Religion:Chinese gods and immortals

Chinese gods and immortals are beings in various Chinese religions seen in a variety of ways and mythological contexts.

Many are worshiped as deities because traditional Chinese religion is polytheistic, stemming from a pantheistic view that divinity is inherent in the world.[1]

The gods are energies or principles revealing, imitating, and propagating the way of heaven (天, Tian),[2] which is the supreme godhead manifesting in the northern culmen of the starry vault of the skies and its order.[citation needed] Many gods are ancestors or men who became deities for their heavenly achievements. Most gods are also identified with stars and constellations.[3] Ancestors are regarded as the equivalent of Heaven within human society,[4] and therefore, as the means of connecting back to Heaven, which is the "utmost ancestral father" (曾祖父, zēngzǔfù).[5]

There are a variety of immortals in Chinese thought, and one major type is the xian, which is thought in some religious Taoism movements to be a human given long or infinite life. Gods are innumerable, as every phenomenon has or is one or more gods, and they are organised in a complex celestial hierarchy.[6] Besides the traditional worship of these entities, Confucianism, Taoism, and formal thinkers in general give theological interpretations affirming a monistic essence of divinity.[7]

Overview

"Polytheism" and "monotheism" are categories derived from Western religion and do not fit Chinese religion, which has never conceived the two things as opposites.[8] Tian bridges the gap between supernatural phenomena and many kinds of beings, giving them a single source from spiritual energy in some Chinese belief systems.[2] However, there is a significant belief in Taoism which differentiates tian from the forces of earth and water, which are held to be equally powerful.[9]

Since all gods are considered manifestations of qì (氣), the "power" or pneuma of Heaven, in some views of tian, some scholars have employed the term "polypneumatism" or "(poly)pneumatolatry", first coined by Walter Medhurst (1796–1857), to describe the practice of Chinese polytheism.[10] Some Taoists consider deities the manifestation of the Tao.[citation needed]

In the theology of the classic texts and Confucianism, "Heaven is the lord of the hundreds of deities".[11]

Modern Confucian theology sometimes compares them to substantial forms or entelechies (inner purposes) as described by Leibniz as a force that generates all types of beings, so that "even mountains and rivers are worshipped as something capable of enjoying sacrificial offerings".[12]

Unlike in Hinduism, the deification of historical persons and ancestors is not traditionally the duty of Confucians or Taoists.[clarification needed] Rather, it depends on the choices of common people; persons are deified when they have made extraordinary deeds and have left an efficacious legacy. Yet, Confucians and Taoists traditionally may demand that state honours be granted to a particular deity. Each deity has a cult centre and ancestral temple where he or she, or the parents, lived their mortal life. There are frequently disputes over which is the original place and source temple of the cult of a deity.[13]

God of Heaven

Chinese traditional theology, which comes in different interpretations according to the classic texts, and specifically Confucian, Taoist, and other philosophical formulations,[20] is fundamentally monistic, that is to say, it sees the world and the gods who produce it as an organic whole, or cosmos.[21] The universal principle that gives origin to the world is conceived as transcendent and immanent to creation, at the same time.[22] The Chinese idea of the universal God is expressed in different ways. There are many names of God from the different sources of Chinese tradition.[23]

The radical Chinese terms for the universal God are Tian (天) and Shangdi (上帝, "Highest Deity") or simply, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (帝, "Deity").[24][25] There is also the concept of Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (太帝, "Great Deity"). Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. is a title expressing dominance over the all-under-Heaven, that is, all things generated by Heaven and ordered by its cycles and by the stars.[26] Tian is usually translated as "Heaven", but by graphical etymology, it means "Great One" and a number of scholars relate it to the same Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. through phonetic etymology and trace their common root, through their archaic forms, respectively *Teeŋ and *Tees, to the symbols of the squared north celestial pole godhead (口, Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.).[3][27] These names are combined in different ways in Chinese theological literature, often interchanged in the same paragraph, if not in the same sentence.[28]

Names of the God of Heaven

Besides Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist., other names include Yudi ("Jade Deity") and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. ("Great Oneness") who, in mythical imagery, holds the ladle of the Big Dipper (Great Chariot), providing the movement of life to the world.[29] As the hub of the skies, the north celestial pole constellations are known, among various names, as Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天門, "Gate of Heaven")[30] and Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天樞, "Pivot of Heaven").[31]

Other names of the God of Heaven are attested in the vast Chinese religio-philosophical literary tradition:

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天帝), "Deity of Heaven" or "Emperor of Heaven":[32] "On Rectification" (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.) of the Xunzi uses this term to refer to the active God of Heaven setting creation in motion.[26]

- Tianzhu (天主), the "Lord of Heaven": In "The Document of Offering Sacrifices to Heaven and Earth on the Mountain Tai" (Fengshan shu) of the Records of the Grand Historian, it is used as the title of the first God from whom all the other gods derive.[33]

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天皇), the "August Personage of Heaven": In the "Poem of Fathoming Profundity" (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.), transcribed in "The History of the Later Han Dynasty" (Script error: The function "transl" does not exist.), Zhang Heng ornately writes: «I ask the superintendent of the Heavenly Gate to open the door and let me visit the King of Heaven at the Jade Palace».[32]

- Tianwang (天王), the "King of Heaven" or "Monarch of Heaven".

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天公), the "Duke of Heaven" or "General of Heaven".[34]

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天君), the "Prince of Heaven" or "Lord of Heaven".[34]

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天尊), the "Heavenly Venerable", also a title for high gods in Taoist theologies.[32]

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (天神), the "God of Heaven", interpreted in the Shuowen Jiezi as "the being that gives birth to all things".[26]

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (神皇), "God the August", attested in Taihong ("The Origin of Vital Breath").[26]

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (老天爺), the "Olden Heavenly Father".[32]

Tian is both transcendent and immanent, manifesting in the three forms of dominance, destiny, and nature of things. In the Wujing yiyi (五經異義, "Different Meanings in the Five Classics"), Xu Shen explains that the designation of Heaven is quintuple:[33]

- Huáng Tiān (皇天), "August Heaven" or "Imperial Heaven", when it is venerated as the lord of creation.

