Religion:Finnish Orthodox Church

Template:Infobox Orthodox Church The Finnish Orthodox Church (Finnish: Suomen ortodoksinen kirkko; Swedish: Finska Ortodoxa Kyrkan), or Orthodox Church of Finland, is an autonomous Eastern Orthodox archdiocese of the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. The Church has a legal position as a national church in the country, along with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland.[1]

With its roots in the medieval Novgorodian missionary work in Karelia, the Finnish Orthodox Church was a part of the Russian Orthodox Church until 1923. Today the church has three dioceses and 60,000 members that account for 1.1 percent of the native population of Finland . The parish of Helsinki has the most adherents.

Structure and organization

Along with the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, the Orthodox Church of Finland has a special position in Finnish law.[2] The church is considered to be a Finnish entity of public nature. The external form of the church is regulated by an Act of Parliament, while the spiritual and doctrinal matters of the church are legislated by the central synod of the church. The church has the right to tax its members and corporations owned by its members. Previously under the Russian Orthodox Church, it has been an autonomous Orthodox archdiocese of the Patriarchate of Constantinople since 1923.[3]

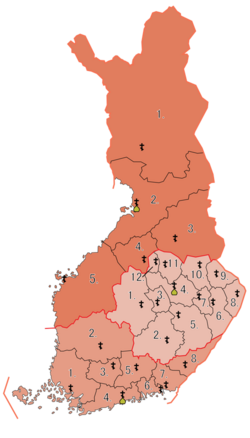

The Finnish Orthodox Church is divided into three dioceses (hiippakunta), each with a subdivision of parishes (seurakunta). There are 21 parishes with 140 priests and more than 58,000 members[4] in total. The number of church members has been steadily growing for several years.[5][6] A convent and a monastery also operate within the church.

The central legislative organ of the church is the central synod which is formed of

- bishops and coadjutor bishops,

- eleven priests

- three cantors

- eighteen laymen and -women

The priests and cantors elect their representatives on diocesan basis, using plurality election method. The laymen representatives are elected indirectly. The nominations for representatives are made by the parish councils which also elect the electors who then elect the lay representatives to the central synod. The central synod elects the bishops and is responsible for the economy and the general doctrine of the church.

The two executive bodies of the church central administration are the synod of bishops, responsible for the doctrinal and foreign affairs of the church, and the church administrative council (kirkollishallitus), responsible for day-to-day management of the church.

The parishes are governed by the rector and the parish council, which is elected in a secret election. All full-age members of the parish are eligible to vote and to be elected to the parish council. The members of the parish have the right to refrain from being elected to a position of trust of the parish only if they are over 60 years of age, or have served at least eight years in a position of trust. The parish council elects the parish board, which is responsible for the day-to-day affairs of the parish.

Financially, the church is independent of the state budget. The parishes are financed by the taxes paid by their members. The central administration is financed through the contributions of the parishes. The central synod decides yearly the amount of contributions the parishes are required to make.

The special status of the Orthodox church is most visible in the administrative processes. The church is required to conform with the general administrative law and the decisions of its bodies may be appealed against in the regional administrative courts. However, the court is limited to reviewing the formal legality of the decision. It may not overturn an ecclesiastical decision on the basis of its unreasonableness. The decisions of the synod of bishops and the central synod are not subject to the oversight of the administrative courts. In contrast, similar legal oversight of private religious communities is pursued by the district courts.

Finnish law protects the absolute priest–penitent privilege. A bishop, priest or deacon of the Church may not divulge information he has heard during confession or spiritual care. The identity of the sinner may not be revealed for any purpose. However, if the priest hears about a crime that is about to be committed, he is responsible for informing the authorities in such manner that privilege is not endangered.

Dioceses and bishops

Diocese of Karelia

The seat of the Archbishop of Karelia and All Finland is in Kuopio. The archbishop is the head of the church and the diocese. He is assisted in the diocese by a suffragan bishop known as the Bishop of Joensuu. Despite his title, the bishop is also seated at Kuopio. The word "Karelia" in the archbishop's title only refers to the Finnish Karelia.

