Place:Aybak, Samangan

Aybak سمنگان | |

|---|---|

Town | |

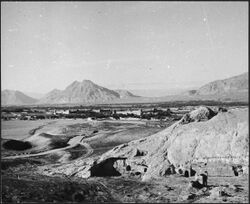

Overview of Aybak valley | |

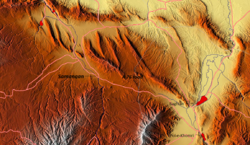

Location of Aybak. Click to see. | |

| Coordinates: [ ⚑ ] : 36°15′55″N 68°1′0″E / 36.26528°N 68.016667°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Samangan |

| District | Aybak |

| Elevation | 959 m (3,146 ft) |

| Population (2012) | |

| • Total | 9,958 |

| Time zone | + 4.30 |

Aybak (Aibak or Haibak; previously Eukratidia (Ancient Greek:);[1] historically known as Samangan)[2] is a provincial town, medieval caravan stop, and the headquarters of the Samangan Province in the district of the same name in the northern part of Afghanistan. As an ancient town and major Buddhist centre during the 4th and 5th centuries under the then Kushan rulers, it has the ruins of that period at a place known now as Takht-i-rustam, which is located on a hill above the town.[3]

Due to its location, Haibak has been influenced by Buddhist, Islamic and Turkic and Persian peoples. In the past, it was significant because of its position on the main line of communication between Kabul and Afghan Turkestan.

In 2021, the Taliban gained control of the city during the 2021 Taliban offensive.

History

The earliest known history is linked to the identification of the place by Ptolemy as the place of the Varni or Uarni and the fortified city of Samangan on the banks of the Khulm River, identical to the city on the Dargydus River, south east of Zariaspa/Balkh. The ruins found here establish the city's founding by Eucratides I, the King of Bactria. It was then known as Eukratidia, the size of the present Khulm city.[4]

Historicity of the town is dated to the Kushan Dynasty reign during the 4th and 5th centuries when it was a famous Buddhist centre. Witness to this period is seen now in the form of ruins at a place called the Takht-e-Rostam, which is located 3 km from the town on a hilltop. Arabs and Mongols came to this place when it was already famous as a Buddhist religious centre.[3]

Takht-i-rustam is a historical place where ruins of Buddhist religious culture could be seen. The Buddhist stupa here in the form of a mound, located on the hilltop, represents the earliest link to the evolution of Buddhist architecture.[3]

Aibak was the name given to this place when during the medieval period, caravans used to stop here.[3]

On October 23, 2003, during the war, rebels fired rockets at a pickup truck ferrying passengers to Haibak, which killed ten people.[citation needed]

In 2021, the Taliban launched a nationwide military offensive coinciding with the withdrawal of United States troops. Aybak was captured on 9 August 2021, becoming the sixth provincial capital to fall to the Taliban after a weekend offensive.[5]

The bombing of a school in December 2022 killed 17 people.[6]

Historical heritage

Samangan has one of the well-known archaeological sites in Afghanistan, in the Takth i Rostam and the adjacent Buddhist caves and stupas on top of a hill, north of Hindu Kush passes. At this location, caves were hewn out of rocks and inhabited by Buddhists. The Buddhist stupa here is in the form of a mound. It represents the earliest link to the evolution of Buddhist architecture in Afghanistan. Another heritage site is the Hazar Sumuch District which is about 10 km away from the town.

- Takht-i Rustam

Takht-i Rustam (Haibak), literal meaning "the throne of Rustam", named after Rustam, a mythological warrior in Persian mythology, is a hilltop settlement. It is dated to the 4th and 5th centuries of the Kushano-Sassanian period, which is corroborated by archaeological, architectural and numismatic evidence. It is located 3 km to the southwest of Samangan town. It is the location of a stupa-monastery complex which is fully carved into the mountain rock. The monastery of the major Buddhist tradition of Theravada Buddhism, has five chambers, two are sanctuaries and one is a domed ceiling with an intricate lotus leaf beautification. In the adjacent hill is the stupa, which has a harmika, with several caves at its base. Above one of the caves, there is square building with two conference halls, one is 22 metres square and the other is circular. In one of these caves, Archaeological excavations have revealed a cache of Ghaznavid coins.[7][8] The Buddhist temples near the Takht are 10 numbers known locally as Kie Tehe.[9]

- Hazar Sumuch District

Hazar Sumuch District is another ancient Buddhist centre in north central Afghanistan where several caves have been found and in one of these caves a Buddhist stupa has been carved.[10]

