Philosophy:Shibui

Shibui (渋い) (adjective), shibumi (渋み) (noun), or shibusa (渋さ) (noun) are Japanese words that refer to a particular aesthetic of simple, subtle, and unobtrusive beauty.[1] Like other Japanese aesthetics terms, such as iki and wabi-sabi, shibui can apply to a wide variety of subjects, not just art or fashion.[2]

Shibusa is an enriched, subdued appearance or experience of intrinsically fine quality with economy of form, line, and effort, producing a timeless tranquility. Shibusa includes the following essential qualities:

- Shibui objects appear to be simple overall, but they include subtle details, such as textures, that balance simplicity with complexity.

- This balance of simplicity and complexity ensures that one does not tire of a shibui object, but constantly finds new meanings and enriched beauty that cause its aesthetic value to grow over the years.[3]

- Shibusa walks a fine line between contrasting aesthetic concepts such as elegant and rough or spontaneous and restrained.[4]

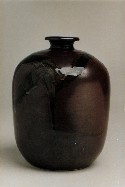

Color is given more to meditation than to spectacle. Understated, not innocent. Subdued colors, muddied with gray tones create a silvery effect. (Shibuichi is a billon metal alloy with a silver-gray appearance.) In interior decorating and painting, gray is added to primary colors to create a silvery effect that ties different colors together in a coordinated scheme. Depending on how much gray is added, shibui colors range from pastels to dark. Brown, black, and soft white are preferred. Quiet monochromes and sparse subdued design provide a somber serenity with a hint of sparkle. Occasionally, a patch of bright color is added as a highlight.

Definition

Shibusa is not to be confused with wabi or sabi. Although many wabi or sabi objects are shibui, not all shibui objects are wabi or sabi. Wabi or sabi objects can be more severe and sometimes exaggerate intentional imperfections to such an extent that they may appear to be artificial. Shibui objects are not necessarily imperfect or asymmetrical, although they can include these qualities.

The seven elements of shibusa are simplicity, implicity, modesty, naturalness, everydayness, imperfection, and silence. They are adapted from the concepts authored by Dr. Yanagi Sōetsu (1898–1961), aesthetician and museum curator, published in the Japanese magazine Kōgei (journal) (ja) between 1930 and 1940. The aristocratic simplicity of shibusa is the refined expression of the essence of elements in an aesthetic experience producing quietude. Spare elegance is evident in darkling serenity with a hint of sparkle. Implicity allows depth of feeling to be visible through spare surface design thereby manifesting the invisible core that offers new meanings with each encounter. The person of shibui modesty exalts excellence via taking time to learn, watch, read, understand, develop, think, and merges into understatement and silence concerning oneself. Naturalness conveys spontaneity in unforced growth. Shibusa freedom is maintained in healthy roughness of texture and irregular asymmetrical form wherein the center lies beyond all particular things, in infinity. Everydayness raises ordinary things to a place of honor, void of all artificial and unnecessary properties, thus imparting spiritual joy—for today is more auspicious than tomorrow. Everydayness provides a framework, a tradition for an artist's oeuvre to be a unit not a process. Hiroshi Mizuo argues that the best examples of shibusa are found in the crafts, ordinary objects made for everyday use. They tend to be more spontaneous and healthy than many of the fine arts. Imperfection is illustrated in Nathaniel Hawthorne's gothic novel, The Marble Faun. The chapter "An Aesthetic Company" mentions some ragged and ill-conditioned antique drawings and their attributions and virtues.

The aroma and fragrance of new thought were perceptible in these designs, after three centuries of wear and tear. The charm lay partly in their very imperfection; for this is suggestive and sets the imagination at work.

Yanagi Sōetsu, in The Unknown Craftsman, refers to the imperfection in shibusa as "beauty with inner implications".[5] Creation here means making a piece that will lead the viewer to draw beauty from it for oneself. Shibui beauty in the tea ceremony is in the artistry of the viewer.

Shibusa's sanctuary of silence is non-dualism—the resolution of opposites. Its foundation is intuition coupled with faith and beauty revealing phases of truth and the worship and reverence for life.

