Physics:Angle of attack

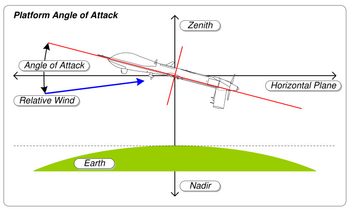

In fluid dynamics, angle of attack (AOA, α, or ) is the angle between a reference line on a body (often the chord line of an airfoil) and the vector representing the relative motion between the body and the fluid through which it is moving.[1] Angle of attack is the angle between the body's reference line and the oncoming flow. This article focuses on the most common application, the angle of attack of a wing or airfoil moving through air.

In aerodynamics, angle of attack specifies the angle between the chord line of the wing of a fixed-wing aircraft and the vector representing the relative motion between the aircraft and the atmosphere. Since a wing can have twist, a chord line of the whole wing may not be definable, so an alternate reference line is simply defined. Often, the chord line of the root of the wing is chosen as the reference line. Another choice is to use a horizontal line on the fuselage as the reference line (and also as the longitudinal axis).[2] Some authors[3][4] do not use an arbitrary chord line but use the zero lift axis where, by definition, zero angle of attack corresponds to zero coefficient of lift.

Some British authors have used the term angle of incidence instead of angle of attack.[5] However, this can lead to confusion with the term riggers' angle of incidence meaning the angle between the chord of an airfoil and some fixed datum in the airplane.[6]

Relation between angle of attack and lift coefficient

The lift coefficient of a fixed-wing aircraft varies with angle of attack. Increasing angle of attack is associated with increasing lift coefficient up to the maximum lift coefficient, after which lift coefficient decreases.[7]

As the angle of attack of a fixed-wing aircraft increases, separation of the airflow from the upper surface of the wing becomes more pronounced, leading to a reduction in the rate of increase of the lift coefficient. The figure shows a typical curve for a cambered straight wing. Cambered airfoils are curved such that they generate some lift at small negative angles of attack. A symmetrical wing has zero lift at 0 degrees angle of attack. The lift curve is also influenced by the wing shape, including its airfoil section and wing planform. A swept wing has a lower, flatter curve with a higher critical angle.

Critical angle of attack

The critical angle of attack is the angle of attack which produces the maximum lift coefficient. This is also called the "stall angle of attack". Below the critical angle of attack, as the angle of attack decreases, the lift coefficient decreases. Conversely, above the critical angle of attack, as the angle of attack increases, the air begins to flow less smoothly over the upper surface of the airfoil and begins to separate from the upper surface. On most airfoil shapes, as the angle of attack increases, the upper surface separation point of the flow moves from the trailing edge towards the leading edge. At the critical angle of attack, upper surface flow is more separated and the airfoil or wing is producing its maximum lift coefficient. As the angle of attack increases further, the upper surface flow becomes more fully separated and the lift coefficient reduces further.[7]

Above this critical angle of attack, the aircraft is said to be in a stall. A fixed-wing aircraft by definition is stalled at or above the critical angle of attack rather than at or below a particular airspeed. The airspeed at which the aircraft stalls varies with the weight of the aircraft, the load factor, the center of gravity of the aircraft and other factors. However, the aircraft always stalls at the same critical angle of attack. The critical or stalling angle of attack is typically around 15° - 18° for many airfoils.

Some aircraft are equipped with a built-in flight computer that automatically prevents the aircraft from increasing the angle of attack any further when a maximum angle of attack is reached, regardless of pilot input. This is called the 'angle of attack limiter' or 'alpha limiter'. Modern airliners that have fly-by-wire technology avoid the critical angle of attack by means of software in the computer systems that govern the flight control surfaces.[8]

In takeoff and landing operations from short runways (STOL), such as Naval Aircraft Carrier operations and STOL backcountry flying, aircraft may be equipped with the angle of attack or Lift Reserve Indicators. These indicators measure the angle of attack (AOA) or the Potential of Wing Lift (POWL, or Lift Reserve) directly and help the pilot fly close to the stalling point with greater precision. STOL operations require the aircraft to be able to operate close to the critical angle of attack during landings and at the best angle of climb during takeoffs. Angle of attack indicators are used by pilots for maximum performance during these maneuvers, since airspeed information is only indirectly related to stall behavior.

