Place:Antananarivo

Antananarivo Tananarive | |

|---|---|

Capital city | |

Lake Anosy Central Antananarivo, Jacarandas blooming, Lake Anozy, Royal chapel, Chemin des Dames, bust of Philibert Tsiranana, Mausolée d'Andrainarivo, Train station, Presidential office | |

| Nickname(s): Tana | |

| Coordinates: [ ⚑ ] : 18°54′36″S 47°31′30″E / 18.91°S 47.525°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Analamanga |

| Historic Countries/Colonies | Merina Kingdom Malagasy Protectorate French Madagascar |

| Founded | 1610 or 1625 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor of Antananarivo | Naina Andriantsitohaina |

| Area | |

| • Capital city | 85 km2 (33 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,276 m (4,186 ft) |

| Population (2018 Census) | |

| • Capital city | 1,274,225 |

| • Density | 15,000/km2 (39,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,300,000 |

| [1] | |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (East Africa Time) |

| Area code(s) | (+261) 023 |

| Climate | Cwa |

| Major Airport(s) | Ivato International Airport |

| Website | www.mairie-antananarivo.mg (in French) |

Antananarivo (French: Tananarive, pronounced [tananaʁiv]), also known by its colonial shorthand form Tana (pronounced [tana]), is the capital and largest city of Madagascar . The administrative area of the city, known as Antananarivo-Renivohitra ("Antananarivo-Mother Hill" or "Antananarivo-Capital"), is the capital of Analamanga region. The city sits at 1,280 m (4,199 ft) above sea level in the center of the island, the highest national capital by elevation among the island countries. It has been the country's largest population center since at least the 18th century. The presidency, National Assembly, Senate and Supreme Court are located there, as are 21 diplomatic missions and the headquarters of many national and international businesses and NGOs. It has more universities, nightclubs, art venues, and medical services than any city on the island. Several national and local sports teams, including the championship-winning national rugby team, the Makis, are based here.

Antananarivo was historically the capital of the Merina people, who continue to form the majority of the city's 1,274,225 (2018 Census[2][3]) inhabitants. The surrounding urban areas have a total metropolitan population approaching three million. All eighteen Malagasy ethnic groups, as well as residents of Chinese, Indian, European and other origins, are represented in the city. It was founded circa 1610, when the Merina King Andrianjaka (1612–1630) expelled the Vazimba inhabitants of the village of Analamanga. Declaring it the site of his capital, Andrianjaka built a rova (fortified royal dwelling) that expanded to become the royal palaces of the Kingdom of Imerina. The city retained the name Analamanga until the reign of King Andriamasinavalona (1675–1710), who renamed it Antananarivo ("City of the Thousand") in honor of Andrianjaka's soldiers.

The city served as the capital of the Kingdom of Imerina until 1710 when Imerina split into four warring quadrants. Antananarivo became the capital of the southern quadrant until 1794, when King Andrianampoinimerina of Ambohimanga captured the province and restored it as the capital of a united Kingdom of Imerina, also bringing neighboring ethnic groups under Merina control. These conquests continued under his son, Radama I, who eventually controlled over two-thirds of the island, leading him to be considered the King of Madagascar by European diplomats. Antananarivo remained the island's capital after Madagascar was colonized by the French in 1897, and after independence in 1960.

The city is now managed by the Commune Urbaine d'Antananarivo (CUA) under the direction of its President of the Special Delegation, Ny Havana Andriamanjato, appointed in March 2014. Limited funds and mismanagement have hampered consecutive CUA efforts to manage overcrowding and traffic, waste management, pollution, security, public water and electricity, and other challenges linked to explosive population growth. Major historic landmarks and attractions in the city include the reconstructed royal palaces and the Andafiavaratra Palace, the tomb of Rainiharo, Tsimbazaza Zoo, Mahamasina Stadium, Lake Anosy, four 19th-century martyr churches, and the Museum of Art and Archaeology.

Pronunciation and etymology

The English pronunciation of Antananarivo is /ˌæntəˌnænəˈriːvoʊ/ or /ˌɑːntəˌnɑːnəˈriːvoʊ/.[4] The Malagasy pronunciation is [antananaˈrivʷ], and the pronunciation of the old French name Tananarive is /təˌnænəˈriːv/[5] or /ˌtænənəˈriːv/[6] in English and [tananaʁiv] in French.

Antananarivo was originally the site of a town called Analamanga, meaning "Blue Forest" in the Central Highlands dialect of the Malagasy language.[7] Analamanga was established by a community of Vazimba, the island's first occupants. Merina King Andrianjaka, who migrated to the region from the southeast coast, seized the location as the site of his capital city. According to oral history, he deployed a garrison of 1,000 soldiers to successfully capture and guard the site.[7] The hill and its city retained the name Analamanga until the reign of King Andriamasinavalona, who renamed it Antananarivo ("City of the Thousand") in honor of Andrianjaka's soldiers.[8]

History

Kingdom of Imerina

Antananarivo was already a major city before the colonial era. After expelling the Vazimba who inhabited the town at the peak of Analamanga hill, Andrianjaka chose the site for his rova (fortified royal compound), which expanded over time to enclose the royal palaces and the tombs of Merina royalty.[9] The city was established in around 1610[10] or 1625[11] according to varying accounts. Early Merina kings used fanampoana (statute labor) to construct a massive system of irrigated paddy fields and dikes around the city to provide adequate rice for the growing population. These paddy fields, of which the largest is called the Betsimitatatra, continue to produce rice.[12]

Successive Merina sovereigns ruled over the Kingdom of Imerina from Analamanga through King Andriamasinavalona's reign. This sovereign gave the growing city its current name; he established the Andohalo town square outside the town gate, where all successive sovereigns delivered their royal speeches and announcements to the public, and assigned the names of numerous locations within the city based on the names of similar sites in the nearby village of Antananarivokely.[8] Andriamasinavalona designated specific territories for the hova (commoners) and each andriana (noble) subcaste, both within the neighborhoods of Antananarivo and in the countryside surrounding the capital. These territorial divisions were strictly enforced; members of subcastes were required to live within their designated territories and were not authorized to stay for extended periods in the territories reserved for others.[13] Numerous fady (taboos), including injunctions against the construction of wooden houses by non-nobles[14] and the presence of swine within the city limits, were imposed.[15]

Upon Andriamasinavalona's death in 1710, Imerina split into four warring quadrants, and Antananarivo was made the capital of the southern district.[16] During the 77-year civil war that followed, the eastern district's capital at Ambohimanga rose in prominence.[17] The last king of Ambohimanga, Andrianampoinimerina, successfully conquered Antananarivo in 1793;[18] he reunited the provinces of Imerina, ending the civil war. He moved the kingdom's political capital back to Antananarivo in 1794,[16] and declared Ambohimanga the kingdom's spiritual capital, a role it still maintains.[19] Andrianampoinimerina created a large marketplace in Analakely, establishing the city's economic center.[20]

