Philosophy:Twentieth-century English literature

This article is focused on English-language literature rather than the literature of England, so that it includes writers from Scotland, Wales, and the whole of Ireland, as well as literature in English from former British colonies. It also includes, to some extent, the United States, though the main article for that is American literature.

Modernism is a major literary movement of the first part of the twentieth-century. The term Postmodern literature is used to describe certain tendencies in post-World War II literature.

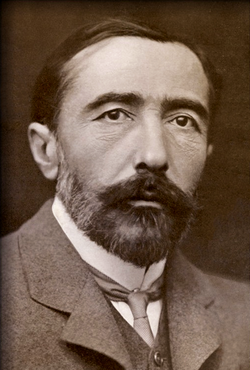

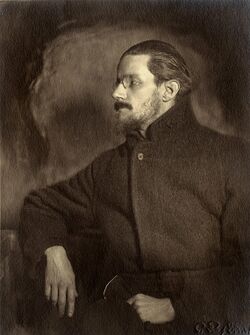

Irish writers were especially important in the twentieth-century, including James Joyce and later Samuel Beckett, both central figures in the Modernist movement. Americans, like poets T. S. Eliot and Ezra Pound and novelist William Faulkner, were other important modernists. British modernists include Joseph Conrad, E. M. Forster, Dorothy Richardson, Virginia Woolf, and D. H. Lawrence. In the mid-twentieth-century major writers started to appear in the various countries of the British Commonwealth, including several Nobel laureates.

1901–22 modernism

In the early 20th-century literary modernism developed in the English-speaking world due to a general sense of disillusionment with the Victorian era attitudes of certainty, conservatism, and belief in the idea of objective truth.[1] The movement was influenced by the ideas of Charles Darwin (1809–82) (On Origin of Species) (1859), Ernst Mach (1838–1916), Henri Bergson (1859–1941), Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900), James G. Frazer (1854–1941), Karl Marx (1818–83) (Das Kapital, 1867), and the psychoanalytic theories of Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), among others.[2] The continental art movements of Impressionism, and later Cubism, were also important inspirations for modernist writers.[3] Important literary precursors of modernism, were: Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821–81) (Crime and Punishment (1866), The Brothers Karamazov (1880); Walt Whitman (1819–92) (Leaves of Grass) (1855–91); Charles Baudelaire (1821–67) (Les Fleurs du mal), Rimbaud (1854–91) (Illuminations, 1874); August Strindberg (1849–1912), especially his later plays.[4]

A major British lyric poet of the first decades of the 20th century was Thomas Hardy (1840–1928). Though not a modernist, Hardy was an important transitional figure between the Victorian era and the 20th century. A major novelist of the late 19th century, Hardy, after the adverse criticism of his last novel, Jude the Obscure, concentrated on publishing poetry. On the other hand, another significant transitional figure between Victorians and modernists, the late-19th-century novelist, Henry James (1843–1916), continued to publish major works into the 20th century. James, born in the US, lived in Europe from 1875, and became a British citizen in 1915.[5] Another immigrant, Polish-born modernist novelist Joseph Conrad (1857–1924) published his first important work, Heart of Darkness, in 1899 and Lord Jim in 1900. The American exponent of Naturalism Theodore Dreiser's (1871–1945) Sister Carrie was also published in 1900.

Poetry

However, the Victorian Gerard Manley Hopkins's (1844–89) highly original poetry was not published until 1918, long after his death, while the career of another major modernist poet, Irishman W. B. Yeats (1865–1939), began late in the Victorian era. Yeats was one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of both the Irish and British literary establishments, in his later years he served as an Irish Senator for two terms. Yeats was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival. In 1923 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, the first Irishman so honoured.[6] Yeats is generally considered [by whom?] one of the few writers who completed their greatest works after being awarded the Nobel Prize: these works include The Tower (1928) and The Winding Stair and Other Poems (1929).[7]

In addition to W. B. Yeats other important early modernist poets were the American poets T. S. Eliot (1888–1965) and Ezra Pound (1885–1972). Eliot became a British citizen in 1927 but was born and educated in America. His most famous works are: "Prufrock" (1915), The Waste Land (1921) and Four Quartets (1935–42). Ezra Pound was not only a major poet, first publishing part of The Cantos in 1917, but an important mentor for other poets, most significantly in his editorial advice for Eliot's poem The Waste Land.[8] Other important American poets writing early in the 20th century were William Carlos Williams (1883–1963), Robert Frost (1874–1963), who published his first collection in England in 1913, and H.D. (1886–1961). Gertrude Stein (1874–1946), an American expatriate living in Paris, famous for her line "Rose is a rose is a rose is a rose," was also an important literary force during this time period. American poet Marianne Moore (1887–1972) published from the 1920s to the 1960s.

But while modernism was to become an important literary movement in the early decades of the new century, there were also many fine writers who, like Thomas Hardy, were not modernists. During the early decades of the 20th century the Georgian poets like Rupert Brooke (1887–1915), Walter de la Mare (1873–1956), and John Masefield (1878–1967, Poet Laureate from 1930) maintained a conservative approach to poetry by combining romanticism, sentimentality and hedonism, sandwiched as they were between the Victorian era, with its strict classicism, and Modernism, with its strident rejection of pure aestheticism. Edward Thomas (1878–1917) is sometimes treated as another Georgian poet.[9] Thomas enlisted in 1915 and is one of the First World War poets along with Wilfred Owen (1893–1918), Rupert Brooke (1887–1915), Isaac Rosenberg (1890–1917), Edmund Blunden (1896–1974) and Siegfried Sassoon (1886–1967).

