Physics:Non-neutral plasmas

A non-neutral plasma is a plasma whose net charge creates an electric field large enough to play an important or even dominant role in the plasma dynamics.[1] The simplest non-neutral plasmas are plasmas consisting of a single charge species. Examples of single species non-neutral plasmas that have been created in laboratory experiments are plasmas consisting entirely of electrons,[2] pure ion plasmas,[3] positron plasmas,[4] and antiproton plasmas.[5]

Non-neutral plasmas are used for research into basic plasma phenomena such as cross-magnetic field transport,[6] nonlinear vortex interactions,[7] and plasma waves and instabilities.[8] They have also been used to create cold neutral antimatter, by carefully mixing and recombining cryogenic pure positron and pure antiproton plasmas. Positron plasmas are also used in atomic physics experiments that study the interaction of antimatter with neutral atoms and molecules. Cryogenic pure ion plasmas have been used in studies of strongly coupled plasmas[9] and quantum entanglement. More prosaically, pure electron plasmas are used to produce the microwaves in microwave ovens, via the magnetron instability.

Neutral plasmas in contact with a solid surface (that is, most laboratory plasmas) are typically non-neutral in their edge regions. Due to unequal loss rates to the surface for electrons and ions, an electric field (the "ambipolar field" ) builds up, acting to hold back the more mobile species until the loss rates are the same. The electrostatic potential (as measured in electron-volts) required to produce this electric field depends on many variables but is often on the order of the electron temperature.

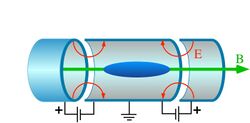

Non-neutral plasmas for which all species have the same sign of charge have exceptional confinement properties compared to neutral plasmas. They can be confined in a thermal equilibrium state using only static electric and magnetic fields, in a Penning trap configuration (see Fig. 1).[10] Confinement times of up to several hours have been achieved.[11] Using the "rotating wall" method,[12] the plasma confinement time can be increased arbitrarily.

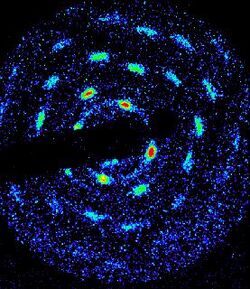

Such non-neutral plasmas can also access novel states of matter. For instance, they can be cooled to cryogenic temperatures without recombination (since there is no oppositely charged species with which to recombine). If the temperature is sufficiently low (typically on the order of 10 mK), the plasma can become a non-neutral liquid or a crystal.[13] The body-centered-cubic structure of these plasma crystals has been observed by Bragg scattering in experiments on laser-cooled pure beryllium plasmas.[9]

Equilibrium of a single species non-neutral plasma

Non-neutral plasmas with a single sign of charge can be confined for long periods of time using only static electric and magnetic fields. One such configuration is called a Penning trap, after the inventor F. M. Penning. The cylindrical version of the trap is also sometimes referred to as a Penning-Malmberg trap, after Prof. John Malmberg. The trap consists of several cylindrically symmetric electrodes and a uniform magnetic field applied along the axis of the trap (Fig 1). Plasmas are confined in the axial direction by biasing the end electrodes so as to create an axial potential well that will trap charges of a given sign (the sign is assumed to be positive in the figure). In the radial direction, confinement is provided by the v × B Lorentz force due to rotation of the plasma about the trap axis. Plasma rotation causes an inward directed Lorentz force that just balances the outward directed forces caused by the unneutralized plasma as well as the centrifugal force. Mathematically, radial force balance implies a balance between electric, magnetic and centrifugal forces:[1]

-

()

where particles are assumed to have mass m and charge q, r is radial distance from the trap axis and Er is the radial component of the electric field. This quadratic equation can be solved for the rotational velocity , leading to two solutions, a slow-rotation and a fast-rotation solution. The rate of rotation for these two solutions can be written as

- ,

where is the cyclotron frequency. Depending on the radial electric field, the solutions for the rotation rate fall in the range . The slow and fast rotation modes meet when the electric field is such that . This is called the Brillouin limit; it is an equation for the maximum possible radial electric field that allows plasma confinement.