In James A. Michener's book Iberia the adjective shibui is referenced as follows: "The Japanese have a word which summarizes all the best in Japanese life, yet it has no explanation and cannot be translated. It is the word shibui, and the best approximation to its meaning is 'acerbic good taste'." The author Trevanian (the nom de plume of Dr. Rodney William Whitaker) wrote in his 1979 best-selling novel, Shibumi, "Shibumi has to do with great refinement underlying commonplace appearances." In the business fable The Shibumi Strategy, the author, Matthew E. May, wrote that shibumi "has come to denote those things that exhibit in paradox and all at once the very best of everything and nothing: Elegant simplicity. Effortless effectiveness. Understated excellence. Beautiful imperfection."

Shibui, a registration or "felt sense" of evolving perfection. What is being registered is the "life" behind the qualities of any experience. A felt sense of qualities, such as, quiet beauty with intelligence, love, light, and joy. These qualities can be more easily registered when quietly viewing simple, natural, everyday phenomenon or objects, such as a sunrise or a simple piece of pottery. Shibui can sometimes be more easily registered by two people in a meditative state (quiet in their emotions and their minds) while viewing the same phenomenon or object. For example, when viewing the same sunset or piece of art, subconsciously, both people register the qualities of the life or implicity underlying the experience or object; this registration of the underlying life precipitates into the conscious as registering something extraordinary in the everyday ordinary. If you both register, then looking into the other person's eyes, you understand that you both shared the same phenomenon, a knowing of the underlying life, or at least the qualities of that underlying life. The qualities registered can seem paradoxical. Complex experiences or objects seem simple; perfection is found in imperfection. All objects and experiences, both everyday and extraordinary, can have a beauty, a quiet purposeful intent, a cool, matter of fact underlying joy.

Potters, musicians, painters, bonsai, and other artists often work to bring in shibui-like qualities into their art. A few go behind these qualities to bring the underlying "life" into their art. Expert singers, actors, potters, and artists of all other sorts were often said to be shibui; their expertise caused them to do things beautifully without making them excessive or gaudy. Today, sometimes baseball players are even said to be shibui when they contribute to the overall success of the team without doing anything to make themselves stand out individually. The apparent effortlessness displayed by athletes such as tennis player Roger Federer and hockey great Wayne Gretzky are examples of shibumi in personal performance. Shibui, and its underlying life, is found in all art and in everything around us—including ourselves. Taking the path to understand and experience shibui, is a step toward understanding and consciously registering the life underlying all.

History of the term

Originating in the Muromachi period (1336–1573) as shibushi, the term originally referred to a sour or astringent taste, such as that of an unripe persimmon.[1] Shibui still maintains this literal meaning, and remains the antonym of amai (甘い), meaning "sweet".

However, by the beginnings of the Edo period (1615–1868), the term gradually had begun to refer to a pleasing aesthetic. The people of Edo expressed their tastes in using this term to refer to anything from song to fashion to craftsmanship that was beautiful by being understated, or by being precisely what it was meant to be and not elaborated upon. Essentially, the aesthetic ideal of shibumi seeks out events, performances, people, or objects that are beautiful in a direct and simple way, without being flashy.

The Unknown Craftsman, a selection of art critic Yanagi Sōetsu's work translated by potter Bernard Leach, discusses shibumi.[6]

The concept of shibui was introduced to the West in the Elizabeth Gordon-edited August and September 1960 issues of the American magazine House Beautiful, subtitled "Discover shibui, the word for the highest level in beauty" and "How to be shibui with American things" respectively.[7]

References

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Dr. Mazhar Hussain; Robert Wilkinson (2006). The Pursuit of Comparative Aesthetics: An Interface Between East and West. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.. pp. 227–8. ISBN 978-0-7546-5345-5. https://books.google.com/books?id=1Wez4pgWp3AC&pg=PA227.

- ↑ De Garis (5 September 2013). We Japanese. Routledge. p. 15. ISBN 978-1-136-18367-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=hUm0AAAAQBAJ&pg=PA15.

- ↑ Sunamita Lim (2007). Japanese Style: Designing with Nature's Beauty. Gibbs Smith. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4236-0092-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=NsWemDyPlE4C&pg=PA41.