Kingdom of Madagascar

By the time Andrianampoinimerina's son Radama I had ascended the throne upon his father's death in 1810, Antananarivo was the largest and most economically important city on the island, with a population of over 80,000 inhabitants.[21] Radama opened the city to the first European settlers, artisan missionaries of the London Missionary Society (LMS) who arrived in 1820 and opened the city's first public schools.[22] James Cameron introduced brickmaking to the island and created Lake Anosy to generate hydraulic power for industrial manufacturing.[23] Radama established a military training ground on a flat plain called Mahamasina at the base of Analamanga near the lake. Radama's subjugation of other Malagasy ethnic groups brought nearly two-thirds of the island under his control. The British diplomats who concluded trade treaties with Radama recognized him as the "ruler of Madagascar", a position he and his successors claimed despite never managing to impose their authority over the larger portion of the island's south. Thereafter, Merina sovereigns declared Antananarivo the capital of the entire island.[24]

Radama's successor Ranavalona I invited a shipwrecked craftsman named Jean Laborde to construct the tomb of Prime Minister Rainiharo, and Manjakamiadana (built 1839–1841), the largest palace at the Rova. Laborde also produced a wide range of industrial products at factories in the highland village Mantasoa and a foundry in the Antananarivo neighborhood of Isoraka.[26] Ranavalona oversaw improvements to the city's infrastructure, including the construction of the city's two largest staircases at Antaninarenina and Ambondrona, which connect la ville moyenne ("the middle town") to the central marketplace at Analakely.[25] In 1867, following a series of fires in the capital, Queen Ranavalona II issued a royal decree that permitted the use of stone and brick construction in buildings other than tombs.[23] LMS missionaries' first brick house was built in 1869; it bore a blend of English, Creole, and Malagasy design and served as a model for a new style of house that rapidly spread throughout the capital and across the highlands. Termed the trano gasy ("Malagasy house"), it is typically a two-story, brick building with four columns on the front that support a wooden veranda. In the latter third of the 19th century, these houses quickly replaced most of the traditional wooden houses of the city's aristocratic class.[27] The growing number of Christians in Imerina prompted the construction of stone churches throughout the highlands, as well as four memorial churches on key sites of martyrdom among early Malagasy Christians under the reign of Ranavalona I.[28]

Until the mid-19th century, the city remained largely concentrated around the Rova of Antananarivo on the highest peak, an area today referred to as la haute ville or la haute ("upper town"). As the population grew, the city expanded to the west; by the late 19th century it extended to the northern hilltop neighborhood of Andohalo, an area of low prestige until British missionaries made it their preferred residential district and built one of the city's memorial churches here from 1863 to 1872.[7] From 1864 to 1894, Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony governed Madagascar alongside three successive queens, Rasoherina, Ranavalona II and Ranavalona III, effecting policies that further transformed the city. In 1881, he reinstated mandatory universal education first introduced in 1820 under Radama I, requiring the construction of numerous schools and colleges, including teacher training colleges staffed by missionaries and the nation's first pharmacy, medical college, and modern hospital.[29] Rainilaiarivony built the Andafiavaratra Palace in 1873 as his residence and office at a site near the royal palace.[30]

French Madagascar

The French military invaded Antananarivo in September 1894, prompting the queen's surrender after a cannon shell blasted a hole through a building at the Rova, causing major casualties. The damage was never repaired. Andohalo square was remodeled to feature a gazebo, walkways, and planted landscaping. Claiming the island as a colony, the French administration retained Antananarivo as its capital and transcribed its name as Tananarive.[31] They chose Antaninarenina as the site for the French Governor General's Residency; upon independence, it was renamed Ambohitsorohitra Palace and converted into presidential offices. Under the French, tunnels were constructed through two of the city's largest hills, connecting disparate districts and facilitating the town's expansion. Streets were laid with cobblestones and later paved; sewer systems and electricity infrastructure was introduced. Water, previously obtained from springs at the foot of the hill, was brought from the Ikopa River.[32]

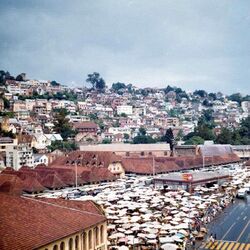

This period saw a major expansion of la ville moyenne, which spread along the lower hilltops and slopes of the city centered around the French residency. Modern urban planning was applied in la ville basse ("lower town"), which expanded from the base of the city's central hills into the surrounding rice fields. Major boulevards like Avenue de l'Indépendance, planned commercial areas like the arcades lining either side of the avenue, large parks, city squares, and other landmark features were built.[32] A railway system connecting Soarano station at one end of the Avenue de l'Indépendance in Antananarive with Toamasina and Fianarantsoa was established in 1897.[33] Beyond these planned spaces, neighborhoods densely populated by working-class Malagasy expanded without state oversight or control.[32]

The city expanded rapidly after World War II;[32] by 1950 its population had grown to 175,000. Roads connecting Antananarivo to surrounding towns were expanded and paved. The first international airport was constructed at Arivonimamo, 45 km (28 mi) outside the city; this was replaced in 1967 with Ivato International Airport approximately 15 km (9 mi) from the city center. The University of Antananarivo was constructed in the Ankatso neighborhood and the Museum of Ethnology and Paleontology was also built. A city plan written in 1956 created suburban zones where large houses and gardens were established for the wealthy. In 1959, severe floods in la ville basse prompted the building of large-scale embankments along the edges of the Betsimitatatra rice fields and the establishment of new ministerial complexes on newly drained land in the Anosy neighborhood.[32]

Post-independence

After independence in 1960, the pace of growth increased further. The city's population reached 1.4 million by the end of the 20th century; in 2013, it was estimated at nearly 2.1 million.[34] Uncontrolled urban sprawl has challenged the city's infrastructure, producing shortages of clean water and electricity, sanitation and public health problems, and heavy traffic congestion.[32] There are more than 5,000 church buildings in the city and its suburbs, including an Anglican and a Roman Catholic cathedral. Antananarivo is the see city of Madagascar's Roman Catholic Archdiocese. The city has repeatedly been the site of large demonstrations and violent political clashes, including the 1972 rotaka that brought down President Philibert Tsiranana and the 2009 Malagasy political crisis, which resulted in Andry Rajoelina replacing Marc Ravalomanana as head of state.[35]

The 2022 Antananarivo floods hit the city in January of that year, causing multiple deaths and significant damage to almost 7,000 houses.[36]

On 26 August 2023, at least 12 people died during a crush incident at the Mahamasina Municipal Stadium, during the opening of Indian Ocean Island Games.[37]

Geography

Antananarivo is situated approximately 1,280 m (4,199 ft) above sea level in the Central Highlands region of Madagascar, at 18.55' South and 47.32' East.[39] The city is located centrally along the north–south axis of the country, and east of the center along the east–west axis. It is 160 km (99 mi) from the east coast and 330 km (210 mi) from the west coast. The city occupies a commanding position on the summit and slopes of a long, narrow, rocky ridge extending north and south for about 4 km (2 mi) and rising to about 200 m (660 ft) above the extensive rice fields to the west.[7]

