdurately turning his back on African-Americans. So does Lyndon Johnson, who permitted the slaughter of hundreds of thousands of Vietnamese children, but also did more for poor children in the United States than any previous president. … A hundred years from now, Howe and Galbraith, Harrington and Schlesinger, Wilson and Debs, Jane Addams and Angela Davis, Felix Frankfurter and John L. Lewis, W. E. B. Du Bois and Eleanor Roosevelt, Robert Reich and Jesse Jackson, will all be remembered for having advanced the cause of social justice. They will all be seen as having been "on the Left." The difference between these people and men like Calvin Coolidge, Irving Babbitt, T. S. Eliot, Robert Taft, and William Buckley will be far clearer than any of the quarrels which once divided them among themselves.[1]

… while excluding both Marxists…

Marxism was not only a catastrophe for all the countries in which Marxists took power, but a disaster for the reformist Left in all the countries in which they did not. … Leftists should repudiate links with Lenin as firmly as the early Protestants repudiated the doctrine of the Primacy of Peter.[1]

… and Neo-Marxists:

When one of today's academic leftists says that some topic has been "inadequately theorized, " you can be pretty certain that he or she is going to drag in either philosophy of language, or Lacanian psychoanalysis, or some neo-Marxist version of economic determinism. Theorists of the Left think that dissolving political agents into plays of differential subjectivity, or political initiatives into pursuits of Lacan's impossible object of desire, helps to subvert the established order. Such subversion, they say, is accomplished by "problematizing familiar concepts." … With this partial substitution of Freud for Marx as a source of social theory, sadism rather than selfishness has become the principal target of the Left. The heirs of the New Left of the Sixties have created, within the academy, a cultural Left. Many members of this Left specialize in what they call the "politics of difference" or "of identity" or "of recognition." … The new cultural Left which has resulted from these changes has few ties to what remains of the pre-Sixties reformist Left.[1]

History

United States

Birth

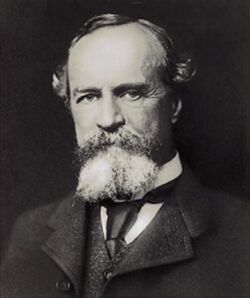

Rorty traces the origins of the Reformist Left in the United States back to William James and Herbert Croly, in their pragmatism, egalitarianism and faith in democracy:

"Democracy, " James wrote, "is a kind of religion, and we are bound not to admit its failure. Faiths and utopias are the noblest exercise of human reason, and no one with a spark of reason in him will sit down fatalistically before the croaker's picture." … Croly wrote that "a more highly socialized democracy is the only practicable substitute on the part of convinced democrats for an excessively individualized democracy." It is time, he believed, to set about developing what he called "a dominant and constructive national purpose." In becoming "responsible for the subordination of the individual to that purpose," he said, "the American state will in effect be making itself responsible for a morally and socially desirable distribution of wealth." From 1909 until the present, the thesis that the state must make itself responsible for such redistribution has marked the dividing line between the American Left and the American Right.[1]

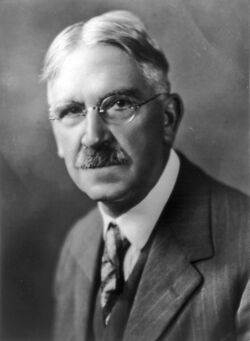

Inspired by James and Croly, Walt Whitman and John Dewey, further fleshed out their call into a vision:

This new, quasi-communitarian rhetoric was at the heart of the Progressive Movement and the New Deal. It set the tone for the American Left during the first six decades of the twentieth century. Walt Whitman and John Dewey, as we shall see, did a great deal to shape this rhetoric. … They offered a new account of what America was, in the hope of mobilizing Americans as political agents. The most striking feature of their redescription of our country is its thoroughgoing secularism. … "Democracy," Dewey said, "is neither a form of government nor a social expediency, but a metaphysic of the relation of man and his experience in nature." For both Whitman and Dewey, the terms "America" and "democracy" are shorthand for a new conception of what it is to be human—a conception which has no room for obedience to a nonhuman authority, and in which nothing save freely achieved consensus among human beings has any authority at all.[1]

And that secularism in Whitman and Dewey, Rorty attributes to Hegel's humanism:

Forgetting about eternity, and replacing knowledge of the antecedently real with hope for the contingent future, is not easy. But both tasks have been a good deal easier since Hegel. Hegel was the first philosopher to take time and finitude as seriously as any Hobbesian materialist, while at the same time taking the religious impulse as seriously as any Hebrew prophet or Christian saint. … He suggested that the meaning of human life is a function of how human history turns out, rather than of the relation of that history to something ahistorical. This suggestion made it easier for two of Hegel's readers, Dewey and Whitman, to claim that the way to think about the significance of the human adventure is to look forward rather than upward: to contrast a possible human future with the human past and present.[1]

Rise

Dewey, in turn, inspired many of the reformers that followed him:

Dewey disliked and distrusted Franklin D. Roosevelt, but many of his ideas came into their own in the New Deal. … Because a lot of my relatives helped write and administer New Deal legislation, I associated leftism with a constant need for new laws and new bureaucratic initiatives which would redistribute the wealth produced by the capitalist system. I spent occasional vacations in Madison with Paul Raushenbush, who ran Wisconsin's unemployment compensation system, and his wife, Elizabeth Brandeis (a professor of labor history, and the author of the first exposé of the misery of migrant workers on Wisconsin farms). Both were students of John R. Commons, who had passed on the heritage of his own teacher, Richard Ely. Their friends included Max Otto, a disciple of Dewey. Otto was the in-house philosopher for a group of Madison bureaucrats and academics clustered around the La Follette family. In that circle, American patriotism, redistributionist economics, anti-communism, and Deweyan pragmatism went together easily and naturally. I think of that circle as typical of the reformist American Left of the first half of the century.[1]

Eclipse

Rorty concurs with Gitlin that the hegemony of reformism within the Left in the United States came to halt in 1964:

The conviction that the vast inequalities within American society could be corrected by using the institutions of a constitutional democracy—that a cooperative commonwealth could be created by electing the right politicians and passing the right laws—held the non-Marxist American Left together from Croly's time until the early 1960s. But the Vietnam War splintered that Left. Todd Gitlin believes August 1964 marks the break in the leftist students' sense of what their country was like. That was the month in which the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party was denied seats at the Democratic Convention in Atlantic City, and in which Congress passed the Tonkin Gulf Resolution.

Gitlin argues plausibly that these two events "fatefully turned the movement" and "drew a sharp line through the New Left's Sixties." Before them, most of the New Left's rhetoric was consensual and reformist. After them, it began to build up to the full-throated calls for revolution with which the decade ended. Whether or not one agrees with Gitlin about the exact date, it is certainly the case that the mid-Sixties saw the beginning of the end of a tradition of leftist reformism which dated back to the Progressive Era. …

The New Leftists gradually became convinced that the, Vietnam War, and the endless humiliation inflicted on African-Americans, were clues to something deeply wrong with their country, and not just mistakes correctable by reforms. They wanted to hear that America was a very different sort of place, a much worse place, than their parents and teachers had told them it was. So they responded enthusiastically to Lasch's claim that "the structure of American society makes it almost impossible for criticism of existing policies to become part of political discourse. The language of American politics increasingly resembles an Orwellian monologue."

When they read in Lasch's book that "the United States of the mid-twentieth century might better be described as an empire than as a community," the students felt justified in giving up their parents' hope that reformist politics could cope with the injustice they saw around them. Lasch's book made it easy to stop thinking of oneself as a member of a community, as a citizen with civic responsibilities. For if you turn out to be living in an evil empire (rather than, as you had been told, a democracy fighting an evil empire), then you have no responsibility to your country; you are accountable only to humanity. If what your government and your teachers are saying is all part of the same Orwellian monologue if the differences between the Harvard faculty and the military-industrial complex, or between Lyndon Johnson and Barry Goldwater, are negligible then you have a responsibility to make a revolution.[1]

Trump's election

Rorty's 1998 book was widely quoted in the mainstream and alternative media for its prophetic warnings materialised in the United States' 2016 presidential election:[2][3][4][5][6][7][8]

At that point, something will crack. The nonsuburban electorate will decide that the system has failed and start looking around for a strongman to vote for—someone willing to assure them that, once he is elected, the smug bureaucrats, tricky lawyers, overpaid bond salesmen, and postmodernist professors will no longer be calling the shots. A scenario like that of Sinclair Lewis' novel It Can 't Happen Here may then be played out. For once such a strongman takes of office, nobody can predict what will happen. In 1932, most of the predictions made about what would happen if Hindenburg named Hitler chancellor were wildly overoptimistic.

