Place:Tripoli, Libya

Tripoli طرابلس | |

|---|---|

Capital city | |

| Lua error in Module:Multiple_image at line 163: attempt to perform arithmetic on local 'totalwidth' (a nil value). Clockwise from top: Tripoli panorama; Tripoli Central Business District; Arch of Marcus Aurelius; a street in Tripoli; Tripoli Beach Park; Martyrs' Square; and Red Castle Museum | |

OpenStreetMap Location in Libya | |

| Coordinates: [ ⚑ ] : 32°53′14″N 13°11′29″E / 32.88722°N 13.19139°E | |

| Country | Libya |

| Region | Tripolitania |

| District | Tripoli District |

| First settled | 7th century BC |

| Founded by | Phoenicians |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (Tripoli Central) | Ibrahim Khalifi |

| • Governing body | Tripoli Local Council |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1,507 km2 (582 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 81 m (266 ft) |

| Population (2023[1]) | |

| • Total | 1,183,000 [1] |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (EET) |

| Area code(s) | 21 |

| License Plate Code | 5 |

| Website | tlc.gov.ly (archived) |

Tripoli (/ˈtrɪpəli/;[2] Arabic: طرابلس الغرب)[3] is the capital and largest city of Libya, with a population of about 1.183 million people in 2023.[4] It is located in the northwest of Libya on the edge of the desert, on a point of rocky land projecting into the Mediterranean Sea and forming a bay. It includes the port of Tripoli and the country's largest commercial and manufacturing center. It is also the site of the University of Tripoli. The vast Bab al-Azizia barracks, which includes the former family estate of Muammar Gaddafi, is also located in the city. Colonel Gaddafi largely ruled the country from his residence in this barracks.

Tripoli was founded in the 7th century BC by the Phoenicians, who gave it the Libyco-Berber name Oyat (Template:Lang-xpu, Wyʿt),[5][6] before passing into the hands of the Greek rulers of Cyrenaica as Oea (Greek: Ὀία, Oía).[7] Due to the city's long history, there are many sites of archeological significance in Tripoli. Tripoli may also refer to the sha'biyah (top-level administrative division in the Libyan system), the Tripoli District.

Name

In the Arab World, Tripoli is also known as Tripoli-of-the-West (Arabic: طرابلس الغرب Ṭarābulus al-Gharb), to distinguish it from Tripoli, Lebanon, known in Arabic as Ṭarābulus al-Sham (طرابلس الشام), meaning 'Levantine Tripoli'. It is affectionately called "The Mermaid of the Mediterranean" (عروسة البحر ʿArūsat al-Baḥr; lit: 'bride of the sea'), describing its turquoise waters and its whitewashed buildings.

The name derives from Ancient Greek:, literally "three cities", referring to Oea, Sabratha and Leptis Magna. The city of Oea was the only one of the three to survive antiquity, and became known as Tripoli, within a wider region known as Tripolitania. Neighboring Sabratha was sometimes referred to by sailors as "Old Tripoli".

In Arabic, it is called طرابلس, Ṭarābulus (![]() pronunciation (help·info); Libyan Arabic: Ṭrābləs,

pronunciation (help·info); Libyan Arabic: Ṭrābləs, ![]() pronunciation (help·info); Berber: Ṭrables, from Ancient Greek: Trípolis, (

pronunciation (help·info); Berber: Ṭrables, from Ancient Greek: Trípolis, (![]() listen) from Ancient Greek:).

listen) from Ancient Greek:).

History

The city was founded in the 7th century BC by the Phoenicians, who gave it the Libyco-Berber name Oyat (Punic: 𐤅𐤉𐤏𐤕, wyʿt),[5][6] suggesting that the city may have been built upon an existing native Berber city. The Phoenicians were probably attracted to the site by its natural harbor, flanked on the western shore by the small, easily defensible peninsula, on which they established their colony. The city then passed into the hands of the Greek rulers of Cyrenaica as Oea (Greek: Ὀία, Oía). Cyrene was a colony on the North African shore, a bit east of Tambroli and halfway to Egypt. The Carthaginians later wrested it again from the Greeks.

By the later half of the 2nd century BC, it belonged to the Romans, who included it in their province of Africa, and gave it the name of "Regio Syrtica". Around the beginning of the 3rd century AD, it became known as the Regio Tripolitana, meaning "region of the three cities", namely Oea (i.e., modern Tripoli), Sabratha and Leptis Magna. It was probably raised to the rank of a separate province by Septimius Severus, who was a native of Leptis Magna.

In spite of centuries of Roman habitation, the only visible Roman remains, apart from scattered columns and capitals (usually integrated in later buildings), is the Arch of Marcus Aurelius from the 2nd century AD. The fact that Tripoli has been continuously inhabited, unlike e.g., Sabratha and Leptis Magna, has meant that the inhabitants have either quarried material from older buildings (destroying them in the process) or built on top of them, burying them beneath the streets, where they remain largely unexcavated.

There is evidence to suggest that the Tripolitania region was in some economic decline during the 5th and 6th centuries, in part due to the political unrest spreading across the Mediterranean world in the wake of the collapse of the Western Roman empire, as well as pressure from the invading Vandals. It is recorded by Ibn Abd al-Hakam that during the siege of Tripoli by a general of the Rashidun Caliphate named Amr ibn al-As, seven of his soldiers from the clan of Madhlij, sub branch of Kinana, unintentionally found a section on the western side of Tripoli beach that was not walled during their hunting routine.[8] Those seven soldiers then managed to infiltrate through this way without being detected by the city guards, then managed to incite a riot within the city while shouting Takbir, causing the confused Byzantine garrison soldiers to think the Muslim forces were already inside in the city and flee towards their ship leaving Tripoli, thus allowing Amr to subdue the city easily.[8]

According to al-Baladhuri, Tripoli was, unlike Western North Africa, taken by the Muslims very early after Alexandria, in the 22nd year of the Hijra, that is between 30 November 642 and 18 November 643 AD. Following the conquest, Tripoli was ruled by dynasties based in Cairo, Egypt (first the Fatimids, Banu Khazrun and later the Mamluks), and Kairouan in Ifriqiya (the Arab Fihrids, Muhallabids and Aghlabid dynasties). For some time it was a part of the Berber Almohad empire and of the Hafsids kingdom and Banu thabit dynasty.