The official boundaries of the city of Antananarivo encompass an urban area of approximately 86.4 km2 (33.4 sq mi).[39] It was founded 1,480 m (4,860 ft) above sea level at the apex of three hill ranges that converge in a Y form, 200 m (660 ft) above the surrounding Betsimitatatra paddy fields and the grassy plains beyond. The city gradually spread out from this central point to cover the hillsides; by the late 19th century it had expanded to the flat terrain at the base of the hills. These plains are susceptible to flooding during the rainy season; they are drained by the Ikopa River, which skirts the capital to the south and west. The western slopes and plains, being best protected from cyclone winds originating over the Indian Ocean, were settled before those to the east.[7]

Greater Antananarivo is a continuous, urbanized area spreading beyond the city's official boundaries for 9 km (5.6 mi) north to south between Ambohimanarina and Ankadimbahoaka, and 6 km (3.7 mi) west to east between the Ikopa River dike and Tsiadana.[40] The population of the greater Antananarivo area was estimated at 3 million people in 2012; it is expected to rise to 6 million by 2030.[41]

Climate

Under the Köppen-Geiger climate classification system, Antananarivo has a Humid subtropical climate with dry season defined (Cwa, bordering on Cwb), characterized by mild, dry winters and warm, rainy summers.[39] The city receives nearly all of its average annual rainfall between November and April. Frosts are rare in the city; they are more common at higher elevations. Daily mean temperatures range from 20.8 °C (69.4 °F) in December to 14.3 °C (57.7 °F) in July.

Script error: No such module "weather box".

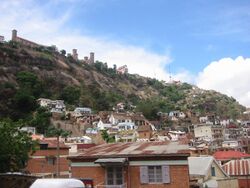

Cityscape

Antananarivo encompasses three ridges that intersect at their highest point. The Manjakamiadana royal palace is located at the summit of these hills and is visible from every part of the city and the surrounding hills. The Manjakamiadina was the largest structure within the rova of Antananarivo; its stone casing is the only remnant of the royal residences to survive a 1995 fire at the site. For 25 years, the roofless shell dominated the skyline; its west wall collapsed in 2004.[45] In 2009, the stone casing had been fully restored and the building was re-roofed. It is illuminated at night. Conservation and reconstruction work at the site is ongoing.[46] The city skyline is a jumble of colorful, historic houses and churches. More recent residential and commercial buildings and family rice fields occupy lower terrain throughout the capital. The Betsimitatatra and other rice fields surround the city.[47]

The city's neighborhoods emerge from historic ethnic, religious, and caste divisions. The assignment of certain neighborhoods to particular noble sub-castes under the Kingdom of Imerina established divisions; the highest-ranking nobles were typically assigned to neighborhoods closest to the royal palace and were required to live in higher elevation portions of the city.[48] During and after French colonization, the expansion of the city continued to reflect these divisions. Today, the haute ville is mainly residential and viewed as a prestigious area in which to live; many of the city's wealthiest and most influential Malagasy families live there.[48] The part of la haute closest to the Rova contains much of the city's pre-colonial heritage and is considered it's historic part.[49] It includes the royal palace, Andafiavaratra Palace—the former residence of Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony, Andohalo—the principal town square until 1897, a cathedral near Andohalo built to commemorate early Malagasy Christian martyrs, the city's most intact historic entrance gate and the 19th-century houses of Merina nobles.[47]

Under the Kingdom of Madagascar, the commoner class (hova) settled at the periphery of the noble districts,[48] gradually spreading along the slopes of the lower hills during the late 19th century. This ville moyenne became increasingly populous under French colonial authority, which targeted them for redesign and development. Today, the neighborhoods in the ville moyenne are densely populated and lively, containing residences, historic sites, and businesses. The neighborhood of Antaninarenina contains the historic Hôtel Colbert, numerous jewelers' shops and other luxury goods stores, and administrative offices. In addition to Antaninarenina, the principal neighborhoods of la ville moyenne are Ankadifotsy on the eastern hills and Ambatonakanga and Isoraka to the west, all of which are largely residential.[49] Isoraka has developed lively nightlife, with houses converted to upscale restaurants and inns. Isoraka also houses the tomb of Prime Minister Rainiharo (1833–1852), whose sons and later Prime Ministers Rainivoninahitriniony and Rainilaiarivony are buried with him.[50] Bordering these neighborhoods are the commercial areas of Besarety and Andravoahangy.[49]

The commercial center of town, Analakely, is located on the valley floor between these two ville moyenne hill ranges.[49] King Andrianampoinimerina established the city's first marketplace[20] on the grounds today occupied by the market's tile-roofed pavilions, constructed in the 1930s.[45] Andrianampoinimerina decreed Friday (Zoma) as market day,[20] when merchants would erect stalls shaded with white parasols, which extended throughout the valley forming what has been called the largest open-air marketplace in the world.[51] The market caused traffic congestion and safety hazards prompting government officials to divide and relocate the Friday merchants to several other districts in 1997.[52] The city's other main commercial and administrative neighborhoods, which spread out from Analakely and extend into the adjacent plain, were established by the French, who drained and filled in the extant rice fields and swampland to create much of the area's design and infrastructure. The Avenue de l'Indépendance runs from the gardens of Ambohijatovo south of the market pavilions, through Analakely to the city's railroad station at Soarano. To the west of Soarano lies the dense commercial district of Tsaralalana; it is the only district to be built on a grid[49] and is the center of the city's South Asian community.[53] Behoririka, to the east of Soarano, is built around a lake of the same name and abuts the sprawling Andravoahangy district at the eastern edge of the city. Antanimena borders Soarano and Behoririka to the north. A tunnel built by the French in the early 20th century cuts through the hillside; it connects Ambohijatovo with Ambanidia and other residential areas in the south of the city.[49]

Since pre-colonial times the lower classes, including those descended from the slave class (andevo) and rural migrants, have occupied the flood-prone lower districts bordering the Betsimitatatra rice fields to the west of the city.[48] This area is connected to Analakely by a tunnel constructed by the French in the early 20th century. The tunnel opens toward Lake Anosy and the national Supreme Court buildings and provides access to the residential neighborhood of Mahamasina and its stadium. The bordering neighborhood of Anosy was developed in the 1950s to house most of the national ministries and the Senate.[49] Anosy, the planned residential district of Soixante-Sept Hectares (often abbreviated to "67") and the neighborhood of Isotry are among the city's most densely populated, crime-ridden and impoverished neighborhoods.[54] Approximately 40 percent of inhabitants with electricity in their homes in the ville basse obtain it illegally by splicing into city power lines. In these areas, houses are more vulnerable to fires, flooding, and landslides, which are often triggered by the annual cyclone season.[55]

Architecture

Before the mid-19th century, all houses and marketplaces in Antananarivo, and throughout Madagascar, were constructed of woods, grasses, reeds, and other plant-based materials viewed as appropriate for structures used by the living. Only family tombs were built from stone, an inert material viewed as appropriate to use for the dead. British missionaries introduced brick-making to the island in the 1820s, and French industrialist Jean Laborde used stone and brick to build his factories over the next few decades. It was not until the royal edict on construction materials was lifted in the 1860s that stone was used to encase the royal palace. Many aristocrats, inspired by the royal palace and the two-story, brick houses with wrapped verandas and divided interior spaces built by British missionaries, copied the British model for their own large homes in the haute ville. The model, known as trano gasy ("Malagasy house"), rapidly spread throughout the Central Highlands of Madagascar, where it remains the predominant house construction style.[56]