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (昊天), "Vast Heaven", with regard to the vastness of its vital breath (qi).

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (旻天), "Compassionate Heaven", for it hears and corresponds with justice to the all-under-Heaven.

- Script error: The function "transl" does not exist. (上天), "Highest Heaven" or "First Heaven", for it is the primordial being supervising all-under-Heaven.

- Cāng Tiān (蒼天), "Deep-Green Heaven", for it being unfathomably deep.

All these designations reflect a hierarchical, multiperspective experience of divinity.[23]

Lists of gods, deities and immortals

Many classical books have lists and hierarchies of gods and immortals, among which are the "Completed Record of Deities and Immortals" (神仙通鑑, Shénxiān Tōngjiàn) of the Ming dynasty,[35] and the Biographies of the Deities and Immortals (Shenxian Zhuan) by Ge Hong (284–343).[36] The older Collected Biographies of the Immortals (Liexian Zhuan) also serves the same purpose.

Couplets or polarities, such as Fuxi and Nuwa, Xiwangmu and Dongwanggong, and the highest couple of Heaven and Earth, all embody yin and yang and are at once the originators and maintainers of the ordering process of space and time.[37]

Immortals, or xian, are seen as a variety of different types of beings, including the souls of virtuous Taoists,[38] gods,[38][39] zhenren,[39] and/or a type of supernatural spiritual being who understood heaven.[40] Taoists historically worshiped them the most and Chinese folk religion practitioners during the Tang dynasty also worshiped them, although there was more skepticism about the goodness, and even the existence, of xian among them.[40]

Chinese folk religion that incorporates elements of the three teachings in modern times and prior eras sometimes viewed Confucius and the Buddha as immortals or beings synonymous to them.[41]

In Taoism and Chinese folk religion, gods and xian[42] are often seen as embodiments of water.[43] Water gods and xian were often thought to ensure good grain harvests, mild weather and seas, and rivers with abundant water.[43] Some xian were thought to be humans who gained power by drinking "charmed water".[42]

Some gods were based on previously existing Taoist immortals, bodhisattvas, or historical figures.[44]

Cosmic gods

- Yudi (玉帝, "Jade Deity") or Yuhuang (玉皇, "Jade Emperor" or "Jade King"), is the popular human-like representation of the God of Heaven.[45] Jade traditionally represents purity, so it is a metaphor for the unfathomable source of creation.

- Doumu (斗母, "Mother of the Great Chariot"), often entitled with the honorific Tianhou (天后, "Queen of Heaven")[lower-roman 1] is the heavenly goddess portrayed as the mother of the Big Dipper (Great Chariot), whose seven stars, in addition to two invisible ones, are conceived as her sons, the Jiuhuangshen (九皇神, "Nine God-Kings"), themselves regarded as the ninefold manifestation of Jiuhuangdadi (九皇大帝, "Great Deity of the Nine Kings") or Doufu (斗父, "Father of the Great Chariot"), another name of the God of Heaven. She is, therefore, both wife and mother of the God of Heaven.[46][47]

- Pangu (盤古), a macranthropic metaphor of the cosmos. He separated yin and yang, creating the earth (murky yin) and the sky (clear yang). All things were made from his body after he died.[48]

- Xiwangmu (西王母, "Queen Mother of the West"),[lower-roman 2] identified with the Kunlun Mountain, shamanic inspiration, death, and immortality.[50][51] She is the dark, chthonic goddess, pure yin, at the same time terrifying and benign, both creation and destruction, associated with the tiger and weaving.[52] Her male counterpart is Dongwanggong (東王公, "King Duke of the East";[lower-roman 3] also called Mugong, 木公 "Duke of the Woods"),[53] who represents the yang principle.[52]

- Hòuyì (后羿, "Yi the Archer"), was a man who sought for immortality, reaching Xiwangmu on her mountain, Kunlun.

- Yanwang (閻王, "Purgatory King")[lower-roman 4] the ruler of the underworld, assisted by the Heibai Wuchang (黑白無常, "Black and White Impermanence"), representing the alternation of yin and yang principles, alongside Ox-Head and Horse-Face, who escort spirits to his realm.

- Yinyanggong (陰陽公, "Yinyang Duke"[lower-roman 3]) or Yinyangsi (陰陽司, "Yinyang Controller"), the personification of the union of yin and yang.

Three Patrons and Five Deities

- Sānhuáng (三皇, "Three Patrons or Augusts") or Sāncái (三才, "Three Potencies"); they are the "vertical" manifestation of Heaven, spatially corresponding to the Sānjiè (三界, "Three Realms"), representing the yin and yang and the medium between them, that is the human being:

- Fuxi (伏羲) , the patron of heaven (天皇, Tiānhuáng), also called Bāguàzǔshī (八卦祖師, "Venerable Inventor of the Bagua") by the Taoists, is a divine man reputed to have taught to humanity writing, fishing, and hunting.

- Nüwa (女媧), the patron of earth (地皇, Dehuáng), is a goddess attributed for the creation of mankind and mending the order of the world when it was broken.

- Shennong (神農), "Peasant God", the patron of humanity (人皇, Rénhuáng), identified as Yandi (炎帝, "Flame Deity" or "Fiery Deity"), a divine man said to have taught the techniques of farming, herbal medicine, and marketing. He is often represented as a human with horns and other features of an ox.[56]

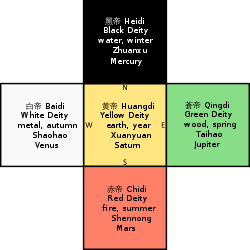

- Wǔdì (五帝, "Five Deities"),[57] also Wǔfāng Shàngdì (五方上帝, "Five Manifestations of the Highest Deity"), Wǔfāng Tiānshén (五方天神, "Five Manifestations of the Heavenly God"), Wǔfāngdì (五方帝, "Five Forms Deity"), Wǔtiāndì (五天帝, "Five Heavenly Deities"), Wǔlǎojūn (五老君, "Five Ancient Lords"), Wǔdàoshén (五道神, "Five Ways God[s]"); they are the five main "horizontal" manifestations of Heaven, and along with the Three Potencies, they have a celestial, a terrestrial, and a chthonic form. They correspond to the five phases of creation, the five constellations rotating around the celestial pole and five planets, the five sacred mountains and five directions of space (their terrestrial form), and the five Dragon Gods which represent their mounts, that is to say, the material forces they preside over (their chthonic form).[58][59]