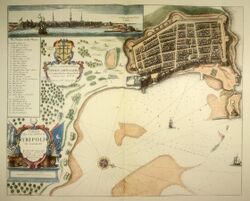

16th to 19th centuries

In 1510, it was taken by Pedro Navarro, Count of Oliveto for Spain, and, in 1530, it was assigned, together with Malta, to the Knights of St. John, who had lately been expelled by the Ottoman Turks from their stronghold on the island of Rhodes.[9] Finding themselves in very hostile territory, the Knights enhanced the city's walls and other defenses. Though built on top of a number of older buildings (possibly including a Roman public bath), much of the earliest defensive structures of the Tripoli castle (or "Assaraya al-Hamra", i.e., the "Red Castle") are attributed to the Knights of St John.

Having previously combated piracy from their base on Rhodes, the reason that the Knights were given charge of the city was to prevent it from relapsing into the nest of Barbary pirates[citation needed] it had been prior to the Spanish occupation. The disruption the pirates caused to the Christian shipping lanes in the Mediterranean had been one of the main incentives for the Spanish conquest of the city.

The knights kept the city with some trouble until 1551, when they were compelled to surrender to the Ottomans, led by the Muslim Turkish commander Turgut Reis.[10] Turgut Reis served as pasha of Tripoli. During his rule, he adorned and built up the city, making it one of the most impressive cities along the North African Coast.[11] Turgut was buried in Tripoli after his death in 1565. His body was taken from Malta, where he had fallen during the Ottoman siege of the island, to a tomb in the Sidi Darghut Mosque which he had established close to his palace in Tripoli. The palace has since disappeared (supposedly it was situated between the so-called "Ottoman prison" and the Arch of Marcus Aurelius), but the mosque, along with his tomb, still stands, close to the Bab Al-Bahr gate.

After the capture by the Ottoman Turks, Tripoli once again became a base of operation for Barbary pirates. One of several Western attempts to dislodge them again was a Royal Navy attack under John Narborough in 1675, of which a vivid eye-witness account has survived.[12]

Effective Ottoman rule during this period (1551–1711) was often hampered by the local Janissary corps. Intended to function as enforcers of local administration, the captain of the Janissaries and his cronies were often the de facto rulers.

In 1711, Ahmed Karamanli, a Janissary officer of Turkish origin, killed the Ottoman governor, the "Pasha", and established himself as ruler of the Tripolitania region. By 1714, he had asserted a sort of semi-independence from the Ottoman Sultan, heralding in the Karamanli dynasty. The Pashas of Tripoli were expected to pay a regular tributary tax to the Sultan but were in all other aspects rulers of an independent kingdom. This order of things continued under the rule of his descendants, accompanied by the brazen piracy and blackmailing until 1835 when the Ottoman Empire took advantage of an internal struggle and re-established its authority.

The Ottoman province (vilayet) of Tripoli (including the dependent sanjak of Cyrenaica) lay along the southern shore of the Mediterranean between Tunisia in the west and Egypt in the east. Besides the city itself, the area included Cyrenaica (the Barca plateau), the chain of oases in the Aujila depression, Fezzan and the oases of Ghadames and Ghat, separated by sandy and stony wastelands. A 16th century Chinese source mentioned Tripoli and described its agricultural and textile products.[13]

Barbary Wars (1801 - 1815)

In the early part of the 19th century, the regency at Tripoli, owing to its piratical practices, was twice involved in war with the United States. In May 1801, the pasha demanded an increase in the tribute ($83,000) which the U.S. government had been paying since 1796 for the protection of their commerce from piracy under the 1796 Treaty with Tripoli. The demand was refused by third President Thomas Jefferson, and a naval force was sent from the United States to blockade Tripoli.

The First Barbary War (1801–1805) dragged on for four years. In 1803, Tripolitan fighters captured the U.S. Navy heavy frigate Philadelphia and took its commander, Captain William Bainbridge, and the entire crew as prisoners. This was after the Philadelphia was run aground when the captain tried to navigate too close to the port of Tripoli. After several hours aground and Tripolitan gun boats firing upon the Philadelphia, though none ever struck the Philadelphia, Captain Bainbridge made the decision to surrender. The Philadelphia was later turned against the Americans and anchored in Tripoli Harbor as a gun battery while her officers and crew were held prisoners in Tripoli. The following year, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Stephen Decatur led a successful daring nighttime raid to retake and burn the warship rather than see it remain in enemy hands. Decatur's men set fire to the Philadelphia and escaped.

A notable incident in the war was the expedition undertaken by diplomatic Consul William Eaton with the objective of replacing the pasha with an elder brother living in exile, who had promised to accede to all the wishes of the United States. Eaton, at the head of a mixed force of US Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, along with Greek, Arab and Turkish mercenaries numbering approximately 500, marched across the Egyptian / Libyan desert from Alexandria, Egypt and with the aid of three American warships, succeeded in capturing Derna. Soon afterward, on 3 June 1805, peace was concluded. The pasha ended his demands and received $60,000 as ransom for the Philadelphia prisoners under the 1805 Treaty with Tripoli.

In 1815, in consequence of further outrages and due to the humiliation of the earlier defeat, Captains Bainbridge and Stephen Decatur, at the head of an American squadron, again visited Tripoli and forced the pasha to comply with the demands of the United States. See Second Barbary War.