Since 1993, the Commune urbaine d'Antananarivo (CUA) has increasingly sought to protect and restore the city's architectural and cultural heritage. In 2005, CUA authorities partnered with the city planners of the Île-de-France to develop the Plan Vert – Plan Bleu strategy for creating a classification system for Zones de Protection du Patrimoine Architectural, Urbain et Paysager, areas of the city benefiting from legal protection and financial support for their historic and cultural heritage. The plan, which is being implemented by the Institut des Métiers de la Ville, prevents the destruction of historic buildings and other structures, and establishes construction codes that ensure new structures follow historic aesthetics. It also provides for awareness-raising campaigns in favor of historic preservation and undertakes projects to restore dilapidated historic buildings and sites. Under this plan, 19th-century sites, like the Ambatondrafandrana tribunal and the second residence of Rainilaiarivony, have been renovated.[41]

Demographics

Antananarivo has been the largest city on the island since at least the late 18th century when its population was estimated at 15,000.[31] By 1810, the population had grown to 80,000 before declining dramatically between 1829 and 1842 during the reigns of Radama I and especially Ranavalona I. Because of a combination of war, forced labor, disease and harsh measures of justice, the population of Imerina fell from 750,000 to 130,000 during this period.[21] In the final years of the Kingdom of Imerina, the population of Antananarivo had recovered to between 50,000 and 75,000; most of the population were slaves who were largely captured in provincial military campaigns.[31] In 1950, Antananarivo's population was around 175,000.[32] By the late 1990s the population of the metropolitan area had reached 1.4 million, and – while the city itself now has a population of 1,275,207 (at the 2018 Census)[3] – with suburbs lying outside the city limits it had grown to almost 2.3 million in 2018.[34] The metropolitan area is thus home to approaching 10 percent of the island's 25.68 million residents. Rural migration to the capital propels this growth; the city's population exceeds that of the other five provincial capitals combined.[31]

As the historic capital of Imerina, Antananarivo is centrally located in the homeland of the Merina people, who comprise about 24 percent of the population and are the largest Malagasy ethnic group. The city's history as the island's major center for politics, culture, and trade has ensured a cosmopolitan mix of ethnic groups from across the island and overseas.[31] Most Antananarivo residents have strong ties to their tanindrazana (ancestral village), where the extended family and typically a family tomb or burial place is located; many older residents leave the city upon retirement to return to their rural area of origin.[57]

Crime

Despite ongoing efforts by the Ministry of Domestic Security, crime has worsened in Antananarivo since 2009. Between 1994 and 1998, the city had an average of eight to twelve police officers for every 10,000 inhabitants; large cities typically have closer to fifteen.[55] Under the mayorship of Marc Ravalomanana (1998–2001), street lights were installed or repaired throughout the city to improve night-time safety. He increased the number of police officers on the streets, leading to a drop in crime.[58] As of 2012[update], the city lacks a comprehensive strategy for reducing crime. The recent increase in crime and the inadequate response from the CUA has prompted the growth of private security firms in the city.[55]

The Antanimora Prison is located in the Antanimora district of the city. The facility has a maximum capacity of 800 inmates and has been reported to be severely overcrowded, at times housing more than 4000 detainees.[59]

Economy

Agriculture is the mainstay of the Malagasy economy. The land is used for the cultivation of rice and other crops, raising of zebu and other livestock, the fabrication of bricks, and other traditional livelihoods. Access to land is guaranteed and protected by law for every resident of the city. The CUA manages requests to lease or purchase land, but demand dramatically outstrips supply, and much of the unallocated land fails to meet the requisite criteria for parceling, such as land where floodwater runoff is diverted. Much of this marginal land has been illegally occupied and developed by land-seeking residents, creating shantytown slums in pockets throughout the lower portions of the city. This uncontrolled development poses sanitation and safety risks to residents in these areas.[39]

Industry accounts for around 13 percent of Madagascar's gross domestic product (GDP) and is largely concentrated in Antananarivo. Key industries include soap production, food and tobacco processing, brewing, textiles, and leather manufacturing, employing around 5.5 percent of the workforce.[48] The city's extensive infrastructure and its role as the economic center of the country make it a favorable location for large businesses. Business owners are drivers of growth for the city; in 2010, 60 percent of all new buildings in the country were located in Antananarivo, most of which were built for commercial purposes. Unemployment and poverty are also growing, fueled in part by an inadequately skilled and unprofessional workforce and the lack of a comprehensive national strategy for economic development since 2009. [55] Formal sector job growth has not kept pace with population growth, and many residents earn their livelihood in the informal sector as street vendors and laborers.[60] Under Ravalomanana, construction in the capital increased sharply; twelve new supermarkets were constructed in two years.[58]

The residents of urban areas—in particular Antananarivo—have been hardest hit by economic downturns and economic policy shifts. The national economic crisis in the mid-1970s and early 1980s, and the World Bank's imposition of a structural adjustment program lowered living standards for the average resident of the city. The end of state subsidies, rapid inflation, higher taxes, widespread impoverishment, and the decline of the middle class was especially evident in Antananarivo, as was the growing wealth of a tiny political and economic elite in the city.[48] In 2007, two-thirds of Antananarivo residents had access to electricity,[61] while ten percent of households owned a scooter, car or another motor vehicle.[62] Running water was installed in fewer than 25 percent of homes, small restaurants, and businesses in 2007, necessitating the collection of water from household wells or neighborhood pumps[61] and the use of outdoor pit toilets detached from the main building. In 2007, 60 percent of households were using shared public latrines.[63] Most homes use charcoal for daily cooking; stocks of charcoal and rice are kept in the kitchen.[64] The average city household spends just under half of its budget on food.[65] Owing to its increasingly high cost, consumption of meat by city residents has sharply declined since the 1970s; the urban poor eat meat on holidays only once or twice a year.[66]

Culture

In Antananarivo and throughout the highlands, Merina and Betsileo families practice the famadihana, an ancestor reburial ceremony. This ceremony typically occurs five to seven years after the death of a relative and is celebrated by removing the relative's lamba-wrapped remains from the family tomb, rewrapping it with fresh silk shrouds and returning it to the tomb. Relatives, friends, and neighbors are invited to take part in the music, dancing, and feasting that accompanies the event. The famadihana is costly; many families sacrifice higher living standards to set aside money for the ceremony.[67]

