Philosophy:The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters

| The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters | |

|---|---|

| Spanish: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos | |

| |

| Artist | Francisco Goya |

| Year | c. 1799 |

| Type | Etching, aquatint, drypoint and burin |

| Dimensions | 21.5 cm × 15 cm (8 7⁄16 in × 5 7⁄8 in) |

| Location | Various print rooms have a print from the first edition. The one illustrated is at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.[1] |

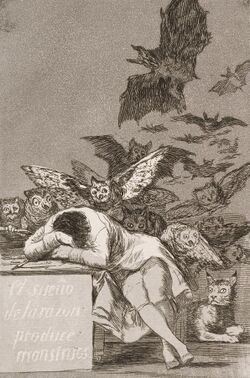

The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters or The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters (Spanish: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos) is an aquatint by the Spanish painter and printmaker Francisco Goya. Created between 1797 and 1799 for the Diario de Madrid,[2][3] it is the 43rd of the 80 aquatints making up the satirical Los caprichos.

Subject

Los Caprichos is a series of 80 etchings published in 1799 wherein Goya criticized the rampant political, social, and religious abuses of the time period. In this series of etchings, Goya heavily utilized the popular technique of caricature, which he enriched with artistic innovation. Goya’s usage of the recently-developed technique of aquatint (i.e., a method of etching a printing plate so that tones similar to watercolor washes can be reproduced[4]) gave Los Caprichos pronounced tonal effects and spirited contrast that made them a major achievement in the history of engraving.

Of the 80 aquatints, number 43, "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters", can be viewed as Goya’s personal manifesto; many observers believe that Goya intended to depict himself asleep amidst his drawing tools, his reason dulled by slumber, bedeviled by creatures that prowl in the dark. Such creatures that appear in this work are often associated in Spanish folk tradition with mystery and evil; the owls surrounding Goya may be symbols of folly, and the swarming bats may symbolize ignorance. The title of the print, as marked on the front of the desk, is typically read as a proclamation of Goya’s adherence to the values of the Enlightenment: without reason, evil and corruption prevail.[5] Goya also included a caption for this print that may suggest a slightly different interpretation: "Imagination abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters; united with her, she is the mother of the arts and source of their wonders". This implies that Goya believed that imagination should never be completely renounced in favor of the strictly rational, as imagination (in combination with reason) is what produces works of artistic innovation.[2]

Implied in Goya's preparatory inscription, the artist's nightmare reflects his view of Spanish society, which he portrayed in the Caprichos as demented, corrupt, and ripe for ridicule.

The full epigraph for Capricho No. 43 reads; "Fantasy abandoned by reason produces impossible monsters: united with her [reason], she [fantasy] is the mother of the arts and the origin of their marvels."

Goya and satire

Goya's print has sometimes been interpreted in the context of satire.[6] During the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century in Spain, Goya's paintings and etchings combined artistic innovation with social criticism to create visually-satirical works. Goya created numerous portraits of Spanish royalty that were quite realistic, and completed these portraits with jarring social commentary that marked a departure from the practice of painting royal figures with sensational opulence and splendor.[7]

Los Caprichos, Goya's set of 80 aquatints that were published in the year 1799, revealed and emphasized the innumerable flaws that human beings inherently possess. The series of works as a whole deals with the uniquely-human vices of "...vanity, greed, superstition, promiscuity and delusion".[8] Particularly, 'The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters' exhibits (quite literally) the treacherous lengths of human irrationality, and the implications of excessive illogicality without the counterbalance of reason. The remainder of the aquatints featured in Los Caprichos incorporated contentious subjects including marriage, prostitution, the law, and the Church; some of these works featured specific and targeted political satire, implying Goya's dismay at the developments of Spanish political life. Goya supplemented these works with caustic and sardonic captions, augmenting the overall satirical effect.

Goya's stylistic progression up to Los Caprichos

Goya’s artistic career was initially marked by his creation of artwork for the Spanish royalty; Goya was called to Madrid to produce preliminary paintings in the form of tapestry cartoons for the Royal Tapestry Factory of Santa Barbara (Real Fábrica de Tapices de Santa Bárbara). Goya began to produce oil-on-canvas cartoon paintings from which tapestries for the royal palaces could be made. According to many relevant sources of the time period, Goya displayed extraordinary skill in painting tapestry cartoons, and his talent apparently warranted the attention of the Neoclassical painter Anton Raphael Mengs. Some of the preliminary paintings he completed in Madrid included a series of nine hunting scenes for the dining room at the Royal Monastery of San Lorenzo del Escorial (located in the municipality of San Lorenzo del Escorial near Madrid), as well as a series of ten cartoons for tapestries in the dining room of the Royal Palace of El Pardo.[9]