Late Ottoman era (1835–1912)

In 1835, the Ottomans took advantage of a local civil war to reassert their direct authority. After that date, Tripoli was under the direct control of the Sublime Porte. Rebellions in 1842 and 1844 were unsuccessful. After the French occupation of Tunisia (1881), the Ottomans increased their garrison in Tripoli considerably.[clarification needed]

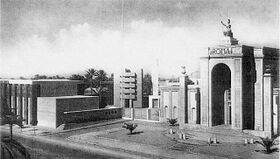

Italian era (1912–1947)

Italy had long claimed that Tripoli fell within its zone of influence and that Italy had the right to preserve order within the state.[14] Under the pretext of protecting its own citizens living in Tripoli from the Ottoman government, it declared war against the Ottomans on 29 September 1911, and announced its intention of annexing Tripoli. On 1 October 1911, a naval battle was fought at Prevesa, Greece, and three Ottoman vessels were destroyed.

By the Treaty of Lausanne, Italian sovereignty over Tripolitania and Cyrenaica was acknowledged by the Ottomans, although the caliph was permitted to exercise religious authority. Italy officially granted autonomy after the war, but gradually occupied the region. Originally administered as part of a single colony, Tripoli and its surrounding province were a separate colony from 26 June 1927 to 3 December 1934, when all Italian possessions in North Africa were merged into one colony.[15] By 1938, Tripoli[16] had 108,240 inhabitants, including 39,096 Italians.[17]

Tripoli underwent a huge architectural and urbanistic improvement under Italian rule:[18] the first thing the Italians did was to create in the early 1920s a sewage system (that until then it lacked) and a modern hospital.

In the coast of the province was built in 1937–1938 a section of the Litoranea Balbia, a road that went from Tripoli and Tunisia's frontier to the border of Egypt. The car tag for the Italian province of Tripoli was "TL".[19]

Furthermore, in 1927, the Italians founded the Tripoli International Fair,with the goal of promoting Tripoli's economy. This is the oldest trade fair in Africa.[20] The so-called Fiera internazionale di Tripoli was one of the main international "Fairs" in the colonial world in the 1930s, and was internationally promoted together with the Tripoli Grand Prix as a showcase of Italian Libya.[21]

The Italians created the Tripoli Grand Prix, an international motor racing event first held in 1925 on a racing circuit outside Tripoli. The Tripoli Grand Prix took place until 1940.[22] The first airport in Libya, the Mellaha Air Base was built by the Italian Air Force in 1923 near the Tripoli racing circuit. The airport is currently called Mitiga International Airport.

Tripoli even had a railway station with some small railway connections to nearby cities, when in August 1941 the Italians started to build a new 1,040-kilometer (646-mile) railway (with a 1,435 mm (4 ft 8.5 in) gauge, like the one used in Egypt and Tunisia) between Tripoli and Benghazi. But the war stopped the construction the next year.

Tripoli was controlled by Italy until 1943 when the provinces of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica were captured by Allied forces. The city fell to troops of the British Eighth Army on 23 January 1943.[23] Tripoli was then governed by the British until independence in 1951. Under the terms of the 1947 peace treaty with the Allies, Italy relinquished all claims to Libya.[24]

Gaddafi era (1969–2011)

Colonel Muammar Gaddafi became leader of Libya on 1 September 1969 after a successful coup d'état.[25]

On 15 April 1986, U.S. President Ronald Reagan ordered major bombing raids, dubbed Operation El Dorado Canyon, against Tripoli and Benghazi, killing 45 Libyan military and government personnel as well as 15 civilians. This strike followed US interception of telex messages from Libya's East Berlin embassy suggesting the involvement of Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi in a bomb explosion on 5 April in West Berlin's La Belle discothèque, a nightclub frequented by US servicemen. Among the alleged fatalities of the 15 April retaliatory attack by the United States was Gaddafi's adopted daughter, Hana Gaddafi.

The United Nations sanctions against Libya imposed in April 1992 under Security Council Resolution 748 were lifted in September 2003, which increased traffic through the Port of Tripoli and through airports in Libya. This lifting of the resolution had a positive impact on the city's economy allowing for more goods to enter the city.

Libyan Civil War (2011)

In February and March 2011, Tripoli witnessed intense anti-government protests and violent government responses resulting in hundreds killed and wounded. The city's Green Square was the scene of some of the protests. The anti-Gaddafi protests were eventually crushed, and Tripoli was the site of pro-Gaddafi rallies.[26]

The city defenses loyal to Gaddafi included the military headquarters at Bab al-Aziziyah (where Gaddafi's main residence was located) and the Mitiga International Airport. At the latter, on 13 March, Ali Atiyya, a colonel of the Libyan Air Force (1951–2011) , defected and joined the revolution.[27]

In late February, rebel forces took control of Zawiya, a city approximately 50 km (31 mi) to the west of Tripoli, thus increasing the threat to pro-Gaddafi forces in the capital. During the subsequent battle of Zawiya, loyalist forces besieged the city and eventually recaptured it by 10 March.[28]

As the 2011 military intervention in Libya commenced on 19 March to enforce a U.N. no-fly zone over the country, the city once again came under air attack. It was the second time that Tripoli was bombed since the 1986 U.S. airstrikes, and the second time since the 1986 airstrike that bombed Bab al-Azizia, Gaddafi's heavily fortified compound.

In July and August, Libyan online revolutionary communities posted tweets and updates on attacks by rebel fighters on pro-government vehicles and checkpoints. In one such attack, Saif al-Islam Gaddafi and Abdullah Senussi were targets.[29] The government, however, denied revolutionary activity inside the capital.