- Huangdi (黃帝, "Yellow Emperor" or "Yellow Deity"); or Huángshén (黃神, "Yellow God"), also known as Xuānyuán Huángdì (軒轅黃帝, "Yellow Deity of the Chariot Shaft"), is the Zhōngyuèdàdì (中岳大帝, "Great Deity of the Central Peak"): he represents the essence of earth and the Yellow Dragon,[56] and is associated with Saturn.[59] The character 黃 (huáng, "yellow"), by homophony and shared etymology with 皇 (huáng), also means "august", "creator", and "radiant", identifying the Yellow Emperor with Shangdi ("Highest Deity").[60] Huangdi represents the heart of creation, the axis mundi (Kunlun) that is the manifestation of the divine order in physical reality, opening the way to immortality.[56] As the deity of the centre, intersecting the Three Patrons and the Five Deities, in the Shizi he is described as "Yellow Emperor with Four Faces" (黃帝四面, Huángdì Sìmiàn).[61] As a human, he is said to have been the fruit of a virginal birth, as his mother Fubao conceived him as she was aroused, while walking in the country, by a lightning from the Big Dipper (Great Chariot). She delivered her son after twenty-four months on the mount of Shou (Longevity) or mount Xuanyuan (Chariot Shaft), after which he was named.[62] He is reputed to be the founder of the Huaxia civilisation, and the Han Chinese identify themselves as the descendants of Yandi and Huangdi.

- Cangdi (蒼帝, "Green Deity); or Qīngdì (青帝, "Blue Deity" or "Bluegreen Deity", the Dōngdì (東帝, "East Deity") or Dōngyuèdàdì (東岳大帝, "Great Deity of the Eastern Peak"): he is Tàihào (太昊), associated with the essence of wood and with Jupiter, and is the god of fertility and spring. The Bluegreen Dragon is both his animal form and constellation.[56][59] His female consort is the goddess of fertility, Bixia.

- Heidi (黑帝, "Black Deity), the Běidì (北帝, "North Deity") or Běiyuèdàdì (北岳大帝, "Great Deity of the Northern Peak"): he is Zhuanxu (顓頊), today frequently worshiped as Xuanwu (玄武, "Dark Warrior") or Zhēnwǔ (真武), and is associated with the essence of water and winter, and with Mercury. His animal form is the Black Dragon and his stellar animal is the tortoise-snake.[56][59]

- Chidi (赤帝, "Red Deity"), the Nándì (帝, "South Deity") or Nányuèdàdì (南岳大帝, "Great Deity of the Southern Peak"): he is Shennong (the "Divine Farmer"), the Yandi ("Fiery Deity"), associated with the essence of fire and summer, and with Mars. His animal form is the Red Dragon and his stellar animal is the phoenix. He is the god of agriculture, animal husbandry, medicinal plants, and market.[56][59]

- Baidi (白帝, "White Deity"), the Xīdì (西帝, "West Deity") or Xīyuèdàdì (西岳大帝, "Great Deity of the Western Peak"): he is Shaohao (少昊), and is the god of the essence of metal and autumn, associated with Venus. His animal form is the White Dragon and his stellar animal is the tiger.[59]

- The Three Great Emperor-Officials: the Tiānguān (天官, "Official of Heaven"), the Dìguān (地官, "Official of Earth"), and the Shuǐguān (水官, "Official of Water").[63][64]

In mythology, Huangdi and Yandi fought a battle against each other, and Huang finally defeated Yan with the help of the Dragon (the controller of water, who is Huangdi himself).[65] This myth symbolizes the equipoise of yin and yang, here the fire of knowledge (reason and craft) and earthly stability.[65]

Yan (炎) is flame, scorching fire, or an excess of it (it is important to note that graphically, it is a double 火 (huo, "fire").[65] As an excess of fire brings destruction to the earth, it has to be controlled by a ruling principle. Nothing is good in itself, without limits; good outcomes depend on the proportion in the composition of things and their interactions, never on extremes in absolute terms.[65] Huangdi and Yandi are complementary opposites, necessary for the existence of one another, and they are powers that exist together within the human being.

Gods of celestial and terrestrial phenomena

- Longshen (龍神, "Dragon Gods") or Lóngwáng, (龍王, "Dragon Kings"), also Sìhǎi Lóngwáng (四海龍王, "Dragon Kings of the Four Seas"), are gods of watery sources, usually reduced to four, patrons of the Four Seas (四海, sihai) and the four cardinal directions. They are the White Dragon (白龍, Báilóng), the Black Dragon (玄龍, Xuánlóng), the Red Dragon (朱龍, Zhūlóng), and the Bluegreen Dragon (青龍, Qīnglóng). Corresponding with the Five Deities as the chthonic forces that they sublimate (the Dragon Gods are often represented as the "mount" of the Five Deities), they inscribe the land of China into an ideal sacred squared boundary. The fifth dragon, the Yellow Dragon (黃龍, Huánglóng), is the dragon of the centre, representing the Yellow God.

- Báoshén (雹神, "Hail God")[lower-roman 4]

- Bālà (八蜡), the Chóngshén (蟲神, "Insect God") or Chóngwáng (蟲王, "Insect King"): the gods of insects.[lower-roman 4]

- Dìzhǔshén (地主神, "Landlord God").

- Dòushén (痘神, "Smallpox God").[lower-roman 4]

- Fei Lian (飛帘), the Fēngshén (風神, "Wind God").[lower-roman 4]

- Hǎishén (海神, "Sea God"); also Hǎiyé (海爷, "Sea Lord").