As Goya continued to engage with members of the aristocracy, he was met with an increasing quantity of royal patronage and received commissions at a higher frequency. Between the years of 1785 and 1788, Goya created works that depicted executives and their families from the Bank of San Carlos (el Banco Nacional de San Carlos) in Spain. In 1786, Goya was appointed the official painter to King Charles III, and in 1789 he was promoted to Court Painter under Charles IV (1788–1808) who had recently ascended to the throne.[10]

In the year 1792, Goya contracted an illness that left him permanently deaf; historians are unsure what the precise illness was that he suffered from, but it is speculated that Goya contracted either lead poisoning or “colic of Madrid” (a metal poisoning produced by cooking utensils), or some form of palsy. This illness caused him to suffer from an inability to balance on his feet, temporary blindness, and permanent deafness, which profoundly affected his life and his artistic style. In the years following his going deaf, Goya spent much of his time isolated from the outside world, as he asserted that he was unable to resume his work on large tapestry cartoons, and thus he turned to more personal projects.[11] During this time, he studied the events and philosophies of the French Revolution, and created a series of etchings portraying the inherent vices and cruelties of human nature in a more pessimistic and sardonic style for which he would later become known. This series of prints, namely Los Caprichos, were published in 1799 and depicted the confines of human reason, featuring whimsical and fantastical creatures that invade the mind during dreams, as displayed in 'The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters' (El Sueño de la Razón Produce Monstruos).[9]

During the year 1799, Goya was promoted by the Spanish crown to the position of First Court Painter, and spent the next two years working on a portrait of the family of Charles IV. In 1801, Goya published Charles IV of Spain and His Family, an oil painting that displays Charles IV of Spain and his family. Influenced by Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas, Goya painted the royal family in the foreground and himself in the background at an easel. This painting was shocking as it was very detailed and naturalistic; critics widely believed that the painting was meant as a criticism of the royal family as the members of the family were portrayed in a physically-unflattering manner.[9]

Goya and the Enlightenment

Goya’s Los Caprichos echo key themes of the Enlightenment, particularly the prioritization of freedom and expression over custom and tradition, and the emphasis on knowledge and intellect over ignorance. Goya’s The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters presents a similar concept; this work praises reason as a work of imagination, such that it is on the basis of the imagination that reason "sleeps", and the abundance of imagination with an absence of reasoning and logic may produce "monsters".[2] One of the work’s critics writes, "[The animals] symbolize the world’s 'vulgar prejudices' and 'harmful ideas commonly believed'. Goya, borrowing the penetrating vision of the lynx, intended to expose them to light by depicting them so that we can recognize and fight them, perpetuating the solid testimony of the truth... When we are asleep we do not see, nor can we denounce, the monsters of ignorance and vice."[12] This interpretation of The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters reflects the ideals of the Enlightenment by denouncing ignorance and highlighting the importance of awareness.

This conventional interpretation of this plate--an endorsement of Enlightenment ideology, translating sueño as "sleep" rather than the equally justifiable translation as "dream"--remains for the most part silent about motives for its placement in the center of the series. Interpreted as The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Plate 43 might have made an ideal frontispiece for the plates to follow in the first half, as humans beings do exhibit monstrous behavior without using "reason." This would then be a usual Enlightenment criticism of society. By placing Plate 43 in the middle, as it is, what follows in the second half is also an Enlightenment criticism of society--but a very dark satire of the first half. It is the Enlightenment gone mad, run amok; it begins with The Dream of Reason Produces Monsters.[13] John J. Ciofalo has written: "Truly, however, placing it in the middle made its meaning unmistakable and unleashed in Los Caprichos a potent, even explosive, narrative power...the gateway from the "dream" of reason into the nightmare of reason, indeed, of madness."[14] Goya turns the light of the Enlightenment back on itself and here are where the monsters are found.