Drama

Irish playwrights George Bernard Shaw (1856–1950) and J.M. Synge (1871–1909) were influential in British drama. Shaw's career began in the last decade of the 19th century, while Synge's plays belong to the first decade of the 20th century. Synge's most famous play, The Playboy of the Western World, "caused outrage and riots when it was first performed" in Dublin in 1907.[10] George Bernard Shaw turned the Edwardian theatre into an arena for debate about important political and social issues, like marriage, class, "the morality of armaments and war" and the rights of women.[11] An important dramatist in the 1920s, and later, was Irishman Seán O'Casey (1880–1964). Also in the 1920s and later Noël Coward (1899–1973) achieved enduring success as a playwright, publishing more than 50 plays from his teens onwards. Many of his works, such as Hay Fever (1925), Private Lives (1930), Design for Living (1932), Present Laughter (1942) and Blithe Spirit (1941), have remained in the regular theatre repertoire.

Novelists

Amongst the novelists, after Joseph Conrad, other important early modernists include Dorothy Richardson (1873–1957), whose novel Pointed Roof (1915), is one of the earliest example of the stream of consciousness technique, and D. H. Lawrence (1885–1930), who published The Rainbow in 1915, though it was immediately seized by the police.[12] Then in 1922 Irishman James Joyce's important modernist novel Ulysses appeared. Ulysses has been called "a demonstration and summation of the entire movement".[13] Set during one day in Dublin, in it Joyce creates parallels with Homer's epic poem the Odyssey. William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury (1929) is another significant modernist novel, that uses the stream of consciousness technique.

Novelists who are not considered modernists include: Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936) who was also a successful poet; H. G. Wells (1866–1946); John Galsworthy (1867–1933), (Nobel Prize in Literature, 1932) whose works include a sequence of novels, collectively called The Forsyte Saga (1906–21); Arnold Bennett (1867–1931) author of The Old Wives' Tale (1908); G. K. Chesterton (1874–1936); and E.M. Forster's (1879–1970), though Forster's work is "frequently regarded as containing both modernist and Victorian elements".[14] H. G. Wells was a prolific author who is now best known for his science fiction novels,[15] most notably The War of the Worlds, The Time Machine, The Invisible Man and The Island of Doctor Moreau all written in the 1890s. Other novels include Kipps (1905) and Mr Polly (1910). Forster's most famous work, A Passage to India 1924, reflected challenges to imperialism, while his earlier novels, such as A Room with a View (1908) and Howards End (1910), examined the restrictions and hypocrisy of Edwardian society in England.

Another major work of science fiction, from the early 20th century, is A Voyage to Arcturus by Scottish writer David Lindsay, first published in 1920. It combines fantasy, philosophy, and science fiction in an exploration of the nature of good and evil and their relationship with existence. It has been described by writer Colin Wilson as the "greatest novel of the twentieth century",[16] and was a central influence on C. S. Lewis's Space Trilogy.[17]

The most popular British writer of the early years of the 20th century was arguably Rudyard Kipling, a highly versatile writer of novels, short stories and poems, and to date the youngest ever recipient of the Nobel Prize for Literature (1907). Kipling's works include The Jungle Books (1894–95), The Man Who Would Be King and Kim (1901), while his inspirational poem "If—" (1895) is a national favourite and a memorable evocation of Victorian stoicism. Kipling's reputation declined during his lifetime, but more recently postcolonial studies has "rekindled an intense interest in his work, viewing it as both symptomatic and critical of imperialist attitudes".[18] Strongly influenced by his Christian faith, G. K. Chesterton was a prolific and hugely influential writer with a diverse output. His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown, who appeared only in short stories, while The Man Who Was Thursday published in 1908 is arguably his best-known novel. Of his nonfiction, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906) was largely responsible for creating a popular revival for Dickens's work as well as a serious reconsideration of Dickens by scholars.[19]

Modernism in the 1920s and 1930s

The modernist movement continued through the 1920s and 1930s and beyond. During the period between the World Wars, American drama came to maturity, thanks in large part to the works of Eugene O'Neill (1888–1953). O'Neill's experiments with theatrical form and his use of both Naturalist and Expressionist techniques had a major influence on American dramatists. His best-known plays include Anna Christie (Pulitzer Prize 1922), Desire Under the Elms (1924), Strange Interlude (Pulitzer Prize 1928), Mourning Becomes Electra (1931). In poetry Hart Crane published The Bridge in 1930 and E. E. Cummings and Wallace Stevens were publishing from the 1920s until the 1950s. Similarly William Faulkner continued to publish until the 1950s and was awarded a Nobel Prize in 1949. However, not all those writing in these years were modernists; among the writers outside the movement were American novelists Theodore Dreiser, Dos Passos, Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald (The Great Gatsby 1925), and John Steinbeck.