- Hebo (河伯, "River Lord") or Héshén (河神, "River God"): any watercourse god, among which, one of the most revered is the god of the Yellow River.[lower-roman 4]

- Gǔshén (穀神, "Valley God"): in the Daodejing, a name used to refer to the Way[68]

- Huǒshén (火神, "Fire God"), often personified as Zhurong (祝融)[lower-roman 4]

- Húshén (湖神, "Lake God")

- Shèshén (社神, "Soil God")

- Jìshén (稷神, "Grain God")

- Jīnshén (金神, "Gold God"), often identified as the Qiūshén (秋神, "Autumn God") and personified as Rùshōu (蓐收)

- Jǐngshén (井神, "Waterspring God").[68]

- Leishen (雷神, "Thunder God") or Léigōng (雷公, "Thunder Duke");[lower-roman 3] his consort is Diànmǔ (電母, "Lightning Mother").

- Mùshén (木神, "Woodland God"), usually the same as the Chūnshén (春神, "Spring God"), and as Jùmáng (句芒).

- Shānshén (山神, "Mountain God")

- Shuǐshén (水神, "Water God")

- Tudishen (土地神, "God of the Local Land"), also Tǔshén (土神, "Earth God"), or Tudigong (土地公, "Duke of the Local Land"):[lower-roman 3] the tutelary deity of any locality. Their Overlord is Houtu (后土, "Queen of the Earth").[lower-roman 2]

- Wen Shen (瘟神, "Plague God")[lower-roman 4]

- Xiangshuishen (湘水神, "Xiang Waters' Goddesses"): the patrons of the Xiang River.

- Xuěshén (雪神, "Snow God")

- Yǔshén (雨神, "Rain God")[lower-roman 4]

- Xihe (羲和), the Tàiyángshén (太陽神, "Great Sun Goddess") or Shírìzhīmǔ (十日之母, "Mother of the Ten Suns").[lower-roman 2]

- Yuèshén (月神, "Moon Goddesses"): Chángxī (常羲) or Shí'èryuèzhīmǔ (十二月之母, "Mother of the Twelve Moons"), and Chang'e (嫦娥).

Gods of human virtues and crafts

Some Taoist gods were thought to affect human morality and the consequences of it in certain traditions. Some Taoists beseeched gods, multiple gods, and/or pantheons to aid them in life and/or abolish their sins.[69]

- Civil and military (wen and wu) deities:

- Wendi (文帝, "Culture Deity"), also Wénchāngdì (文昌帝, "Deity who Makes Culture Thrive") or Wénchāngwáng (文昌王, "King who Makes Culture Thrive"): in southern provinces, this deity takes the identity of various historical persons, while in the north, he is more frequently identified as being the same as Confucius (孔夫子, Kǒngfūzǐ)

- Kuixing (魁星, "Chief Star"): another god of culture and literature, but specifically, examination, is a personification of the man who awakens to the order of the Great Chariot.

- Wǔdì (武帝, "Military Deity"): Guandì (關帝, "Divus Guan"), also called Guāngōng (關公, "Duke Guan"),[lower-roman 3] and popularly Guānyǔ (關羽).[lower-roman 2]

- Wendi (文帝, "Culture Deity"), also Wénchāngdì (文昌帝, "Deity who Makes Culture Thrive") or Wénchāngwáng (文昌王, "King who Makes Culture Thrive"): in southern provinces, this deity takes the identity of various historical persons, while in the north, he is more frequently identified as being the same as Confucius (孔夫子, Kǒngfūzǐ)

- Baoshengdadi (保生大帝, "Great Deity who Protects Life").[lower-roman 5]

- Baxian (八仙, "Eight Immortals").

- Canshen (蠶神, "Silkworm God"), who may be:

- Cánmǔ (蠶母, "Silkworm Mother"), also called Cángū (蠶姑, "Silkworm Maiden"), who is identified as Leizu (嫘祖), the wife of the Yellow Emperor: the invention of sericulture is attributed primarily to her.

- Qīngyīshén (青衣神, "Bluegreen-Clad God"): his name as a human was Cáncóng (蠶叢, "Silkworm Twig"), and he is the first ruler and ancestor of the Shu state and promoter of sericulture among his people.

- Caishen (財神, "Wealth God").[lower-roman 2]

- Cangjie (倉頡), the four-eyed inventor of the Chinese characters.

- Cāngshén (倉神, "Granary God").

- Chuānzhǔ (川主, "Lord of Sichuan")

- Chenghuangshen (城隍神, "Moat and Walls God", or "Boundary God"): the god of the sacred boundaries of a human agglomeration, he is often personified by founding fathers or noble personalities from each city or town.[lower-roman 2]

- Chen Jinggu (陳靖姑, "Old Quiet Lady"), also called Línshuǐ Fūrén (臨水夫人, "Waterside Dame").[lower-roman 5]

- Hùshén (戶神, "Gate God").

- Chēshén (車神, "Vehicle God")[lower-roman 4]

- Erlangshen (二郎神, "Twice Young God"), the god of engineering.

- Guǎngzé Zūnwáng (廣澤尊王, "Honorific King of Great Compassion").[lower-roman 5]

- Guanyin (觀音, "She who Hears the Cries of the World"), the goddess of mercy.[lower-roman 2]

- Huang Daxian (黃大仙, "Great Immortal Huang").

- Jigong (濟公, "Help Lord").

- Jiǔshén (酒神, "Wine God"), personified as Yidi (儀狄).[lower-roman 4]

- Jiutian Xuannü (九天玄女, "Mysterious Lady of the Nine Heavens"), a disciple of Xiwangmu and initiator of Huangdi.

- Longmu (龍母, "Dragon Mother").

- Lu Ban (魯班), the god of carpentry.

- Lùshén (路神, "Road God").[lower-roman 4]

- Xíngshén (行神, "Walking God").

- Mazu (媽祖, "Ancestral Mother"), often entitled the "Queen of Heaven".[lower-roman 1][lower-roman 6]

- Pànguān (判官, "Judging Official").

- Píng'ānshén (平安神, "Peace God"), an embodiment of whom is considered to have been Mao Zedong.[71]

- Qingshui Zushi (清水祖師, "Venerable Patriarch of the Clear Stream")[lower-roman 5]

- Táoshén (陶神, "Pottery God")[lower-roman 4]

- Tuershen (兔兒神, "Leveret God"), the god of love among males.