The current Archbishop, Leo Makkonen, was born in 1948. Before his appointment as the archbishop in 2001, he was the Metropolitan of Helsinki from 1996, and Metropolitan of Oulu from 1980.[7] The current Bishop of Joensuu is Arseni, who took the position in 2005.[8]

The Diocese of Karelia has 22,000 church members in 12 parishes. The number of priests in the diocese is about 45, and churches and chapels total over 80. The diocese also includes the only orthodox monasteries in Finland.

The Orthodox Church Museum of Finland also operates in Kuopio.[9]

Diocese of Helsinki

Diocese of Helsinki has the most members, over 28,000. The diocese is divided into eight parishes, with 50 priests. The main church of the diocese is the Uspenski Cathedral in Helsinki. Characteristic to the diocese is the large number of members who have recently immigrated to Finland, especially in the Helsinki parish where several churches also officiate at the service in foreign languages, including Russian, English, Greek and Romanian.

The current bishop is the Metropolitan Ambrosius. He was appointed in 1988.[10]

Diocese of Oulu

The small Diocese of Oulu has only five parishes, the largest of which is Oulu. Traditionally, the Skolts, now a small minority of only 400 speakers, have been the earliest Orthodox Christians in the Finnish Lapland. Today, they live predominantly in the Inari parish.[11] The diocese was established in 1980. It has fewer than 10,000 members. The cathedral of the diocese is the Holy Trinity Cathedral of Oulu.

The head of the diocese since 1997 has been Metropolitan Panteleimon.[12] The head of the diocese since 2015 is Metropolitan Elia.

Monasteries

The only Orthodox Christian monastery in Finland, New Valamo (Valamon luostari), is situated in Heinävesi.[13] The only Orthodox Christian convent Lintula Holy Trinity Convent (Lintulan Pyhän Kolminaisuuden luostari) is in Palokki,[14] some 10 kilometers away from the monastery. Both were established during World War II when residents of the Karelian and Petsamo monasteries were evacuated from areas ceded to the Soviet Union. With friendly support from the Finnish Orthodox Church, a private Orthodox Brotherhood of Protection of the Mother of God (Pokrovan veljestö ry) has operated in Kirkkonummi since 2000, with two permanent members.[15][16]

Additional organizations

The following organizations operate within or on behalf of the Orthodox Church in Finland:

- Fellowship of St. Sergius and St. Herman (Pyhien Sergein ja Hermanin Veljeskunta)

- Orthodox Youth Association (Ortodoksisten nuorten liitto)

- Orthodox Student Association (Ortodoksinen opiskelijaliitto)

- Finnish Association of Orthodox Teachers (Suomen ortodoksisten opettajien liitto ry)[17]

- Orthodox Priests' Association (Ortodoksisten pappien liitto)

- Orthodox Cantors' Association (Ortodoksisten kanttorien liitto)

- Finnish Society of Icon Painters (Suomen ikonimaalarit ry)[18]

- Filantropia ry– Orthodox Church Aid and Foreign Mission society

Orthodox missions

The Finnish Orthodox Church established its own missionary organization in 1977 known as the Ortodoksinen Lähetys ry (Orthodox Missions). It has mainly been active in eastern Africa.[19] It later merged with OrtAid and formed Filantropia.

Feasts

The Finnish Orthodox Church (and, formerly, the Autonomous Estonian church) celebrates Easter according to the Gregorian calendar in order to comply with national legislation, which is unheard of elsewhere among the Eastern Orthodox jurisdictions. This has met with some disapproval among the Orthodox Churches elsewhere in the world.[20][21]

Church architecture

Many orthodox churches in Finland are small. The few more impressive shrines were built in the 19th century, when Finland was an autonomous Grand Duchy in the Russian Empire, with the Orthodox Christian Emperor as the Grand Duke of Finland. Notable churches in Helsinki from that era are the Uspenski Cathedral (1864) and the Holy Trinity Church (1826). The oldest Orthodox church in Finland is the Virgin Mary Church in Lappeenranta from 1782 - 1785.[22]

The sympathetic Orthodox Church of St. Peter and St. Paul in Hamina was completed in 1837. Built in the architectural style of Neoclassicism with some Byzantine-style elements, the exterior was designed in the form of a round-domed temple, while the interior is cruciform. The belfry was built in 1862 in the Neo-Byzantine style.