Important British writers between the World Wars, include the Scottish poet Hugh MacDiarmid (1892–1978), who began publishing in the 1920s, and novelists Virginia Woolf (1882–1941), E. M. Forster (1879–1970) (A Passage to India, 1924), Evelyn Waugh (1903–1966), Graham Greene (1904–1991), Anthony Powell (1905–2000), P. G. Wodehouse (1881–1975) (who was not a modernist) and D. H. Lawrence. Lawrence's Lady Chatterley's Lover was published privately in Florence in 1928, though the unexpurgated version was not published in Britain until 1959.[8] Woolf was an influential feminist, and a major stylistic innovator associated with the stream-of-consciousness technique in novels like Mrs Dalloway (1925) and To the Lighthouse (1927). Her 1929 essay A Room of One's Own contains her famous dictum "A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write fiction".[20]

In the 1930s W. H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood co-authored verse dramas, of which The Ascent of F6 (1936) is the most notable, that owed much to Bertolt Brecht. T. S. Eliot had begun this attempt to revive poetic drama with Sweeney Agonistes in 1932, and this was followed by The Rock (1934), Murder in the Cathedral (1935) and Family Reunion (1939). There were three further plays after the war. In Parenthesis, a modernist epic poem by David Jones (1895–1974) first published in 1937, is probably the best known contribution from Wales to the literature of the First World War.[citation needed]

An important development, beginning in the 1930s and 1940s was a tradition of working class novels actually written by working-class background writers. Among these were coal miner Jack Jones, James Hanley, whose father was a stoker and who also went to sea as a young man, and coal miners Lewis Jones from South Wales and Harold Heslop from County Durham.[citation needed]

Aldous Huxley (1894–1963) published his famous dystopia Brave New World in 1932, the same year as John Cowper Powys's A Glastonbury Romance. Henry Miller's Tropic of Cancer then appeared in 1934, though it was banned for many years in both Britain and America.[21] Samuel Beckett (1906–89) published his first major work, the novel Murphy in 1938. This same year Graham Greene's (1904–91) first major novel Brighton Rock was published. Then in 1939 James Joyce's published Finnegans Wake, in which he creates a special language to express the consciousness of a dreaming character.[22] It was also in 1939 that another Irish modernist poet, W. B. Yeats, died. British poet W. H. Auden was another significant modernist in the 1930s.

1940 to 2000

Though some have seen modernism ending by around 1939,[23] with regard to English literature, "When (if) modernism petered out and postmodernism began has been contested almost as hotly as when the transition from Victorianism to modernism occurred".[24] In fact a number of modernists were still living and publishing in the 1950s and 1960, including T. S. Eliot, William Faulkner, Dorothy Richardson, and Ezra Pound. Furthermore, Basil Bunting (1900–1985) published little until Briggflatts in 1965 and Samuel Beckett, born in Ireland in 1906, continued to produce significant works until the 1980s, including Waiting for Godot (1953), Happy Days (1961), Rockaby (1981), though some view him as a post-modernist.[25]

Among British writers in the 1940s and 1950s were novelists Graham Greene and Anthony Powell, whose works span the 1930s to the 1980s and poet Dylan Thomas, while Evelyn Waugh, and W. H. Auden continued publishing significant work.

The novel

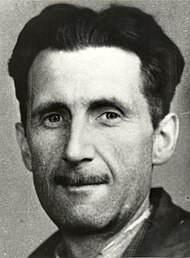

In 1947 Malcolm Lowry published Under the Volcano, while George Orwell's dystopia of totalitarianism, 1984, was published in 1949. One of the most influential novels of the immediate post-war period was William Cooper's naturalistic Scenes from Provincial Life, a conscious rejection of the modernist tradition.[26] Graham Greene was a convert to Catholicism and his novels explore the ambivalent moral and political issues of the modern world. Notable for an ability to combine serious literary acclaim with broad popularity, his novels include Brighton Rock (1938), The Power and the Glory (1940), The Heart of the Matter (1948), A Burnt-Out Case (1961), and The Human Factor (1978). Other novelists writing in the 1950s and later were: Anthony Powell whose twelve-volume cycle of novels A Dance to the Music of Time, is a comic examination of movements and manners, power and passivity in English political, cultural and military life in the mid-20th century; comic novelist Kingsley Amis (1922–1995) is best known for his academic satire Lucky Jim (1954); Nobel Prize laureate William Golding's allegorical novel Lord of the Flies 1954, explores how culture created by man fails, using as an example a group of British schoolboys marooned on a deserted island who try to govern themselves, but with disastrous results. Philosopher Iris Murdoch was a prolific writer of novels throughout the second half of the 20th century, that deal especially with sexual relationships, morality, and the power of the unconscious, including Under the Net (1954), The Black Prince (1973) and The Green Knight (1993). Scottish writer Muriel Spark pushed the boundaries of realism in her novels. Her first, The Comforters (1957) concerns a woman who becomes aware that she is a character in a novel; The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie (1961), at times takes the reader briefly into the distant future, to see the various fates that befall its characters. Anthony Burgess is especially remembered for his dystopian novel A Clockwork Orange (1962), set in the not-too-distant future, which was made into a film by Stanley Kubrick in 1971. In the entirely different genre of Gothic fantasy Mervyn Peake (1911–1968) published his highly successful Gormenghast trilogy between 1946 and 1959.