Historic sites and museums

The city has numerous monuments, historic buildings, sites of significance, and traditions related to the customs and history of the Central Highlands people.[55] The city skyline is dominated by the Rova of Antananarivo. The nearby Andafiavaratra Palace was the home of 19th-century Prime Minister Rainilaiarivony and contains a museum featuring historic artifacts of the Kingdom of Imerina, including items saved from the fire at the Rova. Downhill from the palaces is Andohalo square, where Merina kings and queens delivered speeches to the public. Tsimbazaza Zoo displays many of the island's unique animal species and a complete skeleton of the extinct elephant bird. Other historic buildings include the Ambatondrafandrana tribunal where Ranavalona I dispensed judgment, the second residence of Rainilaiarivony with its indigenous medicinal plant garden,[41] the recently renovated Soarano railroad station, four late 19th-century memorial churches built to commemorate early Malagasy Christian martyrs, the tomb of Prime Minister Rainiharo, and the early 20th century pavilions of the Analakely market. Open-air markets include Le Pochard and the artisan market at Andravoahangy. The Museum of Art and Archaeology in the Isoraka neighborhood features exhibits on the history and cultures of Madagascar's diverse ethnic groups.[71] The Pirates Museum in Tsaralalàna explains the history of maritime pirates and the story of the pirates in Madagascar and their mysterious Republic of Libertalia.[72]

Arts

The arts scene in Antananarivo is the largest and most vibrant in the country. Madagascar's diverse music is reflected in the many concerts, cabarets, dance clubs, and other musical venues throughout Antananarivo. In the dry season, outdoor concerts are regularly held in venues including the Antsahamanitra amphitheater and Mahamasina Stadium.[73] Concerts and nightclubs are attended mainly by young people of the middle to upper classes who can afford the entrance fees.[73] More affordable are performances of traditional vakindrazana or Malagasy operettas at Isotry Theater and hira gasy at the city's outdoor cheminots theater or Alliance française; these performances are more popular with older and rural audiences than among urban youth.[74] Nightlife is the most animated in the ville moyenne neighborhoods of Antaninarenina, Tsaralalana, Behoririka, Mahamasina, and Andohalo.[75]

The Palais des Sports in the Mahamasina neighborhood is the country's only indoor performance space built to international standards. It was built in 1995 by the Government of China; it regularly hosts concerts, dance, and other arts performances, expositions, and novelty events like monster truck rallies. The city lacks a dedicated classical music performance space, and concerts by international artists are infrequent. Performances of classical, jazz, and other foreign musical genres, modern and contemporary dance, theater, and other arts occur at cultural arts centers funded by foreign governments or private entities. Among the best-known of these is the Centre Culturel Albert Camus and Alliance française d'Antananarivo, both funded by the French government.[73] the Cercle Germano-Malgache, a branch of the Goethe-Institut funded by the German government;[76] The American Center is funded by the United States government.[77] Antananarivo has two dedicated cinemas, the Rex and the Ritz, both of which were built in the colonial era. These venues do not show international releases but occasionally screen Malagasy films or are used for private events and religious services.[73]

Sports

Rugby Union is considered the national sport of Madagascar.[78] The national rugby team is nicknamed the Makis after the local word for the indigenous ring-tailed lemur. The team trains and plays domestic matches at Maki Stadium in Antananarivo. Constructed in 2012, the stadium has a capacity of 15,000 and houses a gym and administrative offices for the team.

Several soccer teams are based in Antananarivo; AS Adema Analamanga and Ajesaia are associated with the Analamanga region; USCA Foot is associated with the CUA and the AS Saint Michel has been affiliated since 1948 with the historic secondary school of the same name. All four teams train and play local games in Mahamasina Municipal Stadium, the largest sporting venue in the country. The men's basketball teams Challenger and SOE (Équipe du Stade olympique de l'Emyrne) are based in Antananarivo and play in the Palais des Sports at Mahamasina.[79]

The sports facilities of the University of Antananarivo were used to host the official 2011 African Basketball Championship.

Places of worship

Among the places of worship, they are predominantly Christian churches and temples : Church of Jesus Christ in Madagascar (World Communion of Reformed Churches), Malagasy Lutheran Church (Lutheran World Federation), Assemblies of God, Association of Bible Baptist Churches in Madagascar (Baptist World Alliance), Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Antananarivo (Catholic Church).[80] There are also Muslim mosques.

Government

Antananarivo is the capital of Madagascar, and the federal governance structures, including the Senate, National Assembly, the Supreme Court, and the presidential office are housed there. The main presidential offices are located 15 km (9.3 mi) south of the city. The city hosts diplomatic missions of 21 countries.[81]

The CUA is divided into six numbered arrondissements (administrative sub-districts); it has historically been administered by an elected mayor and associated staff.[39] Since the 2009 political crisis, in which the Mayor of Antananarivo, Andry Rajoelina, unconstitutionally seized power as head of state, the CUA has been administered by a délégation spéciale (special delegation) composed of a president and de facto mayor with the support of two vice presidents, all of whom are appointed by the president.[82] The position of President of the Special Delegation has been held by Ny Hasina Andriamanjato since March 2014.[83]

The mayoral administration of the CUA is empowered to govern the city with de jure autonomy; a wide range of mechanisms have been established to facilitate governance, although they are of limited effectiveness. An urban master plan guides major policies for city management but personnel within the mayoral office commonly lack the urban planning and management ability to effectively implement the plan in response to long-term and immediate needs. This challenge is compounded by the high turnover rate of mayors and staff that frequently disrupts initiatives begun by previous CUA administrations.[39] A mayor under former President Didier Ratsiraka created "red zones"; areas where public gathering and protests were prohibited. On 28 June 2001, Ravalomanana abolished these areas, liberalizing freedom of assembly.[84]

Antananarivo has suffered from debt and mismanagement. The CUA estimated in 2012 that the cost of running the city to international standards would reach US$100 million annually, while annual revenues average around $12 million. In good years, the CUA can reserve $1–2 million to spend on city improvement projects.[41] By 2008, the city's treasury had accumulated 8.2 billion Malagasy ariary—approximately US$4.6 million—in debts under previous mayors.[85] In 2008, water was cut off at public pumps, and there were regular brownouts of city street lights because of 3.3 million ariary of unpaid debts to the Jirama public utility company by the City of Antananarivo. In response, Mayor Rajoelina undertook an audit that identified and sought to address long-standing procedural irregularities and corruption in the city's administration.[86] The CUA continues to be challenged by a shortage of revenues relative to its expenses caused by the high cost of retaining a large number of CUA personnel, weak structures for managing revenues from public rents and inadequate collection of tax revenues from city residents and businesses.[39]

Twin towns and sister cities

Antananarivo has established sister city agreements with four cities. The city was twinned with Yerevan, Armenia in 1981.[87] The city is also twinned with Vorkuta, Russia;[88] Suzhou, China;[89] and Montreal , Canada.[90] A sister city relationship between Antananarivo and Nice, France, established in 1962, is not active.[91] In 2019, the Mayor of the Commune Urbaine Antananarivo was inviting the City of Kota Kinabalu in Malaysia to enter into a sister relationship with the City of Antananarivo.[92]

Education

Most of Madagascar's public and private universities are located in Antananarivo.[93] This includes the country's oldest higher education institute, the College of Medicine established under the Merina monarchy and the University of Antananarivo, established under the French colonial administration. The Centre National de Télé-Enseignement de Madagascar (CNETMAD) is located in Antananarivo.[94] The city hosts many private pre-primary, primary and secondary schools and the national network of public schools.[95] The city houses multiple French international schools, including Lycée Français de Tananarive, Lycée La Clairefontaine, Lycée Peter Pan,[96] and École de l'Alliance française d'Antsahabe.[97] It also houses an American school, American School of Antananarivo, and a Russian school, the Russian Embassy School in Antananarivo (Russian: основная общеобразовательная школа при Посольстве России на Мадагаскаре).[98]