Legend

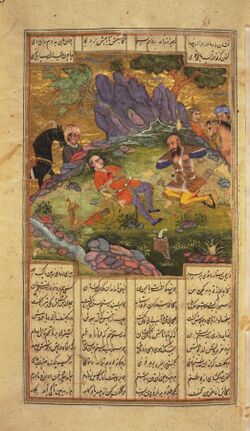

A hoary legend links Samangan to the famous epic story of Rostam and Sohrab. Rostam (meaning hero of the World), a valiant hero of Iran, was on a hunting visit to the Samangan area. He took rest at a place near the Samangan area, in the village of Shaihabad. During this time, his horse was stolen under a plan engineered by the local King, who was impressed by the valour of Rustam. The local king wanted to have Rostam as his ally. When Rostam finds out that his horse, named Rakhsh, had been stolen, he became furious and went in search of the horse and the search led him to the Samangan town. When he reached the outskirts of the town, the King of Samangan and his entourage came to greet him. Rostam then threatened the Samangan King with dire consequences if his horse was not found, as the horse's hoofprints had been tracked up to the village. The local king, however, assuaged Rostam and invited him to his palace as his honoured guest and entertains him lavishly. He also promised Rostam that he would arrange to send search parties to find his horse. While in the palace, the King's daughter Tamina met him and falls in love with Rustam. Rustam also fell in love with her. With the approval of the king and the people of Samangan, the local ruler's beautiful daughter Tamina married Rustam. The king was pleased with this development and he then arranged to find the horse of Rostam. Rostam then returned to Iran, his home country. Before taking leave of his wife he gave her an onyx t[clarification needed] that was tied to his arm. He gave it to her, and said:

| “ | Cherish this jewel, and if Heaven cause thee to give birth unto a daughter, fasten it within her locks, and it will shield her from evil; but if it be granted unto thee to bring forth a son, fasten it upon his arm, that he may wear it like his father. And he shall be strong as Keriman, of stature like unto Sam the son of Neriman, and of grace of speech like unto Zal, my father. | ” |

Both were sorrowful at the separation from each other. Their son was later born to Tamina in Samangan, who was named as Sohrab.[11][12][13]

Tahmineh brought up her son with great dedication and taught him all the skills of warfare and he became very strong. She also told him about his father Rostam and his forefathers and their valiant achievements as warriors in Iran. She also gave him the gifts that his father had sent him. She advised him to be wary of Afrasiyab of Turan who was father's foe. After knowing his ancestry and about his brave father, Sohrab decided to invade Iran. He also promised his mother that she would be the queen of Iran. As he rode on a horse which was the foal of Rakshak, his father's horse, he thought the tidings were good. However, as he moved to wage war against Iran he encountered his father on the battlefield. His father had been kept totally unaware of his son's identity by Afrasiyab who wanted father and son to fight each other. Before Sohrab led his army against Iran, Afrasiyab had beguiled him to join him in the war, with gifts with messages praising Sohrab for his intent to invade Iran and told him how that "if Iran be subdued the world would henceforth know peace, for upon his own head would he place the crown of the Kaianides; and Turan, Iran, and Samengan should be as one land." There was deceit and false information given about Rostam. Both were unaware of each other's identity and relationship when they faced each other on the battlefield. In the fierce battle that took place between father and son Sohrab was mortally wounded. When Sohrab was wounded he announced his identity to Rostam and on hearing this Rostam was overtaken by intense grief and threw away his sword. Sohrab also was grief-stricken upon knowing that it was his father whom he had faced in the war and who had wounded him mortally. He then showed his onyx symbol that was tied to his armour. Rostam realized that it was the onyx which he had given to his wife and that he had really slain his own son. Kaykavous, the king of Iran, delayed giving Rostam the healing potion (Noush Daru) to save Sohrab as he feared losing his power to the alliance of the father and the son.[11][12][13]

Geography

The town is located on the banks of the Khulm River valley formed below the junction of Hindu Kush Mountains and the Central Asian Steppe. The valley has very fertile agricultural land and is characterised by rolling green fields and hills at the sides.[3] The A76 highway from Kabul -Mazar-e-Sharif to Badakhshan passes through Samangan town and goes through the bazaar and the main town square. The nearest major cities are Mazar-e-Sharif and Baghlan. The town is known for its large Uzbek population and the well-known Uzbek leader of the province, General Dostum's pictures, are on display in the town.[3]

Climate

Aybak features a four-season mediterranean climate (Köppen: Csa/Dsa). The annual mean temperature is 13.4 °C (56.1 °F). Script error: No such module "weather box".