One of Penguin Books' most successful publications in the 1970s was Richard Adams's heroic fantasy Watership Down (1972). Evoking epic themes, it recounts the odyssey of a group of rabbits seeking to establish a new home. Another successful novel of the same era was John Fowles' The French Lieutenant's Woman (1969), with a narrator who freely admits the fictive nature of his story, and its famous alternative endings. This was made into a film in 1981 with a screenplay by Harold Pinter. Angela Carter (1940–1992) was a novelist and journalist, known for her feminist, magical realism, and picaresque works. Her novels include, The Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman 1972 and Nights at the Circus 1984. Margaret Drabble (born 1939) is a novelist, biographer and critic, who published from the 1960s into the 21st century. Her older sister, A. S. Byatt (born 1936) is best known for Possession published in 1990.

Martin Amis (born 1949) is one of the most prominent of contemporary British novelists. His best-known novels are Money (1984) and London Fields (1989). Pat Barker (born 1943) has won many awards for her fiction. English novelist and screenwriter Ian McEwan (born 1948) is another of contemporary Britain's most highly regarded writers. His works include The Cement Garden (1978) and Enduring Love (1997), which was made into a film. In 1998 McEwan won the Man Booker Prize with Amsterdam. Atonement (2001) was made into an Oscar-winning film. McEwan was awarded the Jerusalem Prize in 2011. Zadie Smith's Whitbread Book Award winning novel White Teeth (2000), mixes pathos and humour, focusing on the later lives of two war time friends in London. Julian Barnes (born 1946) is another successful living novelist, who won the 2011 Man Booker Prize for his book The Sense of an Ending, while three of his earlier books were shortlisted for the Booker Prize: Flaubert's Parrot (1984), England, England (1998), and Arthur & George (2005). He has also written crime fiction under the pseudonym Dan Kavanagh.[27]

Two significant contemporary Irish novelists are John Banville (born 1945) and Colm Tóibín (born 1955). Banville is also an adapter of dramas, a screenwriter,[28] and a writer of detective novels under the pseudonym Benjamin Black. Banville has won numerous awards: The Book of Evidence was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and won the Guinness Peat Aviation award in 1989; his eighteenth novel, The Sea, won the Booker Prize in 2005; he was awarded the Franz Kafka Prize in 2011. Colm Tóibín (Irish, 1955) is a novelist, short story writer, essayist, playwright, journalist, critic, and, most recently, poet.

Scotland has in the late 20th century produced several important novelists, including James Kelman, who like Samuel Beckett can create humour out of the most grim situations. How Late it Was, How Late, 1994, won the Booker Prize that year; A. L. Kennedy's 2007 novel Day was named Book of the Year in the Costa Book Awards.[29] In 2007 she won the Austrian State Prize for European Literature;[30] Alasdair Gray's Lanark: A Life in Four Books (1981) is a dystopian fantasy set in a surreal version of Glasgow called Unthank.[31]

Drama

An important cultural movement in the British theatre which developed in the late 1950s and early 1960s was Kitchen sink realism (or "kitchen sink drama"), a term coined to describe art (the term itself derives from an expressionist painting by John Bratby), novels, film and television plays. The term angry young men was often applied [by whom?] to members of this artistic movement. It used a style of social realism which depicts the domestic lives of the working class, to explore social issues and political issues. The drawing room plays of the post war period, typical of dramatists like Terence Rattigan and Noël Coward were challenged in the 1950s by these Angry Young Men, in plays like John Osborne's Look Back in Anger (1956). Arnold Wesker and Nell Dunn also brought social concerns to the stage.[citation needed]

Again in the 1950s, the absurdist play Waiting for Godot (1955) (originally En attendant Godot, 1952), by Irish writer Samuel Beckett profoundly affected British drama. The Theatre of the Absurd influenced Harold Pinter (1930–2008), author of (The Birthday Party, 1958), whose works are often characterised by menace or claustrophobia. Beckett also influenced Tom Stoppard (born 1937) (Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are Dead, 1966). Stoppard's works are however also notable for their high-spirited wit and the great range of intellectual issues which he tackles in different plays. Both Pinter and Stoppard continued to have new plays produced into the 1990s. Michael Frayn (born 1933) is among other playwrights noted for their use of language and ideas. He is also a novelist. He has written a number of novels, including, The Tin Men, which won the 1966 Somerset Maugham Award), The Russian Interpreter (1967, Hawthornden Prize), and Spies, which won the Whitbread Prize for Fiction in 2002.

Other Important playwrights whose careers began later in the century are: Caryl Churchill (Top Girls, 1982) and Alan Ayckbourn (Absurd Person Singular, 1972).[32]