The nation's most prestigious dance school, K'art Antanimena, is located in Antananarivo. Other major dance schools based in the city include Le Club de Danse de l'Université Catholique de Madagascar, Club de danse Kera arts'space à Antanimena and Le Club Mills.[79]

Health and sanitation

In general, the availability and quality of health care are better in Antananarivo than elsewhere in Madagascar, although it remains inadequate across the country relative to that in more developed countries. One of Madagascar's two medical schools is located in Antananarivo; most medical technicians and specialists are trained there.[99] Neonatal[100] and antenatal care are significantly better in Antananarivo than elsewhere on the island.[101] Despite the presence of facilities and trained personnel, the high cost of health care places it beyond the reach of most residents of Antananarivo. Pharmaceuticals are imported, making them particularly unaffordable; traditional herbal medicines remain popular and are readily available in local markets frequented by most of the population.[102]

The large population in Antananarivo and the high density of its residential zones pose challenges to public health, sanitation, and access to clean drinking water. Processing and disposal of industrial and residential waste are inadequate. Wastewater is often discharged directly into the city's waterways. Air pollution from vehicle exhaust, residential coal-burning stoves, and other sources is worsening.[55] While the city has set up clean water pumps, they remain inadequate and are not distributed according to population density, with poor access in the poorest and most populous parts of the city.[55] Antananarivo is one of the two urban areas in Madagascar where bubonic plague is endemic.[103]

In 2017, Antananarivo was ranked as the 7th worst city for particulate-matter air pollution in the world.[104][105]

These problems were diminished but not eliminated under the mayoral administration of Marc Ravalomanana, who prioritized sanitation, security, and public administration. He obtained funds from international donors to establish garbage collection and disposal systems, restore dilapidated infrastructures such as roads and marketplaces, and replanted public gardens.[106] To improve sanitation in the city, he constructed public latrines in densely populated and highly frequented areas.[107]

Transport and communications

The majority of the city's residents move about Antananarivo on foot. The CUA sets and enforces rules that govern a system of 2,400 franchised private minibuses running on 82 numbered routes throughout the city. An additional 2,000 minibuses managed by the Ministry of Transportation run along 8 lines into the neighboring suburbs. These interlinked bus systems served around 700,000 passengers each day.[41] These minibuses often fail to meet safety standards or air quality requirements and are typically overcrowded with passengers and their cargo. Police and gendarmes assist in regulating traffic at peak periods in the morning and evening, or around special events and holidays. Private licensed and unlicensed taxis are common; most vehicles are older Renaults or Citroens. Newer vehicles congregate near hotels and other locales frequented by foreigners willing or able to pay higher prices for better services.[41]

The city is encircled by a ring road and connected by direct routes nationales (national highways) to Mahajanga, Toliara, Antsirabe, Fianarantsoa and Toamasina. Branches and feeder roads from these major highways connect the city to the national road network. Antananarivo was connected by train to Toamasina to the east and Manakara to the southeast via Antsirabe and Fianarantsoa, but since 2019 passenger trains have not been operated anymore. The city's principal railway station is centrally located at Soarano at one end of the Avenue de l'Indépendance. Ivato International Airport is located approximately 15 kilometres (9 miles) from the center of the city, connecting Antananarivoto to all national airports. Ivato is the hub of the national airline Air Madagascar,[32] and is the only airport on the island hosting long-haul carriers. Direct flights connect Antananarivo to cities in South Africa and Europe.[108]

Government television and radio broadcasting centers, and the headquarters of numerous private stations are located in Antananarivo. Eighty percent of households in Antananarivo own a radio; the medium is popular across social classes. Stations like Fenon'ny Merina appeal to Merina listeners of all ages by playing traditional and contemporary music of the highlands region. Youth-oriented stations play a blend of Western artists and Malagasy performers of Western genres, as well as fusion and coastal musical styles. Evangelical broadcasts and daily international and local news are available in Malagasy, French, and English.[109] Forty percent of Antananarivo residents own a television receiver.[110] All major Malagasy newspapers are printed in the city and are widely available. Communications services in Antananarivo are the best in the country. Internet and mobile telephone networks are readily available and affordable, although service disruptions occur periodically. The national postal service is headquartered in Antananarivo, and private international shipping companies like FedEx, DHL Express, and United Parcel Service provide services to the city.[111]

Notable people

- Lucile Allorge (born 1937), botanist

Notes

- ↑ Institut National de la Statistique Madagascar (web)

- ↑ "Madagascar: Regions, Cities & Urban Communes - Population Statistics, Maps, Charts, Weather and Web Information". https://www.citypopulation.de/en/madagascar/cities/.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Institut National de la Statistique, Madagascar.

- ↑ "Dictionary.com: Antananarivo". http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/antananarivo.

- ↑ "Dictionary.com: Tananarive". http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/tananarive?s=t.

- ↑ Oxford Dictionary: Tananarive (American English)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Shillington 2004, p. 158.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Callet 1908, pp. 654–656.

- ↑ Government of France 1898, pp. 918–919.

- ↑ Desmonts 2004, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Roman Adrian Cybriwsky, Capital Cities around the World: An Encyclopedia of Geography, History, and Culture, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2013, p. 15

- ↑ Callet 1908, p. 522.

- ↑ Callet 1908, pp. 563–565.

- ↑ Acquier 1997, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Oliver 1886, p. 221.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Royal Hill of Ambohimanga". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2012. https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/950.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ Berg, Gerald M. (1988). "Sacred Acquisition: Andrianampoinimerina at Ambohimanga, 1777–1790". The Journal of African History 29 (2): 191–211. doi:10.1017/S002185370002363X.

- ↑ Campbell 2012, p. 454.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 34.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Campbell, Gwyn (October 1991). "The state and pre-colonial demographic history: the case of nineteenth-century Madagascar". Journal of African History 23 (3): 415–445. doi:10.1017/S0021853700031534.

- ↑ Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 165.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Nativel 2005, pp. 76–66.

- ↑ Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 167.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Rakotoarilala, Ninaivo (15 January 2013). "D'Antaninarenina à Ambondrona: Andry Rajoelina revisite son adolescence" (in fr). Madagascar Tribune. http://www.madagascar-tribune.com/Andry-Rajoelina-revisite-son,18358.html.

- ↑ Oliver 1886, p. 78.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, p. 327.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, pp. 122–124.

- ↑ Ade Ajayi 1998, p. 439.

- ↑ Nativel 2005, p. 25.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 31.3 31.4 Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 114.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 Shillington 2004, p. 159.

- ↑ McLean Thompson & Adloff 1965, p. 271.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 "2005 population estimates for cities in Madagascar". http://www.mongabay.com/igapo/2005_world_city_populations/Madagascar.html.