The Orthodox church of Tampere was built in Russian romantic style, with onion style cupolas, and was ready in 1896. The architect of the Russian army, T.U. Jasikov, drew the floor plan. The church was consecrated in 1899 to Saint Alexander Nevsky, a Novgorodian who in 1240 fought against the Catholic Swedes and two years later the Catholic Teutonic Knights with equal success. Emperor Nicholas II donated the bells to this church. The church suffered heavily during the Finnish civil war in 1918; its reconstruction took many years.[23] After Finland declared its independence, it was re-consecrated to St. Nicholas.

Construction of new Orthodox churches continues in Finland. One of the latest is the Church of Saint John the Theologian in Pori, completed in 2002.

History

Christianity started to spread to Finland from the east in the Orthodox form and from the west in the Catholic form at the latest in the beginning of the 12th century. Some of the earliest excavated crosses in Finland, dating from the 12th century onward, are similar to a type found in Novgorod and Kiev.[24] Orthodox parishes are believed to have existed as far to the west as Tavastia, the area inhabited by Tavastians in Central Finland.

Some core concepts of the Christian vocabulary in the Finnish language are supposed to be loans from early Russian, which in turn has borrowed them from Mediaeval Greek. These include the words for priest (pappi), cross (risti) and bible (raamattu). This hypothesis is, however, not unchallenged.[25]

Clash between Catholicism and Orthodoxy

In the middle of the 13th century the inevitable clash between the two expanding countries, Sweden and Novgorod, and the two forms of Christianity they represented, took place. The final border between western and eastern rulership was drawn in the Peace Treaty of Nöteborg, in 1323. Karelia was definitely ceded to Novgorod and Orthodoxy.[26]

Karelian monasteries

The main missionary work fell to the monasteries that cropped up in the wilderness of Karelia. Two monasteries were founded on islands in Lake Ladoga, which became some centuries later famous: the monasteries of Valaam (Finnish: Valamo) and Konevsky (Finnish: Konevitsa).

Karelian and Finnish forests were also populated by spiritually advanced hermits. Often around the hermit's hut or skete, there settled other fighters of the good fight of faith, and so a new monastery was founded. One of the most important examples of this process was St. Alexander of Svir (Finnish: Aleksanteri Syväriläinen) 1449–1533. He was a Karelian who fought the fight of faith for 13 years in Valaam monastery, but finally left it, and in the end founded a monastery at the river of Svir.[27]

Swedish oppression

The 17th century was a period of religious fanaticism and many religious wars as the newly emerged Protestant countries fought against countries that remained Catholic or Orthodox. At this time Sweden became a great force, expanding both southward and eastward. In Karelia the Swedish forces destroyed and burnt to the ground the monasteries of Valaam and Konevsky. Monks that did not flee, were killed. Many peasants met the same fate.

Karelians mostly identified themselves with the Russians, and not with the Finns.[28] Karelians rather called the Finns "ruotsalaiset," which is the Finnish word for Swedes.[29]

The Lutheran state church of Sweden tried to convert the Orthodox population. They were not allowed to obtain priests from Russia, which meant, in the long run, that they did not have priests at all. As Lutheranism was the only legal religion in Sweden, to be an Orthodox was a handicap in many ways. About two-thirds of the Orthodox population fled to Central Russia from under the oppression. They formed the population of Tver Karelia.[30] The Swedish state encouraged Lutheran Finns to occupy the deserted farms in Karelia. This massive flight of Orthodox Finns away from Finland meant that Eastern Orthodoxy was never again the main religion of any part of Finland. However, in the remoter areas of Eastern Finland and Karelia, like Ilomantsi, the Eastern Orthodox Christianity survived.[31]

Reunion with the Russian Orthodox Church

The period of the grandiose expansion of Sweden met its limits in two wars: the Great Northern War which ended in the Treaty of Nystad in 1721 and the Hat's War (1741–43) with the Treaty of Turku in 1743. Sweden lost all its provinces in the Baltic region, and a portion of eastern Finland to Russia.[32]

The Valaam Monastery was re-established in Lake Ladoga, and a new main church was consecrated in 1719. Monks returned to Konevsky Monastery before 1716.[33] The Russian government favoured the activities of the religion they had professed for many centuries. The Emperors and Empresses paid for the reconstruction of burnt or otherwise demolished churches. The Orthodox population of Eastern Finland again had access to making pilgrimages to the monasteries of Solovetsk and Alexander-Svirsky.[34]