One thing that is very likely to happen is that the gains made in the past forty years by black and brown Americans, and by homosexuals, will be wiped out. Jocular contempt for women will come back into fashion. The words "nigger" and "kike" will once again be heard in the workplace. All the sadism which the academic Left has tried to make unacceptable to its students will come flooding back. All the resentment which badly educated Americans feel about having their manners dictated to them by college graduates will find an outlet.

But such a renewal of sadism will not alter the effects of selfishness. For after my imagined strongman takes charge, he will quickly make his peace with the international super rich, just as Hitler made his with the German industrialists. He will invoke the glorious memory of the Gulf War to provoke military adventures which will generate short-term prosperity. He will be a disaster for the country and the world. People will wonder why there was so little resistance to his evitable rise. Where, they will ask, was the American Left? Why was it only rightists like Buchanan who spoke to the workers about the consequences of globalization? Why could not the Left channel the mounting rage of the newly dispossessed?[1]

Revival

Rorty's book, more than simply a historical and philosophical account of the Reformist Left, is itself a manifesto toward its revival:

I think that the Left should get back into the business of piecemeal reform within the framework of a market economy. This was the business the American Left was in during the first two-thirds of the century. … I can sum up by saying that it would be a good thing if the next generation of American leftists found as little resonance in the names of Karl Marx and Vladimir Ilyich Lenin as in those of Herbert Spencer and Benito Mussolini. It would be an even better thing if the names of Ely and Croly, Dreiser and Debs, A. Philip Randolph and John L. Lewis were more familiar to these leftists than they were to the students of the Sixties. … Emphasizing the continuity between Herbert Croly and Lyndon Johnson, between John Dewey and Martin Luther King, between Eugene Debs and Walter Reuther, would help us to recall a reformist Left which deserves not only respect but imitation—the best model available for the American Left in the coming century.[1]

Outside the United States

While Rorty focuses his definition of the Reformist Left in the realm of the American Left, his characterization sits in a much larger narrative, extending far beyond the confines of the United States:

| Author | Life | Title | Year | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adam Smith | 1723–1790 | The Theory of Moral Sentiments[9] | 1761 | |

| Louis Blanc | 1811–1882 | The Organisation of Labor[10] | 1839 | |

| John Stuart Mill | 1806–1873 | Principles of Political Economy[11] | 1848 | |

| Walt Whitman | 1819–1892 | Democratic Vistas[12] | 1871 | |

| Henry George | 1839–1897 | Progress and Poverty[13] | 1879 | |

| Ernest Renan | 1823–1892 | What is a Nation?[14] | 1882 | |

| Pope Leo XIII | 1810–1893 | Rerum novarum[15] | 1891 | |

| Eduard Bernstein | 1850–1932 | Evolutionary Socialism[16] | 1899 | |

| Jane Addams | 1860–1935 | Democracy and Social Ethics[17] | 1902 | |

| Lizzie Magie | 1866–1948 | The Landlord's Game | 1903 | |

| William James | 1842–1910 | Pragmatism[18] | 1907 | |

| Benedetto Croce | 1866–1952 | Philosophy of the Practical: Economic and Ethic[19] | 1908 | |

| Herbert Croly | 1869–1930 | The Promise of American Life[20] | 1909 | |

| David Lloyd George | 1863–1945 | People's Budget[21] | 1909 | |

| Leonard Hobhouse | 1864–1929 | Liberalism[22] | 1911 | |

| Hilaire Belloc | 1870–1953 | The Servile State[23] | 1912 | |

| Woodrow Wilson | 1856–1924 | The New Freedom | 1913 | |

| Louis Brandeis | 1856–1941 | Other People's Money and How the Bankers Use It[24] | 1914 | |

| Franz Oppenheimer | 1864–1943 | The State[25] | 1914 | |

| Eugene V. Debs | 1855–1926 | Labor and Freedom[26] | 1916 | |

| G. K. Chesterton | 1874–1936 | Utopia of Usurers[27] | 1917 | |

| John Dewey | 1859–1952 | The Public and its Problems[28] | 1927 | |

| Felix Frankfurter | 1882–1965 | A Critical Analysis for Lawyers and Laymen | 1927 | |