Radio drama

An important new element in the world of British drama, from the beginnings of radio in the 1920s, was the commissioning of plays, or the adaption of existing plays, by BBC radio. This was especially important in the 1950s and 1960s (and from the 1960s for television). Many major British playwrights in fact, either effectively began their careers with the BBC, or had works adapted for radio. Most of playwright Caryl Churchill's early experiences with professional drama production were as a radio playwright and, starting in 1962 with The Ants, there were nine productions with BBC radio drama up until 1973 when her stage work began to be recognised at the Royal Court Theatre.[33] Joe Orton's dramatic debut in 1963 was the radio play The Ruffian on the Stair, which was broadcast on 31 August 1964.[34] Tom Stoppard's "first professional production was in the fifteen-minute Just Before Midnight programme on BBC Radio, which showcased new dramatists".[34] John Mortimer made his radio debut as a dramatist in 1955, with his adaptation of his own novel Like Men Betrayed for the BBC Light Programme. But he made his debut as an original playwright with The Dock Brief, starring Michael Hordern as a hapless barrister, first broadcast in 1957 on BBC Radio's Third Programme, later televised with the same cast, and subsequently presented in a double bill with What Shall We Tell Caroline? at the Lyric Hammersmith in April 1958, before transferring to the Garrick Theatre. Mortimer is most famous for Rumpole of the Bailey a British television series which starred Leo McKern as Horace Rumpole, an aging London barrister who defends any and all clients. It has been spun off into a series of short stories, novels, and radio programmes.[35][36]

Other notable radio dramatists included Brendan Behan, and novelist Angela Carter. Novelist Susan Hill also wrote for BBC radio, from the early 1970s.[37] Irish playwright Brendan Behan, author of The Quare Fellow (1954), was commissioned by the BBC to write a radio play The Big House (1956); prior to this he had written two plays Moving Outand A Garden Party for Irish radio.[38]

Among the most famous works created for radio, are Dylan Thomas's Under Milk Wood (1954), Samuel Beckett's All That Fall (1957), Harold Pinter's A Slight Ache (1959) and Robert Bolt's A Man for All Seasons (1954).[39] Samuel Beckett wrote a number of short radio plays in the 1950s and 1960s, and later for television. Beckett's radio play Embers was first broadcast on the BBC Third Programme on 24 June 1959, and won the RAI prize at the Prix Italia awards later that year.[40]

Poetry

Major poets like T. S. Eliot, W. H. Auden and Dylan Thomas were still publishing in this period. Though W. H. Auden's (1907–1973) career began in the 1930s and 1940s he published several volumes in the 1950s and 1960s. His stature in modern literature has been contested, but probably the most common critical view from the 1930s onward ranked him as one of the three major twentieth-century British poets, and heir to Eliot and Yeats.[41] Stephen Spender (1909 – 1995)), whose career began in the 1930s, was another important poet.

New poets starting their careers in the 1950s and 1960s include Philip Larkin (1922–1985) (The Whitsun Weddings, 1964), Ted Hughes (1930–1998) (The Hawk in the Rain, 1957) and Irishman (Northern Ireland) Seamus Heaney (1939–2013) (Death of a Naturalist, 1966). Northern Ireland has also produced a number of other significant poets, including Derek Mahon and Paul Muldoon. In the 1960s and 1970s Martian poetry aimed to break the grip of 'the familiar', by describing ordinary things in unfamiliar ways, as though, for example, through the eyes of a Martian. Poets most closely associated with it are Craig Raine and Christopher Reid. Martin Amis, an important contemporary novelist, carried this defamiliarisation into fiction.

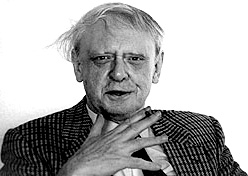

Another literary movement in this period was the British Poetry Revival, a wide-reaching collection of groupings and subgroupings which embraces performance, sound and concrete poetry. Leading poets associated with this movement include J. H. Prynne, Eric Mottram, Tom Raworth, Denise Riley and Lee Harwood.[42] The Mersey Beat poets were Adrian Henri, Brian Patten and Roger McGough. Their work was a self-conscious attempt at creating an English equivalent to the Beats. Many of their poems were written in protest against the established social order and, particularly, the threat of nuclear war. Other noteworthy later 20th-century poets are Welshman R. S. Thomas, Geoffrey Hill, Charles Tomlinson Carol Ann Duffy (Poet Laureate from 2009 to 2019) and Simon Armitage, the current laureate.[43] Geoffrey Hill (born 1932) is considered one of the most distinguished English poets of his generation,[44] Although frequently described as a "difficult" poet, Hill has retorted that supposedly difficult poetry can be "the most democratic because you are doing your audience the honour of supposing they are intelligent human beings".[45] Charles Tomlinson (1927–2015) is another important English poet of an older generation, though "since his first publication in 1951, has built a career that has seen more notice in the international scene than in his native England; this may explain, and be explained by, his international vision of poetry".[46] The critic Michael Hennessy has described Tomlinson as "the most international and least provincial English poet of his generation".[47] His poetry has won international recognition and has received many prizes in Europe and the United States.[46]

Writers of the British Commonwealth

Doris Lessing from Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, published her first novel The Grass is Singing in 1950, after immigrating to England. She initially wrote about her African experiences. Lessing soon became a dominant presence in the English literary scene, frequently publishing right through the century, and won the nobel prize for literature in 2007. Her other works include a sequence of five novels collectively called Children of Violence (1952–69), The Golden Notebook (1962), The Good Terrorist (1985), and a sequence of five science fiction novels the Canopus in Argos: Archives (1979–83). Indeed, from 1950 on a significant number of major writers came from countries that had over the centuries been settled by the British, other than America which had been producing significant writers from at least the Victorian period. There had of course been a few important works in English prior to 1950 from the then British Empire. The South African writer Olive Schreiner's famous novel The Story of an African Farm was published in 1883 and New Zealander Katherine Mansfield published her first collection of short stories, In a German Pension, in 1911. The first major English-language novelist from the Indian sub-continent, R. K. Narayan (1906–2001), began publishing in England in the 1930s, encouraged by English novelist Graham Greene.[48] Caribbean writer Jean Rhys's writing career began as early as 1928, though her most famous work, Wide Sargasso Sea, was not published until 1966. South Africa's Alan Paton's famous Cry, the Beloved Country dates from 1948.