The Old Believers, a schismatic group of Russians who did not accept the religious reforms of patriarch Nikon in 1666–67, were excommunicated from the Orthodox Church and fled to the outskirts of Russia. They also moved into the remote areas of Finland building three small monasteries there. However, the activity of these monasteries stopped during the following century.[33]

Autonomous Grand Duchy of Finland

When all of Finland became an autonomous Grand Duchy within the Russian Empire in 1809, it already had an established Lutheran Church. Eastern Orthodox Christianity also gained a recognized status in Finland. The old Swedish constitution which Finns generally regarded as the constitution of the Grand Duchy, specifically required that the sovereign was Protestant, but this was overlooked regarding the Orthodox Emperors.

When Russia at the end of the 19th century tried to retract the autonomy of Finland, the Lutheran Finns started to associate the Orthodox Church with the imperial Russian rule, labeled as the ryssän kirkko.[35] The cultural gap between the two churches remained significant.

In areas where Orthodox faith was not indigenous as in the towns of Helsinki, Tampere and Viipuri and the Karelian Isthmus, Orthodoxy was especially associated with the Russians, most of whom were Russian troops permanently stationed in Finland. Generally most ecclesiastical activity outside Karelia centered on the garrison churches. There were also a growing number of Russian emigrants, most of whom were merchants or craftsmen. These started to identify themselves with the Swedish-speaking bourgeoisie, and so a Swedish-speaking branch of the Finnish Orthodox Church was born.

The 19th century was also a period of active building of new churches, the Uspenski Cathedral being the most important of them. The garrisons needed Orthodox churches and so did the new emigrants to the towns. A good examples are the Orthodox church of Tampere and Turku.

In the rural countryside of Karelia, the local form of Orthodox faith remained somewhat primitive, incorporating many features of older religious praxis. Literacy among the Orthodox population was low. In 1900 it was estimated that of all persons over the age of 15 in East Finland, 32 percent were illiterate.[36] The Orthodox population knew very little of their faith except the outer forms. The priests were generally Russians who seldom knew Finnish. As Karelia and its arable land was poor, it did not attract first class priests. The language of the services was Church Slavonic, a form of old Bulgarian. A Russian could understand some parts of the services, a Finnish-speaking person nothing.[37]

A separate Finnish episcopate with a leading archbishop was established in 1892 under the Russian Orthodox Church. It was stationed in Vyborg, with the Russian Antoniy as its first bishop.

Independent Finland

Shortly after Finland declared independence from Russia in 1917, the Finnish Orthodox Church declared its autonomy from the Russian Church. Finland's first constitution (1919) granted the Orthodox Church an equal status with the (Lutheran) Church of Finland.[38]

In 1923, the Finnish Church completely separated from the Russian Church, becoming an autonomous church affiliated with the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople. At the same time the Gregorian Calendar was adopted. Other reforms introduced after independence include changing the language of the liturgy from Church Slavonic to Finnish and the transfer of the Archiepiscopal seat from Viipuri to Sortavala.

Until World War II, the majority of Orthodox Christians in Finland were located in Karelia. As a consequence of the war, residents of the areas ceded to the Soviet Union were evacuated to other parts of the country. The monastery of Valamo was evacuated in 1940 and the monastery of New Valamo was founded in 1941 at Heinävesi, on the Finnish side of the new border. Later, the monks from Konevsky and Petsamo monasteries also joined the New Valamo monastery. The nunnery of Lintula (now Ogonki) near Kivennapa (Karelian Isthmus) was also evacuated, and re-established at Heinävesi in 1946.

A new parish network was established, and many new churches were built in the 1950s. After the cities of Sortavala and Viipuri were lost to the Soviet Union (Viipuri is now Vyborg, Russia), the archiepiscopal seat was moved to Kuopio and the diocesan seat of Viipuri was moved to Helsinki. A third diocese was established in Oulu in 1979.

After the Second World War the membership of the Orthodox Church in Finland decreased slowly, as the Karelian evacuees were settled far from their roots among the Lutheran majority of Finland. Mixed marriages became common and the children were often baptized into the religion of the majority. But quite unexpectedly a "romantic" movement arose in Finland beginning in the 1970s onward glorifying Orthodoxy, its "mystical" and visually beautiful services and icons (religious paintings) and its deeper view of Christianity than that of the Lutheran Church. For these reasons, similar to Catholicism in England, conversion to the Orthodox Church became almost a fad, and its membership started to grow.