| Carlo Rosselli | 1899–1937 | Liberal Socialism[29] | 1930 | |

| Pope Pius XI | 1857–1939 | Quadragesimo anno | 1931 | |

| R. H. Tawney | 1880–1962 | Equality | 1931 | |

| Aldous Huxley | 1894–1963 | Brave New World[30] | 1932 | |

| Oszkár Jászi | 1875–1957 | Proposed Roads to Peace | 1932 | |

| Michal Kalecki | 1899–1970 | A Theory of the Business Cycle[31] | 1933 | |

| Eleanor Roosevelt | 1884–1962 | The State’s Responsibility for Fair Working Conditions[32] | 1933 | |

| John Maynard Keynes | 1883–1946 | The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money[33] | 1935 | |

| W. E. B. Du Bois | 1868–1893 | Black Reconstruction in America[34] | 1935 | |

| Oskar Lange | 1904–1965 | On the Economic Theory of Socialism | 1936 | |

| John L. Lewis | 1880–1969 | The Rights of Labor[35] | 1937 | |

| Nicholas Kaldor | 1908–1986 | A Model of the Trade Cycle[36] | 1940 | |

| Abba P. Lerner | 1903–1982 | Functional Finance and the Federal Debt | 1943 | |

| William Beveridge | 1879–1963 | Full Employment in a Free Society[37] | 1944 | |

| Franklin Delano Roosevelt | 1882–1945 | Second Bill of Rights | 1944 | |

| Karl Polanyi | 1886–1964 | The Great Transformation | 1944 | |

| John Dedman | 1896–1973 | Full Employment in Australia | 1945 | |

| George Orwell | 1903–1950 | Nineteen Eighty-Four | 1948 | |

| Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. | 1917–2007 | The Vital Center | 1949 | |

| Alberto Pasqualini | 1901–1960 | The Essence of Laborism | 1950 | |

| H. C. Coombs | 1906–1997 | Economic Development and Financial Stability | 1955 | |

| Joan Robinson | 1903–1983 | The Accumulation of Capital | 1956 | |

| Ludwig Erhard | 1897–1977 | Prosperity Through Competition | 1958 | |

| John Kenneth Galbraith | 1908–2006 | The Affluent Society | 1958 | |

| Piero Sraffa | 1898–1983 | Producing Commodities with Commodities | 1960 | |

| Michael Harrington | 1928–1989 | The Other America: Poverty in the United States | 1962 | |

| Pope John XXIII | 1881–1963 | Mater et magistra | 1961 | |

| Martin Luther King, Jr. | 1929–1968 | Where do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? | 1967 | |

| Pope Paul VI | 1897–1978 | Populorum progressio | 1967 | |

| Axel Leijonhufvud | b. 1933 | On Keynesian Economics and the Economics of Keynes[38] | 1968 | |

| Bayard Rustin | 1912–1987 | The Anatomy of Frustration | 1968 | |

| John Rawls | 1921–2002 | A Theory of Justice[39] | 1971 | |

| Paul Davidson | b. 1930 | Money and the Real World[40] | 1972 | |

| Jan Kregel | b. 1944 | The Theory of Capital | 1976 | |

| Ted Kennedy | 1932–2009 | The Dream Will Never Die | 1980 | |

| Pope John Paul II | 1920–2005 | Laborem exercens | 1981 | |

| Willy Brandt | 1913–1992 | Left and Free | 1982 | |

| Mario Cuomo | 1932–2015 | Tale of Two Cities | 1984 | |

| Peter Navarro | b. 1949 | The Policy Game | 1984 | |

| Hyman Minsky | 1919–1996 | Stabilizing an Unstable Economy[41] | 1986 | |

| Robert Dimand | The Origins of the Keynesian Revolution | 1988 | ||

| Philip Harvey | Securing the Right to Employment | 1989 | ||

| William Vickrey | 1914–1996 | Full Employment without Increased Inflation | 1992 | |

| Robert Skidelsky | b. 1939 | The World After Communism | 1995 | |

| Geoff Harcourt | b. 1931 | Capitalism, Socialism and Post-Keynesianism | 1995 | |

| Warren Mosler | b. 1949 | Full Employment and Price Stability | 1997 | |

| L. Randall Wray | b. 1953 | Government as Employer of Last Resort | 1997 | |

| Richard Rorty | 1931–2007 | Achieving Our Country[42] | 1998 | |

| Stephanie Kelton | b. 1969 | The Hierarchy of Money | 1998 | |

| Mathew Forstater | Functional Finance and Full Employment | 1999 | ||

| James K. Galbraith | b. 1952 | Created Unequal[43] | 2000 | |

| Peter A. Diamond | b. 1940 | Towards an Optimal Social Security Design | 2001 | |

