Place:Diyarbakır Fortress

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Diyarbakır, Diyarbakır Province, Şanlıurfa Subregion, Southeast Anatolia Region, Turkey |

| Part of | Diyarbakır Fortress and Hevsel Gardens Cultural Landscape |

| Criteria | Cultural: (iv) |

| Reference | 1488 |

| Inscription | 2015 (39th session) |

| Coordinates | Template:Coord/display/title, inline |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 408: Malformed coordinates value. | |

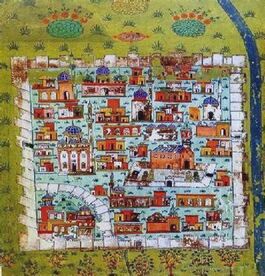

Diyarbakır Fortress, is a historical fortress in Sur, Diyarbakır, Turkey. It consists of an inner fortress and an outer fortress.[1]

The main gates of the fortress are: Dağ (Mountain) Gate, Urfa Gate, Mardin Gate, and Yeni (New) Gate.[1] The walls come from the old Roman city of Amida and were constructed in their present form in the mid-fourth century AD by the emperor Constantius II. According to Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi, the fortifications and powerful walls of Amid-Diyarbakir were built in the middle of 6th century BC under King Tigranes of and during the Yervanduni (Orontid dynasty).They are the widest and longest complete defensive walls in the world after only the Great Wall of China (the Theodosian Walls for example are longer in length, but are not continuous)[2][3]

UNESCO added the building to their tentative list on 2000,[1] and listed it as a World Heritage Site in 2015 along with Hevsel Gardens.

Conservation

From 2000 to 2007, begun during the Mayorship of Feridun Çelik, a major restoration of the Fortress' walls was executed. Buildings that were built directly on the wall were removed, the walls were cleaned and a park was given place alongside the walls.[4] Though the walls and fortress itself were once compared to the Great Wall of China,[5] this started to change as wars broke out during 2015;[6] walls from the fortress collapsed, along with a mosque, two churches, and the homes of many civilians, forcing some sections to be abandoned.[6]

As the war continued, the government of Turkey and UNESCO jointly began a reconstruction and preservation effort, intending to complete it within two years, starting with the demolition of part of the city.[6][7] On July 4, 2015, UNESCO added the fortress and Hevsel Gardens Cultural Landscape to UNESCO's World Heritage List.[8] UNESCO's main focus was to protect the environment of the land itself, more than the heritage of the land. The Turkish Prime Minister also spoke of plans to reconstruct the city walls as a great tourist attraction intended to resemble Paris; this provoked considerable controversy in Diyarbakır, with some locals arguing that they would lose their ancient culture heritage.[6]

Architecture

Diyarbakir fortress is constructed with stone, black basalt, and adobe, and has gone through countless renovations; the basalt fortifications are exceptionally durable, one reason why the structure has remained relatively intact for over 2000 years. Diyarbakir fortress is among the best surviving examples of a castle or fort built with a natural feature like a cliffside or body of water on one side as a boundary. The walls have a symbolic function as well as a defensive purpose, with inscriptions on the inner city's walls (the fort) that testify to the city of Diyarbakir's history.[9]

Today, Diyarbakir Fortress can be divided into two categories, the bailey and the citadel. In the northeast, the citadel contains the first settlement inside Diyarbakir, and those walls stretch 598 meters long. The bailey houses a tower and the city walls, surrounding the much more urban walled city region of Diyarbakir. Most of these walls are constructed with traditional masonry and construction styles; the towers consist of 2-4 floors and are 4.4 meters thick on the ground floor and get thinner on higher floors.[9]

The castle plans reveal the dominance of two different building forms, circular and tetragonal. The walls were divided into five groups, four of which contained the towers around the four main gates, while the fifth contained the citadel towers. It has been found that 65 of the original 82 towers still remain on the outside of the city's walls and 18 of the citadel's towers remain today. Due to cultural differences, the fort has undergone some modifications. The fort was reconstructed, repaired and or heightened over time. However, the overall typology has remained constant in the fort's renovations.[9]