At the same time Archbishop Paavali of Karelia and All Finland (1960–1987) made liturgical changes to the services, that gave the laity a more active role in the church services, and made the services more open (earlier the clergy stayed behind a curtain for part of the services) and intelligible. Archbishop Paavali also stressed the importance of partaking in the Eucharist as often as possible.

In the 2010s, church membership has begun to decrease due to membership resignations and the declining number of baptisms. Compared to the membership trends of the Finnish Lutheran Church, members who resign from the Orthodox Church are on average slightly older and more likely to be female than those resigning from the Lutheran Church.[40]

Russian Orthodox Church in Finland

About 3,000 Orthodox Christians in Finland belong to the Russian Orthodox Church (Moscow Patriarchate). They are organized into two parishes.[41][42] There have also been plans to establish a separate Russian diocese in Finland.[43] Parishes maintain five churches and chapels.

St. Nicholas Orthodox Parish (Finnish: Ortodoksinen Pyhän Nikolauksen Seurakunta; Russian: Свято-Никольский приход в Хельсинки, Svjato-Nikol'skij prihod v Hel'sinki) in Helsinki is the largest with 2,600 members.[42] The parish was established in 1927, and a large part of its members are Finnish citizens. Recently, the parish has been growing fast due to a new wave of repatriates and immigrants from Russia.[44]

Rooted in the 1920s' Private Orthodox Society in Viipuri (Finnish: Yksityinen kreikkalais-katolinen yhdyskunta Viipurissa), the Intercession Orthodox Parish (Finnish: Ortodoksinen Pokrovan seurakunta; Russian: приход Покрова Пресвятой Богородицы в Хельсинки, prihod Pokrova Presvjatoj Bogorodicy v Hel'sinki) was officially formed in 2004,[45] also in Helsinki, and has some 350 members today. Both have registered themselves as separate religious organizations.[46]

Unlike the Finnish Orthodox Church, the Russian Orthodox Church in Finland follows the Julian calendar.

List of archbishops

Under Patriarchate of Moscow:[47]

- Antoniy (1892–1898)

- Nikolay (1899–1905)

- Sergiy (1905–1917)

- Serafim (1918–1923), Bishop of Finland from 1918 and archbishop from 1921

Under Patriarchate of Constantinople:

- Herman (1923–1960)

- Paavali ("Paul") (1960–1987)

- Johannes ("John") (1987–2001)

- Leo (2001-)

Further reading

- Arvola, Pekka; Kallonen, Tuomas, eds (2010) (in english). 12 ikkunaa ortodoksisuuteen Suomessa. Helsinki: Maahenki & Ortodoksisen kirjallisuuden julkaisuneuvosto. ISBN 978-952-5870-16-9.

- Purmonen, Veikko, ed (1984). Orthodoxy in Finland : past and present (2. rev. and enl. ed.). Kuopio: Orthodox Clergy Association. ISBN 951-95582-2-5.

References

- ↑ Official site of the Finnish Orthodox Church .

- ↑ The whole section is based on Law on the Finnish Orthodox Church.

- ↑ The official text of the Treaty of Tomos between the Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Finnish Orthodox Church in 1923.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namednumber_of_orthodox - ↑ Helsingin Sanomat 7.8.2005 (in Finnish) cited 24-11-2006

- ↑ Evankelis-luterilaisen kirkon nelivuotiskertomus (Finnish Evangelic-Lutheran Church: Quadriannual report) 1996–1999 Cited 24-11-2006 (in Finnish)

- ↑ Archbishop Leo's home page .

- ↑ Bishop Arseni's home page .

- ↑ "Ortodoksinen kirkkomuseo". Suomen ortodoksinen kirkko. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150403172810/http://www.ort.fi/kirkkomuseo. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Metropolitan Ambrosius' home page .

- ↑ Hämynen, Tapio: Ryssänkirkkolaisia vai aitoja suomalaisia? Ortodoksit itsenäisessä Suomessa Cited 24-11-2006 (in Finnish).

- ↑ Metropolitan Panteleimon's home page .