- ↑ "AFP: Hundreds protest Madagascar mayor's sacking". 4 February 2009. https://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5ifdczZtXnRO9VQb3h7Xm5hDhdxeA.

- ↑ "10 killed by floods in Madagascar". Africanews. 18 January 2022. https://www.africanews.com/2022/01/18/10-killed-by-floods-in-madagascar/.

- ↑ "Several dead in Madagascar stadium crush at opening of Indian Ocean Island Games" (in en). 2023-08-26. https://www.france24.com/en/africa/20230826-several-dead-in-madagascar-stadium-crush-at-opening-of-indian-ocean-island-games.

- ↑ London Missionary Society, ed (1869). Fruits of Toil in the London Missionary Society. London: John Snow & Co.. p. 44. https://archive.org/details/fruitsoftoilinth17115gut. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 39.3 39.4 39.5 39.6 UN-Habitat 2012, p. 7.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 153.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 41.4 41.5 "Actes du séminaire international sur le développement urbain" (in fr). Commune Urbaine d'Antananarivo. March 2012. http://www.jeuneafrique.com/Article/LIN14017ravaleuqilb0/.

- ↑ "Antananarivo Climate Normals 1991–2020". World Meteorological Organization Climatological Standard Normals (1991–2020). National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. https://www.nodc.noaa.gov/archive/arc0216/0253808/1.1/data/0-data/Region-1-WMO-Normals-9120/Madagascar/CSV/ANTANANARIVO_67085.csv.

- ↑ "Antananarivo Climate Normals 1961–1990 (Sunhours)". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. ftp://ftp.atdd.noaa.gov/pub/GCOS/WMO-Normals/TABLES/REG__I/MG/67083.TXT.

- ↑ "Antananarivo Climate Normals 1981–2010 (Humidity)". .pogodaiklimat. http://www.pogodaiklimat.ru/climate2/67083.htm.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 297.

- ↑ "Patrimoine – La première phase des travaux terminée: Le "rova" renaît de ses cendres" (in fr). Le Quotidien de la Réunion et de l'Océan Indien (Antananarivo, Madagascar). 2 December 2010.

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 Hellier, Chris (Summer 1999). "Madagascar: Antananarivo – Love Me, Love Me Not". Travel Africa Magazine. http://www.travelafricamag.com/index2.php?option=com_content&do_pdf=1&id=106.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 48.2 48.3 48.4 48.5 Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 12.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 49.4 49.5 49.6 Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 16.

- ↑ Nativel & Rajaonah 2009, p. 126.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 312.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 79.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 221.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 232.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 55.4 55.5 55.6 UN-Habitat 2012, p. 8.

- ↑ Andriamihaja, Nasolo Valiavo (5 July 2006). "Habitat traditionnel ancien par JP Testa (1970), Revue de Madagascar: Evolution syncrétique depuis Besakana jusqu'au trano gasy" (in fr). L'Express de Madagascar (Antananarivo). http://www.madatana.com/article-trano-gasy.php.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 171.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 "Madagascar's presidential election: Will the yoghurt tycoon take over?". The Economist. 20 December 2001. http://www.economist.com/node/917556.

- ↑ "OHCHR | Humanizing the prison world: A diplomatic victory in Madagascar" (in en-US). https://www.ohchr.org/EN/NewsEvents/Pages/ImprovingprisonconditionsinMadagascar.aspx.

- ↑ Appiah & Gates 2010, p. 115.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 275.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 317.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 279.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, pp. 267–268.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 106.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 104.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 141.

- ↑ Tacchi, A. (1892). Sibree, J.; Baron, R.. eds. King Andrianampoinimerina, and the Early History of Antananaviro and Ambohimanga, in The Antananarivo Annual and Madagascar Magazine (Vol. IV 1889–1892 ed.). London: Press of the L.M.S.. pp. 486–487. https://books.google.com/books?id=OoIcAAAAMAAJ. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ↑ Brown, Mervyn (2006). A History of Madagascar. Princeton: Markus Wiener Publishers. pp. 163, 186. ISBN 9781558762923.

- ↑ Ellis, William (1870). The Martyr Church: a Narrative of the Introduction, Progress and Triumph of Christianity in Madagascar. London: John Snow and Co.. p. 172. https://archive.org/details/martyrchurchana00elligoog. Retrieved 27 July 2019.

- ↑ Bradt & Austin 2011, pp. 162–163.

- ↑ "Piratenmuseum Madagaskar - Musée de Pirates Madagascar - Pirate Museum Madagascar". https://piratenmuseum.ch/.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 73.3 Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 69.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 70.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 180.

- ↑ "Qui Sommes Nous?". Goethe Institut Antananarivo. 2013. http://www.goethe.de/ins/mg/ant/uun/frindex.htm.

- ↑ Rakotoharimanana, Volana; Saraléa, Judicaëlle (7 January 2012). "American center: Le high tech au service de la culture" (in fr). L'Express de Madagascar. http://www.lexpressmada.com/5117/american-8200-center-madagascar/30745-le-8200-high-8200-tech-8200-au-8200-service-8200-de-8200-la-8200-culture.html.

- ↑ "Madagascar take Sevens honours". International Rugby Board. 23 August 2007. http://www.irb.com/newsmedia/regional/newsid=53025.html.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 "Association Sportive Malgache". Sport Madagascar. 2009. http://www.sport-madagascar.com/association-sportive-malgache.html.

- ↑ J. Gordon Melton, Martin Baumann, Religions of the World: A Comprehensive Encyclopedia of Beliefs and Practices, ABC-CLIO, USA, 2010, p. 1768

- ↑ "Madagascar: Embassies and Consulates". Embassypages.com. 22 August 2014. http://www.embassypages.com/madagascar.

- ↑ Rakotomalala, Mahefa (3 December 2013). "Commune d'Antananarivo: Olga Rasamimanana nommée vice-pds" (in fr). L'Express de Madagascar. http://www.lexpressmada.com/commune-d-antananarivo-madagascar/48620-olga-rasamimanana-nommee-vice-pds.html.

- ↑ Radasimalala, Vonjy (21 March 2014). "Antananarivo – Les neuf défis d'Andriamanjato" (in fr). L'Express de Madagascar. http://www.lexpressmada.com/blog/actualites/antananarivo-les-neuf-defis-dandriamanjato-7539.

- ↑ Vivier 2007, p. 13.

- ↑ Randria, N. (22 December 2007). "Andry Rajoelina hérite de 41 milliards fmg de dettes" (in fr). Madagascar Tribune. http://www.madagascar-tribune.com/Andry-Rajoelina-herite-de-41,3713.html.

- ↑ Randria, N. (7 January 2008). "La CUA et les coupures d'eau et d'électricité: Antananarivo est-elle sanctionnée?" (in fr). Madagascar Tribune. http://www.madagascar-tribune.com/Antananarivo-est-elle-sanctionnee,3929.html.

- ↑ "Yerevan – Twin Towns and Sister Cities". Yerevan Municipality. 2013. http://www.yerevan.am/en/partner/sister-cities/.

- ↑ Stoiljkovic, Milena (28 April 2013). "World Sister Cities Day". In Serbia. http://inserbia.info/news/2013/04/world-sister-cities-day/.