This radial electric field can be related to the plasma density n through the Poisson equation,

and this equation can be used to obtain a relation between the density and the plasma rotation rate. If we assume that the rotation rate is uniform in radius (i.e. the plasma rotates as a rigid body), then Eq. (1) implies that the radial electric field is proportional to radius r. Solving for Er from this equation in terms of and substituting the result into Poisson's equation yields

-

()

This equation implies that the maximum possible density occurs at the Brillouin limit, and has the value

where is the speed of light. Thus, the rest energy density of the plasma, n·m·c2, is less than or equal to the magnetic energy density of the magnetic field. This is a fairly stringent requirement on the density. For a magnetic field of 10 tesla, the Brillouin density for electrons is only nB = 4.8×1014 cm−3.

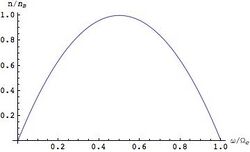

The density predicted by Eq.(2), scaled by the Brillouin density, is shown as a function of rotation rate in Fig. (2). Two rotation rates yield the same density, corresponding to the slow and fast rotation solutions.

Plasma loss processes; the rotating wall method

In experiments on single species plasmas, plasma rotation rates in the tens of kHz range are not uncommon, even in the slow rotation mode. This rapid rotation is necessary to provide the confining radial Lorentz force for the plasma. However, if there is neutral gas in the trap, collisions between the plasma and the gas cause the plasma rotation to slow, leading to radial expansion of the plasma until it comes in contact with the surrounding electrodes and is lost. This loss process can be alleviated by operating the trap in an ultra high vacuum. However, even under such conditions the plasma rotation can still be slowed through the interaction of the plasma with "errors" in the external confinement fields. If these fields are not perfectly cylindrically symmetric, the asymmetries can torque on the plasma, reducing the rotation rate. Such field errors are unavoidable in any actual experiment, and limit the plasma confinement time.[14]

It is possible to overcome this plasma loss mechanism by applying a rotating field error to the plasma. If the error rotates faster than the plasma, it acts to spin up the plasma (similar to how the spinning blade of a blender causes the food to spin), counteracting the effect of field errors that are stationary in the frame of the laboratory. This rotating field error is referred to as a "rotating wall", after the theory idea that one could reverse the effect of a trap asymmetry by simply rotating the entire trap at the plasma rotation frequency. Since this is impractical, one instead rotates the trap electric field rather than the entire trap, by applying suitably phased voltages to a set of electrodes surrounding the plasma.[12] [15]

Cryogenic non-neutral plasmas: correlated states

When a non-neutral plasma is cooled to cryogenic temperatures, it does not recombine to a neutral gas as would a neutral plasma, because there are no oppositely charged particles with which to recombine. As a result, the system can access novel strongly coupled non-neutral states of matter, including plasma crystals consisting solely of a single charge species. These strongly coupled non-neutral plasmas are parametrized by the coupling parameter Γ, defined as

where is the temperature and is the Wigner–Seitz radius (or mean inter-particle spacing), given in terms of the density by the expression . The coupling parameter can be thought of as the ratio of the mean interaction energy between nearest-neighbor pairs, , and the mean kinetic energy of order . When this ratio is small, interactions are weak and the plasma is nearly an ideal gas of charges moving in the mean-field produced by the other charges. However, when interactions between particles are important and the plasma behaves more like a liquid, or even a crystal if is sufficiently large. In fact, computer simulations and theory have predicted that for an infinite homogeneous plasma the system exhibits a gradual onset of short-range order consistent with a liquid-like state for , and there is predicted to be a first-order phase transition to a body-centered-cubic crystal for .[10]

Experiments have observed this crystalline state in a pure beryllium ion plasma that was laser-cooled to the millikelvin temperature range. The mean inter-particle spacing in this pure ion crystal was on the order of 10-20 µm, much larger than in neutral crystalline matter. This spacing corresponds to a density on the order of 108-109 cm−3, somewhat less than the Brillouin limit for beryllium in the 4.5 tesla magnetic field of the experiment. Cryogenic temperatures were then required in order to obtain a value in the strongly coupled regime. The experiments measured the crystal structure by the Bragg-scattering technique, wherein a collimated laser beam was scattered off of the crystal, displaying Bragg peaks at the expected scattering angles for a bcc lattice (See Fig. 3).[9]