Salman Rushdie is among a number of post Second World War writers from the former British colonies who permanently settled in Britain. Rushdie achieved fame with Midnight's Children 1981, which was awarded both the James Tait Black Memorial Prize and Booker prize, and was named Booker of Bookers in 1993. His most controversial novel The Satanic Verses 1989, was inspired in part by the life of Muhammad. V. S. Naipaul (1932–2018), born in Trinidad, was another immigrant, who wrote among other things A House for Mr Biswas (1961) and A Bend in the River (1979). Naipaul won the Nobel Prize in Literature.[49] Also from the West Indies was George Lamming (1927–2022), who wrote In the Castle of My Skin (1953), while from Pakistan, came Hanif Kureshi (born 1954), a playwright, screenwriter, filmmaker, novelist and short story writer. His book The Buddha of Suburbia (1990) won the Whitbread Award for the best first novel, and was also made into a BBC television series. Another important immigrant writer Kazuo Ishiguro (born 1954) was born in Japan, but his parents immigrated to Britain when he was six.[50] His works include The Remains of the Day 1989, Never Let Me Go 2005.

From Nigeria a number of writers have achieved an international reputation for works in English, including novelist Chinua Achebe (1930–2013), who published Things Fall Apart in 1958, as well as playwright Wole Soyinka (born 1934) and novelist Buchi Emecheta (1944–2017). Soyinka won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1986, as did South African novelist Nadine Gordimer in 1995. Other South African writers in English are novelist J. M. Coetzee (Nobel Prize 2003) and playwright Athol Fugard. Kenya's most internationally renowned author is Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o who has written novels, plays and short stories in English. Poet Derek Walcott, from St Lucia in the Caribbean, was another Nobel Prize winner in 1992. Two Irishmen and an Australian were also winners in the period after 1940: novelist and playwright, Samuel Beckett (1969); poet Seamus Heaney (1995); Patrick White (1973), a major novelist in this period, whose first work was published in 1939. Another noteworthy Australian writer at the end of this period is poet Les Murray. The contemporary Australian novelist Peter Carey (born 1943) is one of only four writers to have won the Booker Prize twice—the others being J. G. Farrell, J. M. Coetzee and Hilary Mantel.[51]

Among Canadian writers who have achieved an international reputation, are novelist and poet Margaret Atwood, poet, songwriter and novelist Leonard Cohen, short story writer Alice Munro, and more recently poet Anne Carson. Another admired Canadian novelist and poet is Michael Ondaatje, who was born in Sri Lanka.

American literature

From 1940 into the 21st century, American playwrights, poets and novelists have continued to be internationally prominent.

Post-modern literature

The term Postmodern literature is used to describe certain tendencies in post-World War II literature. It is both a continuation of the experimentation championed by writers of the modernist period (relying heavily, for example, on fragmentation, paradox, questionable narrators, etc.) and a reaction against Enlightenment ideas implicit in Modernist literature. Postmodern literature, like postmodernism as a whole, is difficult to define and there is little agreement on the exact characteristics, scope, and importance of postmodern literature. Among postmodern writers are the Americans Henry Miller, William S. Burroughs, Joseph Heller, Kurt Vonnegut, Hunter S. Thompson, Truman Capote and Thomas Pynchon.

20th-century genre literature

Agatha Christie (1890–1976) was a crime writer of novels, short stories and plays, who is best remembered for her 80 detective novels as well as her successful plays for the West End theatre. Christie's works, particularly those featuring the detectives Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple, have given her the title "Queen of Crime", and she was one of the most important and innovative writers in this genre. Christie's novels include Murder on the Orient Express, Death on the Nile and And Then There Were None. Another popular writer during the Golden Age of detective fiction was Dorothy L. Sayers (1893–1957). Other recent noteworthy writers in this genre are Ruth Rendell, P. D. James and Scot Ian Rankin.

Erskine Childers' The Riddle of the Sands (1903), is an early example of spy fiction. A noted writer in the spy novel genre was John le Carré, while in thriller writing, Ian Fleming created the character James Bond 007 in January 1952, while on holiday at his Jamaican estate, Goldeneye. Fleming chronicled Bond's adventures in twelve novels, including Casino Royale (1953), Live and Let Die (1954), Dr. No (1958), Goldfinger (1959), Thunderball (1961), and nine short story works.