- Tuōtǎlǐ Tiānwáng (托塔李天王, "Pagoda-Bearing Heavenly King"), also known as Li Jing (李靖). He has three sons, the warlike protector deities Jinzha (金吒), Muzha (木吒), and Nezha (哪吒).

- Wǔxiǎn (五顯, "Five Shining Ones"), possibly a popular form of the cosmological Five Deities.[lower-roman 5]

- Xǐshén (喜神, "Joy God").

- Yàoshén (藥神, "Medicine God") or frequently Yàowáng (藥王, "Medicine King").[lower-roman 4]

- Yuexia Laoren (月下老人, "Old Man Under the Moon"), the matchmaker who pairs lovers together.

- Yùshén (獄神, "Jail-Purgatory God")[lower-roman 4]

- Zaoshen (灶神, "Hearth God"), the master of the household deities, including the "Bed God" (床神, Chuángshén), the "Gate Gods" (門神, Ménshén), and the "Toilet god" (廁神, Cèshén), often personified as Zigu.

- Zhong Kui (鍾馗), the vanquisher of ghosts and evil beings.

- Sanxing (三星, "Three Stars"), a cluster of three astral gods of well-being:

Gods of animal and vegetal life

- Huāshén (花神, "Flower Goddess").

- Huxian (狐神, "Fox God[dess]") or Húxiān (狐仙, "Fox Immortal"), also called Húxiān Niángniáng (狐仙娘娘, "Fox Immortal Lady").[lower-roman 7]

- Two other great fox deities, peculiar to northeast China, are the "Great Lord of the Three Foxes" (胡三太爷, Húsān Tàiyé) and the "Great Lady of the Three Foxes" (胡三太奶, Húsān Tàinǎi), representing the yin and yang.[lower-roman 7]

- Mǎshén (馬神, "Horse God") or Mǎwáng (马王, "Horse King").[lower-roman 4]

- Niúshén (牛神, "Cattle God" or "Ox God"), also called Niúwáng (牛王, "Cattle King").[lower-roman 4]

- Lángshén (狼神, "Wolf God").[lower-roman 4]

- Shùshén (樹神, "Tree God[s]").

- Wǔgǔshén (五谷神, "Five Cereals God"),[lower-roman 4] another name for Shennong.

- Yuánshén (猿神, "Monkey God") or Yuánwáng (猿王, "Monkey King"), who is identified as Sun Wukong (孙悟空).[lower-roman 8]

- Zhīmáshén (芝蔴神, "Sesame God")[lower-roman 4]

Bixia mother goddess worship

The worship of mother goddesses for the cultivation of offspring is present all over China, but predominantly in northern provinces. There are nine main goddesses, and all of them tend to be considered as manifestations or attendant forces of a singular goddess identified variously as Bixia Yuanjun (碧霞元君, "Lady of the Blue Dawn"), also known as the Tiānxiān Niángniáng (天仙娘娘, "Heavenly Immortal Lady") or Tàishān Niángniáng (泰山娘娘, "Lady of Mount Tai"),[lower-roman 9] or also Jiǔtiān Shèngmǔ (九天聖母,[73] "Holy Mother of the Nine Skies"[lower-roman 10])[74]:149–150 or Houtu, the goddess of the earth.[75]

Bixia herself is identified by Taoists as the more ancient goddess Xiwangmu.[76] The general Chinese term for "goddess" is nǚshén (女神), and goddesses may receive many qualifying titles, including mǔ (母, "mother"), lǎomǔ (老母, "old mother"), shèngmǔ (聖母, "holy mother"), niángniáng (娘娘, "lady"), nǎinai (奶奶, "granny").

The additional eight main goddesses of fertility, reproduction, and growth are:[74]:149–150; 191, note 18

- Bānzhěn Niángniáng (瘢疹娘娘), the goddess who protects children from illness.

- Cuīshēng Niángniáng (催生娘娘), the goddess who gives swift childbirth and protects midwives.

- Nǎimǔ Niángniáng (奶母娘娘), the goddess who presides over maternal milk and protects nursing.

- Péigū Niángniáng (培姑娘娘), the goddess who cultivates children.

- Péiyǎng Niángniáng (培養娘娘), the goddess who protects the upbringing of children.

- Songzi Niangniang (送子娘娘) or Zǐsūn Niángniáng (子孫娘娘), the goddess who presides over offspring.

- Yǎnguāng Niángniáng (眼光娘娘), the goddess who protects eyesight.

- Yǐnméng Niángniáng (引蒙娘娘), the goddess who guides young children.

Altars of goddess worship are usually arranged with Bixia at the center and two goddesses at her sides, most frequently the "Lady of Eyesight" and the "Lady of Offspring".[74]:149–150; 191, note 18 A different figure, but with the same astral connections as Bixia is the "Goddess of the Seven Stars" (七星娘娘, Qīxīng Niángniáng).[lower-roman 11]

There is also the cluster of the "Holy Mothers of the Three Skies" (三霄聖母, Sānxiāo Shèngmǔ; or 三霄娘娘, Sānxiāo Niángniáng, "Ladies of the Three Stars"), composed of Yunxiao Guniang, Qiongxiao Guniang, and Bixiao Guniang.[77] The cult of Chenjinggu, present in southeast China, is identified by some scholars as an emanation of the northern cult of Bixia.[78]

Other goddesses worshipped in China include Cánmǔ (蠶母, "Silkworm Mother") or Cángū (蠶姑, "Silkworm Maiden"),[79] identified with Leizu (嫘祖, the wife of the Yellow Emperor), Magu (麻姑, "Hemp Maiden"), Sǎoqīng Niángniáng (掃清娘娘, "Goddess who Sweeps Clean"),[lower-roman 12][80] Sānzhōu Niángniáng (三洲娘娘, "Goddess of the Three Isles"),[80] and Wusheng Laomu. The mother goddess is central in the theology of many folk religious sects.[79]

Gods of northeast China

Northeast China has clusters of deities which are peculiar to the area, deriving from the Manchu and broader Tungusic substratum of the local population. Animal deities related to shamanic practices are characteristic of the area and reflect wider Chinese cosmology. Besides the aforementioned Fox Gods (狐仙, Húxiān), they include:[citation needed]

- Huángxiān (黃仙, "Yellow Immortal", the Weasel God.