When small numbers of ions are laser-cooled, they form crystalline "Coulomb clusters". The symmetry of the cluster depends on the form of the external confinement fields. An interactive 3D view of some of the clusters can be found here.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 R. C. Davidson, "Physics of Non-neutral Plasmas", (Addison-Wesley, Redwood City, CA, 1990)

- ↑ Malmberg, J. H.; deGrassie, J. S. (1975-09-01). "Properties of Nonneutral Plasma". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 35 (9): 577–580. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.35.577. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ Bollinger, J. J.; Wineland, D. J. (1984-07-23). "Strongly Coupled Nonneutral Ion Plasma". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 53 (4): 348–351. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.53.348. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ Danielson, J. R.; Dubin, D. H. E.; Greaves, R. G.; Surko, C. M. (2015-03-17). "Plasma and trap-based techniques for science with positrons". Reviews of Modern Physics (American Physical Society (APS)) 87 (1): 247–306. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.87.247. ISSN 0034-6861.

- ↑ Andresen, G. B.; Ashkezari, M. D.; Baquero-Ruiz, M.; Bertsche, W.; Bowe, P. D.; Butler, E.; Cesar, C. L.; Chapman, S. et al. (2010-07-02). "Evaporative Cooling of Antiprotons to Cryogenic Temperatures". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 105 (1): 013003. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.105.013003. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ F. Anderegg, "Internal Transport in Non-Neutral Plasmas," presented at Winter School on Physics with Trapped Charged Particles; to appear, Imperial College Press (2013) http://nnp.ucsd.edu/pdf_files/Anderegg_transport_leshouches_2012.pdf

- ↑ Durkin, D.; Fajans, J. (2000). "Experiments on two-dimensional vortex patterns". Physics of Fluids (AIP Publishing) 12 (2): 289–293. doi:10.1063/1.870307. ISSN 1070-6631.

- ↑ Anderegg, F.; Driscoll, C. F.; Dubin, D. H. E.; O’Neil, T. M. (2009-03-02). "Wave-Particle Interactions in Electron Acoustic Waves in Pure Ion Plasmas". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 102 (9): 095001. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.102.095001. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Tan, Joseph N.; Bollinger, J. J.; Jelenkovic, B.; Wineland, D. J. (1995-12-04). "Long-Range Order in Laser-Cooled, Atomic-Ion Wigner Crystals Observed by Bragg Scattering". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 75 (23): 4198–4201. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.75.4198. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Dubin, Daniel H. E.; O’Neil, T. M. (1999-01-01). "Trapped nonneutral plasmas, liquids, and crystals (the thermal equilibrium states)". Reviews of Modern Physics (American Physical Society (APS)) 71 (1): 87–172. doi:10.1103/revmodphys.71.87. ISSN 0034-6861.

- ↑ J. H. Malmberg et al., "The Cryogenic Pure Electron Plasma", Proceedings of the 1984 Sendai Symposium on Plasma Nonlinear Phenomena" http://nnp.ucsd.edu/pdf_files/Proc_84_Sendai_1X.pdf

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Huang, X.-P.; Anderegg, F.; Hollmann, E. M.; Driscoll, C. F.; O'Neil, T. M. (1997-02-03). "Steady-State Confinement of Non-neutral Plasmas by Rotating Electric Fields". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 78 (5): 875–878. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.78.875. ISSN 0031-9007. https://semanticscholar.org/paper/6a00a573bcb53ab66692d12ac222ce2b02b727d1.

- ↑ Malmberg, J. H.; O'Neil, T. M. (1977-11-21). "Pure Electron Plasma, Liquid, and Crystal". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 39 (21): 1333–1336. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.39.1333. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ Malmberg, J. H.; Driscoll, C. F. (1980-03-10). "Long-Time Containment of a Pure Electron Plasma". Physical Review Letters (American Physical Society (APS)) 44 (10): 654–657. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.44.654. ISSN 0031-9007.

- ↑ Danielson, J. R.; Surko, C. M. (2006). "Radial compression and torque-balanced steady states of single-component plasmas in Penning-Malmberg traps". Physics of Plasmas (AIP Publishing) 13 (5): 055706. doi:10.1063/1.2179410. ISSN 1070-664X.