Protocol stack

The protocol stack or network stack is an implementation of a computer networking protocol suite or protocol family. Some of these terms are used interchangeably but strictly speaking, the suite is the definition of the communication protocols, and the stack is the software implementation of them.[1]

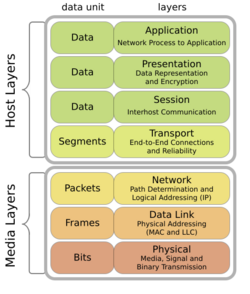

Individual protocols within a suite are often designed with a single purpose in mind. This modularization simplifies design and evaluation. Because each protocol module usually communicates with two others, they are commonly imagined as layers in a stack of protocols. The lowest protocol always deals with low-level interaction with the communications hardware. Each higher layer adds additional capabilities. User applications usually deal only with the topmost layers.[2]

General protocol suite description

T ~ ~ ~ T [A] [B]_____[C]

Imagine three computers: A, B, and C. A and B both have radio equipment and can communicate via the airwaves using a suitable network protocol (such as IEEE 802.11). B and C are connected via a cable, using it to exchange data (again, with the help of a protocol, for example Point-to-Point Protocol). However, neither of these two protocols will be able to transport information from A to C, because these computers are conceptually on different networks. An inter-network protocol is required to connect them.

One could combine the two protocols to form a powerful third, mastering both cable and wireless transmission, but a different super-protocol would be needed for each possible combination of protocols. It is easier to leave the base protocols alone, and design a protocol that can work on top of any of them (the Internet Protocol is an example). This will make two stacks of two protocols each. The inter-network protocol will communicate with each of the base protocol in their simpler language; the base protocols will not talk directly to each other.

A request on computer A to send a chunk of data to C is taken by the upper protocol, which (through whatever means) knows that C is reachable through B. It, therefore, instructs the wireless protocol to transmit the data packet to B. On this computer, the lower layer handlers will pass the packet up to the inter-network protocol, which, on recognizing that B is not the final destination, will again invoke lower-level functions. This time, the cable protocol is used to send the data to C. There, the received packet is again passed to the upper protocol, which (with C being the destination) will pass it on to a higher protocol or application on C.

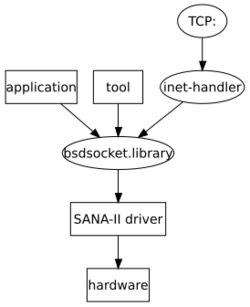

In practical implementation, protocol stacks are often divided into three major sections: media, transport, and applications. A particular operating system or platform will often have two well-defined software interfaces: one between the media and transport layers, and one between the transport layers and applications. The media-to-transport interface defines how transport protocol software makes use of particular media and hardware types and is associated with a device driver. For example, this interface level would define how TCP/IP transport software would talk to the network interface controller. Examples of these interfaces include ODI and NDIS in the Microsoft Windows and DOS environment. The application-to-transport interface defines how application programs make use of the transport layers. For example, this interface level would define how a web browser program would talk to TCP/IP transport software. Examples of these interfaces include Berkeley sockets and System V STREAMS in Unix-like environments, and Winsock for Microsoft Windows.

Examples

| Protocol | Layer |

|---|---|

| HTTP | Application |

| TCP | Transport |

| IP | Internet or network |

| Ethernet | Link or data link |

| IEEE 802.3ab | Physical |

Spanning layer

An important feature of many communities of interoperability based on a common protocol stack is a spanning layer, a term coined by David Clark[3]

Certain protocols are designed with the specific purpose of bridging differences at the lower layers, so that common agreements are not required there. Instead, the layer provides the definitions that permit translation to occur between a range of services or technologies used below. Thus, in somewhat abstract terms, at and above such a layer common standards contribute to interoperation, while below the layer translation is used. Such a layer is called a spanning layer in this paper. As a practical matter, real interoperation is achieved by the definition and use of effective spanning layers. But there are many different ways that a spanning layer can be crafted.

In the Internet protocol stack, the Internet Protocol Suite constitutes a spanning layer that defines a best-effort service for global routing of datagrams at Layer 3. The Internet is the community of interoperation based on this spanning layer.

See also

- Cross-layer optimization

- DECnet

- Hierarchical internetworking model

- Protocol Wars

- Recursive Internetwork Architecture

- Service layer

- Signalling System No. 7

- Systems Network Architecture

- Wireless Application Protocol

- X.25

References

- ↑ "What is a protocol stack?". WEBOPEDIA. 24 September 1997. http://www.webopedia.com/TERM/P/protocol_stack.html. "A [protocol stack is a] set of network protocol layers that work together. The OSI Reference Model that defines seven protocol layers is often called a stack, as is the set of TCP/IP protocols that define communication over the Internet."

- ↑ Georg N. Strauß (2010-01-09). "The OSI Model, Part 10. The Application Layer". Ika-Reutte. http://www.ika-reutte.at/elearning/OSI_Model.doc. "The Application layer is the topmost layer of the OSI model, and it provides services that directly support user applications, such as database access, e-mail, and file transfers."

- ↑ David Clark (1997). Interoperation, Open Interfaces, and Protocol Architecture. National Research Council. ISBN 9780309060363.

|