Several months after the initial uprising, rebel forces in the Nafusa Mountains advanced towards the coast, retaking Zawiya and reaching Tripoli on 21 August. On 21 August, the symbolic Green Square, immediately renamed Martyrs' Square by the rebels, was taken under rebel control and pro-Gaddafi posters were torn down and burned.[30]

During a radio address on 1 September, Gaddafi declared that the capital of the Great Socialist People's Libyan Arab Jamahiriya had been moved from Tripoli to Sirte, after rebels had taken control of Tripoli.

In August and September 2014, Islamist armed groups extended their control of central Tripoli. The House of Representatives parliament set up operations on a Greek car ferry in Tobruk. A rival New General National Congress parliament continued to operate in Tripoli.[31][32]

Recent developments

The 2022 Tripoli clashes and 2023 Tripoli clashes continued to disrupt the city.[33]

Law and government

Tripoli and its surrounding suburbs all lie within the Tripoli sha'biyah (district). In accordance with Libya's former Jamahiriya political system, Tripoli comprises Local People's Congresses where, in theory, the city's population discuss different matters and elect their own people's committee; at present[when?] there are 29 Local People's Congresses. In reality, the former revolutionary committees severely limited the democratic process by closely supervising committee and congress elections at the branch and district levels of governments, Tripoli being no exception.

Tripoli is sometimes referred to as "the de jure capital of Libya" because none of the country's ministries are actually located in the capital. Even the former National General People's Congress was held annually in the city of Sirte rather than in Tripoli. As part of a radical decentralization program undertaken by Gaddafi in September 1988, all General People's Committee secretariats (ministries), except those responsible for foreign liaison (foreign policy and international relations) and information, were moved outside Tripoli. According to diplomatic sources, the former Secretariat for Economy and Trade was moved to Benghazi; the Secretariat for Health to Kufra; and the remainder, excepting one, to Sirte, Muammar Gaddafi's birthplace. In early 1993 it was announced that the Secretariat for Foreign Liaison and International Co-operation was to be moved to Ra's Lanuf. In October 2011, Libya fell to The National Transitional Council (N.T.C.), which took full control, abolishing the Gaddafi-era system of national and local government.

Geography

Tripoli lies at the western extremity of Libya close to the Tunisian border, on the continent of Africa. Over a thousand kilometers (621 miles) separates Tripoli from Libya's second largest city, Benghazi. Coastal oases alternate with sandy areas and lagoons along the shores of Tripolitania for more than 300 km (190 mi). The city lies about 70 kilometers north from the Nafusa Mountains, the source of seasonal rivers like Wadi Al-Mjeneen.

Administrative division

Until 2007, the "Sha'biyah" included the city, its suburbs and their immediate surroundings. In older administrative systems and throughout history, there existed a province ("muhafazah"), state ("wilayah") or city-state with a much larger area (though not constant boundaries), which is sometimes mistakenly referred to as Tripoli but more appropriately should be called Tripolitania.

As a District, Tripoli borders the following districts:

- Murqub – east

- Jabal al Gharbi – south

- Jafara – southwest

- Zawiya – west

Climate

Tripoli has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen: BSh)[34] with hot and dry, prolonged summers and relatively wet mild winters. Although virtually rainless, summers are hot and muggy with temperatures that often exceed 38 °C (100 °F); average July temperatures are between 22 and 33 °C (72 and 91 °F). In December, temperatures have reached as low as 0 °C (32 °F), but the average remains at between 9 and 18 °C (48 and 64 °F). The average annual rainfall is less than 400 millimeters (16 inches). Snowfall has occurred in past years.[35]

The rainfall can be very erratic. Epic floods in 1945 left Tripoli underwater for several days, but two years later an unprecedented drought caused the loss of thousands of head of cattle. Deficiency in rainfall is no doubt reflected in an absence of permanent rivers or streams in the city as is indeed true throughout the entire country. The allocation of limited water is considered of sufficient importance to warrant the existence of the Secretariat of Dams and Water Resources, and damaging a source of water can be penalized by a heavy fine or imprisonment.[36]

The Great Manmade River, a network of pipelines that transport water from the desert to the coastal cities, supplies Tripoli with its water.[37] The grand scheme was initiated by Gaddafi in 1982.[citation needed]

Martyrs' Square, located near the waterfront is scattered with palm trees, the most abundant plant used for landscaping in the city. The Tripoli Zoo, located south of the city center, is a large reserve of plants, trees and open green spaces and was the country's biggest zoo.[citation needed] The zoo was forced to shut for safety reasons due to the Libyan Civil War, with many animals becoming more and more traumatised and distressed. After the overthrow of Muammar Gaddafi, the BBC published a short news film detailing the problems the zoo now faced, from a lack of money to feed the animals, to a fragile security system. The animals, the BBC said, were recovering slowly and returning to normal.[38]

Script error: No such module "weather box".

Climate change

A 2019 paper published in PLOS One estimated that under Representative Concentration Pathway 4.5, a "moderate" scenario of climate change where global warming reaches ~2.5–3 °C (4.5–5.4 °F) by 2100, the climate of Tripoli in the year 2050 would most closely resemble the current climate of Taiz. The annual temperature would increase by 1.9 °C (3.4 °F), and the temperature of the warmest month by 3.1 °C (5.6 °F), while the temperature of the coldest month would increase by 0.3 °C (0.54 °F).[41][42] According to Climate Action Tracker, the current warming trajectory appears consistent with 2.7 °C (4.9 °F), which closely matches RCP 4.5.[43]

Economy

Tripoli is one of the main hubs of Libya's economy along with Misrata. It is the leading center of banking, finance and communication in the country and is one of the leading commercial and manufacturing cities in Libya. Many of the country's largest corporations locate their headquarters and home offices in Tripoli as well as the majority of international companies.[citation needed]

Major manufactured goods include processed food, textiles, construction materials, clothing and tobacco products. Since the lifting of sanctions against Libya in 1999 and again in 2003, Tripoli has seen a rise in foreign investment as well as an increase in tourism. Increased traffic has also been recorded in the city's port as well as Libya's main international airport, Tripoli International.[citation needed]