Hungarian-born Emma Orczy's (1865–1947) original play, The Scarlet Pimpernel, opened in October 1903 at Nottingham's Theatre Royal but was not a success. However, with a rewritten last act, it opened at the New Theatre in London in January 1905. The premier of the London production was enthusiastically received by the audience, running 122 performances and enjoying numerous revivals. The Scarlet Pimpernel became a favourite of London audiences, playing more than 2,000 performances and becoming one of the most popular shows staged in England to that date.[citation needed] The novel The Scarlet Pimpernel was published soon after the play opened and was an immediate success. Orczy gained a following of readers in Britain and throughout the world. The popularity of the novel encouraged her to write a number of sequels for her "reckless daredevil" over the next 35 years. The play was performed to great acclaim in France, Italy, Germany and Spain, while the novel was translated into 16 languages. Subsequently, the story has been adapted for television, film, a musical and other media.

John Buchan (1875–1940) published the adventure novel The Thirty-Nine Steps in 1915.

The novelist Georgette Heyer created the historical romance genre.

The Kailyard school of Scottish writers, notably J. M. Barrie (1869–1937), creator of Peter Pan (1904), presented an idealised version of society and brought of fantasy and folklore back into fashion. In 1908, Kenneth Grahame (1859–1932) wrote the children's classic The Wind in the Willows. An informal literary discussion group associated with the English faculty at the University of Oxford, were the "Inklings". Its leading members were the major fantasy novelists; C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien. Lewis is especially known for The Chronicles of Narnia, while Tolkien is best known as the author of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. Another significant writer is Alan Garner author of Elidor (1965), while Terry Pratchett is a more recent fantasy writer. Roald Dahl rose to prominence with his children's fantasy novels, such as James and the Giant Peach and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, often inspired by experiences from his childhood, which are notable for their often unexpected endings, and J. K. Rowling author of the highly successful Harry Potter series and Philip Pullman famous for his His Dark Materials trilogy are other significant authors of fantasy novels for younger readers.

Noted writers in the field of comic books are Neil Gaiman, and Alan Moore; Gaiman also produces graphic novels.

In the later decades of the 20th century, the genre of science fiction began to be taken more seriously because of the work of writers such as Arthur C. Clarke's (2001: A Space Odyssey), Isaac Asimov, Ursula K. Le Guin, Robert Heinlein, Michael Moorcock and Kim Stanley Robinson. Another prominent writer in this genre, Douglas Adams, is particularly associated with the comic science fiction work, The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy, which began life as a radio series in 1978. Mainstream novelists such as Doris Lessing and Margaret Atwood also wrote works in this genre, while Scottish novelist Ian M. Banks has also achieved a reputation as both a writer of traditional and science fiction novels.

Winners of the Nobel Prize in Literature

See also

- African literature; and see former British colonies, Nigeria, Kenya, South African literature, etc.

- Australian literature

- Canadian literature

- Caribbean literature

- Indian English literature

- New Zealand literature

- Pakistani English literature

References

- ↑ Abrams, M. H., A Glossary of literary Terms (7th edition). (New York: Harcourt Brace), 1999), p. 167.

- ↑ Abrams, p. 167.

- ↑ Abrams, p. 168.

- ↑ Marshall Berman, All that is Solid Melts into Air. (Harmsworth: Penguin,1988), p. 23.

- ↑ Drabble 1996, p. 632.

- ↑ Literature 1923, The Nobel prize, http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1923/, retrieved 3 June 2007.

- ↑ Frenz, Horst, ed. (1969), "Yeats bio", The Nobel Prize in Literature 1923, Nobel Lectures, Literature 1901–1967, http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/1923/yeats-bio.html, retrieved 23 May 2007.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 The Oxford Companion to English Literature, ed. Margaret Drabble, p. 791.

- ↑ Drabble 1996, p. 377, 988.

- ↑ The Oxford Companion to English Literature. (1996), p. 781.

- ↑ "English literature". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 15 November 2012.

- ↑ The Oxford Companion to English Literature, ed. Margaret Drabble, p. 562.

- ↑ Beebe, Maurice (Fall 1972). "Ulysses and the Age of Modernism". James Joyce Quarterly (University of Tulsa) 10 (1): p. 176.

- ↑ The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature, ed. Marion Wynne Davies (New York: Prentice Hall, 1990), p. 118.

- ↑ Adam Charles Roberts (2000), "The History of Science Fiction": p. 48 in Science Fiction, Routledge, ISBN:0-415-19204-8.

- ↑ Book Review: A Voyage to Arcturus (1920) by David Lindsay – Review by Paul M. Kieniewicz, 2003.

- ↑ Lindskoog, Kathryn, A Voyage to Arcturus, C. S. Lewis, and The Dark Tower

- ↑ "Rudyard Kipling". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. Encyclopædia Britannica Inc., 2012. Web. 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Ahlquist 2012, p. 212.

- ↑ Roe, Sue, and Susan Sellers, The Cambridge Companion to Virginia Woolf (Cambridge University Press, 2000), p. 219.

- ↑ Drabble 1996, p. 660.

- ↑ Davies 1990, p. 644.

- ↑ Dettmar, Kevin JH (2006), "Modernism", in Kastan, David Scott, The Oxford Encyclopedia of British Literature, Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordreference.com/.

- ↑ Birch, Dinah, ed. (27 October 2011), "modernism", The Oxford Companion to English Literature, Oxford Reference Online, Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordreference.com.

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to Irish Literature, ed. John Wilson Foster. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- ↑ Bradbury, Malcolm (1969), Introduction to Scenes from Provincial Life, London: Macmillan.