- ↑ New Valamo home page .

- ↑ Lintula Holy Trinity Convent .

- ↑ Official site of Pokrova.

- ↑ "Ortodoksi.net - Pokrovan yhteisö". Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. https://web.archive.org/web/20150924062518/http://www.ortodoksi.net/tietopankki/luostarit/pokrovan_yhteiso.htm. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Finnish Association of Orthodox Teachers' official site.

- ↑ Finnish Society of Icon Painters' official site .

- ↑ Orthodox Missions .

- ↑ Sanidopoulos, J. (12 June 2013) The Date of Orthodox Easter in Finland, Mystagogy Resource Center, Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ↑ Fr. Andrew Stephen Damick (31 March 2015) No, Pascha does not have to be after Passover (and other Orthodox urban legends), Ancient Faith Ministries, Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ↑ www3.lappeenranta.fi

- ↑ Fr. Ambrosius and Markku Haapio: Ortodoksinen kirkko Suomessa (1979) p.496-497

- ↑ "*Holdings: Ikkunoita Bysanttiin". http://herkules.oulu.fi/isbn9514270606/html/a3.html. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ Virrankoski, P.: "Suomen historia I" (2002) p.58

- ↑ "Orthodoxy in Finland, past and present", edited by V. Purmonen (1984)p. 14-15

- ↑ E.Piiroinen: "Karjalan pyhät kilvoittelijat"("The holy fighters of faith in Karelia") (1979) p.25-31

- ↑ Hämynen, Tapio: "Suomalaistajat, venäläistäjät ja rajakarjalaiset" (1995) pp. 34–5.

- ↑ Hämynen, Tapio: Suomalaistajat, venäläistäjät ja rajakarjalaiset" (1995), pp. 37–8.

- ↑ The Karelian language and customs were preserved there until the beginning of the 20th century. Many Finnish anthropologists in the 19th century visited Tver Karelia in order to collect samples of old Karelian traditions and language.

- ↑ "Ortodoksinen Kirkko Suomessa", ed. by Fr. Ambrosius and M. Haapio (1979), pp. 107–13.

- ↑ Virrankoski, Pentti: "Suomen historia I" (2002), pp. 286, 295.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Virrankoski, P.: "Suomen historia I" (2002), p. 356.

- ↑ "Ortodoksinen kirkko Suomessa" ed. by Fr. Ambrosius and M. Haapio (1979), p. 116.

- ↑ "Ryssä" is a pejorative name for Russians in Finnish.

- ↑ "Ortodoksinen kirkko Suomessa" ed. by Fr. Ambrosius and M. Haapio (1979) p. 122-124

- ↑ Hämynen, T.:"Suomalaistajat, venäläistäjät ja rajakarjalaiset" (1995) p.49.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-06-25. https://web.archive.org/web/20060625120307/http://www.minedu.fi/julkaisut/hallinto/2004/tr32/tr32.pdf. Retrieved 2006-01-17.

- ↑ History of the Suomenlinna church by the Governing Body of Suomenlinna.

- ↑ Eroakirkosta.fi - Ortodoksisesta kirkosta erottiin vilkkaasti

- ↑ Official site of the Russian Orthodox Church in Finland.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Ortodoksinen Pyhän Nikolauksen Seurakunta Uskonnot Suomessa (combined statistics of two parishes for 2013)

- ↑ Räntilä, Kari, M: Uusia linjauksia kirkkomme idänsuhteissa?Analogi 5/2004., 2004. See also Helsingin Sanomat, December 15, 2006.

- ↑ Official site of the St. Nicholas Orthodox Parish in Helsinki.

- ↑ "FINLEX ® - Säädökset alkuperäisinä: 820/2004". http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2004/20040820. Retrieved 5 March 2015.

- ↑ http://www.vaestorekisterikeskus.fi/vrk/files.nsf/files/8C40FF333A489025C22571A4004B1DB4/$file/rekuskonnolliset_yhd_vrk31122005.htm

- ↑ Russian archbishops .

External links

- The Orthodox Church of Finland (Official site)

- New Valamo Monastery in Finland

- OrtoWeb (Learning Environment for R.E)

- Ortodoksi.net (in English)

- Article on Finnish Orthodox Church by Ronald Roberson on the CNEWA website