The city is home to the Tripoli International Fair, an international industrial, agricultural and commercial event located on Omar Muktar Avenue. One of the active members of the Global Association of the Exhibition Industry (UFI), located in the French capital Paris, the international fair is organized annually and takes place from 2–12 April. Participation averages around 30 countries as well as more than 2000 companies and organizations.[citation needed]

Since the rise in tourism and influx of foreign visitors, there has been an increased demand for hotels in the city. To cater for these increased demands, the Corinthia Bab Africa Hotel located in the central business district was constructed in 2003 and is the largest hotel in Libya. Other high end hotels in Tripoli include the Al Waddan Intercontinental and the Tripoli Radisson Blu Hotel as well as others.[44]

There is a project under construction which will finish by 2015. It is a part of the Tripoli business center and it will have towers and hotels, a marketing center, restaurants and above ground and underground parking. The cost is planned to be more than 3.0 billion Libyan dinars (US$2.8 billion)

Companies with head offices in Tripoli include Afriqiyah Airways and Libyan Airlines.[45][46] Buraq Air has its head office on the grounds of Mitiga International Airport.[47]

By 2017, due to the effects of the Libyan Civil War (2011), rising inflation, militia infighting, bureaucratic issues, multiple central banks, fragmented governments, corruption, and other issues, the economic state of Libya is suffering. Locals in Libya must purchase dollars on the black market, rather than receiving dollars on the official rate of 1.37 Dinars to 1 US Dollar, due to Central bank(s) refusal to give US dollars to the public, the pricing of Dollars amounts to 10 Dinars to 1 US dollar on the black market, driving the local Libyan economy into ruin and undermining local peoples purchasing power. Militias however have been benefiting from this exploit due to their armed influences and corrupt natures by purchasing dollars on the official rate of 1.30 to 1, and selling them US$1 to 10 LYD.

Architecture

The city's old town, the Medina, mostly took on its current form and appearance during the Ottoman period (16th century and after) and in particular during the period of Karamanli rule.[48][49](p383) Many ancient Roman columns can be found re-used in various historical buildings in the city.[50]

The city walls were rebuilt and modified many times from the Roman period up to the Ottoman period.[51] Their final form, which determined the overall pentagonal layout of the Medina today, dates from 16th century, when the Ottomans refortified the town.[49](p389) The city historically had at least three gates: Bab Hawwara to the southeast (probably Bab al-Mensha today), Bab Zenata (originally Bab al-Ashdar) to the west, and Bab al-Bahr to the north (close to the sea).[49](pp386-387)[52] Following later demolitions, what remains of the walls today are a section along the southwest flank of the Medina and another section to the southeast.[52]

The oldest Islamic monument in Tripoli is the al-Naqah Mosque, probably first built by the Fatimid caliph al-Mu'izz in 973 but possibly even older.[53] It was renovated or rebuilt in the early 17th century.[50][54] Most other mosques in the city date in their current form to the Ottoman era.[53] They generally have a hypostyle form with columns supporting multiple domes.[52] The largest ones include the Mosque of Darghut Pasha (completed in 1556) and the Mosque of Ahmad Pasha al-Karamanli (completed c. 1738). In addition to the main prayer space, both of these mosques are accompanied by a complex of other buildings such as madrasas, bathhouses, markets (suqs), and the mausoleums of their eponymous founders. Other notable mosques in the city include the Mosque of Sidi Salem (built in the late 15th century and restored in 1670), the Mosque of Mahmud Khaznadar (1680), the Mosque of Shai'b al-Ain (1699), and the Gurgi Mosque (1834).[52][49]

The earliest recorded madrasa in the city was the al-Mustansiriyya Madrasa built between 1257 and 1260, but it has not survived.[52] Today, the Madrasa of Uthman Pasha (1654) is one of the most notable preserved examples of this type of building. Its main component is a square courtyard surrounded by vaulted galleries and small rooms where students lived. Attached to the northeast corner of the building are a two square domed chambers, with the smaller one serving as a mosque and the larger one housing the tombs of Uthman Pasha and others.[52]

Of the many hammams (bathhouses) that once existed in the city, only three notable examples remain today: the Hammam al-Kabir ("Great Bath"), of which only a large domed chamber survives, the Hammam al-Hilqa, which was still in use in the late 20th century, and the Hammam of Darghut Pasha, built in the 17th century next to the mosque of the same name.[52]

The Medina also preserves urban caravanserais (funduq in Arabic, plural: fanadiq) from the Ottoman period. These generally consist of a two-storey building centered around a courtyard. The first floor was usually used for storage while the second floor was for shops.[52] The historic houses in the city also have a similar form, with multiple stories and an internal courtyard. They are roofed with vaults or flat wooden roofs. Their decoration can consist of carved stucco and tilework.[52]

A clock tower, 18 meters tall, was built in 1866–70 by the Ottoman governor and is still one of the city's landmarks.[56][57]

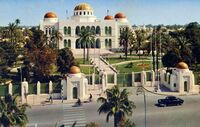

Under Italian occupation, various buildings were constructed in an Italianate style.[50] The Tripoli Cathedral (now a mosque) was also built in this period.[58] There are a number of buildings that were constructed by the Italian colonial rulers and later demolished under Gaddafi. They included the Royal Miramare Theatre, next to the Red Castle, and Tripoli Railway Central Station.[citation needed]

Culture

The Red Castle of Tripoli (Assaraya al-Hamra), a vast palace complex with numerous courtyards, dominates the city skyline and is located on the outskirts of the Medina. There are some classical statues and fountains from the Ottoman period scattered around the castle. It houses the Red Castle Museum.