| Ha-Joon Chang | b. 1963 | Kicking Away the Ladder[44] | 2002 | |

| Joseph Stiglitz | b. 1943 | Globalization and Its Discontents | 2003 | |

| Steven Pinker | b. 1954 | The Blank Slate[45] | 2003 | |

| Pavlina R. Tcherneva | Full Employment and Price Stability[46] | 2004 | ||

| Jeffrey Sachs | b. 1954 | The End of Poverty[47] | 2005 | |

| Ellen Brown | b. 1945 | Web of Debt[48] | 2007 | |

| Bill Mitchell | b. 1952 | Full Employment Abandoned | 2008 | |

| Roberto Mangabeira Unger | b. 1947 | The Left Alternative[49] | 2009 | |

| Eric Tymoigne | Central Banking, Asset Prices and Financial Fragility | 2009 | ||

| Scott T. Fullwiler | Modern Monetary Theory | 2010 | ||

| Abhijit Banerjee & Esther Duflo | b. 1961; b. 1972 | Poor Economics | 2011 | |

| Emmanuel Saez | b. 1972 | The Case for a Progressive Tax | 2011 | |

| Thomas Piketty | b. 1971 | Capital in the Twenty-First Century | 2013 | |

| Mariana Mazzucato | b. 1968 | The Entrepreneurial State[50] | 2013 | |

| Miles Corak | Income Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility[51] | 2013 | ||

| Pope Francis | b. 1936 | Evangelii gaudium | 2013 | |

| Luiz Carlos Bresser-Pereira | b. 1934 | New Developmentalism | 2014 | |

| Raj Chetty | b. 1979 | Behavioral Economics and Public Policy | 2015 | |

| Mark Blyth | b. 1967 | Austerity[52] | 2015 | |

| Robert Reich | b. 1946 | Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few[53] | 2015 | |

| Thomas Frank | b. 1965 | Listen, Liberal[54] | 2016 |

References

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Rorty, Richard (1998) (in en). Achieving Our Country: Leftist Thought in Twentieth-century America. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674003118. https://books.google.com/books/about/Achieving_Our_Country.html?id=uyLF5Wm2_IcC.

- ↑ Hedges, Chris (2016-03-02). "The Revenge of the Lower Classes and the Rise of American Fascism" (in en-US). Truthdig. http://www.truthdig.com/report/item/the_revenge_of_the_lower_classes_and_the_rise_of_american_fascism_20160302.

- ↑ Senior, Jennifer (2016-11-20). "Richard Rorty’s 1998 Book Suggested Election 2016 Was Coming" (in en-US). The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/11/21/books/richard-rortys-1998-book-suggested-election-2016-was-coming.html.

- ↑ Helmore, Edward (2016-11-19). "'Something will crack': supposed prophecy of Donald Trump goes viral" (in en). https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/nov/19/donald-trump-us-election-prediction-richard-rorty.

- ↑ "Richard Rorty’s prescient warnings for the American left". Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2017/2/9/14543938/donald-trump-richard-rorty-election-liberalism-conservatives.

- ↑ "A Book Written in 1998 Predicted Trump’s Election Win in a Scary-Accurate Way" (in en-US). Cosmopolitan. 2016-11-21. https://www.cosmopolitan.com/politics/a8349320/richard-rorty-book-predicted-donald-trump-win/.

- ↑ Mathis-Lilley, Ben (2016-11-11). "The Philosopher Who Predicted Trump in 1998 Also Predicted His First Act as President-Elect" (in en-US). Slate. ISSN 1091-2339. http://www.slate.com/blogs/the_slatest/2016/11/11/richard_rorty_predicted_election_of_trump_like_figure_election_in_1998.html.

- ↑ "Douglas Todd: Liberals lose their own game of identity politics" (in en-US). Vancouver Sun. 2016-12-16. http://vancouversun.com/opinion/columnists/douglas-todd-liberals-lose-their-own-game-of-identity-politics.

- ↑ Adam Smith (1761) (in English). The Theory of Moral Sentiments. University of Lausanne. printed for A. Millar. https://archive.org/details/theorymoralsent08smitgoog.

- ↑ Louis Blanc (1848) (in French). Organisation du travail par Louis Blanc. National Central Library of Florence. Meline. https://archive.org/details/bub_gb__-crBhxwieQC.