Culture

- Marketplace

The weekly market, an ancient traditional activity of the town is popular and held every Thursday when craftsmen specializing in musical instruments, such as the dutar (two-stringed lute) and the Zirbhagali (a drum made of pottery), exhibit their products for sale. A special marketplace here is known as the Bazar-e-Danbora Faroshi (Lute-Sellers' Bazar or market).

- Cuisine

The town is also famous for its Uzbek bread loaves, which are a popular street side sale.[2]

- Health

The town's hospital serves the entire province.[15]

- Refugees

A refugee camp, Hazrati-Sultan, is located 70 km (43 mi) to the north.[16]

In popular culture

The Northumbrian modernist poet Basil Bunting wrote a poem about the town. "Let them remember Samangan..." stands 32nd in the first book of Odes in his Collected Poems. The poem is dated 1937, hence Bunting cannot have actually visited the town; although he did later travel in the Middle East, whether he ever went to Afghanistan is unknown but unlikely. However, in the same year his first son was born (in Wisconsin) and named Rustam; evidently the legend of Rustam and Sohrab inspired the poem as well as the child's name. The poem itself is an unrhymed sonnet, less experimental than many of Bunting's short poems from the period, but successful in its own elegiac manner.[citation needed][original research?]

References

- ↑ Stephanus of Byzantium, Ethnica, E285.16

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Introducing Samangan (Aibak)". Lonely Planet. http://www.lonelyplanet.com/afghanistan/mazar-e-sharif-and-northeastern-afghanistan/samangan-aibak. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Clammer, Paul (2007). Afghanistan. Lonely Planet. p. 158. ISBN 978-1-74059-642-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=PjhP76JaVgkC&dq=Samangan&pg=PA158. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ↑ Royal Numismatic Society (Great Britain) (1846). The Numismatic chronicle, Volume 8. Royal Numismatic Society.. pp. 107–108. https://books.google.com/books?id=CsqUGHWk9KAC&dq=Samangan&pg=PA108.

- ↑ "Taliban capture sixth provincial capital in northern Afghanistan" (in en). The Guardian. 9 August 2021. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/09/taliban-capture-aibak-sixth-provincial-capital-northern-afghanistan.

- ↑ "Students killed as bomb blast hits Afghan school" (in en-GB). BBC News. 2022-11-30. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-63806005.

- ↑ "Takht-i Rustam monastery, (near) Samangan, Velayat-e Samangan, AF". Mapping of Buddhist Monasteries. http://monastic-asia.wikidot.com/takht-i-rustam. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Takht e Rustam". Afghanistan Cultural Profile. http://www.culturalprofiles.net/afghanistan/Units/303.html. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Samangan Provincial Government". Visiting Arts: Samangan Provincial Department of Information and Culture. http://www.culturalprofiles.org.uk/Afghanistan/Units/pdf/122.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-28.[yes|permanent dead link|dead link}}]

- ↑ "Hazar Sum". Visiting Arts: Samangan Provincial Department of Information and Culture. http://www.culturalprofiles.org.uk/Afghanistan/Units/pdf/299.pdf. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Firdawsi, Firdawsi (1906). The Sháhnáma of Firdausí, Volume 2. K. Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co. Ltd. pp. 118, 122–135. https://books.google.com/books?id=OlIMAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA122. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Curtis, Vesta Sarkhosh (1993). Persian myths. University of Texas Press. p. 41. ISBN 0-292-71158-1. https://archive.org/details/persianmyths00curt. Retrieved 2010-10-15.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 The Geographical journal, Volume 37. Royal Geographical Society (Great Britain). 1911. p. 9. https://books.google.com/books?id=6xsDAAAAMAAJ&q=Horses+of+Samangan. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ↑ "Climate: Samangan - Climate-Data.org". https://en.climate-data.org/asia/afghanistan/samangan/samangan-31391/.

- ↑ Wang Chichhung, ed (2006). Dust in the wind: retracing Dharma Master Xuanzang's Western pilgrimage. Rhythms Monthly. p. 162. ISBN 986-81419-8-2. https://books.google.com/books?id=8rLUbuZLiaIC&pg=PA162.

- ↑ Wang, p. 149

External links

- Dupree, Nancy Hatch (1977): An Historical Guide to Afghanistan. 1st Edition: 1970. 2nd Edition. Revised and Enlarged. Afghan Tourist Organization. [1]

- Satellite map at Maplandia.com

- Pictures from Haibak in 1974

|