Places of worship

Among the places of worship, there are predominantly Muslim mosques.[59] There are also Christian churches and temples: Apostolic Vicariate of Tripoli (Catholic Church), Coptic Orthodox Church, Protestant churches, Evangelical Churches.

Education

The largest university in Tripoli, the University of Tripoli, is a public university providing free education to the city's inhabitants. Private universities and colleges have also begun to crop up in the last few years.

International schools:

- Trafalgar International School Tripoli

- Lycée Français de Tripoli

- Deutsche Schule Tripolis

- Scuola Italiana Al Maziri

- Russian Embassy School in Tripoli

- British School Tripoli

- American School of Tripoli

- ISM International School

- Ladybird International School

- Tripoli International School

- Tripoli World Academy

- Global Knowledge School

- مدرسة المعرفة الدولية السراج

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in the Libyan capital. Tripoli is home of the most prominent football clubs in Libya including Al Madina, Al Ahly Tripoli and Al-Ittihad Tripoli. Other sports clubs based in Tripoli include Al Wahda Tripoli and Addahra.

The city also played host to the Italian Super Cup in 2002. The 2017 Africa Cup of Nations were to be played in Libya, three of the venues were supposed to be in Tripoli, but it was cancelled due to the ongoing conflict of the Second Libyan Civil War.

Tripoli hosted the final games of the official 2009 African Basketball Championship.

Transport

Tripoli International Airport was the largest airport in Tripoli and Libya before being destroyed during the second Libyan civil war in 2014. Tripoli has since been served by a smaller local airport Mitiga International Airport, which is currently the largest airport in Libya.

Tripoli is the interim destination of a railway from Sirte under construction in 2007.[60]

In July 2014 The Tripoli international Airport was destroyed, following the Battle of Tripoli Airport, when Zintani militias in charge of security were attacked by Islamist militias of the GNC, code naming the operation 'Libya Dawn' also known as "Libya Dawn Militias", led by Misurati militia general Salah Badi. The event happened after secular Zintani militias were accused with claims of smuggling drugs, alcohol and illegal items, known to have past ties with the Gaddafi Regime. Libya's Mufti Sadiq al Ghariani has praised the Libya Dawn Operation.

The result of the Battle for Tripoli's central airport was its complete destruction with 90% of the facilities incapacitated, or burned down with an unknown estimate Billions of dollars in Damage, with another 10 or so planes destroyed. The airport was shelled with Grad rockets with reports of the Air Traffic Control tower completely destroyed, including the main reception building completely wrecked. Surrounding civilian residential areas and infrastructure, of which include Bridges, Electricity equipment, water equipment, and roads were also damaged in the fighting. Oil storage tankers containing large reserves of Kerosene fuels, gases and related chemicals were burnt and large plumes of smoke rose into the air.

Reconstruction efforts are underway with the GNA giving a contract amounting to $78 million to an Italian firm 'Emaco Group' or "Aeneas Consorzio", to rebuild the destroyed facilities. All flights have been diverted to ex-military base known as Mitiga International Airport as of 2017.

Gallery

The An-Naga mosque is a 1610 reconstruction of a 10th-century mosque, it has original richly decorated Roman capitals crowning the forest of columns in its multi-domed hall.[61]

International relations

Sister cities:

- Baltimore, United States

- Belgrade, Serbia

- Belo Horizonte, Brazil (2003)

- Madrid, Spain

- Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina (1976)

See also

- European enclaves in North Africa before 1830

- Libyan Civil War

- Barbary treaties

- Gran Premio di Tripoli

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Libya". 6 November 2023. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/libya/.

- ↑ Jones, Daniel (2003), Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter, eds., English Pronouncing Dictionary, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 3-12-539683-2

- ↑ "Tripoli - History, Geography, & Facts". 2020-03-26. https://www.britannica.com/place/Tripoli., Van Donzel, E.J. (1994). Islamic Desk Reference. E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-09738-4. https://books.google.com/books?id=zHxsWspxGIIC&pg=PA456. Retrieved 2022-09-30., Great Britain. Admiralty (1920). A Handbook of Libya. I.D. 1162. H.M. Stationery Office. p. 134. https://books.google.com/books?id=wYhDAQAAMAAJ.

- ↑ "Major Urban Areas – Population". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. https://www.cia.gov/the-world-factbook/countries/libya/.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Anthony R. Birley (2002). Septimus Severus. Routledge. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-13470746-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=GcmEAgAAQBAJ&pg=PA2.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Mansour Ghaki (2015), "Toponymie et Onomastique Libyques: L'Apport de l'Écriture Punique/Néopunique", in Anna Maria di Tolla (in fr), La Lingua nella Vita e la Vita della Lingua: Itinerari e Percorsi degli Studi Berberi, Studi Africanistici: Quaderni di Studi Berberi e Libico-Berberi, No. 4, Naples: Unior, pp. 65–71, ISBN 978-88-6719-125-3, https://www.academia.edu/29670337

- ↑ Daniel J. Hopkins (1997). Merriam-Webster's Geographical Dictionary (Index). Merriam-Webster. ISBN 0-87779-546-0. https://archive.org/details/merriamwebstersg1998merr.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Khalid, Mahmud (2020). "Libya in the shadows of Islam.. How did Amr ibn al-Aas and his companions conquer Cyrenaica and Tripoli?" (in ar). p. Ibn Abd al-Hakam: al-Maqrib, pp. 198, 199. https://www.aljazeera.net/midan/intellect/history/2020/10/5/%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A8%D9%8A%D8%A7-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B8%D9%90%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%84-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A5%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85-%D9%83%D9%8A%D9%81-%D9%81%D8%AA%D8%AD-%D8%B9%D9%85%D8%B1%D9%88-%D8%A8%D9%86. "Ibn Abd al-Hakam: al-Maqrib, pp. 198, 199"

- ↑ Britannica, Tripoli, britannica.com, USA, accessed on 7 July 2019

- ↑ Reynolds, Clark G. (1974). Command of the Sea – The History and Strategy of Maritime Empires. Morrow. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-688-00267-1. "Ottomans extended their western maritime frontier across North Africa under the naval command of another Greek Moslem, Torghoud (or Dragut), who succeeded Barbarossa upon the latter's death in 1546."