- Shéxiān (蛇仙, "Snake Immortal"), also variously called Liǔxiān (柳仙, "Immortal Liu"), or Chángxiān (常仙, "Viper Immortal") or also Mǎngxiān (蟒仙, "Python or Boa Immortal").

- Báixiān (白仙, "White Immortal"), the Hedgehog God.

- Hēixiān (黑仙, "Black Immortal"), who may be the Wūyāxiān (烏鴉仙, "Crow Immortal"), or the Huīxiān (灰仙, "Rat Immortal"), with the latter considered a misinterpretation of the former.

Gods of Indian origin

Gods who have been adopted into Chinese religion but who have their origins in the Indian subcontinent or Hinduism:

- Guanin (觀音, "She who Hears the Cries of the World"), a Chinese goddess of mercy modeled after the bodhisattva Avalokiteśvara

- Sìmiànshén (四面神, "Four-Faced God"), but also a metaphor for "Ubiquitous God": The recent cult has its origin in the Thai transmission of the Hindu god Brahma, but it is important to note that it is also an epithet of the indigenous Chinese god Huangdi who, as the deity of the centre of the cosmos, is described in the Shizi as "Yellow Emperor with Four Faces" (黃帝四面, Huángdì Sìmiàn).[61]

- Xiàngtóushén (象頭神, "Elephant-Head God"), is the Indian god Ganesha.[81]

Gods of North China and Mongolia

- Genghis Khan (成吉思汗, Chéngjísīhán), worshipped by Mongols and Chinese under a variety of divinity titles, including Shèngwǔ Huángdì (聖武皇帝, "Holy Military Sovereign Deity"), Fǎtiān Qǐyùn (法天啓運, "Starter of the Transmission of the Law of Heaven"), and Tàizǔ (太祖, "Great Ancestor") of the Yuan and the Mongols.

Gods of Folk and Local

- Heng and Ha (哼哈二將), two generals of the Shang dynasty, guards of Buddhist temples in East Asia.[82]

- Menshen (門神, "Door Gods"), divine guardians of doors and gates.

- Shentu and Yulü (鬱壘), a pair of deities who punished evil spirits.

See also

- Chinese folk religion

- Chinese temple

- Jiutian Xuannü, Powerful female Deity in Chinese folk religion

- Mongolian shamanism

- Shen

- Shi Gandang, protector of home

- Xian, a commonly used Chinese word to refer to what are called "Taoist immortals" in English

- Zhenren

Notes

- ↑ Whether centred in the change-ful precessional north celestial pole or in the fixed north ecliptic pole, the spinning constellations draw the 卍 symbol around the centre.

- Notes about the deities and their names

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 The honorific Tiānhòu (天后 "Queen of Heaven") is used for many goddesses, but most frequently Mazu and Doumu.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 The cult of this deity is historically exercised all over China.[49]

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 About the use of the title "duke": the term is from Latin dux, and describes a phenomenon or person who "conducts", "leads", the divine inspiration.

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 4.13 4.14 4.15 4.16 4.17 4.18 4.19 The cult of this deity is historically exercised in northern China.[54] It is important to note that many cults of northern deities were transplanted also in southern big cities like Hong Kong and Macau, and also in Taiwan, with the political changes and migrations of the 19th and 20th centuries.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 The cult of this deity is historically exercised in southeastern China.[49]

- ↑ The cult of Mazu has its origin in Fujian, but it has expanded throughout southern China and in many northern provinces, chiefly in localities along the coast, as well as among expatriate Chinese communities.[70]

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The cult of fox deities is characteristic of northeastern China's folk religion, with influences reaching as far south as Hebei and Shandong.

- ↑ The worship of monkeys in the northern Fujian region has a long history. Influenced by Journey to the West, the worship of the Monkey God in some areas has gradually been replaced by the worship of the Qítiān Dàshèng.[72]

- ↑ As the Lady of Mount Tai, Bixia is regarded as the female counterpart of Dongyuedadi, the "Great Deity of the Eastern Peak" (Mount Tai).

- ↑ The "Nine Skies" (九天 Jiǔtiān) are the nine stars (seven stars with the addition of two invisibile ones, according to the Chinese tradition) of the Big Dipper or Great Chariot. Thus, Bixia and her nine attendants or manifestations are at the same time a metaphorical representation of living matter or earth, and of the source of all being which is more abstractly represented by major axial gods of Chinese religion such as Doumu.

- ↑ Qixing Niangniang ("Lady of the Seven Stars") is a goddess that represents the seven visible stars of the Big Dipper or Great Chariot.

- ↑ Saoqing Niangniang ("Lady who Sweeps Clean") is the goddess who ensures good weather conditions "sweeping away" clouds and storms.

References

Citations

- ↑ Lü & Gong (2014), p. 71.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "tian" (in en). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/tian.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Didier (2009), passim.

- ↑ Zhong (2014), pp. 76–77.

- ↑ Zhong (2014), p. 84, note 282.

- ↑ "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". http://web.sgjh.tn.edu.tw/cyberfair/treeking/story/story_2_3.htm. - ↑ Zhong (2014), p. 98 ff.

- ↑ Zhao (2012), p. 45.

- ↑ "Sanguan" (in en). Encyclopedia Britannica. 2010-02-03. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sanguan.

- ↑ Zhong (2014), p. 202.

- ↑ Zhong (2014), p. 64.

- ↑ Zhong (2014), pp. 31, 173–174.

- ↑ Feuchtwang (2016), p. 147.

- ↑ Didier (2009), p. 256, Vol. III.

- ↑ Mair, Victor H. (2012). "Religious Formations and Intercultural Contacts in Early China". in Krech, Volkhard. Dynamics in the History of Religions between Asia and Europe: Encounters, Notions, and Comparative Perspectives. Leiden: Brill. pp. 85–110. doi:10.1163/9789004225350_005. ISBN 978-90-04-22535-0. pp. 97–98, note 26.