- ↑ Mill, John Stuart (1909). Principles of political economy, with some of their applications to social philosophy. Robarts - University of Toronto. London, Longmans, Green. https://archive.org/details/principlesofpoli00milluoft.

- ↑ Whitman, Walt (1871). Democratic vistas. University of California Libraries. Washington, D. C. https://archive.org/details/democraticvista00whitrich.

- ↑ George, Henry (1884). Progress and poverty: an inquiry into causes of industrial depressions, and of increase of want with increase of wealth. The remedy. Kelly - University of Toronto. London : W. Reeves. https://archive.org/details/progresspovertyi00georuoft.

- ↑ Renan, Ernest (1882) (in French). Qu'est-ce qu'une nation?: conférence faite en Sorbonne, le 11 mars 1882. Oxford University. Lévy. https://archive.org/details/questcequunenat00renagoog.

- ↑ Pope Leo XIII (May 15, 1891). "Rerum Novarum". http://w2.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/en/encyclicals/documents/hf_l-xiii_enc_15051891_rerum-novarum.html.

- ↑ Bernstein, Eduard (1961). Evolutionary socialism: a criticism and affirmation. University of Connecticut Libraries. New York, Schocken Books. https://archive.org/details/evolutionarysocia00bern.

- ↑ Jane Addams (1902) (in English). Democracy and Social Ethics. Harvard University. Macmillan. https://archive.org/details/democracyandsoc04addagoog.

- ↑ James, William (1907). Pragmatism, a new name for some old ways of thinking; popular lectures on philosophy. University of California Libraries. New York, [etc.] : Longmans, Green, and Co.. https://archive.org/details/pragmatismnewnam00jame.

- ↑ Croce, Benedetto; Ainslie, Douglas (1913). Philosophy of the practical : economic and ethic. Robarts - University of Toronto. London : Macmillan and Co. https://archive.org/details/philosophyofthep00crocuoft.

- ↑ Croly, Herbert David (1909). The promise of American life. Robarts - University of Toronto. New York, MacMillan. https://archive.org/details/promiseofamerica00crol.

- ↑ Lloyd George, David (1909). The people's budget. Robarts - University of Toronto. London : Hodder & Stoughton. https://archive.org/details/peoplesbudget00lloy.

- ↑ Hobhouse, L. T. (Leonard Trelawney) (1919). Liberalism. University of California Libraries. London : Williams & Norgate. https://archive.org/details/liberalism00hobh.

- ↑ Belloc, Hilaire (1912). The servile state. University of California Libraries. London & Edinburgh : T. N. Foulis. https://archive.org/details/servilestate00belliala.

- ↑ Brandeis, Louis Dembitz (1914). Other people's money, and how the bankers use it. University of California Libraries. New York : Stokes. https://archive.org/details/otherpeoplesmone00bran.

- ↑ Oppenheimer, Franz; Gitterman, John M. (John Milton) (1922). The state, its history and development viewed sociologically. University of California Libraries. New York : B.W. Huebsch. https://archive.org/details/stateitshistoryd00oppe.

- ↑ Debs, Eugene V. (1855–1926) (1916). Labor and Freedom (1916). https://archive.org/details/16DebsLaborandfreedom.

- ↑ Chesterton, G. K. (Gilbert Keith) (1917). Utopia of usurers, and other essays. University of California Libraries. New York : Boni and Liveright. https://archive.org/details/utopiaofusurerso00ches.

- ↑ 1859-1952., Dewey, John, (2002). Obshchestvo i ego problemy. Moskva: Idei︠a︡-Press. ISBN 5733300523. OCLC 50484200. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/50484200.

- ↑ Rosselli, Carlo (1994) (in en). Liberal Socialism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691025605. https://books.google.com.au/books/about/Liberal_Socialism.html?id=N_iCQgAACAAJ&source=kp_book_description&redir_esc=y.

- ↑ 1894-1963., Huxley, Aldous, ([20]03). Brave new world ([Nachdr.] ed.). New York: Perennial Classics. ISBN 0060929871. OCLC 917264987. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/917264987.

- ↑ Kalecki, Michal (1937). "A Theory of the Business Cycle". The Review of Economic Studies 4 (2): 77–97. doi:10.2307/2967606. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2967606.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Eleanor (March 1933). "The State’s Responsibility for Fair Working Conditions". Scribner’s Magazine.