Preparatory drawings

On the preparatory drawings for The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters, Goya explained (in reference to the artist that is depicted asleep), "His only purpose is to banish harmful, vulgar beliefs, and to perpetuate in this work of caprices the solid testimony of truth." Art historian Philip Hofer has suggested on the evidence of one of the preparatory sketches that Goya had intended for this work to be the frontispiece of Los Caprichos, but Goya ultimately opted for The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters to be the 43rd etching out of the 80 total.[15] This work apparently provides a transition from the first half of Los Caprichos, which includes more elements related to the vices of humanity, whereas the second half of the series introduces more fantastical creatures such as witches and goblins. Philip Hofer posits that the illustration on a title page of one of Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s volumes influenced Goya’s composition in this work, but that Goya ultimately decided not to display this as the frontispiece because it would seem speculative in a political sense[15] (i.e., Rousseau’s Social Contract Theory that all men were born free heavily contributed to the French Revolution). Art historians relate The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters to historical events that occurred after its publication, such as the World Wars and the Holocaust, that represented an utter lack of reason "...on a modern industrial scale, all condemning our unwitting slumber".[15]

Technical aspects

Los Caprichos is notable for its use of aquatint, a printing technique that falls under the category of intaglio printing. Intaglio printing is characterized by the artist applying ink to the grooves of the matrix (i.e., the surface from which a print is made), allowing for intricate lines and refined tonality. According to William M. Ivins Jr., the first official Curator of Prints at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, "every intaglio print in which the lines are laid in a formal manner is an engraving, and every one in which they are laid freely is an etching,"[16] thus clarifying that the series Los Caprichos falls under the broad category of "etchings". To produce an aquatint, the image itself is formed by applying a layer of resin (or a substitute of asphalt or bitumen) using one of two technical methods. An artist may allow the resin to settle on the plate as a dry dust by inserting the printing plate at the bottom of a box wherein the dust has been distributed. The printing plate is then heated so that each grain of resin dust melts and adheres to the metal. The alternative method is to dissolve the resin or asphalt in alcohol, and then pour this solution over the printing plate. The alcohol will then evaporate, leaving a thin film of resin which will dry on the plate. The plate is then immersed in acid, which etches the metal in the gaps around the grains of resin. The dust is then cleaned off the plate, to which ink is applied; the ink penetrates the etched depressions, and when the plate is printed, it creates a network of thin etched lines. This process produces a single tone, but the density of the tone varies depending on how finely the dust was ground and how thickly it covered the plate.[16]

See also

- List of works by Francisco Goya

References

- ↑ "The sleep of reason produces monsters (No. 43)". https://art.nelson-atkins.org/objects/24528/the-sleep-of-reason-produces-monsters-no-43. art.nelson-atkins.org.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Nehamas, Alexander (2001). "The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters". Representations 74 (Spring): 37–54. doi:10.1525/rep.2001.74.1.37.

- ↑ "Goya - The Sleep of Reason". Eeweems.com. http://eeweems.com/goya/sleep_of_reason.html.

- ↑ "Definition of AQUATINT" (in en). https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/aquatint.

- ↑ Tal, Guy (2010-03-26). "The gestural language in Francisco Goya's Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters". Word & Image 26 (2): 115–127. doi:10.1080/02666280902843647. ISSN 0266-6286. https://doi.org/10.1080/02666280902843647.

- ↑ Blum, Paul von (2003). "Satire" (in en). doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T076124. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000076124.

- ↑ "The Family of Charles IV, 1800 by Francisco Goya". https://www.franciscogoya.com/the-family-of-charles-iv.jsp.

- ↑ Hartley, Craig (2003). "Aquatint" (in en). doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T003495. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000003495.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Muller, Priscilla E. (2003). "Goya (y Lucientes), Francisco (José) de" (in en). doi:10.1093/gao/9781884446054.article.T033882. https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000033882.

- ↑ Voorhies, James (October 2003). "Francisco de Goya (1746–1828) and the Spanish Enlightenment". https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/goya/hd_goya.htm.

- ↑ "Goya y Lucientes, Francisco de - The Collection - Museo Nacional del Prado". https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/artist/goya-y-lucientes-francisco-de/39568a17-81b5-4d6f-84fa-12db60780812?searchMeta=goya.

- ↑ Goya, Francisco, 1746–1828 (1989). Goya and the spirit of enlightenment. Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E., Sayre, Eleanor A., Museo del Prado., Museum of Fine Arts, Boston., Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.). Boston: Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 0-87846-300-3. OCLC 19336840. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/19336840.

- ↑ Ciofalo, John J. (2001). The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 81. ISBN 0-521-77136-6. OCLC 43561897. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/43561897.

- ↑ Ciofalo, John J. (2001). The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 81. ISBN 0-521-77136-6. OCLC 43561897. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/43561897.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Procter, Kenneth J. (2007). "Strange, Weird, and Fantastical Drawings". American Artist: Drawing 4: 54–63.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Ivins Jr., William M. (1987). How Prints Look. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. pp. 46–48. ISBN 0807066478.

External links

- Schaefer, Sarah C. Goya's The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters . smARThistory. Khan Academy.

- Nyu.edu, The Sleep of Reason

|