- ↑ Didier (2009), p. 257, Vol. I.

- ↑ Reiter, Florian C. (2007). Purposes, Means and Convictions in Daoism: A Berlin Symposium. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. p. 190. ISBN 978-3-447-05513-0.

- ↑ Milburn, Olivia (2016). The Spring and Autumn Annals of Master Yan. Sinica Leidensia. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-30966-1. p. 343, note 17.

- ↑ Assasi, Reza (2013). "Swastika: The Forgotten Constellation Representing the Chariot of Mithras". Anthropological Notebooks XIX (2). ISSN 1408-032X. https://www.academia.edu/4087681.

- ↑ Adler (2011), pp. 4–5.

- ↑ Cai (2004), p. 314.

- ↑ Adler (2011), p. 5.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Lü & Gong (2014), p. 63.

- ↑ Chang (2000).

- ↑ Lü & Gong (2014), pp. 63–67.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 Lü & Gong (2014), p. 64.

- ↑ Zhou (2005).

- ↑ Zhong (2014), p. 66, note 224.

- ↑ Lagerwey & Kalinowski (2008), p. 240.

- ↑ Reiter, Florian C. (2007). Purposes, Means and Convictions in Daoism: A Berlin Symposium. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3447055130. p. 190.

- ↑ Milburn, Olivia (2016). The Spring and Autumn Annals of Master Yan. Sinica Leidensia. BRILL. ISBN 978-9004309661. p. 343, note 17.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 Lü & Gong (2014), p. 66.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Lü & Gong (2014), p. 65.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Lagerwey & Kalinowski (2008), p. 981.

- ↑ Yao (2010), p. 159.

- ↑ Yao (2010), p. 161.

- ↑ Lagerwey & Kalinowski (2008), p. 984.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "xian" (in en). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/xian-Daoism.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "zhenren" (in en). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/zhenren.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Chua, Amy (2007). Day of Empire: How Hyperpowers Rise to Global Dominance–and Why They Fall (1st ed.). New York: Doubleday. pp. 65. ISBN 978-0-385-51284-8. OCLC 123079516. https://www.worldcat.org/oclc/123079516.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Philip (1999). Spilling, Michael. ed. Illustrated Dictionary of Religions (First American ed.). New York: DK. pp. 67. ISBN 0-7894-4711-8.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Mackenzie, Donald Alexander (1986). China & Japan (Myths and Legends). New York: Avenel Books. pp. 318. ISBN 9780517604465.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Jian-guang, Wang (December 2019). "Water Philosophy in Ancient Society of China: Connotation, Representation, and Influence". Philosophy Study 9 (12): 752. https://www.davidpublisher.com/Public/uploads/Contribute/5e05a4e1c4c77.pdf.

- ↑ Jiangshan, Wang, ed (October 2020). Imperial China: The Definitive Visual History (First American ed.). New York: DK. pp. 112. ISBN 978-0-7440-2047-2.

- ↑ Pregadio (2013), p. 1197.

- ↑ Cheu, Hock Tong (1988). The Nine Emperor Gods: A Study of Chinese Spirit-medium Cults. Time Books International. ISBN 9971653850. p. 19.

- ↑ DeBernardi, Jean (2007). "Commodifying Blessings: Celebrating the Double-Yang Festival in Penang, Malaysia and Wudang Mountain, China". in Kitiarsa, Pattana. Religious Commodifications in Asia: Marketing Gods. Routledge. ISBN 978-1134074457.

- ↑ Pregadio (2013), pp. 76, 1193.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Overmyer (2009), p. 148.

- ↑ Lagerwey & Kalinowski (2008), p. 983.

- ↑ Max Dashu (2010). "Xiwangmu: The Shamanic Great Goddess of China". https://www.academia.edu/4075136.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Fowler (2005), pp. 206–207.

- ↑ Lagerwey & Kalinowski (2008), p. 512.

- ↑ Overmyer (2009), passim chapter 5: "Gods and Temples".

- ↑ Sun & Kistemaker (1997), p. 121.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 56.4 56.5 Fowler (2005), pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Medhurst (1847), p. 260.

- ↑ Little & Eichman (2000), p. 250. It describes a Ming dynasty painting representing (among other figures) the Wudi: "In the foreground are the gods of the Five Directions, dressed as emperors of high antiquity, holding tablets of rank in front of them. [...] These gods are significant because they reflect the cosmic structure of the world, in which yin, yang and the Five Phases (Elements) are in balance. They predate religious Taoism, and may have originated as chthonic gods of the Neolithic period. Governing all directions (east, south, west, north and center), they correspond not only to the Five Elements, but to the seasons, the Five Sacred Peaks, the Five Planets, and zodiac symbols as well. [...]".

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 59.2 59.3 59.4 59.5 Sun & Kistemaker (1997), pp. 120–123.

- ↑ Pregadio (2013), pp. 504–505.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Sun & Kistemaker (1997), p. 120.

- ↑ Bonnefoy, Yves (1993). Asian Mythologies. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226064565. p. 246.

- ↑ "Sanguan" (in en). Encyclopedia Britannica. 2010-02-03. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Sanguan.

- ↑ Adler, Joseph A.. "The Three Officials". Kenyon College. https://www2.kenyon.edu/Depts/Religion/Fac/Adler/Reln472/triptych.htm.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 Lee, Keekok (2008). Warp and Weft, Chinese Language and Culture. Strategic Book Publishing. ISBN 978-1606932476. pp. 156-157

- ↑ Sun Kun (29 March 2021). "不守常规的龙天庙" (in zh-cn). Taiyuan Daily. http://epaper.tyrbw.com/tyrb/html/2021-03/29/content_7_15798.htm.

- ↑ Wang Chunsheng (3 March 2022). "二月二习俗杂谈" (in zh-cn). Taiyuan Daily. http://epaper.tyrbw.com/tyrb/html/2022-03/03/content_7_79369.htm.

- ↑ 68.0 68.1 Yao (2010), p. 202.

- ↑ Wilson, Andrew, ed (1995). World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts (1st paperback ed.). St. Paul, Minnesota: Paragon House Publishers. pp. 20. ISBN 978-1-55778-723-1.