- ↑ Braudel, Fernand (1995). The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II, Volume 2. University of California Press. pp. 908–909. ISBN 978-0-520-20330-3. https://archive.org/details/mediterraneanthe01brau/page/908. "Of all the corsairs who preyed on Sicilian wheat, Dragut (Turghut) was the most dangerous. A Greek by birth, he was now about fifty years old and behind him lay a long and adventurous career including four years in the Genoese galleys."

- ↑ The Diary of Henry Teonge Chaplain on Board HM's Ships Assistance, Bristol and Royal Oak 1675–1679. The Broadway Travellers. Edited by Sir E. Denison Ross and Eileen Power. London: Routledge, [1927] 2005. ISBN:978-0-415-34477-7.

- ↑ Chen, Yuan Julian (2021-10-11). "Between the Islamic and Chinese Universal Empires: The Ottoman Empire, Ming Dynasty, and Global Age of Explorations". Journal of Early Modern History 25 (5): 422–456. doi:10.1163/15700658-bja10030. ISSN 1385-3783. https://www.academia.edu/59068575.

- ↑ Charles Wellington Furlong (December 1911). "The Taking of Tripoli: What Italy Is Acquiring". The World's Work: A History of Our Time XXIII: 165–176. https://books.google.com/books?id=Vv--PfedzLAC&pg=PA165. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- ↑ "Dadfeatured: ITALIAN TRIPOLI". 17 October 2018. https://dadfeatured.blogspot.com/2018/10/was-capital-of-italian-libya.html.

- ↑ "Map of Italian Tripoli in 1930". http://www.ernandes.net/ricordi/rionelido/cap01/tripolimap30.jpg.

- ↑ The Statesman's Yearbook 1948. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 1040.

- ↑ McLaren, Brian (29 January 2017). Architecture and Tourism in Italian Colonial Libya: An Ambivalent Modernism. University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295985428. https://books.google.com/books?id=_lrYlxdX7DIC&pg=PA17.

- ↑ Berionne, Michele. "Benvenuto in Targhe a Roma" (in it). targheitaliane.it. http://www.targheitaliane.it/index_i.html?/italy/colonie/libia_i.html.

- ↑ "Tif History". gbf.com.ly. 2008. http://www.gbf.com.ly/tif37/english/tifhistory.php.

- ↑ "MUSULMANI – 1937 – L'ITALIA IN MEDIO ORIENTE". http://cronologia.leonardo.it/storia/a1937f.htm.

- ↑ Video of Tripoli Grand Prix on YouTube

- ↑ "Tunisia and Kasserine Pass". http://olive-drab.com/od_history_ww2_ops_battles_1943tunisia.php.

- ↑ Hagos, Tecola W. (20 November 2004). "Treaty Of Peace With Italy (1947), Evaluation And Conclusion" . Ethiopia Tecola Hagos. Retrieved 18 July 2006.

- ↑ "Tripoli architect remembers its glorious days". Indianexpress.com. 2 September 2011. https://indianexpress.com/article/cities/delhi/tripoli-architect-remembers-its-glorious-days/.

- ↑ "Pro-Gaddafi demonstrations in Tripoli – Libya February 17th – Archive site". http://archive.libyafeb17.com/2011/02/pro-gaddafi-demonstrations-in-tripoli/.

- ↑ "Breaking: Body of Al Jazeera Cameraman Ali Al Jabir Arrives in Doha". Libyafeb17.com. 13 March 2011. http://archive.libyafeb17.com/2011/03/crowd-mourns-ali-hassan-al-jabir/.

- ↑ Neely, Bill (10 March 2011). "Zawiya town centre devastated and almost deserted | Libya". London. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2011/mar/10/zawiya-town-itv-regime-battle.

- ↑ Worth, Robert F.. "Gaddafi's son Saif al-Islam comes out of hiding – and wants to be president" (in en). The Times. ISSN 0140-0460. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/gaddafis-son-saif-al-islam-comes-out-of-hiding-and-wants-to-be-president-hsjnkjdzn.

- ↑ "Libyan rebels take Tripoli's Green Square" (in en). National Post. Agence France-Presse. 2011-08-22. https://nationalpost.com/news/libyan-rebels-take-tripolis-green-square.

- ↑ "Libya's Islamist militias claim control of capital". The Washington Post. Associated Press. 24 August 2014. https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/middle_east/egypt-denies-intervening-in-libya/2014/08/24/88b364ee-2b7d-11e4-be9e-60cc44c01e7f_story.html.

- ↑ Chris Stephen (9 September 2014). "Libyan parliament takes refuge in Greek car ferry". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/sep/09/libyan-parliament-refuge-greek-car-ferry.

- ↑ "Why did clashes break out in Libya's Tripoli?" (in en). https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2023/8/17/why-did-clashes-break-out-in-libyas-tripoli.

- ↑ Kottek, M.; Grieser, J.; Beck, C.; Rudolf, B.; Rubel, F. (April 2006). "World Map of Köppen-Geiger Climate Classification, updated". Meteorol. Z.. pp. 259–263. http://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at/pdf/kottek_et_al_2006_A4.pdf.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 "World Weather Information Service – Tripoli". World Meteorological Organization. May 2011. http://worldweather.wmo.int/157/c01179.htm.

- ↑ Harold D. Nelson, ed (1979). Libya a country study (Area handbook series): Foreign Area Studies. The American University, Washington, D.C.. p. 66.