Construction

Diyarbakir fortress was first built in 297 AD by Romans. In 349 AD the walls got significantly expanded under the order of Emperor Constantius II. Over the next 1500+ years, these walls were expanded and fortified using volcanic rock from the surrounding region. There are four main gates and 82 watch towers on the walls.[10] The Diyarbakir city walls have an ancient history dating back to the Romans. The towers at Diyarbakir were mainly built by the Romans and later reconstructed by the Ottomans when they took over the city in the 15th and 16th centuries. During the defeat of the Safavids at Diyarbakir, the Ottomans destroyed the walls with the use of cannons [10] and therefore had to be rebuilt. Today, the walls are largely intact, and form a ring around the old city that is over 3 miles in circumference. The walls are over 33 feet high and are about 10–16 feet thick.[10] In 1930 a part of the wall got demolished.[11] They are the widest and longest complete defensive walls in the world after the Great Wall of China.

History

Diyarbakir Fortress was built, used, and rebuilt during the Roman and Ottoman periods, including the Diyarbakir city walls that measure up to 53 meters long. There are both inner and outer walls; the site also has several gates and towers. Included on the walls are about 63 inscriptions from various historical periods [12] including remains from the Hurrians, Medes, Armenians, Romans, Sassanians, Byzantines, Marwanids, Ayyubids, and Ottomans. The city is considered to have a "multi-cultural, multi-lingual, and multi-culture character".[13] In 2015, the war between the Turkish Army and Kurdish guerillas resulted in damage to the fortress and surrounding monuments, disrupting government plans to conserve the historical fortress in hopes of attracting tourists to the Diyarbakir cultural area.[14] About one-third of the historic Old Town was destroyed by the Turkish government after the clashes ended, irreversibly damaging the ancient city.[15]

See also

- List of World Heritage Sites in Turkey

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Diyarbakır Kalesi ve Surları (Diyarbakır)" .

- ↑ "Diyarbakır Surları" .

- ↑ "Surlar" .

- ↑ Watts, Nicole F. (2011-07-01) (in en). Activists in Office: Kurdish Politics and Protest in Turkey. University of Washington Press. pp. 155. ISBN 9780295800820.

- ↑ "Diyarbakir". http://www.allaboutturkey.com/diyarbakir.htm.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 "Heartbreak in Turkey's Diyarbakır as development transforms ancient Sur". November 21, 2017. https://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2017/11/diyarbakirs-urban-plans-risk-destroying-heritage.html.

- ↑ "Historic Structures damaged in Diyarbakır". October 7, 2015. http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/historic-structures-damaged-in-diyarbakir--89474.

- ↑ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Sites in Denmark, France and Turkey inscribed on UNESCO's World Heritage List" (in en). https://whc.unesco.org/en/news/1315/.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Halifeoglu, Fatma Meral (2013-06-01). "Castle architecture in Anatolia: Fortifications of Diyarbakir" (in en). Frontiers of Architectural Research 2 (2): 209–221. doi:10.1016/j.foar.2013.04.003. ISSN 2095-2635.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 "Diyarbakir City Walls - The Kurdish Project". https://thekurdishproject.org/history-and-culture/kurdish-history/historical-sites-in-kurdistan/diyarbakir-city-walls/.

- ↑ Centre, UNESCO World Heritage. "Diyarbakır Fortress and Hevsel Gardens Cultural Landscape" (in en). https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1488/.

- ↑ "Diyarbakır Fortress and Hevsel Gardens Cultural Landscape (2015) | EBRULI TOURISM- IZMIR-TURKEY" (in en-US). http://www.ebruliturizm.com/4140/diyarbakir-fortress-and-hevsel-gardens-cultural-landscape/.

- ↑ "Diyarbakır Castle and Fortress" (in tr). http://www.kultur.gov.tr/EN,113758/diyarbakir-castle-and-fortress.html.

- ↑ "no return from damage". Rudaw. July 14, 2016. http://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/turkey/140720162.

- ↑ Duvar, Gazete (2017-11-29). "Sur’da neler yaşandı?.." (in tr-TR). https://www.gazeteduvar.com.tr/gundem/2017/11/29/surda-neler-yasandi.

External links

- Sur Tour Guide – Sur Government web site

- Van Berchem, Max, & Josef Strzygowski (1910). Amida: Materiaux pour l'épigraphie et l'histoire Musulmanes du Diyar-Bekr