- ↑ 1883-1946., Keynes, John Maynard, (2008). The general theory of employment, interest and money. [Miami]: BN Publishing. ISBN 9789650060251. OCLC 505231981. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/505231981.

- ↑ B., Du Bois, W. E. (℗2018), Black reconstruction in America, Lewis, David Levering., Willis, Mirron., Blackstone Audio, Inc., Blackstone Audio, ISBN 9781538521816, OCLC 1029245735, https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/1029245735, retrieved 2018-10-18

- ↑ "The Rights of Labor - John L. Lewis 1937". http://www.emersonkent.com/speeches/the_rights_of_labor.htm.

- ↑ Kaldor, Nicholas (1940). "A Model of the Trade Cycle". The Economic Journal 50 (197): 78–92. doi:10.2307/2225740. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2225740.

- ↑ William, Beveridge, (2015). Full ermployment in a free society a report. London: Routledge. ISBN 9781138830240. OCLC 931786964. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/931786964.

- ↑ Axel., Leijonhufvud, (1968). On Keynesian economics and the economics of Keynes : a study in monetary theory. New York [etc.]: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195009487. OCLC 780471203. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/780471203.

- ↑ 1921-2002., Rawls, John, (1979). Eine Theorie der Gerechtsgkeit (1. Aufl ed.). Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp. ISBN 3518278711. OCLC 34697822. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/34697822.

- ↑ 1930-, Davidson, Paul, (1978). Money and the real world (2nd ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0333235185. OCLC 4082945. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/4082945.

- ↑ P., Minsky, Hyman (2008). Stabilizing an unstable economy. Yale University Press.. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780071592994. OCLC 438046474. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/438046474.

- ↑ Richard., Rorty, (1998). Achieving our country : leftist thought in twentieth-century America. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 067400311X. OCLC 37864000. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/37864000.

- ↑ K., Galbraith, James (2000). Created unequal : the crisis in American pay (University of Chicago Press ed.). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226278794. OCLC 44270519. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/44270519.

- ↑ Ha-Joon., Chang, (2002). Kicking away the ladder : development strategy in historical perspective. London: Anthem. ISBN 1843310279. OCLC 48931308. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/48931308.

- ↑ 1954-, Pinker, Steven,, The blank slate : the modern denial of human nature, Bevine, Victor,, ISBN 9781480563254, OCLC 868720808, https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/868720808, retrieved 2018-10-18

- ↑ 1914-, Vickrey, William S. (William Spencer), (2004). Full employment and price stability : the macroeconomic vision of William S. Vickrey. Forstater, Mathew, 1961-, Tcherneva, Pavlina R., 1974-. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. ISBN 1843764091. OCLC 55744360. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/55744360.

- ↑ Jeffrey., Sachs, (2005). The end of poverty : economic possibilities for our time. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 1594200459. OCLC 57243168. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/57243168.

- ↑ Hodgson., Brown, Ellen (2012). Web of debt : the shocking truth about our money system and how we can break free (5th., rev. and updated ed.). Baton Rouge, La.: Third Millennium Press. ISBN 9780983330851. OCLC 778886199. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/778886199.

- ↑ Mangabeira., Unger, Roberto (2009). The left alternative. Unger, Roberto Mangabeira.. London: Verso. ISBN 9781844673704. OCLC 461614755. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/461614755.

- ↑ 1968-, Mazzucato, Mariana,. The entrepreneurial state : debunking public vs. private sector myths (Revised ed.). London. ISBN 9780857282521. OCLC 841672270. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/841672270.

- ↑ Corak, Miles (2013-08). "Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility" (in en). Journal of Economic Perspectives 27 (3): 79–102. doi:10.1257/jep.27.3.79. ISSN 0895-3309. https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/jep.27.3.79.

- ↑ Blyth, Mark (2013-05-23) (in en). Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. OUP USA. ISBN 9780199828302. https://books.google.com/books/about/Austerity.html?id=9lQkpnALnWAC.

- ↑ Reich, Robert B. (2015) (in en). Saving Capitalism: For the Many, Not the Few. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9780385350570. https://books.google.com/books/about/Saving_Capitalism.html?id=ezXaCwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Frank, Thomas (2016-03-15) (in en). Listen, Liberal: Or, What Ever Happened to the Party of the People?. Metropolitan Books. ISBN 9781627795401. https://books.google.com/books/about/Listen_Liberal.html?id=yj1BCgAAQBAJ.