Very high alpha

Some military aircraft are able to achieve controlled flight at very high angles of attack, but at the cost of massive induced drag. This provides the aircraft with great agility. A famous example is Pugachev's Cobra. Although the aircraft experiences high angles of attack throughout the maneuver, the aircraft is not capable of either aerodynamic directional control or maintaining level flight until the maneuver ends. The Cobra is an example of supermaneuvering[9][10] as the aircraft's wings are well beyond the critical angle of attack for most of the maneuver.

Additional aerodynamic surfaces known as "high-lift devices" including leading edge wing root extensions allow fighter aircraft much greater flyable 'true' alpha, up to over 45°, compared to about 20° for aircraft without these devices. This can be helpful at high altitudes where even slight maneuvering may require high angles of attack due to the low density of air in the upper atmosphere as well as at low speed at low altitude where the margin between level flight AoA and stall AoA is reduced. The high AoA capability of the aircraft provides a buffer for the pilot that makes stalling the airplane (which occurs when critical AoA is exceeded) more difficult. However, military aircraft usually do not obtain such high alpha in combat, as it robs the aircraft of speed very quickly due to induced drag, and, in extreme cases, increased frontal area and parasitic drag. Not only do such maneuvers slow the aircraft down, but they cause significant structural stress at high speed. Modern flight control systems tend to limit a fighter's angle of attack to well below its maximum aerodynamic limit.[citation needed]

Sailing

In sailing, the physical principles involved are the same as for aircraft—a sail is an airfoil.[11] A sail's angle of attack is the angle between the sail's chord line and the direction of the relative wind.

See also

- Air data boom, measures angle of attack

- Advance ratio

- Aircraft principal axes

- Angle of sideslip

- Bernoulli's principle

- Drag equation

- Küssner effect

- Lift (force)

References

- ↑ "Inclination Effects on Lift". 2018-04-05. https://www1.grc.nasa.gov/beginners-guide-to-aeronautics/foilinc.

- ↑ Gracey, William (1958). "Summary of Methods of Measuring Angle of Attack on Aircraft". NACA Technical Note (NASA Technical Reports) (NACA-TN-4351): 1–30. http://naca.central.cranfield.ac.uk/reports/1958/naca-tn-4351.pdf. Retrieved 2013-09-11.

- ↑ John S. Denker, See How It Flies. http://www.av8n.com/how/htm/aoa.html#sec-def-aoa

- ↑ Wolfgang Langewiesche, Stick and Rudder: An Explanation of the Art of Flying, McGraw-Hill Professional, first edition (September 1, 1990), ISBN:0-07-036240-8

- ↑ Wolfgang Langewiesche, Stick and Rudder: An Explanation of the Art of Flying, p. 7

- ↑ Kermode, A.C. (1972), Mechanics of Flight, Chapter 3 (8th edition), Pitman Publishing Limited, London ISBN:0-273-31623-0

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "NASA Lift Coefficient". http://www.grc.nasa.gov/WWW/k-12/airplane/liftco.html.

- ↑ "Fly-by-Wire Systems Enable Safer, More Efficient Flight | NASA Spinoff". https://spinoff.nasa.gov/Spinoff2011/t_5.html.

- ↑ Timothy Cowan

- ↑ DTIC

- ↑ Evans, Robin C.. "HOW A SAIL BOAT SAILS INTO THE WIND". Reports on How Things Work. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. http://web.mit.edu/2.972/www/reports/sail_boat/sail_boat.html.

- Lawford, J.A. and Nippress, K.R.; Calibration of Air-data Systems and Flow Direction Sensors (NATO) Advisory Group for Aerospace Research and Development, AGARDograph No. 300 Vol. 1 (AGARD AG-300 Vol. 1); "Calibration of Air-data Systems and Flow Direction Sensors"; Aeroplane and Armament Experimental Establishment, Boscombe Down, Salisbury, Wilts SP4 OJF, United Kingdom

- USAF & NATO Report RTO-TR-015 AC/323/(HFM-015)/TP-1 (2001).