- ↑ Watkins, John (18 March 2006). "Libya's Thirst for 'Fossil Water'". BBC News. http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/sci/tech/4814988.stm#map.

- ↑ "Bleak future for Tripoli zoo animals?" (in en-GB). BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/world-africa-16371108.

- ↑ "Klimatafel von Tripolis (Flugh.) / Libyen" (in de). Baseline climate means (1961–1990) from stations all over the world. Deutscher Wetterdienst. http://www.dwd.de/DWD/klima/beratung/ak/ak_620100_kt.pdf.

- ↑ "Appendix I: Meteorological Data". Springer. http://extras.springer.com/2007/978-1-4020-4577-6/Book_Shahin_ISBN_9781402045776_Appendix.pdf.

- ↑ Bastin, Jean-Francois; Clark, Emily; Elliott, Thomas; Hart, Simon; van den Hoogen, Johan; Hordijk, Iris; Ma, Haozhi; Majumder, Sabiha et al. (10 July 2019). "Understanding climate change from a global analysis of city analogues". PLOS ONE 14 (7): S2 Table. Summary statistics of the global analysis of city analogues.. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0217592. PMID 31291249. Bibcode: 2019PLoSO..1417592B.

- ↑ "Cities of the future: visualizing climate change to inspire action". Current vs. future cities. https://crowtherlab.pageflow.io/cities-of-the-future-visualizing-climate-change-to-inspire-action.

- ↑ "The CAT Thermometer". https://climateactiontracker.org/global/cat-thermometer/.

- ↑ Libya Opportunities for British goods and services exporters. Retrieved 18 February 2010

- ↑ "Contact Us ." Afriqiyah Airways. Retrieved on 9 November 2009.

- ↑ "Libyan Airlines." Arab Air Carriers Organization. Retrieved on 9 November 2009.

- ↑ "Company Profile ." Buraq Air. Retrieved on 14 May 2010.

- ↑ Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Tripoli (Libiya)" (in en). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. pp. 286. ISBN 9781134613663. https://www.archnet.org/collections/126.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 49.2 49.3 Micara, Ludovico (2008). "The Ottoman Tripoli: A Mediterranean Medina". in Jayyusi, Salma Khadra (in en). The City in the Islamic World. 1. Brill. pp. 383–406. ISBN 978-90-474-4265-3. https://books.google.com/books?id=tO55DwAAQBAJ&dq=naqah+mosque+tripoli&pg=PA390.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 Bloom, Jonathan M., ed (2009). "Tripoli (ii)" (in en). The Grove Encyclopedia of Islamic Art and Architecture. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195309911. https://books.google.com/books?id=un4WcfEASZwC.

- ↑ Warfelli, Muhammad (1976). "The Old City of Tripoli" (in en). Some Islamic Sites in Libya: Tripoli, Ajdabiyah and Ujlah. Art and Archeology Research Papers. Department of Antiquities, Tripoli. pp. 5–7.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 52.4 52.5 52.6 52.7 52.8 Warfelli, Muhammad (1976). "The Old City of Tripoli" (in en). Some Islamic Sites in Libya: Tripoli, Ajdabiyah and Ujlah. Art and Archeology Research Papers. Department of Antiquities, Tripoli. pp. 5–7.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Petersen, Andrew (1996). "Libiya (Libyan Arab People's Socialist State)" (in en). Dictionary of Islamic Architecture. Routledge. pp. 165–166. ISBN 9781134613663. https://www.archnet.org/collections/126.

- ↑ Bloom, Jonathan M. (2020) (in en). Architecture of the Islamic West: North Africa and the Iberian Peninsula, 700-1800. Yale University Press. pp. 218–219. ISBN 9780300218701. https://books.google.com/books?id=IRHbDwAAQBAJ.

- ↑ Karamanly (Qaramanli) House Museum, https://www.temehu.com/Cities_sites/museum-of-karamanli-house.htm

- ↑ "Libya on edge as oil tensions rise" (in en). 18 March 2014. https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2014/3/18/libya-on-edge-as-oil-tensions-rise.

- ↑ "Tripoli Clock Tower" (in en). 27 August 2018. https://libyaobserver.ly/videos/tripoli-clock-tower.

- ↑ McLaren, Brian (2006) (in en). Architecture and Tourism in Italian Colonial Libya: An Ambivalent Modernism. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-98542-8. https://books.google.com/books?id=_lrYlxdX7DIC.

- ↑ Britannica, Libya, britannica.com, USA, accessed on 7 July 2019

- ↑ Briginshaw, David (1 January 2001). "Libya's First Two Railway Lines Start To Take Shape". International Railway Journal. Retrieved 30 December 2007.

- ↑ Fiona Dunlop (29 October 2010), A long weekend in… Tripoli, https://howtospendit.ft.com/travel/2879-a-long-weekend-in-tripoli

- Includes text from Collier's New Encyclopedia (1921).

Further reading

- London, Joshua E. (2005). Victory in Tripoli – How America's War with the Barbary Pirates Established the U.S. Navy and Shaped a Nation New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Nora Lafi (2002). Une ville du Maghreb entre Ancien Régime et réformes ottomanes. Genèse des institutions municipales à Tripoli de Barbarie (1795–1911). Paris: L'Harmattan. 305 p. Amamzon.fr.

- Miss Tully (1816) Letters written during a ten-year's residence at the Court of Tripoli, 1783–1795, with a new Introduction by Caroline Stone. (Hardinge Simpole, 2008). Hardinge Simpole – Travellers in the Wider Levant Series.

- Journal of Libyan Studies 3, 1 (2002) p. 59–68: "Local Elites and Italian Town Planning Procedures in Early Colonial Tripoli (1911–1912)" by Denis Bocquet and Nora Lafi http://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/docs/00/12/82/40/PDF/lafi-bocquet_local_elites.pdf

External links

|