- ↑ Overmyer (2009), p. 144.

- ↑ Tvetene Malme, Erik (2014). "Error: no

|title=specified when using {{Cite web}}". University of Oslo. pp. 14-20, 23, 26-28, 33, 36. https://www.duo.uio.no/bitstream/handle/10852/40804/Master-thesis-KIN4593--Eirik-Tvetene-Malme.pdf?sequence=1. - ↑ ""齐天大圣"在福建,比《西游记》还要早几百年" (in zh-cn). The Paper. 27 January 2023. https://www.thepaper.cn/newsDetail_forward_21696656.

- ↑ Overmyer (2009), p. 137.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 Barrott Wicks, Ann Elizabeth (2002). Children in Chinese Art. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824823591.

- ↑ Jones (2013), pp. 166-167.

- ↑ Komjathy, Louis (2013). "Daoist deities and pantheons". The Daoist Tradition: An Introduction. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-1441196453.

- ↑ Overmyer (2009), p. 135.

- ↑ Hackin, J. (1932). Asiatic Mythology: A Detailed Description and Explanation of the Mythologies of All the Great Nations of Asia. Asian Educational Services. pp. 349–350.

- ↑ 79.0 79.1 Jones (2013), pp. 166–167.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 Chamberlain (2009), p. 235.

- ↑ Martin-Dubost, Paul (1997). Gaņeśa: The Enchanter of the Three Worlds. Mumbai: Project for Indian Cultural Studies. ISBN 8190018434. p. 311.

- ↑ Zi Yan (2012), p. 25–26.

Sources

- Adler, Joseph A. (2011). "The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China". (Conference paper) Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought. San Diego, CA. http://www2.kenyon.edu/Depts/Religion/Fac/Adler/Writings/Non-theistic.pdf.

- Cai, Zongqi (2004). Chinese Aesthetics: Ordering of Literature, the Arts, and the Universe in the Six Dynasties. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 0824827910.

- Chamberlain, Jonathan (2009). Chinese Gods : An Introduction to Chinese Folk Religion. Hong Kong: Blacksmith Books. ISBN 9789881774217.

- Chang, Ruth H. (2000). "Understanding Di and Tian: Deity and Heaven from Shang to Tang Dynasties". Sino-Platonic Papers (Victor H. Mair) (108). ISSN 2157-9679. http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp108_chinese_deity_heaven.pdf.

- Didier, John C. (2009). "In and Outside the Square: The Sky and the Power of Belief in Ancient China and the World, c. 4500 BC – AD 200". Sino-Platonic Papers (Victor H. Mair) (192). Volume I: The Ancient Eurasian World and the Celestial Pivot, Volume II: Representations and Identities of High Powers in Neolithic and Bronze China, Volume III: Terrestrial and Celestial Transformations in Zhou and Early-Imperial China.

- "Chinese religions", Religions in the Modern World: Traditions and Transformations (3nd ed.), London: Routledge, 2016, pp. 143–172, ISBN 978-1317439608

- Jones, Stephen (2013). In Search of the Folk Daoists of North China. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-1409481300.

- Early Chinese Religion: Part One: Shang Through Han (1250 BC-220 AD). Leiden: Brill. 2008. ISBN 978-9004168350.

- Little, Stephen; Eichman, Shawn (2000). Taoism and the Arts of China. University of California Press. ISBN 0520227859. https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_5ame4Rl1RXMC.

- Lü, Daji; Gong, Xuezeng (2014). Marxism and Religion. Religious Studies in Contemporary China. Brill. ISBN 978-9047428022. https://books.google.com/books?id=6r0FAwAAQBAJ.

- Medhurst, Walter H. (1847). A Dissertation on the Theology of the Chinese, with a View to the Elucidation of the Most Appropriate Term for Expressing the Deity, in the Chinese Language. Mission Press. https://archive.org/details/pli.kerala.rare.13521. Original preserved at The British Library. Digitalised in 2014.

- Overmyer, Daniel L. (2009). Local Religion in North China in the Twentieth Century the Structure and Organization of Community Rituals and Beliefs. Leiden; Boston: Brill. ISBN 9789047429364. http://cnqzu.com/library/To%20Organize/Books/Brill%20Ebooks/Brill._Handbook_of_Oriental_Studies/Brill.%20Handbook%20of%20Oriental%20Studies/Local_Religion_in_North_China_in_the_Twentieth_Century__Handbook_of_Oriental_Studies_.pdf. Retrieved 2016-07-22.

- Pregadio, Fabrizio (2013). The Encyclopedia of Taoism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1135796341. https://books.google.com/books?id=R3Sp6TfzhpIC. Two volumes: 1) A-L; 2) L-Z.

- Sun, Xiaochun; Kistemaker, Jacob (1997). The Chinese Sky During the Han: Constellating Stars and Society. Brill. ISBN 9004107371. https://books.google.com/books?id=87lvBoFi8A0C.

- Yao, Xinzhong (2010). Chinese Religion: A Contextual Approach. London: A&C Black. ISBN 9781847064752. https://books.google.com/books?id=GuINLKnJp0AC.

- Zhong, Xinzi (2014). A Reconstruction of Zhū Xī's Religious Philosophy Inspired by Leibniz: The Natural Theology of Heaven (Thesis). Open Access Theses and Dissertations. Hong Kong Baptist University Institutional Repository. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-02-28.

- Zhao, Dunhua (2012), "The Chinese Path to Polytheism", in Wang, Robin R., Chinese Philosophy in an Era of Globalization, SUNY Press, ISBN 978-0791485507, https://books.google.com/books?id=7BMp7VT7G4oC

- Zhou, Jixu (2005). "Old Chinese "*tees" and Proto-Indo-European "*deus": Similarity in Religious Ideas and a Common Source in Linguistics". Sino-Platonic Papers (Victor H. Mair) (167). http://www.sino-platonic.org/complete/spp167_old_chinese_proto_indo_european.pdf.

- Zi Yan (2012-08-01). Famous Temples in China. Beijing: Time Publishing and Media Co., Ltd.. ISBN 978-7-5461-3146-7.

|