- ↑ "Sister Cities". Chinese-African People's Friendship Association. 2014. http://www.capfa.org.cn/en/city_js.asp?id=354&fatherid=297.

- ↑ "Villes-jumelages de Montréal" (in fr). Vivre au Québec. 2014. http://www.vivre-au-quebec.com/montreal-city/villes-jumelages-de-montreal.html.

- ↑ "Villes jumelées avec la Ville de Nice" (in fr). Ville de Nice. http://www.nice.fr/Collectivites/La-municipalite/Villes-jumelees-avec-la-Ville-de-Nice.

- ↑ "Madagascar Council wants to bring more tourists to Sabah". Daily Express. 27 March 2019. http://www.dailyexpress.com.my/news/132966/madagascar-council-wants-to-bring-more-tourists-to-sabah/.

- ↑ "Liste des institutions supérieures dont les offers de formation ont reçu l'habilitation du MESUPRES" (in fr). MESUPRES. 2014. http://www.mesupres.gov.mg/IMG/pdf/LISTE_DES_INSTITUTIONS_SUPERIEURES_HABILITEES_PAR_LE_MESUPRES_17_fevrier_2014.pdf.

- ↑ "CNTEMAD – Centre National du Télé-Enseignement de Madagascar". http://www.cntemad.mg/.

- ↑ "Enquête Nationale sur le Suivi des indicateurs des Objectifs du Millénaire pour le Développement (ENSOMD)" (in fr). INSTAT. 2014. http://www.instat.mg/pdf/ensomd-2012-2013_2.pdf.

- ↑ "Lycée Peter Pan ." AEFE. Retrieved on 5 July 2018.

- ↑ "École de l'Alliance française d'Antsahabe ." AEFE. Retrieved on 5 July 2018.

- ↑ Home . Russian Embassy School in Antananarivo. Retrieved on 6 July 2018.

- ↑ Sharp & Kruse 2011, p. 64.

- ↑ Sharp & Kruse 2011, p. 74.

- ↑ Sharp & Kruse 2011, p. 40.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 107.

- ↑ Sharp & Kruse 2011, p. 19.

- ↑ "Air Pollution Ranking in 32 Cities â€" How Does Yours Measure Up? (State of Pollution Series)" (in en-US). 2017-08-11. https://cleantechnica.com/2017/08/11/air-pollution-ranking-32-cities-measure/.

- ↑ Madagasikara, Redaction Midi (October 31, 2018). "Rapport de l'OMS : Antananarivo, parmi les villes les plus polluées au monde – Midi Madagasikara" (in fr-FR). http://www.midi-madagasikara.mg/a-la-une/2018/10/31/rapport-de-loms-antananarivo-parmi-les-villes-les-plus-polluees-au-monde/.

- ↑ Geslin, Jean-Dominique (15 January 2007). "Ravalomanana le PDG de la République" (in fr). Jeune Afrique. http://www.jeuneafrique.com/Article/LIN14017ravaleuqilb0/.

- ↑ Robinson, Katya (21 August 2000). "AFRICA / Madagascar Magician / But some ask if cleanup campaign by capital's mayor is only skin deep". SFGate. http://www.sfgate.com/politics/article/AFRICA-Madagascar-Magician-But-some-ask-if-2743041.php.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 65.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, pp. 275–276.

- ↑ Fournet-Guérin 2007, p. 276.

- ↑ Bradt & Austin 2011, pp. 105, 159.

References

- Acquier, Jean-Louis (1997) (in fr). Architectures de Madagascar. Berlin: Berger-Levrault. ISBN 978-2-7003-1169-3.

- Ade Ajayi, Jacob Festus (1998). General history of Africa: Africa in the nineteenth century until the 1880s. Paris: UNESCO. ISBN 978-0-520-06701-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=VC7kKcXdDhkC. Retrieved February 3, 2011.

- Appiah, Anthony; Gates, Henry (2010). Encyclopedia of Africa, Volume 1. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-533770-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=A0XNvklcqbwC.

- Bradt, Hilary; Austin, Daniel (2011). Madagascar (10th ed.). Guilford, Connecticut: The Globe Pequot Press Inc. ISBN 978-1-84162-341-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=uTRPnMlOcwgC.

- Callet, François (1908) (in fr). Tantara ny andriana eto Madagasikara (histoire des rois). Antananarivo: Imprimerie catholique.

- Campbell, Gwyn (2012). David Griffiths and the Missionary "History of Madagascar". Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-20980-0. https://books.google.com/books?id=7pDNL4apVpgC.

- Desmonts (2004) (in fr). Madagascar. New York: Editions Olizane. ISBN 978-2-88086-387-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=x57t6B-wo6kC.

- Fournet-Guérin, Catherine (2007). Vivre à Tananarive: géographie du changement dans la capitale malgache. Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-84586-869-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=U_NHlyeI3mcC.

- Government of France (1898). "L'habitation à Madagascar" (in fr). Colonie de Madagascar: Notes, reconnaissances et explorations. 4. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Imprimerie Officielle de Tananarive. https://books.google.com/books?id=Jp3FAAAAMAAJ.

- McLean Thompson, Virginia; Adloff, Richard (1965). The Malagasy Republic: Madagascar today. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0279-9.

- Nativel, Didier (2005) (in fr). Maisons royales, demeures des grands à Madagascar. Antananarivo, Madagascar: Karthala Éditions. ISBN 978-2-84586-539-6. https://books.google.com/books?id=8IOZLvSrspIC.

- Nativel, D.; Rajaonah, F. (2009) (in fr). Madagascar revisitée: en voyage avec Françoise Raison-Jourde. Paris: Karthala Editions. ISBN 978-2-8111-0174-9. https://books.google.com/books?id=6NHOFJJHOc0C.

- Oliver, Samuel (1886). Madagascar: An Historical and Descriptive Account of the Island and its Former Dependencies. 1. New York: Macmillan and Co. https://books.google.com/books?id=lKtBAAAAIAAJ.

- Shillington, Kevin (2004). Encyclopedia of African History, Volume 1. New York: CRC Press. ISBN 978-1-57958-245-6.

- Sharp, Maryanne; Kruse, Joana (2011). Health, Nutrition, and Population in Madagascar, 2000–09. New York: World Bank. ISBN 978-0-8213-8538-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=CzyjH7BgdlcC.

- UN-Habitat (2012) (in fr). Madagascar: Profil urbain d'Antananarivo. Nairobi, Kenya: UNON. ISBN 978-92-1-132472-3. http://www.unhabitat.org/pmss/getElectronicVersion.aspx?nr=3371&alt=1. Retrieved December 7, 2013.

- Vivier, Jean-Loup (2007) (in fr). Madagascar sous Ravalomanana: La vie politique malgache depuis 2001. Paris: Editions L'Harmattan. ISBN 978-2-296-18554-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=4rGifG26P4IC.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Antananarivo. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Antanànarìvo. |

- Antananarivo Renivohitra – official website (in French) (archived 30 March 2007)

"Tananarivo". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

"Tananarivo". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

|