- ↑ Dugdale, John (4 April 2014). "Julian Barnes's pseudonymous detective novels stay under cover". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/booksblog/2014/apr/04/julian-barnes-detective-novels-duffy-dan-kavanagh.

- ↑ "John Banville". Dictionary of Irish Literature, ed. Robert Hogan (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996).

- ↑ Brown, Mark (23 January 2008). "Perfect Day for AL Kennedy as she takes Costa book prize". The Guardian (London). http://books.guardian.co.uk/costa2007/story/0,,2245282,00.html.

- ↑ "Literatur-Staatspreis an Britin verliehen" (in de). ORF Salzburg (Austrian Broadcasting Company). 27 July 2008. http://salzburg.orf.at/stories/295874/.

- ↑ Galloway, Janice (12 October 2002), "Rereading Lanark by Alasdair Gray". The Guardian.

- ↑ Childs, Peter; Storry, Mike (1999). Encyclopedia of Contemporary British Culture. London: Routledge. pp. 399–400. ISBN 978-0415147262.

- ↑ "Churchill, Caryl", Playwrights, Doollee, http://www.doollee.com/PlaywrightsC/churchill-caryl.html.

- ↑ Jump up to: 34.0 34.1 Crook, Tim, International radio drama, UK: IRDP, http://www.irdp.co.uk/radiodrama.htm.

- ↑ John Mortimer Radio Plays, UK: Sutton elms, http://www.suttonelms.org.uk/jmortimer.html.

- ↑ John Mortimer Biography (1923–2009), Film reference, http://www.filmreference.com/film/69/John-Mortimer.html.

- ↑ Sutton elms, UK, http://www.suttonelms.org.uk/.

- ↑ Cody, Gabrielle H, ed., "Brendan Behan", The Columbia encyclopedia of modern drama, Archives, IE: RTÉ, http://www.rte.ie/archives/exhibitions/925-brendan-behan/.

- ↑ Trewin, J. C., "Critic on the Hearth." Listener [London, England] 5 August 1954: 224.

- ↑ "Winners 1949–2007", Prix Italia, Past editions, RAI, 2008, http://www.prixitalia.rai.it/2008/pdf/vincitori_edizionipassate_en.pdf.

- ↑ Smith, Stan (2004). "Introduction". In Stan Smith. The Cambridge Companion to W. H. Auden. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–14. ISBN:0-521-82962-3.

- ↑ Greene 2012, p. 426.

- ↑ "Simon Armitage: 'Witty and profound' writer to be next Poet Laureate". BBC News. 10 May 2019. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/entertainment-arts-48228837.

- ↑ Bloom, Harold, ed. (1986), Geoffrey Hill, Modern Critical Views, Infobase.

- ↑ Flood, Alison (31 January 2012). "Carol Ann Duffy is 'wrong' about poetry, says Geoffrey Hill". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2012/jan/31/carol-ann-duffy-oxford-professory-poetry.

- ↑ Jump up to: 46.0 46.1 Charles Tomlinson, UK: Carcanet Press, http://www.carcanet.co.uk/cgi-bin/indexer?owner_id=770.

- ↑ Charles Tomlinson, Poetry foundation, 21 August 2022, http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/charles-tomlinson.

- ↑ Drabble 1996, p. 697.

- ↑ "2001 Laureates". Literature. The Nobel prize. http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/literature/laureates/2001/.

- ↑ Drabble 1996, p. 506.

- ↑ Man Booker official site: J. G. Farrell [1]; Hilary Mantel "Dame Hilary Mantel | the Man Booker Prizes". http://themanbookerprize.com/people/hilary-mantel.; J. M. Coetzee: "J M Coetzee | the Man Booker Prizes". http://themanbookerprize.com/people/j-m-coetzee..

Bibliography

- Ahlquist, Dale (2012), The Complete Thinker: The Marvelous Mind of G.K. Chesterton, Ignatius Press, ISBN 978-1-58617-675-4.

- Davies, Marion Wynne, ed. (1990), The Bloomsbury Guide to English Literature, New York: Prentice Hall.

- Drabble, Margaret, ed. (1996), The Oxford Companion to English Literature, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fulk, RD; Cain, Christopher M (2003), A History of Old English Literature, Malden: Blackwell.

- Greene, Roland, ed (2012). "The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics". The Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics (4th rev. ed.). Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. pp. 420–428. ISBN 978-0-691-15491-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=uKiC6IeFR2UC.

- Kiernan, Kevin (1996), Beowulf and the Beowulf Manuscript, Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, ISBN 0-472-08412-7, https://books.google.com/books?id=Yv8cnwEACAAJ.

- Orchard, Andy (2003), A Critical Companion to Beowulf, Cambridge: DS Brewer.

- Robinson, Fred C. (2001), The Cambridge Companion to Beowulf, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 143.

- Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1958), Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, London: Oxford University Press.

- Ward, AW; Waller, AR; Trent, WP et al., eds. (1907–21), History of English and American literature, New York: GP Putnam's Sons University Press.

External links

| Library resources about English literature |

- Discovering Literature: 20th century at the British Library

- The English Literary Canon

- British literature – Books tagged British literature LibraryThing

- A Bibliography of Literary Theory, Criticism and Philology Ed. José Ángel García Landa, (University of Zaragoza, Spain)

|