- ↑ Takie Sugiyama Lebra (1976). Japanese Patterns of Behaviour. University of Hawaii Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-8248-0460-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=JWG07rhiyUMC&pg=PA20.

- ↑ Yanagi, Muneyoshi (1972). The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty. Tokyo: Kodansha International. p. 124. OCLC 1311141932. https://archive.org/details/unknowncraftsman0000yana/page/124/mode/2up.

- ↑ Yanagi, Muneyoshi (1972). The Unknown Craftsman: A Japanese Insight into Beauty. Tokyo: Kodansha International. p. 147–151. OCLC 1311141932. https://archive.org/details/unknowncraftsman0000yana/page/147/mode/2up.

- ↑ House Beautiful cover images.

Sources

- Gropius,Walter; Tange, Kenzo; Ishimoto, Yasuhiro (1960), Katsura. New Haven, Connecticut:Yale University Press. ISBN 978-1-904313-59-5

- "Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan". Tokyo, 1993 Japan: An Illustrated Encyclopedia. "Shibui," page 1361. ISBN 978-0-02-897203-9

- Leach, Bernard (1976) A Potter's Book. London:Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-10973-9

- Lee, Sherman E. (1982)Far Eastern Art, page 476. New York:Prentice-Hall Abrams. ISBN 0-8109-3414-0

- May, Matthew E. (2011) The Shibumi Strategy. San Francisco, CA. Jossey-Bass. ISBN 978-0-470-89214-5

- Michener, James A. (1968), Iberia, (Spanish Travels and Reflections). A Fawcett Crest Book reprinted by arrangement with Random House, Inc. ISBN 0-449-20733-1

- Mizuo, Hiroshi (1970), "Toyo no Bigaku" (Oriental Aesthetics). Tokyo, Japan. Bijutsu sensho. OCLC 502035618

- Peterson, Susan (1974), Shoji Hamada: A Potter's Way and Work. Kodansha International – Harper & Row. ISBN 978-1-57498-198-8

- Richie, Donald (2007) A Tractate on Japanese Aesthetics, Berkeley, CA. Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-23-5

- Sartwell, Crispin (2004) Six Names of Beauty, New York, NY. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-96558-6

- Tanizaki, Junichiro (1977)In Praise of Shadows, Sedgwick, ME. Leete's Island Books. ISBN 978-0-918172-02-0.

- Theodore, Constance Rodman (1993), "Shibusa and the Iron Glaze Ware of Dorothy Bearnson", University of Utah: Master of Arts thesis for Professor P. Lennox Tierney. ISBN 978-1-57498-198-8

- Theodore, Constance Rodman (2012), Shibusa USA: Beginner's Checklist. ISBN 978-1-62620-788-2

- Trevanian (1979), Shibumi, New York: Crown Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-517-53243-3

- Ueda, Makoto (1985), "Shibui", Kodansha Encyclopedia of Japan. Tokyo: Kodansha Ltd. ISBN 978-0-87011-620-9

- Waters, Mary Yukari (2003), The Laws of Evening, 'Shibusa', New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-7432-4332-3

- Wildenhain, Marguerite (1973), The Invisible Core: A Potter's Life and Thoughts. Palo Alto, California:Pacific Books. ISBN 978-0-87015-201-6

- Yanagi, Soetsu (1966) "Mystery of Beauty" lecture, The Archie Bray Foundation, Helena, Montana.

- Yanagi, Soetsu (1972) The Unknown Craftsman- Japanese Insight into Beauty. Kodansha International Ltd. ISBN 0-87011-948-6

- Yanagi, Soetsu (1953) "The Way of Tea" lecture, Honolulu Academy of Arts, Honolulu, Hawaii.

- Young, David Earl (1965), "The Origin and Influence of the Concept of Shibusa in Japan", University of Hawaii:Master of Arts thesis. CB5.H3 no.645

- Young, David E. & Young, Michiko Kimura (2008), http://www.japaneseaesthetics.com.

- Young, David E. & Young, Michiko Kimura (2012), Spontaneity in Japanese Art and Culture, Gabriola, British Columbia, Canada:Coastal Tides Press ISBN 978-0-9881110-1-1